Blundering into Victory

BLUNDERING INTO VICTORY

Copyright © 2005, 2012 by Mark Strecker

Captain Oliver Hazard Perry, USN (1795–1819)

By Edward L. Mooney.

Wikimedia Commons

By Edward L. Mooney.

Wikimedia Commons

Isaac Chancey

Naval Historical Center

Naval Historical Center

The Battle of Lake Erie took place during the War of 1812, a conflict neither Great Britain nor the majority of U.S. citizens and politicians wanted. It occurred not because of perceived grievances toward Great Britain but rather dreams of territorial expansion, especially into Florida and Canada. After the declaration of war, U.S. forces attempted and failed to invade Canada on several occasions. Of these, those based out of Ohio and the Northwest Territory found themselves hampered by the one thing they could not effectively wage war upon: nature. Thick forests, treacherous swamps, and raging rivers stood in the way. In addition to these formidable obstacles, travelers had to beware of hostile Native Americans. Using Lakes Erie, Champlain and Ontario would make moving men and materials much faster and far easier, but the British dominated these bodies of water.

When Barclay arrived, the Royal Navy only had one war vessel under construction, the Detroit, which would not be ready until August. Even if she could have launched earlier, it would have done little good as Barclay lacked the men in general and experienced mariners in particular to man her. He expressed his frustration over this situation in a letter he wrote to Captain Yeo: “[T]here are two Gun boats without a man—Thus you may observe that the state of the Squadron on the lake is by no means so well manned and equipped as you were led to believe and candidly (with the exception of about 10) the Men which I bought with me are but little calculated to make them better.”

To complicate matters, Barclay lacked sufficient supplies. His vessels had inadequate amounts of food for a lengthy cruise. He needed rope, iron, shot, powder, and cannon for the Detroit. He solved the cannon problem by raiding the Amherstburg fort of its armaments, but this left him with a hodgepodge of sizes and a lack of ammunition to fit them. Of the men he recruited, landsman made up the majority. This meant that even if he could get them trained to fire the cannon, he still lacked an adequate number of experienced mariners to do the actual sailing. He also needed a sufficient pool of officers to command.

Perry, too, complained about his men. He wrote to Chauncey grumbling about how he had received men of an unacceptable standard, made worse by the fact that Chauncey had kept the best ones for himself. Frustrated, Perry circumvented his commander’s authority and asked for more men directly from the Secretary of Navy. Chauncey did not take kindly to this breach in the chain of command. He and Perry got into a war of words via letters, and at one point Perry resigned over the matter, which he later withdrew. Chauncey finally relented and sent him more skilled men.

Barclay, meanwhile, made surveys of Presque Island, writing with enthusiasm: “I am told that Presque Isle is a bare harbour [sic] & that there is not above 6 feet of water on it—if it is so, the Vessels must come out off the harbour [sic] to be rigged and armed, & that they shall never accomplish if it is in my power to prevent it.” This same bravado did not infect the rest of the correspondence to his superiors in the Navy as well as to army officers. He pleaded to both for the support of a land force that would launch an attack against the harbor in coordination with his own. No one would give him the troops. Perry’s own intelligence told him he outmanned Barclay significantly. In July the new secretary of the navy, William Jones, reported in a letter to him: “According to their account, the British Naval force in men cannot be above 220 or 30, which would give you, even without any further reinforcement, a decided superiority.”

Perry received his first chance to see combat in May when Chauncey invited him to participate in the upcoming attack on Fort George, a stronghold that stood at the mouth of the Niagara River. The U.S. Navy had a ship building facility at Black Rock farther down but could not launch its vessels into Lake Erie without passing under Fort George’s guns. To free them up and seriously disrupt the British supply lines, General William Henry Harrison planned an amphibious attack against the fort.

Perry headed to Buffalo, New York, via rowboat, and from there made his way to Commodore Chauncey’s flagship, the Madison. Chauncey put Perry in charge of 500 marines and seamen, who would support Colonel Winfield Scott. Shortly after the attack began at 3:00 a.m., Perry learned from an American schooner that the British planned to stand and fight, which American battle planners did not think would occur. Perry rowed to shore, warned Harrison of this, then returned to the lake. Next he ordered the line of boats he commanded to withdraw farther away from the shore to ensure they did not accidentally fire upon American troops. He boarded the nine-gun Hamilton and ordered her to fire canister and grape shot at the enemy. Here he showed that he at least could make clear decisions under fire, an ability only useful for one who also possessed good judgment.

