Benjamin Franklin Museum

Entrance

This is one of the animations found throughout the museum.

Franklin invented the armonica in 1761. Some believed it could drive a person insane.

The bust of Ben Franklin is a plaster copy of a sculpture by Jean-Antoine Houdon. This example is attributed to the Florentine Art Plaster Company.

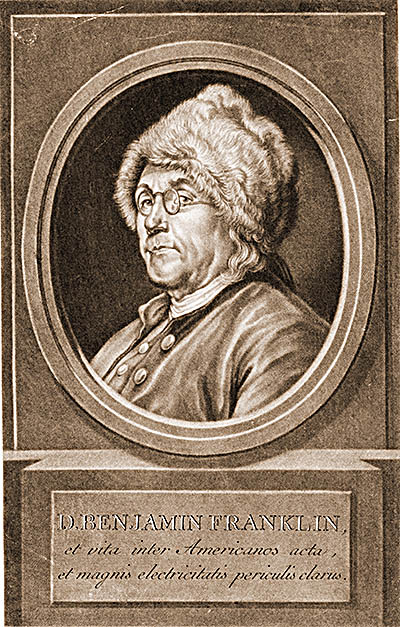

Print of Franklin by Johnann Elias Haid (1780)

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Bifocals produced during Franklin's lifetime.

This interactive touchscreen allows you to decide how to make your way from New York City to Philadelphia and tracks the amount of money you have to spend doing it.

Ink Balls Used for an 18th Century Printing Press

This penny is based on Franklin's paper money design.

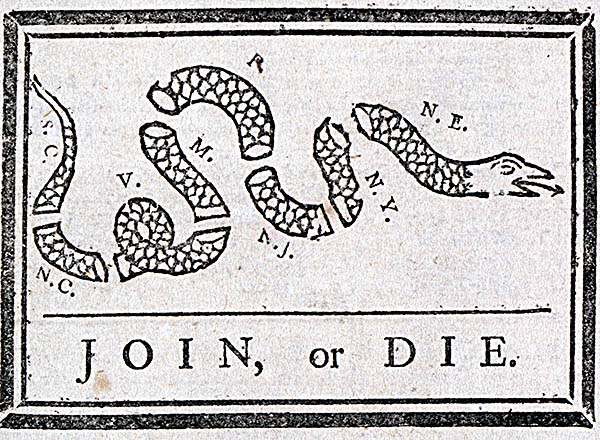

Franklin's most famous illustration suggested that if the colonies join together to support the British government during the French and Indian War.

Library of Congress.

Library of Congress.

Leyden Jars

Portrait of Mary (Polly) Stevenson, who Franklin treated like a daughter. It was done using pastels around 1770.

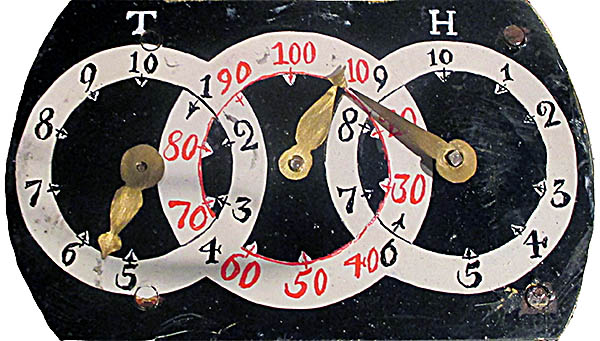

Franklin used an odometer like this while traveling as deputy postmaster.

This peace medal was engraved by Edward Duffy and struck by Joseph Richardson in 1757 to promote harmony with the native people of America. It was the first one made in the colonies.

Franklin invented the divided bowl for sea voyages.

This frame represents part of Frankin's house.

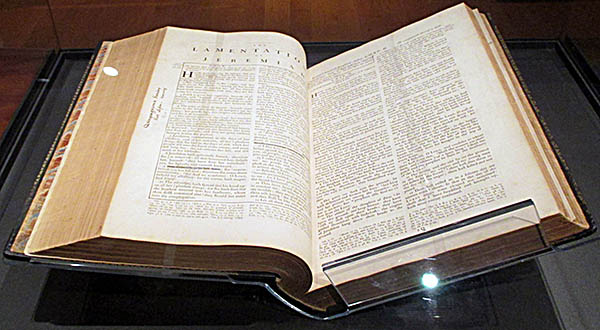

Franklin, an admirer of John Baskerville's work, bought this Bible printed by him. Franklin gave it to his daughter Sarah.

