Allen County Museum

Allen County Museum Original Entrance

Allen County Museum's New Entrance

These dueling pistols are replicas of ones owned by George Washington. The originals were made in London by Wilson & Hawkins, and the replicas made by the Belgian firm Centaure.

This horse-drawn hearse was used by the undertaker Charles B. Miller in Spencerville, Ohio.

Spartacus by Fortunato Galli

This portrait of Calvin Brice was painted by John Singer Sargent in 1898.

John Dillinger in Lima County Jail

This horse-drawn wagon was used up until the 1960s.

Thor Motorcycle

Car 60 ran on the Lima City Street Car Company until 1939.

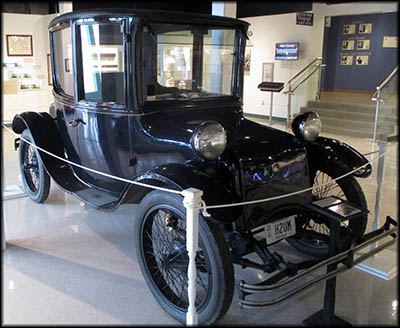

1923 Milburn Electric Car

Lima Canteen

This Westinghouse neon sign was made by the Artkraft in 1946 and remained stored in a crate until 1992 when it was donated to the Allen County Museum.

The museum has a set of model houses.

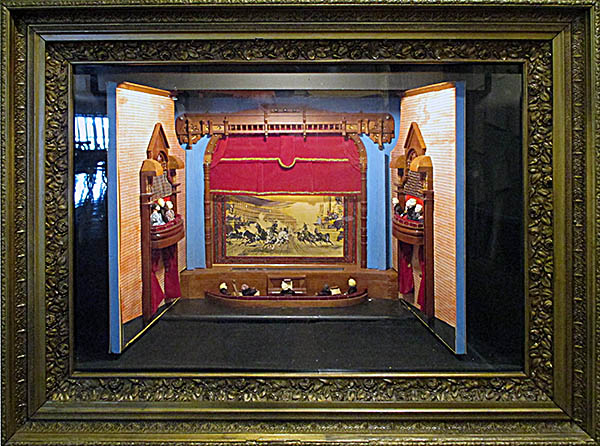

Diormama of the Faurot Opera House

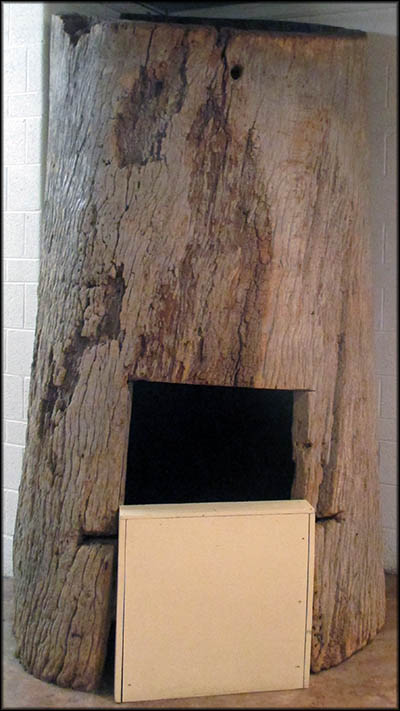

The hollowed out gum tree trunk was used for many years as the Goodwin family's smokehouse. In its later years, it was made into a playhouse.

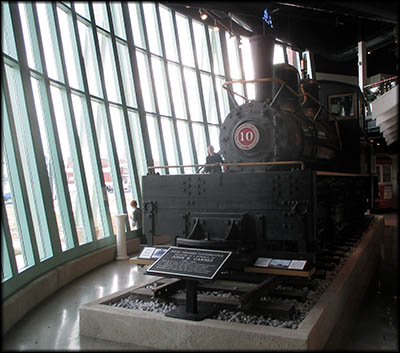

Shay Engine 3288

Those travelling through the entirety of Northwest Ohio along Interstate 75 will at one point pass through Allen County, which offers an unimpressive view of flat, field-covered lands dotted by two cities and seven villages that reveals nothing about the county’s rich history. When pioneers first settled here after displacing the Shawnee people, the area was covered with thick forest. Since that moment, many remarkable things have happened here. In 1933, for example, John Dillinger was held in a jail in Lima from which his gang broke him out, killing the county sheriff, Jess Sarber, in the process.

