Belgium

Ieper (Ypres)

Ieper’s Cathedral

St. Symphorien Military Cemetery in Hainaut

Construction workers uncovered this live mortar shell near one of the WWI sites my tour group was visiting while we there.

This is only one of three monuments to the German dead erected by the Germans in Belgium. Our tour guide, Marc Hope, helped in the effort to find this German cemetery several years ago.

To get to Belgium we started in a small, dumpy café near a Tube station in the London borough of Hounslow. Having learned the hard way that you have to double the time you think you need to get anywhere in the city, we arrived nearly two hours early. With rain threatening and nowhere to sit, we decided to reside in the café until our coach arrived. To justify this, I bought some hot chocolate and a croissant for breakfast, then explained to the woman serving me our plan to stay until our coach arrived. She shrugged her shoulders and said she didn’t speak English.

As we sat there, paranoia ate at me. What if we had the wrong place? What if we got kicked out and had to stand outside in the rain? What if we somehow missed the coach? With no cell phone (neither of ours worked in Europe) and not a phone booth in sight, getting hold of the tour company might prove a bit difficult. Welling in my underlining fears, I waited. Finally the coach arrived and off we went.

As we sat there, paranoia ate at me. What if we had the wrong place? What if we got kicked out and had to stand outside in the rain? What if we somehow missed the coach? With no cell phone (neither of ours worked in Europe) and not a phone booth in sight, getting hold of the tour company might prove a bit difficult. Welling in my underlining fears, I waited. Finally the coach arrived and off we went.

I had begun planning this trip in the summer of 2014 when I decided it would be nice to do some onsite research for the book I was working on at the time about the First World War. I initially thought I’d fly directly to Belgium and there either rent a car or use mass transport to get around. I quickly scrapped that idea because I didn’t want to go wandering around in a foreign country in which I don’t speak either of its official languages, Flemish (a form of Dutch) and French (spoken by the Walloon population). No, what I wanted was a tour in English, so I went online and found one called “The Old Contemptibles” by Leger Holidays of Britain. This tour explored World War I in 1914, the year I was interested in, and would go to many of the places I wished to visit.

I asked my mother to be my traveling companion for the trip to which she happily agreed. While Leger would get us from London to Belgium, it wouldn’t handle the portion of the trip from America to the UK. For this part we used an online travel service, and while planning it, my mom suggested that since we were going to London anyway, we ought to head there early so we could see the city for a couple of days. This we did, and for those interested in reading about that portion of trip, click here.

We would reach Europe by catching a ferry in Dover bound for Calais, France. Once on the ferry, we decided to watch our departure from the outdoor observation deck. A few minutes out at sea, I realized my jacket wasn’t keeping me warm enough, so we went below and headed for the ferry’s giftshop in which I hoped to purchase a sweatshirt. This being an English ferry, I found aisles and aisles of sweets (the British do love their candy), but little in the way of apparel. The only sweatshirt I found had on it “I Love London.” And while I’d normally never wear anything says something like this, necessity trumped taste and I bought it. My only consolation was that I at least had a jacket over it and therefore no one could see what it said.

Once in France we headed for Belgium and, because both countries belong to the European Union, no border crossing impeded us. For the duration of the trip we would stay in the excellent Novotel Hotel in Ieper, or Ypres. (Pronouncing this city’s name turned out to be trickier than one might think. The English pronounce it as “Eep,” which rhymes with “jeep”. Its own inhabitants call it “Ee-pier” while the French-speakers say, “Ee-pra.”) Although Ieper looks like a beautiful Medieval town complete with cobblestone streets surrounded by a wall and wide moat, in truth none of its buildings date any earlier than 1919 because the Germans flattened the place during the First World War, with some ruins remaining to this day. World War I’s dead have left Ieper with far more graveyards than a city with a population of about 35,000 would otherwise need, nearly all of them military.

I asked my mother to be my traveling companion for the trip to which she happily agreed. While Leger would get us from London to Belgium, it wouldn’t handle the portion of the trip from America to the UK. For this part we used an online travel service, and while planning it, my mom suggested that since we were going to London anyway, we ought to head there early so we could see the city for a couple of days. This we did, and for those interested in reading about that portion of trip, click here.

We would reach Europe by catching a ferry in Dover bound for Calais, France. Once on the ferry, we decided to watch our departure from the outdoor observation deck. A few minutes out at sea, I realized my jacket wasn’t keeping me warm enough, so we went below and headed for the ferry’s giftshop in which I hoped to purchase a sweatshirt. This being an English ferry, I found aisles and aisles of sweets (the British do love their candy), but little in the way of apparel. The only sweatshirt I found had on it “I Love London.” And while I’d normally never wear anything says something like this, necessity trumped taste and I bought it. My only consolation was that I at least had a jacket over it and therefore no one could see what it said.

