Zoar Village

Birthplace of Thomas Edison Museum

Edison Birthplace House Front

Edison Birthplace House Back

Evolution of Edison's phonographs with the oldest one on the right and the newest on the left.

One of the later models of phonograph complete with analog volume control by sticking a rag in the speaker, which is hidden behind a front panel.

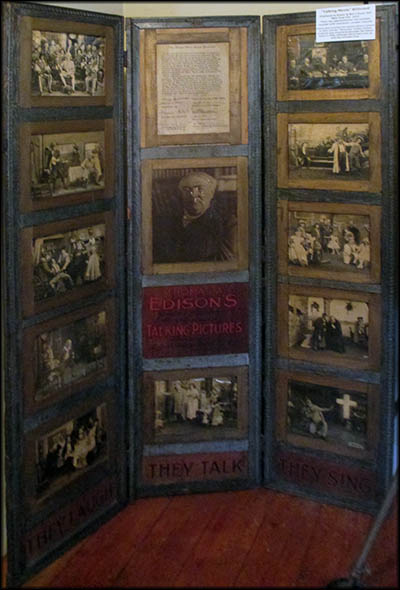

Display of Edison Movies with Sound

Cradle Rocker Used by Edison's Mother

Office where you pay to go through the museum.

Edison's Motoring Cape

Thomas Edison ca. 1893 taken by the J.M. White & Co. studio.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Sitting Room

Bedrooms

Parlor

Kitchen

It’s true you rarely visit the tourist attractions near you. I’ve lived close to the Birthplace Museum of Thomas Alva Edison for most of my life and only visited once as a child, which I don’t recall because of my young age. These days Edison’s birthplace house, which is in Milan, Ohio, is a mere eight minutes as the car drives from my home. The museum has two houses. The one on the left is the office and gift shop where you buy tickets. The one on the right is Edison’s house. The office has a variety of phonographs and movie making equipment on display, and the person who sells the ticket gives you some history about their development. The phonograph, I learned, was the invention that Edison was proudest of. He called the prototype the Shout Machine because that’s what you had to do if you wanted to record your voice. Edison was completely deaf in one ear and severely hard of hearing in the other, so his employees had to do the listening. (An aside: he didn’t invent a hearing aid because he found the silence welcome—it away kept distractions when he was working).

His initial test was a recording of “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” It sounded terrible but it was the first time the human voice was recorded and played back. This earliest version of the phonograph produced such poor sound that it went no where commercially. The tin foil proved to be too fragile and didn’t do a good job of recording sound. It was Alexander Graham Bell, Chichester A. Bell (Alexander’s cousin), and Charles Sumner Tainter who developed and patented the far superior wax cylinder that they used for their version of the phonograph that they called the graphophone.

His initial test was a recording of “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” It sounded terrible but it was the first time the human voice was recorded and played back. This earliest version of the phonograph produced such poor sound that it went no where commercially. The tin foil proved to be too fragile and didn’t do a good job of recording sound. It was Alexander Graham Bell, Chichester A. Bell (Alexander’s cousin), and Charles Sumner Tainter who developed and patented the far superior wax cylinder that they used for their version of the phonograph that they called the graphophone.

Edison returned to the phonograph and he, too, went with wax cylinders. But they had their own issues, the biggest of which is too much heat caused the wax to melt. In 1908 Edison began making phonograph cylinders out of plastic. This surprised me. I thought plastic was invented in the mid-twentieth century, but no, Belgian chemist Leo Baekeland created it in 1907. He beat his Scottish rival, James Swinburne, to the patent office by one day. Edison’s plastic cylinders were commercially sold as Blue Amberol Records. He later switched to flat disks that could hold five minutes of sound per side.

He envisioned the phonograph strictly for recording voices in an office setting. It was soon repurposed for music, but he still saw value in recording for business purposes and came out with the Ediphone to do this. The idea was that it would replace stenographers, but it never took off.

Edison didn’t invent motions pictures (it was Frenchman Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince who did that), but he did corner the market in the United States. In 1891 the Kinetoscope was introduced. This was a machine where you viewed a short movie via a peephole. Edison took out the patent but it was one of his assistants, William Kennedy Dickson, who created it. He tried to introduce sound but was stymied by because he couldn’t keep it synchronized with the film. This was a problem he never solved, and by the time someone figured it out, he’d had long been out of the moving making business.

He envisioned the phonograph strictly for recording voices in an office setting. It was soon repurposed for music, but he still saw value in recording for business purposes and came out with the Ediphone to do this. The idea was that it would replace stenographers, but it never took off.