A good place to learn about the county’s history is the Allen County Museum in Lima. It’s jam-packed with historic artifacts and the sort of art you’d expect to see at a major metropolitan art museum. One impressive piece, as an example, is a sculpture of Spartacus, the gladiator who unsuccessfully led a rebellion against the Roman Empire and inspired the movie of the same name. The museum’s information sign about this work contained nothing more than names of the sculpture and its artist, Fortunato Galli. An online search yielded little about Galli save that he was born in Italy in 1850, worked in Florence, and died in 1918. One of his pieces, the Nymph, sold for $247,046 at Sotheby’s in 2019.

A number of rare vehicles can also be found in the museum, including two horse-drawn hearses of exceptional beauty and craftsmanship, a horse-drawn Meadow Gold milk wagon, and a Thor motorcycle. This racing bike, few of which exist today, was produced by the Aurora Machine and Tool Company in Aurora, Illinois. Between 1902 to 1907, Aurora Machine was contracted by Indian Motorcycle to produce some of the parts it used for its motorcycles. After the contract ended, Aurora Machine began making its own motorcycle, the Thor. Although the Thor was never a racing powerhouse like Harleys and Indians, it did set some speed records on dirt tracks. Aurora Machine discontinued making the Thor around 1916, turning instead to the production of appliances.

The Thor in the museum was bought second-hand for $100 in 1915 from the Gladwell-Crossing Motor Company in Lima by Ralph Marshall. In addition to racing his new motorcycle locally, Marshall was also a sharpshooter and sportsman. He qualified for the 1936 Olympics’ free pistol shooting event but won no medals.

A good place to learn about the county’s history is the Allen County Museum in Lima. It’s jam-packed with historic artifacts and the sort of art you’d expect to see at a major metropolitan art museum. One impressive piece, as an example, is a sculpture of Spartacus, the gladiator who unsuccessfully led a rebellion against the Roman Empire and inspired the movie of the same name. The museum’s information sign about this work contained nothing more than names of the sculpture and its artist, Fortunato Galli. An online search yielded little about Galli save that he was born in Italy in 1850, worked in Florence, and died in 1918. One of his pieces, the Nymph, sold for $247,046 at Sotheby’s in 2019.

A number of rare vehicles can also be found in the museum, including two horse-drawn hearses of exceptional beauty and craftsmanship, a horse-drawn Meadow Gold milk wagon, and a Thor motorcycle. This racing bike, few of which exist today, was produced by the Aurora Machine and Tool Company in Aurora, Illinois. Between 1902 to 1907, Aurora Machine was contracted by Indian Motorcycle to produce some of the parts it used for its motorcycles. After the contract ended, Aurora Machine began making its own motorcycle, the Thor. Although the Thor was never a racing powerhouse like Harleys and Indians, it did set some speed records on dirt tracks. Aurora Machine discontinued making the Thor around 1916, turning instead to the production of appliances.

The Thor in the museum was bought second-hand for $100 in 1915 from the Gladwell-Crossing Motor Company in Lima by Ralph Marshall. In addition to racing his new motorcycle locally, Marshall was also a sharpshooter and sportsman. He qualified for the 1936 Olympics’ free pistol shooting event but won no medals.

Not too far from where the Thor resides, visitors will see in the museum’s main stairway to its lower level a portrait of Calvin Brice painted by John Singer Sargent. Sargent is possibly America’s most accomplished portrait artist of the nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries. Not that he was all that American. Although his parents were from Philadelphia, he was born in Italy in 1856, raised in Europe, and he didn’t set foot in the United States until 1876. With such an upbringing, it ought not be a surprise that beyond English, he also spoke fluent French and Italian.

He considered his greatest work to be a portrait of Madame Pierre Gautreau, which he submitted to the Parisian salon in 1884. To his horror, it was considered scandalous because the woman in question looked sexy, had one of her dress straps falling off her shoulder and she was married woman. He later repainted the strap so it went over her shoulder. So shocking was it, when he sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, he insisted it be titled Madam X to keep his subject’s identity secret. Later in life, Sargant gave up portraiture work and changed to painting watercolors and murals.