Once in France we headed for Belgium and, because both countries belong to the European Union, no border crossing impeded us. For the duration of the trip we would stay in the excellent Novotel Hotel in Ieper, or Ypres. (Pronouncing this city’s name turned out to be trickier than one might think. The English pronounce it as “Eep,” which rhymes with “jeep”. Its own inhabitants call it “Ee-pier” while the French-speakers say, “Ee-pra.”) Although Ieper looks like a beautiful Medieval town complete with cobblestone streets surrounded by a wall and wide moat, in truth none of its buildings date any earlier than 1919 because the Germans flattened the place during the First World War, with some ruins remaining to this day. World War I’s dead have left Ieper with far more graveyards than a city with a population of about 35,000 would otherwise need, nearly all of them military.

Hooge Crater has a recreated trench, an authentic pillbox, a café in which we ate lunch, and an excellent museum that contains many artifacts from the war including a wide variety of artillery and mortar shells. Here, too, is a graveyard in which many British Commonwealth are buried. As I wandered in and around the trench system and pillbox, something odd caught my eye. Within a fenced-in field was a strange-looking animal that looked like a deer. Earlier in the day I thought I’d seen a deer within a fence elsewhere but figured I’d been mistaken. Since I couldn’t get that close to this mystery animal, I snapped some photos using my camera’s excellent zoom. Because the sun prevented me from seeing its screen, I didn’t have a chance to look at it until I was back in the coach.

It was indeed a deer. I asked our guide if the Belgians keep deer as pets. He explained that Belgians living in rural areas such as this get a tax break if their house is part of a farm. Many of those living in the country don’t have a working farm per se, but so long as they keep certain kinds of animals on the premises, their place qualifies as such, and deer fall into this category.

At the town of Mesen (Messines), the site of another of the battles between the British and Germans, we visited an excellent little museum. We also stopped at a church with a crypt the Germans used as an aid station in which Corporal Adolf Hitler once received medical treatment. Here, too, is a tomb containing William the Conqueror’s mother-in-law, Saint Adèla, Countess of Flanders, whom William hadn’t especially liked and thought she was best left here rather than being brought to England for her eternal rest.

So far we’d look primarily at the actions of the British Expeditionary Force, but the Belgians hadn’t stood idle while the Germans invaded. To keep these intruders from easily passing in the north, the Belgian army decided to open up the canal lock gates in the city of Nieuwpoort to flood the area to the south. This they did on October 25, 1914, and it worked better than they could have hoped. The major detour it forced the German army to take slowed its timetable enough that it failed to take Paris as planned.

Soon enough the Germans headed back to Nieuwpoort in an effort to outflank the Allies, who did likewise. This "Race to the Sea” ended at the North Sea, making the city the northernmost point of the trench system that extended all the way south to the Swiss border. Upon arriving in the city, we stopped at the new visitor center, a place capped with a massive monument to King Albert I, Belgian’s ruler during the war. With our time short and the cost of going through the museum something like €7, no one in our group paid to get in, meaning that none of us could take the elevator to the monument’s top to get a good view of the city.

Left on our own soon after, my mother and I decided to look at the monument marking the northern end of war’s trench system. At first I mistook it for something else because it said, “Touring Club of France.” It wasn’t until I looked on its other side that I found information about the spot’s importance. The Touring Club had sponsored the monument’s construction.

It was indeed a deer. I asked our guide if the Belgians keep deer as pets. He explained that Belgians living in rural areas such as this get a tax break if their house is part of a farm. Many of those living in the country don’t have a working farm per se, but so long as they keep certain kinds of animals on the premises, their place qualifies as such, and deer fall into this category.

At the town of Mesen (Messines), the site of another of the battles between the British and Germans, we visited an excellent little museum. We also stopped at a church with a crypt the Germans used as an aid station in which Corporal Adolf Hitler once received medical treatment. Here, too, is a tomb containing William the Conqueror’s mother-in-law, Saint Adèla, Countess of Flanders, whom William hadn’t especially liked and thought she was best left here rather than being brought to England for her eternal rest.