To complicate matters, Barclay lacked sufficient supplies. His vessels had inadequate amounts of food for a lengthy cruise. He needed rope, iron, shot, powder, and cannon for the Detroit. He solved the cannon problem by raiding the Amherstburg fort of its armaments, but this left him with a hodgepodge of sizes and a lack of ammunition to fit them. Of the men he recruited, landsman made up the majority. This meant that even if he could get them trained to fire the cannon, he still lacked an adequate number of experienced mariners to do the actual sailing. He also needed a sufficient pool of officers to command.

Perry, too, complained about his men. He wrote to Chauncey grumbling about how he had received men of an unacceptable standard, made worse by the fact that Chauncey had kept the best ones for himself. Frustrated, Perry circumvented his commander’s authority and asked for more men directly from the Secretary of Navy. Chauncey did not take kindly to this breach in the chain of command. He and Perry got into a war of words via letters, and at one point Perry resigned over the matter, which he later withdrew. Chauncey finally relented and sent him more skilled men.

Barclay, meanwhile, made surveys of Presque Island, writing with enthusiasm: “I am told that Presque Isle is a bare harbour [sic] & that there is not above 6 feet of water on it—if it is so, the Vessels must come out off the harbour [sic] to be rigged and armed, & that they shall never accomplish if it is in my power to prevent it.” This same bravado did not infect the rest of the correspondence to his superiors in the Navy as well as to army officers. He pleaded to both for the support of a land force that would launch an attack against the harbor in coordination with his own. No one would give him the troops. Perry’s own intelligence told him he outmanned Barclay significantly. In July the new secretary of the navy, William Jones, reported in a letter to him: “According to their account, the British Naval force in men cannot be above 220 or 30, which would give you, even without any further reinforcement, a decided superiority.”

Perry received his first chance to see combat in May when Chauncey invited him to participate in the upcoming attack on Fort George, a stronghold that stood at the mouth of the Niagara River. The U.S. Navy had a ship building facility at Black Rock farther down but could not launch its vessels into Lake Erie without passing under Fort George’s guns. To free them up and seriously disrupt the British supply lines, General William Henry Harrison planned an amphibious attack against the fort.

Perry headed to Buffalo, New York, via rowboat, and from there made his way to Commodore Chauncey’s flagship, the Madison. Chauncey put Perry in charge of 500 marines and seamen, who would support Colonel Winfield Scott. Shortly after the attack began at 3:00 a.m., Perry learned from an American schooner that the British planned to stand and fight, which American battle planners did not think would occur. Perry rowed to shore, warned Harrison of this, then returned to the lake. Next he ordered the line of boats he commanded to withdraw farther away from the shore to ensure they did not accidentally fire upon American troops. He boarded the nine-gun Hamilton and ordered her to fire canister and grape shot at the enemy. Here he showed that he at least could make clear decisions under fire, an ability only useful for one who also possessed good judgment.

Robert Barclay

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Capture of Fort George (Col. Winfield Scott Leading the Attack)

by Alopage Chappel

Library of Congress

by Alopage Chappel

Library of Congress

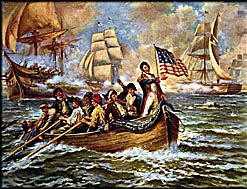

Battle of Lake Erie

by Percy Morgan. Library of Congress.

by Percy Morgan. Library of Congress.

Perry’s Victory on Lake Erie, Sept. 10th, 1813

by J.J. Barralet

Engraved by B. Tanner

Library of Congress

by J.J. Barralet

Engraved by B. Tanner

Library of Congress

At the battle’s successful conclusion, Chauncey ordered Perry to retrieve four vessels at Black Rock to add to his squadron at Erie. With no men to spare, Chauncey asked General Dearborn if his subordinate could borrow 200 infantrymen for the task. Dearborn acquiesced. Because the Niagara River flows away from Lake Erie with a strong current, it took a grueling week of work involving both men and teams of oxen to get the four vessels into the lake proper despite the fact only three miles separated Black Rock from the river’s mouth.

Perry sailed his newly acquired vessels back to Presque Isle Harbor, giving him a total of ten vessels. His newly constructed gunboats launched without trouble, but the larger brigs Lawrence and Niagara could not do so easily as they had to pass over the sandbar. Their drafts of nine feet would not allow them to pass the four feet above it. To make things more complicated, Barclay’s squadron arrived to prevent Perry from getting his unarmed and unrigged brigs out.

