Although many sea hands had no formal education, their work nonetheless required a high degree of intelligence and a good memory. They had to learn an entire lexicon of specialized jargon, such as “grit-line” and “storm-jib,” applying this knowledge to tasks such being able to tie twenty different knots or trimming a sail to make it catch the wind most efficiently. Judging by the sculptures and etchings some of them produced, one can safely say that mariners also had among themselves some undiscovered artistic geniuses.

Merchant mariners did not remain passive about their lot in life or their lack of power. Tired of the economic blackmailing perpetrated by crimps, they gathered together and formed powerful seamen’s unions that used collective power to hold strikes to force their wages up so as to get them out of perpetual debt. These unions also successfully lobbied Congress to get the draconian laws against them changed. In 1915 their work paid off: President Wilson signed the Seamen’s Act, which, among other important reforms, removed the ability of authorities to force men to sail against their will. And without that, shanghaiing died.🕜

Merchant mariners did not remain passive about their lot in life or their lack of power. Tired of the economic blackmailing perpetrated by crimps, they gathered together and formed powerful seamen’s unions that used collective power to hold strikes to force their wages up so as to get them out of perpetual debt. These unions also successfully lobbied Congress to get the draconian laws against them changed. In 1915 their work paid off: President Wilson signed the Seamen’s Act, which, among other important reforms, removed the ability of authorities to force men to sail against their will. And without that, shanghaiing died.🕜

Copyright © 2014 by Mark Strecker

BLOOD MONEY, LANDSHARKS,

AND SEAMEN: A BRIEF

HISTORY OF SHANGHAIING

AND SEAMEN: A BRIEF

HISTORY OF SHANGHAIING

Drugged, made drunk, or tricked: these and other techniques snagged thousands of men into involuntary servitude on board the ships sailing around the world. Called shanghaiing, it plagued the seafaring world from about 1849 to 1915. A collusion of events as diverse as the popularity of tea, the addiction of a nation to opium, and the discovery of gold created a perfect storm of events that made it extremely profitable to sell men into virtual slavery for a fee known as blood money. Those who shanghaied men—called crimps, sea pimps, or landsharks—targeted mainly the seafaring class because their low social standing meant few of importance cared about their fate. A ruling by the Supreme Court made American seamen indentured servants the moment they signed a ship’s contract—the ship’s articles—or stepped on board a naval ship, this after the Thirteenth Amendment ended slavery. After this ruling American law treated sailing hands like children under the erroneous belief this class of men could not take care of themselves.

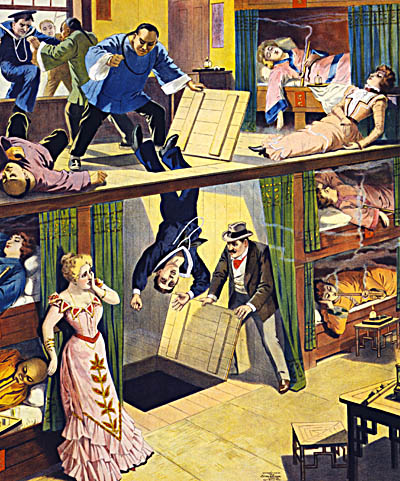

This illustration perpetuated the myth that crimps used trapdoors to shanghai sailors.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Three Brothers

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Life at sea had little to offer save for hardship, terror, and brutality at the hands of officers. For this reason too few men willingly took up the profession of seaman, making the demand higher than the supply and explaining why captains turned to shanghaiing to procure men. Romanticized in popular culture, it has become a useful plot device in works of fiction: have a protagonist fall through a trapdoor then wake up on the ship, and your tale can go anywhere in the world. Although a few victims of shanghaiing found themselves on adventures of a lifetime complete with danger and plot twists, most did not. None fell through trapdoors.

Crimps often tricked men into signing the ship’s articles to make them legally bound to sail. Authorities could and did arrest those who refused or deserted, then forced them back on board. Crimps often owned sailors’ boardinghouses. They extended their lodgers credit, then charged criminal prices for everything from room and board to liquor to clothes. In that era many states had debtors’ prisoners, allowing boardinghouse crimps to extort their victims by giving them choice of sailing on a ship of the crimp’s choice or going to jail.