So far we’d look primarily at the actions of the British Expeditionary Force, but the Belgians hadn’t stood idle while the Germans invaded. To keep these intruders from easily passing in the north, the Belgian army decided to open up the canal lock gates in the city of Nieuwpoort to flood the area to the south. This they did on October 25, 1914, and it worked better than they could have hoped. The major detour it forced the German army to take slowed its timetable enough that it failed to take Paris as planned.

Soon enough the Germans headed back to Nieuwpoort in an effort to outflank the Allies, who did likewise. This "Race to the Sea” ended at the North Sea, making the city the northernmost point of the trench system that extended all the way south to the Swiss border. Upon arriving in the city, we stopped at the new visitor center, a place capped with a massive monument to King Albert I, Belgian’s ruler during the war. With our time short and the cost of going through the museum something like €7, no one in our group paid to get in, meaning that none of us could take the elevator to the monument’s top to get a good view of the city.

Left on our own soon after, my mother and I decided to look at the monument marking the northern end of war’s trench system. At first I mistook it for something else because it said, “Touring Club of France.” It wasn’t until I looked on its other side that I found information about the spot’s importance. The Touring Club had sponsored the monument’s construction.

Nieuwpoort Locks

Much to the distress of the people of Antwerp, nineteenth century Belgium’s leadership decided to make the city the “National Reduit,” the place where the government and army would fall back in case an invading force could not be stopped. To defend the city, the Belgian army build a series of fortresses, which were periodically upgraded over the years to defend against new types of weapons. Several of these forts still stand, Fort Liezele among them.

Although all its original artillery pieces and other weapons were removed long ago, the rest of the structure remains intact. Among other places, we climbed to its top, entered a gas-proof room, and visited an entry bridge that, when retracted, reveals a deep, water-filled pit. In the room where the main gun once stood, I asked if those firing it had needed ear protection, or if anyone at time even thought that necessary. Our fortress guide informed me that sound went right out through the same ventilation system that kept the air fresh, so those firing the gun were spared the loud booms it made.

Because the fort is in part privately funded, the group that operates it, Stitching Fort Liezele vzw, has to raise funds for the many repairs it still needs to do on its own. One of the stranger money making schemes is the sale of the beer it brews. It also sells a booklet in English about the fort. This latter costs €4 and I would encourage visitors to buy one or the other. Stitching Fort Leizele vzw has a passion for the fort’s preservation and, while some of the displays look a bit amateurish, this is clearly for lack of funds and not competence.

On the last day of the tour we returned to London with a brief stop or two along the way. We saw far than I’ve related here, learning much. I found the trip invaluable as a research tool for my book Americans in a Splintering Europe: Refugees, Missionaries and Journalists in World War I. The trip was one of the best, if not the best, vacations I've ever taken. For those who desire to take a historical tour of Europe, I recommend Leger Holidays. Our guide, Marc Hope, did an excellent job, and several of my fellow travelers who’ve done other tours by Leger said they were excellent as well. If Leger doesn’t offer the tour you want, you can either ask someone there to create it, or try one of the many other companies that do the same kind of thing.🕜

Although all its original artillery pieces and other weapons were removed long ago, the rest of the structure remains intact. Among other places, we climbed to its top, entered a gas-proof room, and visited an entry bridge that, when retracted, reveals a deep, water-filled pit. In the room where the main gun once stood, I asked if those firing it had needed ear protection, or if anyone at time even thought that necessary. Our fortress guide informed me that sound went right out through the same ventilation system that kept the air fresh, so those firing the gun were spared the loud booms it made.

Because the fort is in part privately funded, the group that operates it, Stitching Fort Liezele vzw, has to raise funds for the many repairs it still needs to do on its own. One of the stranger money making schemes is the sale of the beer it brews. It also sells a booklet in English about the fort. This latter costs €4 and I would encourage visitors to buy one or the other. Stitching Fort Leizele vzw has a passion for the fort’s preservation and, while some of the displays look a bit amateurish, this is clearly for lack of funds and not competence.

On the last day of the tour we returned to London with a brief stop or two along the way. We saw far than I’ve related here, learning much. I found the trip invaluable as a research tool for my book Americans in a Splintering Europe: Refugees, Missionaries and Journalists in World War I. The trip was one of the best, if not the best, vacations I've ever taken. For those who desire to take a historical tour of Europe, I recommend Leger Holidays. Our guide, Marc Hope, did an excellent job, and several of my fellow travelers who’ve done other tours by Leger said they were excellent as well. If Leger doesn’t offer the tour you want, you can either ask someone there to create it, or try one of the many other companies that do the same kind of thing.🕜

Of the many of these we visited, the most striking is St. Symphorien Military Cemetery. Created by the Germans during the war, it was, according to the information plaque, “inaugurated on 6 September 1917.” The man who donated the land, Jean Honzeau, did so on the condition the Germans treat “the dead on both sides with honour.” It contains the bodies of many who fell at the Battle of Mons, the first clash between the British and Germans in 1914. And it was to Mons we headed on our first full day of touring.