Fortunately for him, Barclay up and sailed away one day. One American account claimed that he had left to attend a dinner, but both Barclay’s letters and the transcript of his court martial clearly show otherwise. As a diligent and dedicated British officer, he would have shot his remaining arm off before leaving his post for such an arbitrary reason. His squadron had departed because it had run out of food.

Perry knew how to get the brigs over the sandbar. He had at his disposal camels, water tight wooden boxes equipped with pumps. Constructed on site, they worked as such. A team of men sunk them by flooding their interiors with water. Next they placed one under either side of a vessel’s keel, then connected them with strong beams. Once secured, the pumps removed the water within and the resulting buoyancy lifted the brigs up high enough to float over the sandbar.

Perry moved the Lawrence out first. This took two days of hard work because no one there had ever used camels. With experience gained, it took them much less time to move the Niagara out. Although Barclay returned before Perry could arm and outfit his brigs, the British lieutenant only viewed them from a distance, and in doing so mistakenly believed Perry had them ready for action. Not prepared for a fight, Barclay withdrew.

Perry rigged and armed the brigs by July 23. On July 30, he received a letter from Chauncey telling him to take full command of the squadron and to search out and destroy the British squadron. Chauncey could not come in person after all because he had not yet secured Lake Ontario. On August 3, he sent another master commandant, Jesse Elliott, to take a contingent of eleven officers and ninety-one men to bolster Perry’s crews, who gave Elliott command of the Niagara and made the Lawrence his flagship. Elliott, who had recently distinguished himself by boldly capturing two vessels from Fort Erie, picked his men from those he had brought without consulting Perry. Always one who liked harmony with his subordinates, he said nothing.

The squadron of ten ships left the harbor on August 6, 1813, returned to Erie the next day, then established its home port at Put-In-Bay. From here Perry set out to find Barclay, but he could not find the enemy squadron. He complained his letters about his frustration that it seemed unwilling to engage him. Barclay, however, had no intention of fighting until he had his new ship, the Detroit, ready for action. His men (what few he had) still needed extensive training; he also needed qualified seamen to navigate and do the sailing.

When Perry learned Barclay’s squadron remained in Amherstburg, he sailed up the Detroit River to survey it, although he dared not attack lest he come in range of the fort’s guns. He sailed back to Put-in-Bay with the idea of somehow enticing Barclay to leave his safe harbor, not knowing of Barclay’s manning situation. Major General Henry Procter of the British Army offered to send Barclay “50 seamen with two Lieutts. and one Midshipman,” but only thirty-six men arrived, including two lieutenants, one master’s mate, and two gunners. Barclay tried his best to stay in port, but on September 8, 1813, Procter ordered him to engage Perry with what he had.

Barclay left with fifty experienced seamen, officers included, to distribute among his six vessels. Many of his men spoke only French, making training them all the more difficult. When he left harbor, he had the crew on half-rations as he only possessed a day’s worth of flour and no spirits save for that reserved for times of action—something that could inspire a mutiny in that era. He lacked usable tubes and fuses for his cannon. To fire them, his gunners had to discharge pistols (less the ammunition) into the touchholes. With all these deficiencies, it seemed a foregone conclusion he would lose.

Perry’s squadron first sighted Barclay’s at sunrise on September 10, 1813. At this time Perry had nine vessels under his command because he had sent his tenth to retrieve supplies. In his battle plan, he had assigned each of his craft to engage a specific enemy vessel, simultaneously ordering his commanders to not break the battle line. This created a bit of dilemma. Should they leave the line to engage their assigned adversary, or stay put as ordered?

Perry assigned the Lawrence and Niagara to engage Barclay’s two ships, the Detroit and Queen Charlotte. The Caledonia from Black Rock, a smaller brig, would support the Lawrence with her long guns. Most of Perry’s vessels rated as gunboats, which meant they carried only long guns, cannon designed to damage an enemy vessel from afar. The Lawrence and Niagara carried mostly carronades, close range cannon that fired both solid cannonballs and grapeshot capable of inflicting far more damage on an enemy’s hull and rigging than long guns.

Perry sailed his newly acquired vessels back to Presque Isle Harbor, giving him a total of ten vessels. His newly constructed gunboats launched without trouble, but the larger brigs Lawrence and Niagara could not do so easily as they had to pass over the sandbar. Their drafts of nine feet would not allow them to pass the four feet above it. To make things more complicated, Barclay’s squadron arrived to prevent Perry from getting his unarmed and unrigged brigs out.