Edison didn’t invent motions pictures (it was Frenchman Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince who did that), but he did corner the market in the United States. In 1891 the Kinetoscope was introduced. This was a machine where you viewed a short movie via a peephole. Edison took out the patent but it was one of his assistants, William Kennedy Dickson, who created it. He tried to introduce sound but was stymied by because he couldn’t keep it synchronized with the film. This was a problem he never solved, and by the time someone figured it out, he’d had long been out of the moving making business.

Edison also made America’s first movies in a purpose-built studio nicknamed the Black Maria because of its similarity to the black wagons police used to transport criminals. It was built in West Orange, New Jersey. In those days filming required extremely bright light, so the top of the studio opened to allow sunlight in. Since the sun moves throughout the day, the studio was designed to rotate, which was done by the staff pushing it around. Edison eventually abandoned it and moved the operation into a glass studio in the Bronx that cost $100,000 to build.

So far the focus was on Edison’s inventions, but that changes at the house. Here a new guide takes over. The house tour is less about Edison’s inventions and more about his early life and how middle class people lived in the mid-nineteenth century. I knew nothing about Edison’s father, Samuel Ogden Edison, Jr., but found his story more compelling than his son’s. Thomas’ grandfather, John Edison, lived in New Jersey when the American Revolution broke out. A Loyalist, he was nearly executed, so in 1784 he relocated to Nova Scotia, and it’s here his son, Samuel, was born on August 16, 1804.

So far the focus was on Edison’s inventions, but that changes at the house. Here a new guide takes over. The house tour is less about Edison’s inventions and more about his early life and how middle class people lived in the mid-nineteenth century. I knew nothing about Edison’s father, Samuel Ogden Edison, Jr., but found his story more compelling than his son’s. Thomas’ grandfather, John Edison, lived in New Jersey when the American Revolution broke out. A Loyalist, he was nearly executed, so in 1784 he relocated to Nova Scotia, and it’s here his son, Samuel, was born on August 16, 1804.

Sam wasn’t as keen on the British as his father, and he got involved in a rebellion against Canada’s elite led by William Lyon Mackenzie. Fueled by an economic depression and crop failure, the insurrection occurred in December 1837 but quickly collapsed. Sam feared for his life. He went to his father, John, for help, but he refused and told Sam he’d best leave the country. So Sam did, but without his wife and four children. A friend of his suggested he go to Milan, Ohio, where a canal connecting to the navigable part of Huron River and thence to Lake Erie was being dug.

The canal was dug by hand and its basin was forty feet wide and thirteen feet deep. It served as a place for farmers to ship their grain, and at it’s peak, Milan was the world’s second largest grain port, the only larger one being in Odessa, Ukraine. Milan also had a shipbuilding industry that made seventy-five schooners. Competition from railroads reduced the town’s prosperity, and a flood in 1868 put the canal out of business for good.

Sam opened a wooden shingle making business, the only one in the area. With help from his friend Captain Alva Bradley, he moved his family to Milan about seven to eight months after settling down. His business didn’t make the family rich, but it did well enough that Sam was able to barter or otherwise acquire the materials needed to build the house in which Thomas would be born on February 11, 1847. It took Sam two years to complete it, which he did with his own hands. From the street the house looks rather small, one of the reasons I thought a tour of it would be short. How wrong I was. It’s built into a hill and has a total of three levels. The main floor contains a parlor, a bedroom and a sitting room. Upstairs are more bedrooms, and downstairs is the kitchen.

The canal was dug by hand and its basin was forty feet wide and thirteen feet deep. It served as a place for farmers to ship their grain, and at it’s peak, Milan was the world’s second largest grain port, the only larger one being in Odessa, Ukraine. Milan also had a shipbuilding industry that made seventy-five schooners. Competition from railroads reduced the town’s prosperity, and a flood in 1868 put the canal out of business for good.

Sam opened a wooden shingle making business, the only one in the area. With help from his friend Captain Alva Bradley, he moved his family to Milan about seven to eight months after settling down. His business didn’t make the family rich, but it did well enough that Sam was able to barter or otherwise acquire the materials needed to build the house in which Thomas would be born on February 11, 1847. It took Sam two years to complete it, which he did with his own hands. From the street the house looks rather small, one of the reasons I thought a tour of it would be short. How wrong I was. It’s built into a hill and has a total of three levels. The main floor contains a parlor, a bedroom and a sitting room. Upstairs are more bedrooms, and downstairs is the kitchen.