In 1898 he painted a portrait of Senator Calvin Brice, who was born in Ohio’s Morrow County on September 17, 1845. At the age of thirteen, Brice started attending a preparatory school at Miami University. When the Civil War broke out, he tried to join the Union Army but was rejected for being too young. The next year he enlisted again. Accepted, he served in West Virginia guarding railroads. After three months, he returned to and finished school, taught a public school in Lima, and served as a clerk in the Allen County Auditor’s office. Joining Union Army once more, this time he was assigned to guard railroads in Tennessee and North Carolina.

He considered his greatest work to be a portrait of Madame Pierre Gautreau, which he submitted to the Parisian salon in 1884. To his horror, it was considered scandalous because the woman in question looked sexy, had one of her dress straps falling off her shoulder and she was married woman. He later repainted the strap so it went over her shoulder. So shocking was it, when he sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, he insisted it be titled Madam X to keep his subject’s identity secret. Later in life, Sargant gave up portraiture work and changed to painting watercolors and murals.

In 1898 he painted a portrait of Senator Calvin Brice, who was born in Ohio’s Morrow County on September 17, 1845. At the age of thirteen, Brice started attending a preparatory school at Miami University. When the Civil War broke out, he tried to join the Union Army but was rejected for being too young. The next year he enlisted again. Accepted, he served in West Virginia guarding railroads. After three months, he returned to and finished school, taught a public school in Lima, and served as a clerk in the Allen County Auditor’s office. Joining Union Army once more, this time he was assigned to guard railroads in Tennessee and North Carolina.

After the war, he studied law at the University of Michigan, and the next year he was admitted to the bar. In 1868, he returned to Lima where he became a partner with fellow lawyer James Irvin. He found success working for the Lake Erie & Western Railroad’s legal department, a company he would one day run as its president. Over his lifetime he involved himself in other railroads, banking, and gas companies. Known as a railroad tycoon, he facilitated the organization of the Nickel Plate Railroad, which he then arranged to sell to William Vanderbilt three days after it was incorporated. Active in Democratic politics, he became a U.S. senator for Ohio in 1890. His political career didn’t have much time to mature beyond that. He died of pneumonia in 1898, aged fifty-three.

That Brice got involved in railroad business isn’t a surprise. At the time, five different railroads had lines running through Lima. Complementing these railroads was Lima Machine Works, a company that built steam locomotives. Its biggest sellers were the Shay and superpower A-1 engines. The Shay was created to pull exceptionally heavy weights and sold mainly to logging operations and mines. It was invented by Ephraim Shay, a lumberman in Michigan who’d previously engaged Lima Machine to make saws. He asked the company to help him improve his prototype engine. It built its first Shaw in 1880. Ephraim gave Lima Machine the right to use his patent, which it improved upon, making it the exclusive producer of Shay locomotives.

That Brice got involved in railroad business isn’t a surprise. At the time, five different railroads had lines running through Lima. Complementing these railroads was Lima Machine Works, a company that built steam locomotives. Its biggest sellers were the Shay and superpower A-1 engines. The Shay was created to pull exceptionally heavy weights and sold mainly to logging operations and mines. It was invented by Ephraim Shay, a lumberman in Michigan who’d previously engaged Lima Machine to make saws. He asked the company to help him improve his prototype engine. It built its first Shaw in 1880. Ephraim gave Lima Machine the right to use his patent, which it improved upon, making it the exclusive producer of Shay locomotives.

Railroads were exceptionally important during World War II because they were the primary means of moving American soldiers. With so many GIs throughout the United States on rails, the American Women’s Voluntary Services (AVWS) decided to build canteens across the United States to feed them. One was constructed in Lima in 1942 along the Pennsylvania Railroad’s tracks near where they intersected with the Baltimore & Ohio’s. All year round volunteers staffed it, distributing free food to the soldiers passing through. All food came from donations. In Lima alone, farmers, bakeries, grocery stores and others donated about 500,000 pounds of food, this feeding men from about 30,000 passing trains. Most of the AWVS canteens closed when the war ended, but Lima’s remained open until 1970. It can be seen in the museum complete with photos of World War II veterans hanging on strings. One museum volunteer showed me pictures of her own father. He had served in the supply department at Las Alamos.