Fortunately for him, Barclay up and sailed away one day. One American account claimed that he had left to attend a dinner, but both Barclay’s letters and the transcript of his court martial clearly show otherwise. As a diligent and dedicated British officer, he would have shot his remaining arm off before leaving his post for such an arbitrary reason. His squadron had departed because it had run out of food.

Perry knew how to get the brigs over the sandbar. He had at his disposal camels, water tight wooden boxes equipped with pumps. Constructed on site, they worked as such. A team of men sunk them by flooding their interiors with water. Next they placed one under either side of a vessel’s keel, then connected them with strong beams. Once secured, the pumps removed the water within and the resulting buoyancy lifted the brigs up high enough to float over the sandbar.

Perry moved the Lawrence out first. This took two days of hard work because no one there had ever used camels. With experience gained, it took them much less time to move the Niagara out. Although Barclay returned before Perry could arm and outfit his brigs, the British lieutenant only viewed them from a distance, and in doing so mistakenly believed Perry had them ready for action. Not prepared for a fight, Barclay withdrew.

Perry rigged and armed the brigs by July 23. On July 30, he received a letter from Chauncey telling him to take full command of the squadron and to search out and destroy the British squadron. Chauncey could not come in person after all because he had not yet secured Lake Ontario. On August 3, he sent another master commandant, Jesse Elliott, to take a contingent of eleven officers and ninety-one men to bolster Perry’s crews, who gave Elliott command of the Niagara and made the Lawrence his flagship. Elliott, who had recently distinguished himself by boldly capturing two vessels from Fort Erie, picked his men from those he had brought without consulting Perry. Always one who liked harmony with his subordinates, he said nothing.

The squadron of ten ships left the harbor on August 6, 1813, returned to Erie the next day, then established its home port at Put-In-Bay. From here Perry set out to find Barclay, but he could not find the enemy squadron. He complained his letters about his frustration that it seemed unwilling to engage him. Barclay, however, had no intention of fighting until he had his new ship, the Detroit, ready for action. His men (what few he had) still needed extensive training; he also needed qualified seamen to navigate and do the sailing.

When Perry learned Barclay’s squadron remained in Amherstburg, he sailed up the Detroit River to survey it, although he dared not attack lest he come in range of the fort’s guns. He sailed back to Put-in-Bay with the idea of somehow enticing Barclay to leave his safe harbor, not knowing of Barclay’s manning situation. Major General Henry Procter of the British Army offered to send Barclay “50 seamen with two Lieutts. and one Midshipman,” but only thirty-six men arrived, including two lieutenants, one master’s mate, and two gunners. Barclay tried his best to stay in port, but on September 8, 1813, Procter ordered him to engage Perry with what he had.

Barclay left with fifty experienced seamen, officers included, to distribute among his six vessels. Many of his men spoke only French, making training them all the more difficult. When he left harbor, he had the crew on half-rations as he only possessed a day’s worth of flour and no spirits save for that reserved for times of action—something that could inspire a mutiny in that era. He lacked usable tubes and fuses for his cannon. To fire them, his gunners had to discharge pistols (less the ammunition) into the touchholes. With all these deficiencies, it seemed a foregone conclusion he would lose.

Perry’s squadron first sighted Barclay’s at sunrise on September 10, 1813. At this time Perry had nine vessels under his command because he had sent his tenth to retrieve supplies. In his battle plan, he had assigned each of his craft to engage a specific enemy vessel, simultaneously ordering his commanders to not break the battle line. This created a bit of dilemma. Should they leave the line to engage their assigned adversary, or stay put as ordered?

Perry assigned the Lawrence and Niagara to engage Barclay’s two ships, the Detroit and Queen Charlotte. The Caledonia from Black Rock, a smaller brig, would support the Lawrence with her long guns. Most of Perry’s vessels rated as gunboats, which meant they carried only long guns, cannon designed to damage an enemy vessel from afar. The Lawrence and Niagara carried mostly carronades, close range cannon that fired both solid cannonballs and grapeshot capable of inflicting far more damage on an enemy’s hull and rigging than long guns.

Perry's Victory

by Thomas Birch. Library of Congress.

by Thomas Birch. Library of Congress.

Perry needed to tack towards Barclay, but the wind’s lightness made the process slow. When Perry got into range of Barclay’s long guns at 11:45 a.m., the wind shifted in Perry’s favor, giving him what mariners call the weather gage. The calm lake water allowed his gunboats to maneuver far better than his larger vessels, yet he placed them at the end of his line rather than in more effective positions.