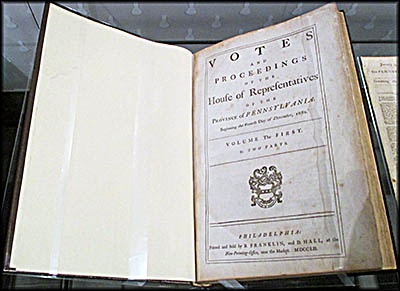

Franklin printed this book.

Despite following street signs and using two different phone-based GPS-driven walking maps, my traveling companions and I had trouble finding the Benjamin Franklin Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. We walked up and down Chester Street looking for it without luck. Fortunately, we came across a National Parks ranger who told us to go down a short alley to reach it. It’s buried amongst other buildings, and the fact that its exterior is uninspired and hardly screams that it’s a museum about Ben Franklin didn’t help. Although you enter at the street level, the museum proper is an underground floor.

It didn’t take long for me to realize I wasn’t its target audience. It’s geared towards children, and to that end has a number of goofy animations and interactive touchscreens to learn more about Franklin’s life and times. The museum, which opened in 1976, has few genuine artifacts that Franklin possessed or items from his era, probably because other museums and private collectors had long ago grabbed what was available.

Despite my criticisms, the museum is informative, and unless you’re a Franklin biographer, you’re sure to learn something about him that you didn’t already know. One thing I learned was that Franklin had a fondness for small, furry animals that he called “skuggs.” While in London, someone from the colonies sent him a gray squirrel that he kept as a pet. Alas, one day it escaped from its cage and a dog ate it. His wife, who’d stayed behind in Philadelphia, sent him a replacement.

It didn’t take long for me to realize I wasn’t its target audience. It’s geared towards children, and to that end has a number of goofy animations and interactive touchscreens to learn more about Franklin’s life and times. The museum, which opened in 1976, has few genuine artifacts that Franklin possessed or items from his era, probably because other museums and private collectors had long ago grabbed what was available.

Despite my criticisms, the museum is informative, and unless you’re a Franklin biographer, you’re sure to learn something about him that you didn’t already know. One thing I learned was that Franklin had a fondness for small, furry animals that he called “skuggs.” While in London, someone from the colonies sent him a gray squirrel that he kept as a pet. Alas, one day it escaped from its cage and a dog ate it. His wife, who’d stayed behind in Philadelphia, sent him a replacement.

The museum gives a brief but useful outline of Franklin’s life with a focus on his many inventions and other accomplishments. Born in Boston on January 17, 1707, he was the third of seventeen children. His father, Josiah, was a chandler—that is, he made soap and candles. Josiah called his shop the Blue Ball, a reference to the indigo he sold separately from soap. Normally used as a die to create a deep blue, you added indigo when rinsing your laundry. In those days textiles tended to yellow with age. The indigo counteracted this, making textiles appear whiter.

Franklin had no desire to be a chandler. He wanted to go to sea and threatened to run away if made to become one. Knowing his son loved reading, Josiah decided his son might do well as a printer, and to that end he apprenticed him to Ben’s older brother, James, who was a stern fellow. In addition to being a printer, James also published a newspaper. As an act of rebellion, Ben submitted pieces to it using the pseudonym Silence Dogood that his oblivious brother then printed. Over the years Ben used a bagful of pennames such as Abigail Twitterfield, Dr. Fatsides, Obadiah Plainman, and Sidi Mehemet Ibrhim.

Having had enough of James, the seventeen-year-old Ben ran away in 1723, first to New York City, then to Philadelphia. The museum didn’t, best I could tell, mention that running away from an apprenticeship in that era was illegal. Had James pressed the matter, he could’ve had his brother arrested and brought back to Boston.

Franklin had no desire to be a chandler. He wanted to go to sea and threatened to run away if made to become one. Knowing his son loved reading, Josiah decided his son might do well as a printer, and to that end he apprenticed him to Ben’s older brother, James, who was a stern fellow. In addition to being a printer, James also published a newspaper. As an act of rebellion, Ben submitted pieces to it using the pseudonym Silence Dogood that his oblivious brother then printed. Over the years Ben used a bagful of pennames such as Abigail Twitterfield, Dr. Fatsides, Obadiah Plainman, and Sidi Mehemet Ibrhim.