Complementing Lima’s railroads was an electric trolley system, the first of its kind in Ohio and only the second in the United States. Called the Lima City Street Car Company, it served the city until 1939 at which point a bus route replaced it. After the system’s breakup, one of its trolleys, Car 60, was sold to farmer in Ohio’s Hancock County. Left to decay, its cabin was rescued and restored by the Allen County Historical Society in 1962 and is now in the museum. Car 60 ran in Lima from until 1939. In the museum, one of the placards on its front is for a baseball game once played in Lima that included Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth.

Near the trolley cab is a 1923 electric car manufactured by the Milburn Wagon Company in Toledo, Ohio. One of the lesser-known facts about electric cars is that they were not only sold in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, they successfully competed with those powered by steam or the internal combustion engine. Electric vehicles were preferred in cities because they were relatively quiet and provided a smooth ride. Cars with internal combustion engines, in contrast, were noisy, smelled, dangerous to start, and prone to breakdowns.

Cars using internal combustion engines needed gas, a commodity Allen County had in abundance thanks to an unexpected discovery in 1885. While drilling for water and gas bear his Lima factory, Benjamin Faurot hit oil instead. This was the first well drilled in became know as the Lima Oil Field, which covered most of Northwest Ohio and part of Indiana. At the time it was the largest oil field in the world. Oil made Faurot wealthy, allowing him to build an opera house named after himself. His venue hosted Vaudeville acts, plays, and movies until 1934 when it shut down.

Complementing Lima’s railroads was an electric trolley system, the first of its kind in Ohio and only the second in the United States. Called the Lima City Street Car Company, it served the city until 1939 at which point a bus route replaced it. After the system’s breakup, one of its trolleys, Car 60, was sold to farmer in Ohio’s Hancock County. Left to decay, its cabin was rescued and restored by the Allen County Historical Society in 1962 and is now in the museum. Car 60 ran in Lima from until 1939. In the museum, one of the placards on its front is for a baseball game once played in Lima that included Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth.

Near the trolley cab is a 1923 electric car manufactured by the Milburn Wagon Company in Toledo, Ohio. One of the lesser-known facts about electric cars is that they were not only sold in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, they successfully competed with those powered by steam or the internal combustion engine. Electric vehicles were preferred in cities because they were relatively quiet and provided a smooth ride. Cars with internal combustion engines, in contrast, were noisy, smelled, dangerous to start, and prone to breakdowns.

Cars using internal combustion engines needed gas, a commodity Allen County had in abundance thanks to an unexpected discovery in 1885. While drilling for water and gas bear his Lima factory, Benjamin Faurot hit oil instead. This was the first well drilled in became know as the Lima Oil Field, which covered most of Northwest Ohio and part of Indiana. At the time it was the largest oil field in the world. Oil made Faurot wealthy, allowing him to build an opera house named after himself. His venue hosted Vaudeville acts, plays, and movies until 1934 when it shut down.

The oil boom caused Lima’s population to double from 8,000 to 16,000 in just a decade and created many jobs, though not all of them were good ones. Those who worked in the oil fields, for example, faced many dangers. One job in particular, the shooter or go-devil, was especially hazardous to one’s health. The shooter dropped a torpedo tipped with nitroglycerin into a drill hole, then had to “go like the devil” to get out of the way before it exploded. And with nitroglycerin being an unstable substance that has a habit of prematurely exploding, many shooters were killed or maimed by when it went off unexpectedly.

The crude pumped out of the Lima field was sour—that is, it had a lot of sulphur in it, making it undesirable as lighting oil because of the smell it produced. Fortunately, German chemist Carl Friedrich Claus had patented a refinery process to remove the sulphur two years before the discovery of the Lima field. It was adopted by Standard Oil, which bought all the wells in the Lima Oil Field, giving the company a monopoly. In 1888, John Wesley Van Dyke was tasked by Standard Oil to build a refinery on J.A. Hoover’s farm in Allen County. Called the Solar Refinery, it operates to this day and mainly produces gasoline.