Now came the most amazing part of this whole encounter. After Perry signaled an attack, only the Lawrence, Caledonia, Ariel, and Scorpion moved into battle. The Niagara started toward the Queen Charlotte, but when fired upon, suddenly held back and fired ineffectually at long range. The other four other vessels, the gunboats Somers, Porcupine, Tigress, and Trippe, all stalled due to lack of wind, keeping them out of the battle as well.

Of Barclay’s squadron, only the Detroit and Queen Charlotte had experienced officers in charge as well as a mere sixteen experienced gunners who knew how to fight with cannon on the water. Barclay had made the Detroit his flagship, leaving the Queen Charlotte under the charge of a lieutenant in command ten officers and 110 men, far too few for her to fight effectively. In the opening volleys of the battle, she lost her two senior officers, leaving an inexperienced provincial lieutenant in charge of, beyond ordinary and able seamen, one master’s mate, two extremely young acting midshipmen, two warrant officers, a boatswain, and one professional gunner. Despite the deficiency, she and the Detroit relentlessly pounded at the Lawrence for two hours, blasting the Lawrence’s rigging to pieces and killing eighty of the 119 men on board, although Perry himself remained unscathed. During this time Elliott never ordered the Niagara to assist.

Barclay suffered from a grievous wound to his thigh and another to his remaining arm, forcing him to go below for surgery. During his absence the inexperienced officer in charge of his flagship tried to move her away and instead collided with the Queen Charlotte, leaving the two ships entangled and relatively helpless. Now Perry’s gunboats had an easy target.

When the Lawrence’s maneuverability became impossible, Perry decided to change flagships. He turned command over to a Lieutenant Yarnall and told him to fight on while he and several others boarded a longboat and rowed to the Niagara. Although the Detroit’s crew saw Perry’s departure, it had no way to give chase as its own boat had suffered destruction. Despite his order to the contrary, Lieutenant Yarnall surrendered the Lawrence, but the crew of the trapped Detroit could not board because her prey lay too far away.

Now came the most amazing part of this whole encounter. After Perry signaled an attack, only the Lawrence, Caledonia, Ariel, and Scorpion moved into battle. The Niagara started toward the Queen Charlotte, but when fired upon, suddenly held back and fired ineffectually at long range. The other four other vessels, the gunboats Somers, Porcupine, Tigress, and Trippe, all stalled due to lack of wind, keeping them out of the battle as well.

Of Barclay’s squadron, only the Detroit and Queen Charlotte had experienced officers in charge as well as a mere sixteen experienced gunners who knew how to fight with cannon on the water. Barclay had made the Detroit his flagship, leaving the Queen Charlotte under the charge of a lieutenant in command ten officers and 110 men, far too few for her to fight effectively. In the opening volleys of the battle, she lost her two senior officers, leaving an inexperienced provincial lieutenant in charge of, beyond ordinary and able seamen, one master’s mate, two extremely young acting midshipmen, two warrant officers, a boatswain, and one professional gunner. Despite the deficiency, she and the Detroit relentlessly pounded at the Lawrence for two hours, blasting the Lawrence’s rigging to pieces and killing eighty of the 119 men on board, although Perry himself remained unscathed. During this time Elliott never ordered the Niagara to assist.

Barclay suffered from a grievous wound to his thigh and another to his remaining arm, forcing him to go below for surgery. During his absence the inexperienced officer in charge of his flagship tried to move her away and instead collided with the Queen Charlotte, leaving the two ships entangled and relatively helpless. Now Perry’s gunboats had an easy target.

When the Lawrence’s maneuverability became impossible, Perry decided to change flagships. He turned command over to a Lieutenant Yarnall and told him to fight on while he and several others boarded a longboat and rowed to the Niagara. Although the Detroit’s crew saw Perry’s departure, it had no way to give chase as its own boat had suffered destruction. Despite his order to the contrary, Lieutenant Yarnall surrendered the Lawrence, but the crew of the trapped Detroit could not board because her prey lay too far away.

At this point Barclay had the advantage. Unlike Perry, he had lost no ships, and if he could get the rest of his force to bear down on the strangely idle Niagara, he had a very good chance of winning. Much controversy surrounds why Elliott refused to sail into battle. One account stated that when Perry boarded the Niagara, Elliott had already left, having rowed to those vessels still lagging behind to get them into the battle. Another version claimed Perry spat some harsh words at Elliott, then ordered him to rally the lingering vessels.