The house was not especially warm during Ohio’s cold months. The sitting room had a stove and fireplaces in the parlor and kitchen. Fireplaces an are exceedingly inefficient way of heating a room and wouldn’t have helped much. Upstairs there was no heat at all. Edison’s parents were disciplinarians who frequently employed the switch. None of the children were allowed in the parlor without permission, and this room was only used to host guests. Little leisure time existed. In addition to regular chores, the girls had to do needlework at night. The boys were responsible for making candles using beeswax. Chamber pots had to be emptied daily.

One of the Samuel’s daughters, Marion, married Homer Page in the house in 1849. She was just fifteen, not an uncommon age for a young lower or middle class woman to marry in those days. During her wedding she likely wore a corset, a device that could squeeze the waist down to as much as fifteen inches. There is an example of a dress with a wasp-like waist worn by Thomas’ second wife, Mina Miller, in the house.

Also here you can see Edison’s motoring cape, his favorite homburg hat, and his leather cane. Edison only lived in the house for the first seven years of his life. His father moved the family to Port Huron in 1854 because the canal and ship making businesses were slowing down. In Port Huron, Edison only had two months of formal education. He didn’t do well in a school environment, but his mother, Nancy, had some formal education and tutored her son. Edison learned much from reading books.

One of the Samuel’s daughters, Marion, married Homer Page in the house in 1849. She was just fifteen, not an uncommon age for a young lower or middle class woman to marry in those days. During her wedding she likely wore a corset, a device that could squeeze the waist down to as much as fifteen inches. There is an example of a dress with a wasp-like waist worn by Thomas’ second wife, Mina Miller, in the house.

Also here you can see Edison’s motoring cape, his favorite homburg hat, and his leather cane. Edison only lived in the house for the first seven years of his life. His father moved the family to Port Huron in 1854 because the canal and ship making businesses were slowing down. In Port Huron, Edison only had two months of formal education. He didn’t do well in a school environment, but his mother, Nancy, had some formal education and tutored her son. Edison learned much from reading books.

One of the former bedrooms on the first floor displays a variety of Edison’s inventions. Here I learned he invented wax paper and a talking doll. The latter used a miniature phonograph that sounded creepy. The doll was also expensive and didn’t sell well. Also in the room is a lightbulb, possibly the invention Edison is best known for. Except he neither invented the incandescent light bulb nor was he the first to improve upon it. By the time he began work, the longest lasting one could stay on for about thirteen hours before burning out. His goal was to create one that lasted far longer. He based his lightbulb on patents purchased from Matthew Evans and Henry Woodward. He created an improved vacuum bulb in which he tried a variety of filaments until finding one that lasted: bamboo coated with carbon. He got the bamboo from Japan’s Kyoto Prefecture. This bulb lasted for 1,200 hours and didn’t cost a fortune to make.

For the next forty years after Samuel sold the house, other families owned and lived in it. Edison had fond memories of the place and in 1894 his sister, Marion Edison Page, bought it. She updated it, adding an indoor bathroom and other modern conveniences, although when Thomas visited in 1923, he was surprised that it was still lit by candles and oil lamps. Electricity and modern lighting were later added. Henry Ford, one of Edison’s best friends, tried and failed to get Edison to sell the house so it could be moved to Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan. Edison refused because his father had built the house and it felt it ought to stay put.

Edison died on October 18, 1931. The birthplace house remained in the family with Edison’s wife, Mina, and one of his daughters, Madeleine Edison Sloane. These two decided to restore it to a state as close to what it was when Edison lived there as possible. It opened in 1947. One of Edison’s descendants still sits on the museum’s board.🕜

For the next forty years after Samuel sold the house, other families owned and lived in it. Edison had fond memories of the place and in 1894 his sister, Marion Edison Page, bought it. She updated it, adding an indoor bathroom and other modern conveniences, although when Thomas visited in 1923, he was surprised that it was still lit by candles and oil lamps. Electricity and modern lighting were later added. Henry Ford, one of Edison’s best friends, tried and failed to get Edison to sell the house so it could be moved to Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan. Edison refused because his father had built the house and it felt it ought to stay put.

Edison died on October 18, 1931. The birthplace house remained in the family with Edison’s wife, Mina, and one of his daughters, Madeleine Edison Sloane. These two decided to restore it to a state as close to what it was when Edison lived there as possible. It opened in 1947. One of Edison’s descendants still sits on the museum’s board.🕜

Model of Edison's "Black Maria" Studio