While Allen County’s oil boom lasted about ten years, unrelated industries also started here including ones that made neon signs. The first two neon signs displayed in the United States appeared at a Los Angels Packard car dealership in 1923. They were bought from a company started by Frenchman Georges Claude, the man who’d discovered applying electricity to neon caused it to glow. He put it into a glass tube and displayed it at the 1910 Paris Art Show. After this, he realized that by bending the glass into shapes, he could make glowing signs.

The crude pumped out of the Lima field was sour—that is, it had a lot of sulphur in it, making it undesirable as lighting oil because of the smell it produced. Fortunately, German chemist Carl Friedrich Claus had patented a refinery process to remove the sulphur two years before the discovery of the Lima field. It was adopted by Standard Oil, which bought all the wells in the Lima Oil Field, giving the company a monopoly. In 1888, John Wesley Van Dyke was tasked by Standard Oil to build a refinery on J.A. Hoover’s farm in Allen County. Called the Solar Refinery, it operates to this day and mainly produces gasoline.

While Allen County’s oil boom lasted about ten years, unrelated industries also started here including ones that made neon signs. The first two neon signs displayed in the United States appeared at a Los Angels Packard car dealership in 1923. They were bought from a company started by Frenchman Georges Claude, the man who’d discovered applying electricity to neon caused it to glow. He put it into a glass tube and displayed it at the 1910 Paris Art Show. After this, he realized that by bending the glass into shapes, he could make glowing signs.

The first company to these in Lima was Artkraft Sign, which was started in 1921 with just three people. At first it made appliance housing and electric signs, then it franchised with Claude’s company and turned to making neon signs. Despite the Great Depression, by 1937 it was once of the largest producers of neon signs in America with 200 employees. During World War II, it stopped making signs so it could produce fluorescent light bulbs for the military. During this time it had 425 employees. After the war, it began making appliances, and in the early 1950s, it merged with Baltimore’s Universal Major Electric Appliance.

It didn’t entirely abandon producing neon signs. In 1946 it made one for a Westinghouse retail store in Logan, Utah. When Westinghouse cancelled the store’s opening because a small businessman across the street complained he already sold its products, the sign was given to an appliance dealer in Lima. He didn’t have room to display it, so it remained in a crate for forty-six years until the dealer’s grandson found and donated it to the Allen County Museum in 1992. Lima’s Artkraft plant closed in 1953.

Two of Artkraft’s employees, James Howenstine and Sam Kamin, left in 1930 to start their own company with less than $500. Called Neon Products, it made neon clocks and window signs. When Prohibition ended, demand by beer makers for neon signs spiked, but in 1935 Ohio’s liquor control commission ruled that retailers couldn’t use trade name signs. This upset Neon Sign, which claimed the rule had reduced its potential output by twenty-five percent that year. During World War II, Neon Products made electric harnesses for B-24 Liberator bombers. Impressed by Plexiglass, in 1949 it started making neon and fluoride signs out of plastic. Essex International bought the Neon plant in 1969, then sold it to the General Indicator Corporation in 1975. The plant closed in 1977. Signs from both Neon Products and Artkraft are on display in the museum.🕜

It didn’t entirely abandon producing neon signs. In 1946 it made one for a Westinghouse retail store in Logan, Utah. When Westinghouse cancelled the store’s opening because a small businessman across the street complained he already sold its products, the sign was given to an appliance dealer in Lima. He didn’t have room to display it, so it remained in a crate for forty-six years until the dealer’s grandson found and donated it to the Allen County Museum in 1992. Lima’s Artkraft plant closed in 1953.

Two of Artkraft’s employees, James Howenstine and Sam Kamin, left in 1930 to start their own company with less than $500. Called Neon Products, it made neon clocks and window signs. When Prohibition ended, demand by beer makers for neon signs spiked, but in 1935 Ohio’s liquor control commission ruled that retailers couldn’t use trade name signs. This upset Neon Sign, which claimed the rule had reduced its potential output by twenty-five percent that year. During World War II, Neon Products made electric harnesses for B-24 Liberator bombers. Impressed by Plexiglass, in 1949 it started making neon and fluoride signs out of plastic. Essex International bought the Neon plant in 1969, then sold it to the General Indicator Corporation in 1975. The plant closed in 1977. Signs from both Neon Products and Artkraft are on display in the museum.🕜

Swiss Music Box

Pioneer Kitchen