In his own account, Elliot stated that Perry had said to him: “‘I believe the damned gun boats [sic] have lost me the day.’” To this Elliott replied, “I hope not sir; my ship is now in a judicious position; take charge of my battery, and I will bring up the small vessels and save the day!” Elliott further claimed that he had moved the Niagara into her position to allow the Caledonia to pass. Some of his supporters also maintained he had not wanted to break from the line as originally ordered.

In an 1839 book entitled Battle of Lake Erie with Notices of Commodore Elliot’s [sic] Conduct in That Engagement, historian Tristam Burges damned Elliott’s conduct and proved beyond a doubt (in his mind, at least) that Elliott had stayed put due to cowardice and neglect of duty. Perry himself, not wanting to mar the “glory” of his victory with in-fighting, ordered his men to keep silent about the matter. Elliott continued to insist on his own heroism. After several years of hearing this, a disgusted Perry organized a court martial charging Elliott with, among other things, cowardice and neglect of duty. The Navy refused to allow the trial to proceed because it did not want two of its most esteemed officers fighting so publicly.

After taking command of the Niagara, Perry sailed her into battle. Had Barclay not lost his competent officers which resulted in the entanglement of his two ships, he might have stood a chance at defeating the oncoming attack from the Niagara. But the Detroit and Queen Charlotte became free of one another far too late. Facing both the Niagara and the four fresh American gunboats proved too much for his squadron. He surrendered. British writer and Barclay contemporary William James complained bitterly about Perry keeping the Niagara out of action for so long—how unfair! During Barclay’s court martial, many officers who had participated in the battle had this same sentiment.

Two of Barclay’s vessels tried and failed to escape. Perry took his prizes and prisoners back to Put-in-Bay, where he allowed them to rest, attend to their wounded, and write reports to their superiors. Parsons, the only surgeon active on the American side because all other medical personnel had suffered from an unnamed sickness (probably malaria), found himself overwhelmed by the wounded, but he persevered, receiving praises from Perry and a promotion to the rank of surgeon. Barclay’s court martial cleared he and his men of any misconduct and considered them heroes for nearly winning the battle despite having insufficient men and materials.

With the battle won, Perry wrote this famous note the General William Henry Harrison: “We have met the enemy and they are ours: Two Ships, two Brigs, one Schooner & one Sloop. Yours, with great respect and esteem. O.H. Perry.” Perry’s famous message also has an infamous mistake: he misidentified the schooner Lady Provost as a brig, meaning he had actually taken one brig and two schooners. He notably made no claim in this nor any other correspondence of a spectacular victory. He won by failing to lose.🕜

In his own account, Elliot stated that Perry had said to him: “‘I believe the damned gun boats [sic] have lost me the day.’” To this Elliott replied, “I hope not sir; my ship is now in a judicious position; take charge of my battery, and I will bring up the small vessels and save the day!” Elliott further claimed that he had moved the Niagara into her position to allow the Caledonia to pass. Some of his supporters also maintained he had not wanted to break from the line as originally ordered.

In an 1839 book entitled Battle of Lake Erie with Notices of Commodore Elliot’s [sic] Conduct in That Engagement, historian Tristam Burges damned Elliott’s conduct and proved beyond a doubt (in his mind, at least) that Elliott had stayed put due to cowardice and neglect of duty. Perry himself, not wanting to mar the “glory” of his victory with in-fighting, ordered his men to keep silent about the matter. Elliott continued to insist on his own heroism. After several years of hearing this, a disgusted Perry organized a court martial charging Elliott with, among other things, cowardice and neglect of duty. The Navy refused to allow the trial to proceed because it did not want two of its most esteemed officers fighting so publicly.

After taking command of the Niagara, Perry sailed her into battle. Had Barclay not lost his competent officers which resulted in the entanglement of his two ships, he might have stood a chance at defeating the oncoming attack from the Niagara. But the Detroit and Queen Charlotte became free of one another far too late. Facing both the Niagara and the four fresh American gunboats proved too much for his squadron. He surrendered. British writer and Barclay contemporary William James complained bitterly about Perry keeping the Niagara out of action for so long—how unfair! During Barclay’s court martial, many officers who had participated in the battle had this same sentiment.