Of all the kinds of ships crimps could force victims onto, few had a fouler reputation than whalers. Experienced seamen knew to avoid these “hell ships” at all costs. Whaler crews received no regular wages but rather a share, or lay, of the final profits. Unscrupulous captains deducted the cost of food, clothes, and anything else the crewmen needed in order to make them owe more at the voyage’s end than they had earned, thus inducing them to sail on the next voyage to make up the difference. Only those seduced by the romanticism of the whaling industry or tricked into believing they would receive an unrealistic percentage of the total profits willingly signed on.

Crimps often tricked men into signing the ship’s articles to make them legally bound to sail. Authorities could and did arrest those who refused or deserted, then forced them back on board. Crimps often owned sailors’ boardinghouses. They extended their lodgers credit, then charged criminal prices for everything from room and board to liquor to clothes. In that era many states had debtors’ prisoners, allowing boardinghouse crimps to extort their victims by giving them choice of sailing on a ship of the crimp’s choice or going to jail.

Of all the kinds of ships crimps could force victims onto, few had a fouler reputation than whalers. Experienced seamen knew to avoid these “hell ships” at all costs. Whaler crews received no regular wages but rather a share, or lay, of the final profits. Unscrupulous captains deducted the cost of food, clothes, and anything else the crewmen needed in order to make them owe more at the voyage’s end than they had earned, thus inducing them to sail on the next voyage to make up the difference. Only those seduced by the romanticism of the whaling industry or tricked into believing they would receive an unrealistic percentage of the total profits willingly signed on.

The poor conditions on the oyster dredgers of the Chesapeake Bay equaled those of whale ships. Ill-fed and ill-treated, the men upon them did backbreaking work with little reward. Like whalers, men avoided working on these, forcing dredger captains to purchase hands from crimps. The oystermen went to war among themselves as well, making life on board their vessels even more dangerous. The battles among themselves as well as extensive pouching forced Maryland and Virginia to establish special navies to police them.

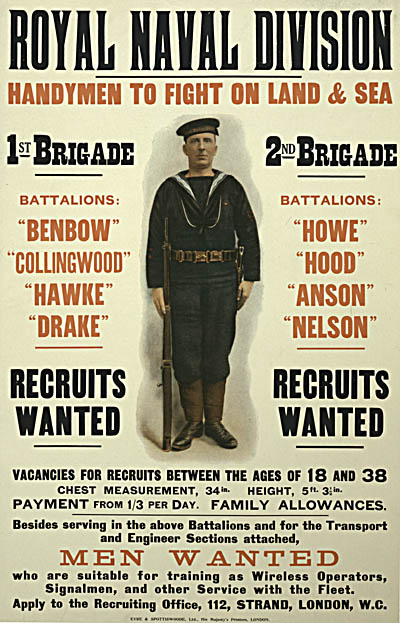

Merchant ships and fishing fleets did not have a monopoly on shanghaiing. Navies practiced it, too, only they called it impressment. Unlike a shanghaied man, who usually had to serve on a single voyage before getting off, a pressed sailor might have to serve for years if not decades, released only when a war ended or he successfully deserted. Britain’s Royal Navy (RN) liked to target the poor because their low status and lack of personal power made them easy targets; even when fined, the RN preferred to pay the fee and keep the man.

In the American colonies the RN used impressment so frequently it decimated the population of towns and cities; needless to say, American colonists resisted it when possible. After the colonies became the United States, the RN continued its practice of pressing Americans. Often RN captains claimed to look for deserters, and, in all fairness, they did find them, but they also took many American citizens. Outraged Americans called for war against Britain, and in 1812 got it. The RN ended the practice not because Britain “lost” this conflict, but because that nation had beat Napoleon and had no need for a massive navy.

Merchant ships and fishing fleets did not have a monopoly on shanghaiing. Navies practiced it, too, only they called it impressment. Unlike a shanghaied man, who usually had to serve on a single voyage before getting off, a pressed sailor might have to serve for years if not decades, released only when a war ended or he successfully deserted. Britain’s Royal Navy (RN) liked to target the poor because their low status and lack of personal power made them easy targets; even when fined, the RN preferred to pay the fee and keep the man.

In the American colonies the RN used impressment so frequently it decimated the population of towns and cities; needless to say, American colonists resisted it when possible. After the colonies became the United States, the RN continued its practice of pressing Americans. Often RN captains claimed to look for deserters, and, in all fairness, they did find them, but they also took many American citizens. Outraged Americans called for war against Britain, and in 1812 got it. The RN ended the practice not because Britain “lost” this conflict, but because that nation had beat Napoleon and had no need for a massive navy.