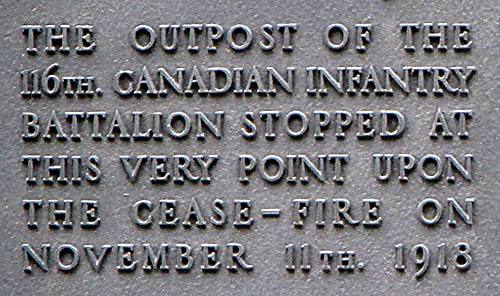

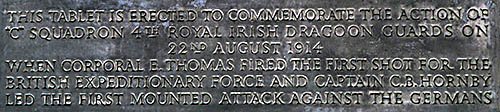

Along the way we stopped to visit a variety of places, including two memorial plaques, one on either side of the a busy two-lane highway. The memorial on our side of the road commemorated the first shot fired in the war by a soldier of the British Empire on August 22, 1914, the other the last soldier of the British Empire to die on November 11, 1918. Our guide pointed out that this shows just how far both sides moved in Belgium after four years of fighting.

Now imagine you are a construction worker across the road digging a bike path. You watch a tour coach stop to let out a hoard of people who start milling about the memorial plaque on the other side of the highway. Then, without warning, they begin crossing the busy road like a herd of elephants coming right for you. Your work interrupted, you violently toss your shovel away and began yelling in your native language of French, all the while gesturing theatrically. A fellow traveler said this construction worker accused us of being suicidal, presumably for crossing the busy road.

Near Nimy we went to another commemorative site, a railroad bridge, at which two British machine-gunners, Private Sidney Godley and Lieutenant Maurice James Dease, held off a German advance to give their comrades time to make an orderly retreat. Although both were seriously wounded, before departing, Godley had the presence of mind to disassemble the machine gun and throw it into the canal over which the bridge spanned so the Germans couldn’t use it. For this action both men received the first Victoria Crosses awarded in the war, Dease getting his posthumously because he died of his wounds.

We reached Mons at lunch time. As our coach stopped to let us off, our guide, Marc Hope, told us we needed to return here in an hour and a half. He gave us some vague directions as to where we might find food, then left with the coach because it couldn’t stay parked where it had dropped us off. We wandered around for half an hour looking for somewhere to eat. Not being able to read the local signage, we had to peek in each shop to see if it served food. And, unlike in Ieper, no one within these places save for an electronics store spoke a bit of English.

We settled on deli, or what we took for one, in which we resorted to improvised sign language and pointing. I got a baguette and what looked like a piece of garlic bread with cheese. With little garlic on it, it contained small pieces of a mystery meat that might have been horse for all I know. Still, it tasted good.

Along the way we stopped to visit a variety of places, including two memorial plaques, one on either side of the a busy two-lane highway. The memorial on our side of the road commemorated the first shot fired in the war by a soldier of the British Empire on August 22, 1914, the other the last soldier of the British Empire to die on November 11, 1918. Our guide pointed out that this shows just how far both sides moved in Belgium after four years of fighting.

Now imagine you are a construction worker across the road digging a bike path. You watch a tour coach stop to let out a hoard of people who start milling about the memorial plaque on the other side of the highway. Then, without warning, they begin crossing the busy road like a herd of elephants coming right for you. Your work interrupted, you violently toss your shovel away and began yelling in your native language of French, all the while gesturing theatrically. A fellow traveler said this construction worker accused us of being suicidal, presumably for crossing the busy road.

Near Nimy we went to another commemorative site, a railroad bridge, at which two British machine-gunners, Private Sidney Godley and Lieutenant Maurice James Dease, held off a German advance to give their comrades time to make an orderly retreat. Although both were seriously wounded, before departing, Godley had the presence of mind to disassemble the machine gun and throw it into the canal over which the bridge spanned so the Germans couldn’t use it. For this action both men received the first Victoria Crosses awarded in the war, Dease getting his posthumously because he died of his wounds.

We reached Mons at lunch time. As our coach stopped to let us off, our guide, Marc Hope, told us we needed to return here in an hour and a half. He gave us some vague directions as to where we might find food, then left with the coach because it couldn’t stay parked where it had dropped us off. We wandered around for half an hour looking for somewhere to eat. Not being able to read the local signage, we had to peek in each shop to see if it served food. And, unlike in Ieper, no one within these places save for an electronics store spoke a bit of English.