Two of Barclay’s vessels tried and failed to escape. Perry took his prizes and prisoners back to Put-in-Bay, where he allowed them to rest, attend to their wounded, and write reports to their superiors. Parsons, the only surgeon active on the American side because all other medical personnel had suffered from an unnamed sickness (probably malaria), found himself overwhelmed by the wounded, but he persevered, receiving praises from Perry and a promotion to the rank of surgeon. Barclay’s court martial cleared he and his men of any misconduct and considered them heroes for nearly winning the battle despite having insufficient men and materials.

With the battle won, Perry wrote this famous note the General William Henry Harrison: “We have met the enemy and they are ours: Two Ships, two Brigs, one Schooner & one Sloop. Yours, with great respect and esteem. O.H. Perry.” Perry’s famous message also has an infamous mistake: he misidentified the schooner Lady Provost as a brig, meaning he had actually taken one brig and two schooners. He notably made no claim in this nor any other correspondence of a spectacular victory. He won by failing to lose.🕜

In an effort to reverse this situation, the U.S. secretary of the navy sent Captain Isaac Chauncey to take control of Lakes Ontario and Erie, setting up his base of operations at Sacket’s Harbor on Lake Ontario. The secretary of the navy decided he wanted a new squadron built for Lake Erie as well, so he asked the advice of a Pennsylvania-based merchant captain named Daniel Dobbins as to what location would work best. Dobbins suggested Presque Island Bay at Erie, Pennsylvania. As a natural harbor, it had a sandbar blocking its small entrance that would keep most unwanted vessels out.

The secretary made Dobbins a sailing master (a position often awarded to merchant captains who joined the U.S. Navy), gave him $2,000, and told him to build four gunboats. Dobbins began contracting workers and materials and, on September 26, 1812, construction began. Chauncey later ordered Dobbins to build two brigs in addition to the gunboats. Although constantly hampered by a lack of supplies (except for wood), the construction proceeded unhindered by the British. The shipwrights and carpenters there would only build the hulls and add masts. Other specialists had to rig and arm them. This meant Chauncey needed to find someone experienced to oversee the latter stage of the ship building operation.

Before the coming of the war, a naval lieutenant named Oliver Hazard Perry had come to Washington, D.C., begging for the command of a ship as he had received word Congress would soon declare war. He wanted to see action, something he had never experienced since joining the Navy as a midshipman at the age of sixteen. His most notable feat up to that time had come when he lost a schooner, the Revenge, off the coast of his home state of Rhode Island. Despite this, he managed to receive a promotion to master commandant, but it came with no command.

This he received on June 18, 1812, the day Congress declared war against Britain. His orders told him to take command of a “fleet” of gunboats at Newport, Rhode Island. When he arrived, he found the Navy had siphoned off so many of his men he had only eight left for each boat, far too few with whom he could do any sailing. Despite his inexperience, Perry did one valuable skill: he knew how to rig and outfit naval vessels. Knowing this, a friend of his recommended he put in for the command position opening on Lake Erie. He balked. He wanted to sail on the oceans, not some lake in the middle of nowhere.

He nonetheless wrote Chauncey and asked for the posting, mentioning he would bring with him 100 men. Chauncey could hardly believe his good fortune. Here he could solve two problems at once. First, he would get an officer who had experience rigging and arming sailing vessels. Second, he would acquire qualified mariners as he lacked a sufficient pool. He accepted Perry’s request to serve under him, ordering him to take temporary command of the squadron at Presque Island Harbor until he himself could arrive.

Because American naval ranks differed significantly in Perry’s day, it seems prudent to give a few details about his and others before 1815. The rank of master commandant equaled commander in today’s navy. It effectively created a junior captain who, by law, could not command any vessel with twenty-one or more guns. Directly under this rank came lieutenant, and, below that, midshipman. As in the Royal Navy, when a lieutenant or master commandant took command of a vessel (almost never one classified as a “ship”), the men on board called him “captain.”

In contemporary letters written by other naval officials to or about Perry, they usually referred to him as such. No American rank rated higher than captain until 1815, and that of commodore did not become official until the Civil War, although those who commanded a squadron of vessels received it in an honorary capacity, and they could use it even if commanding a single vessel. People therefore referred to Captain Chauncey as a commodore, as they did for Perry when he took full command of his squadron.

When Perry arrived at Sacket’s Harbor to meet with his new commander, he found things not to his liking. Chauncey commandeered a third of his men and would not allow him leave for fear of an impending attack on the base. (He almost always thought the enemy had the advantage, so he only went into a battle if he had virtually no chance of losing.) After two weeks, Perry took a sleigh over the frozen lake to Presque Isle Bay. There he plunged into the task of finding men and supplies and getting the new vessels launched.