Having had enough of James, the seventeen-year-old Ben ran away in 1723, first to New York City, then to Philadelphia. The museum didn’t, best I could tell, mention that running away from an apprenticeship in that era was illegal. Had James pressed the matter, he could’ve had his brother arrested and brought back to Boston.

A museum information sign said that Franklin met his future wife, Deborah Read, on his first day in Philadelphia. It failed to mention that before their common law marriage in 1730, Franklin frequented brothels. He considered himself a Deist, meaning he believed in God but not miracles or divine intervention. His relationship with his wife was peculiar, as we shall see. The couple had three children: William, Francis (who died at the age of four), and Sarah (Sally).

Franklin made his living as a printer. To increase revenue, he established his own newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, and published the popular Poor Richard’s Almanac. His top-notch work earned him valuable government contracts. So successful was he, it allowed him to retire from printing at the age of forty-two.

Appointed deputy postmaster general for the colonies in 1753, during his tenure his introduced customer credit, printed forms and home delivery. Under his direction, the postal system turned a profit for the first time in its existence. He remained in this post even after moving to London in 1757 to represent the interests of Pennsylvania’s Assembly. He remained deputy postmaster until British government removed him from it in 1774.

Franklin made his living as a printer. To increase revenue, he established his own newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, and published the popular Poor Richard’s Almanac. His top-notch work earned him valuable government contracts. So successful was he, it allowed him to retire from printing at the age of forty-two.

Appointed deputy postmaster general for the colonies in 1753, during his tenure his introduced customer credit, printed forms and home delivery. Under his direction, the postal system turned a profit for the first time in its existence. He remained in this post even after moving to London in 1757 to represent the interests of Pennsylvania’s Assembly. He remained deputy postmaster until British government removed him from it in 1774.

Franklin took William with him to London but left Deborah behind. Returning home in 1762, the next year he hired master carpenter Robert Smith to build him a new Philadelphia house. He sailed back to London that that year, leaving Deborah behind so she could oversee the house’s construction and furnishing. She and Franklin never lived there together. She died in 1774, a year before his next return home in 1775. No one knows for certain if they had marital troubles.

During his first foray to London, he and William stayed in the house of the widow Margaret Stevenson. He became quite close with Margaret and in many ways she served as a surrogate wife, though whether or not the two were intimate is unknown. Franklin considered both Margaret and her daughter, Mary (Polly), family.

He may well have remained in London for the rest of his years had not the British government accused him of treason in 1774. To understand why, we need to go back to December 1772. In that month, Franklin received from an unknown person a packet of thirteen letters written by Massachusetts’ governor, Thomas Hutchinson, to his lieutenant governor, Andrew Oliver. In them Hutchinson suggested the best way to deal with the rebellious colonist was to reduce their liberties, send more troops to the colony, and eliminate local colonial governance.

During his first foray to London, he and William stayed in the house of the widow Margaret Stevenson. He became quite close with Margaret and in many ways she served as a surrogate wife, though whether or not the two were intimate is unknown. Franklin considered both Margaret and her daughter, Mary (Polly), family.

He may well have remained in London for the rest of his years had not the British government accused him of treason in 1774. To understand why, we need to go back to December 1772. In that month, Franklin received from an unknown person a packet of thirteen letters written by Massachusetts’ governor, Thomas Hutchinson, to his lieutenant governor, Andrew Oliver. In them Hutchinson suggested the best way to deal with the rebellious colonist was to reduce their liberties, send more troops to the colony, and eliminate local colonial governance.

Franklin forwarded the letters to Samuel Adams, who was head of the Massachusetts Committee of Correspondence. Franklin told Adams that he could show them to his fellow committee members but forbade him from copying or publishing them. Being rebels, they ignored Franklin and the letters’ contents became well known in the colonies.

On January 29, 1774, Franklin entered a room known as the Cockpit because of its former use for cock-fighting. Here he faced Britain’s Privy Council and during the session Lord Alexander Wedderburn berated him for an hour. Wedderburn accused Franklin of leaking the letters to incite riots against Britain. Despite a jeering crowd, Franklin kept silent during his humiliation and appeared impassive. He left for home the next year. Here he became a delegate for the Second Continental Congress where he served on the committee to write the Declaration of Independence.