We settled on deli, or what we took for one, in which we resorted to improvised sign language and pointing. I got a baguette and what looked like a piece of garlic bread with cheese. With little garlic on it, it contained small pieces of a mystery meat that might have been horse for all I know. Still, it tasted good.

You could, I suppose, accuse me of being an ignorant American who expected the locals to speak English. I hadn’t even bothered, you might add, to learn some key phrases that might be of use, or at least carry a guide book. To this accusation I offer the following defense. I didn’t expect the locals to speak English, I have no tongue for foreign languages, and I chose to go on an English-speaking tour so I could avoid the very situation in which I found myself. Still, karma came into play. Our guide and two bus drivers got no lunch because they couldn’t find anywhere to park. For any tour guides reading this now, I have a suggestion to make. When you have a group that doesn’t speak the local language and you plan to let them go on their own in a strange city, hand out a little map of the area in which they will be walking, and include a list of places to get food, preferably with an annotation as to where there are likely to be English speakers. Two of our party got lost and it took some time to track them down.

During the last half hour of our break, we visited the Sainte-Waudru Collegiate Church. I’ve seen loads of photos of Gothic churches in my time but never stepped foot in a real one. The Roman Catholic Church built these structures in an effort to awe its flock and give it a taste of what Heaven would be like. This worked. The combination of altarpieces, Renaissance paintings and other decorative Church paraphernalia is enough to inspire even an atheist to believe in God, at least for a moment or two.

We began our second full day of the tour in Ieper itself at Menin Gate, a monument to the missing British soldiers who fought in and around Ieper during the war. Every night at 8 p.m. the local police host a memorial service for them, an event that draws a massive crowd. This, at the suggestion of our guide, we went to on our second night’s stay. Unlike the thick multitude of people there during the ceremony, if you visit early in the morning you’ll have the memorial to yourself. You can climb to the top on both sides. One extends quite far into a park while the other ends abruptly at Ieper’s walls with the moat below.

For lunch we stopped at Hooge Crater, a World War I site that doesn’t fall into the story of the Old Contemptibles but is still worth visiting. In 1915 the British Army’s Royal Engineers sent a tunneling company to begin digging here beneath German trenches with the idea of setting off an explosion that would displace them, allowing the British to advance. The engineers packed a mass of explosions into their tunnel and blew it on July 19, 1915. This created four connecting craters the British quickly occupied, at least for a time.

During the last half hour of our break, we visited the Sainte-Waudru Collegiate Church. I’ve seen loads of photos of Gothic churches in my time but never stepped foot in a real one. The Roman Catholic Church built these structures in an effort to awe its flock and give it a taste of what Heaven would be like. This worked. The combination of altarpieces, Renaissance paintings and other decorative Church paraphernalia is enough to inspire even an atheist to believe in God, at least for a moment or two.

We began our second full day of the tour in Ieper itself at Menin Gate, a monument to the missing British soldiers who fought in and around Ieper during the war. Every night at 8 p.m. the local police host a memorial service for them, an event that draws a massive crowd. This, at the suggestion of our guide, we went to on our second night’s stay. Unlike the thick multitude of people there during the ceremony, if you visit early in the morning you’ll have the memorial to yourself. You can climb to the top on both sides. One extends quite far into a park while the other ends abruptly at Ieper’s walls with the moat below.

For lunch we stopped at Hooge Crater, a World War I site that doesn’t fall into the story of the Old Contemptibles but is still worth visiting. In 1915 the British Army’s Royal Engineers sent a tunneling company to begin digging here beneath German trenches with the idea of setting off an explosion that would displace them, allowing the British to advance. The engineers packed a mass of explosions into their tunnel and blew it on July 19, 1915. This created four connecting craters the British quickly occupied, at least for a time.

Hooge Crater

Reconstructed Trench at Hooge Crater

WWI Artillery Shells at Hooge Crater

Model of Menin Gate found in Ieper

This is the present Nimy Rail Bridge, which looks like the original that was blown up.

Pillbox from WWI

Some Belgians keep deer fenced in so their properties qualify as farms so as to receive a lower tax rate.

Sainte-Waudru Cathedral (Mons)

King Albert I of Belgium

Nieuwpoort Visitor Center

Nieuwpoort Visitor Center

Nieuwpoort

Northernmost Point of World War I’s Trench System in Nieuwpoort

WWI Belgian Trench System