As he did this, Lieutenant Robert Heriot Barclay, a far more competent and battle-hardened seaman than Perry, took command of Lake Erie’s British squadron. The problems Barclay faced made Perry’s look minor. The British commander in charge of all lake operations, Captain Sir James Lucas Yeo, had earlier offered this command to a captain named Mulcaster, but the moment he saw squadron’s state, he refused. Yeo offered it to Barclay and he, like any ambitious junior naval officer in the Royal Navy, took it. The five vessels in his new squadron had formally served as merchant craft before their draft into military service. Their builders had intended them to transport cargo, not fight battles.

The secretary made Dobbins a sailing master (a position often awarded to merchant captains who joined the U.S. Navy), gave him $2,000, and told him to build four gunboats. Dobbins began contracting workers and materials and, on September 26, 1812, construction began. Chauncey later ordered Dobbins to build two brigs in addition to the gunboats. Although constantly hampered by a lack of supplies (except for wood), the construction proceeded unhindered by the British. The shipwrights and carpenters there would only build the hulls and add masts. Other specialists had to rig and arm them. This meant Chauncey needed to find someone experienced to oversee the latter stage of the ship building operation.

Before the coming of the war, a naval lieutenant named Oliver Hazard Perry had come to Washington, D.C., begging for the command of a ship as he had received word Congress would soon declare war. He wanted to see action, something he had never experienced since joining the Navy as a midshipman at the age of sixteen. His most notable feat up to that time had come when he lost a schooner, the Revenge, off the coast of his home state of Rhode Island. Despite this, he managed to receive a promotion to master commandant, but it came with no command.

This he received on June 18, 1812, the day Congress declared war against Britain. His orders told him to take command of a “fleet” of gunboats at Newport, Rhode Island. When he arrived, he found the Navy had siphoned off so many of his men he had only eight left for each boat, far too few with whom he could do any sailing. Despite his inexperience, Perry did one valuable skill: he knew how to rig and outfit naval vessels. Knowing this, a friend of his recommended he put in for the command position opening on Lake Erie. He balked. He wanted to sail on the oceans, not some lake in the middle of nowhere.

He nonetheless wrote Chauncey and asked for the posting, mentioning he would bring with him 100 men. Chauncey could hardly believe his good fortune. Here he could solve two problems at once. First, he would get an officer who had experience rigging and arming sailing vessels. Second, he would acquire qualified mariners as he lacked a sufficient pool. He accepted Perry’s request to serve under him, ordering him to take temporary command of the squadron at Presque Island Harbor until he himself could arrive.

Because American naval ranks differed significantly in Perry’s day, it seems prudent to give a few details about his and others before 1815. The rank of master commandant equaled commander in today’s navy. It effectively created a junior captain who, by law, could not command any vessel with twenty-one or more guns. Directly under this rank came lieutenant, and, below that, midshipman. As in the Royal Navy, when a lieutenant or master commandant took command of a vessel (almost never one classified as a “ship”), the men on board called him “captain.”

In contemporary letters written by other naval officials to or about Perry, they usually referred to him as such. No American rank rated higher than captain until 1815, and that of commodore did not become official until the Civil War, although those who commanded a squadron of vessels received it in an honorary capacity, and they could use it even if commanding a single vessel. People therefore referred to Captain Chauncey as a commodore, as they did for Perry when he took full command of his squadron.

When Perry arrived at Sacket’s Harbor to meet with his new commander, he found things not to his liking. Chauncey commandeered a third of his men and would not allow him leave for fear of an impending attack on the base. (He almost always thought the enemy had the advantage, so he only went into a battle if he had virtually no chance of losing.) After two weeks, Perry took a sleigh over the frozen lake to Presque Isle Bay. There he plunged into the task of finding men and supplies and getting the new vessels launched.

As he did this, Lieutenant Robert Heriot Barclay, a far more competent and battle-hardened seaman than Perry, took command of Lake Erie’s British squadron. The problems Barclay faced made Perry’s look minor. The British commander in charge of all lake operations, Captain Sir James Lucas Yeo, had earlier offered this command to a captain named Mulcaster, but the moment he saw squadron’s state, he refused. Yeo offered it to Barclay and he, like any ambitious junior naval officer in the Royal Navy, took it. The five vessels in his new squadron had formally served as merchant craft before their draft into military service. Their builders had intended them to transport cargo, not fight battles.