In 1776, Franklin headed back to Europe, this time to France to seek help from the French government. He brought with him two grandsons. Over the next few years, he alongside other commissioners convinced the French to give the Patriots weapons, troops, and ships. (The last were critical in achieving the victory at Yorktown.) After the British defeat, Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay negotiated the Treaty of Paris that formally ended the American Revolution.

On January 29, 1774, Franklin entered a room known as the Cockpit because of its former use for cock-fighting. Here he faced Britain’s Privy Council and during the session Lord Alexander Wedderburn berated him for an hour. Wedderburn accused Franklin of leaking the letters to incite riots against Britain. Despite a jeering crowd, Franklin kept silent during his humiliation and appeared impassive. He left for home the next year. Here he became a delegate for the Second Continental Congress where he served on the committee to write the Declaration of Independence.

In 1776, Franklin headed back to Europe, this time to France to seek help from the French government. He brought with him two grandsons. Over the next few years, he alongside other commissioners convinced the French to give the Patriots weapons, troops, and ships. (The last were critical in achieving the victory at Yorktown.) After the British defeat, Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay negotiated the Treaty of Paris that formally ended the American Revolution.

Franklin traveled to Britain and Europe eight times during which he charted the Gulf Stream. Finding eating soup problematic while at sea, he invented a divided soup bowl, which had a large bowl in its center surrounded by smaller ones, allowing the liquid in the main bowl to slosh into the smaller ones instead of getting all over the table and deck.

Franklin came up with many inventions, never patenting them because he wanted them to benefit everyone. In addition to showing those that everyone is familiar with such as bifocal glasses and the Franklin stove, the museum also tell visitors about ones they probably don’t know came from Franklin’s fertile mind. He invented, as an example, windsurfing. He accomplished this by having a kite pull him across a pond.

He is best-known for his work with electricity and his famous kite experiment, which siphoned the energy of lightning into a Leyden jar—an early form of battery—to prove that lightning was electricity. From this experiment Franklin developed the lightning rod. He also coined the words “battery,” “negative charge” and “positive charge.”

Franklin came up with many inventions, never patenting them because he wanted them to benefit everyone. In addition to showing those that everyone is familiar with such as bifocal glasses and the Franklin stove, the museum also tell visitors about ones they probably don’t know came from Franklin’s fertile mind. He invented, as an example, windsurfing. He accomplished this by having a kite pull him across a pond.

He is best-known for his work with electricity and his famous kite experiment, which siphoned the energy of lightning into a Leyden jar—an early form of battery—to prove that lightning was electricity. From this experiment Franklin developed the lightning rod. He also coined the words “battery,” “negative charge” and “positive charge.”

In 1727 he and other like-minded tradesmen formed a club known as the Junto to promote the intellectual improvement of themselves and others. To further this goal, the Junto founded the Library Company of Philadelphia in 1731—America’s first lending library. In 1743, Franklin proposed a society that would promote useful knowledge, and out of this was born the American Philosophical Society. He helped found Philadelphia’s first voluntary fire brigade, and the Philadelphia Contributionship hat offered homeowners fire insurance, the Pennsylvania Hospital, and the colonies’ first non-religious college, the University of Philadelphia. He championed the creation of schools for free and enslaved Black children.

After the Revolution, he served two years as minister to France, finally going home in 1785. At this time he added to his house a print shop with a bindery, a foundry for one of his grandsons, and a new wing that included more bedrooms and a dining room. He also constructed two rental properties nearby, portions of which still stand on Market Street. Franklin died on April 17, 1790, at the age of eighty-four. By 1812 his grandchildren decided that they couldn’t be bothered with keep up his house, so they had it torn down and replaced with a couple rental properties.🕜

After the Revolution, he served two years as minister to France, finally going home in 1785. At this time he added to his house a print shop with a bindery, a foundry for one of his grandsons, and a new wing that included more bedrooms and a dining room. He also constructed two rental properties nearby, portions of which still stand on Market Street. Franklin died on April 17, 1790, at the age of eighty-four. By 1812 his grandchildren decided that they couldn’t be bothered with keep up his house, so they had it torn down and replaced with a couple rental properties.🕜