Buck Rogers Saves America

Kaiser Wilhelm II

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

In 1896, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany did something unprecedented for the head a major European empire: he drew a political cartoon. With his own artistic skill somewhat limited, he handed his sketch over to a professional and asked him to produce a final version. The Kaiser’s illustration contained a group of Valkyries led by a sword-wielding angel standing upon a cliff overlooking Europe. Above the group floated a cross, and on the other side of Europe stood a silhouetted Buddha enveloped by flames. A variation of this illustration replaced the Buddha with a fanged skull shaped to look East Asian.

BUCK ROGERS SAVES AMERICA

Copyright © 2012 by Mark Strecker.

“Nations of Europe! Join in the Defense of Your Faith!”

Final illustration based on Kaiser Willhelm II’s sketch.

Final illustration based on Kaiser Willhelm II’s sketch.

Not until the 1842 did Europeans finally make inroads into that country when the British forced China to sign an unequal treaty upon the latter’s loss of the First Opium War, an agreement that resulted in the addition of Hong Kong to the British Empire and opened five Chinese ports (in addition to Canton) to all Western nations. It further granted Britain sovereignty over its own subjects in China itself, a privilege several other Western nations plus Japan also enjoyed. The Second Opium War resulted in an 1858 treaty that gave foreigners access into China’s interior beyond the treaty ports. Western missionaries seized upon this opportunity and rushed in to proselytize, sending back home some of the first modern Western eyewitness accounts of China’s people, geography, and government. China’s vastness and untapped natural resources, in addition to its massive population, made Westerners nervous because they feared if China modernized and started expanding beyond its traditional borders, it could pose a serious threat to the West.

Alarm that China might become a rival power to the West sparked the science fiction subgenre of near-future war scenarios, the first of which, “The Battle of Dorking” by Sir George Tomkyns Chesney, appeared in 1871 in the British monthly Blackwood’s Magazine. The genre developed to include another popular plot device, the fifth column. In this scenario, when China attacks, those Chinese already living in America—or a European nation with a significant Chinese minority rise up—form militias, and start massacring unsuspecting civilians.

Alarm that China might become a rival power to the West sparked the science fiction subgenre of near-future war scenarios, the first of which, “The Battle of Dorking” by Sir George Tomkyns Chesney, appeared in 1871 in the British monthly Blackwood’s Magazine. The genre developed to include another popular plot device, the fifth column. In this scenario, when China attacks, those Chinese already living in America—or a European nation with a significant Chinese minority rise up—form militias, and start massacring unsuspecting civilians.

Christopher Lee as Fu Manchu in Castle of Fu Manchu (Tower London Studios)

Still taken from the trailer.

Still taken from the trailer.

Commodore Matthew C. Perry

Photo by Mathew B. Brady

Library of Congress

Photo by Mathew B. Brady

Library of Congress

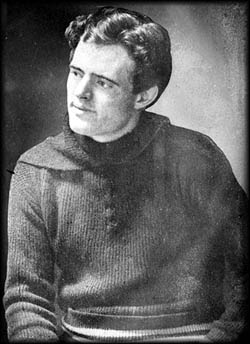

Jack London

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

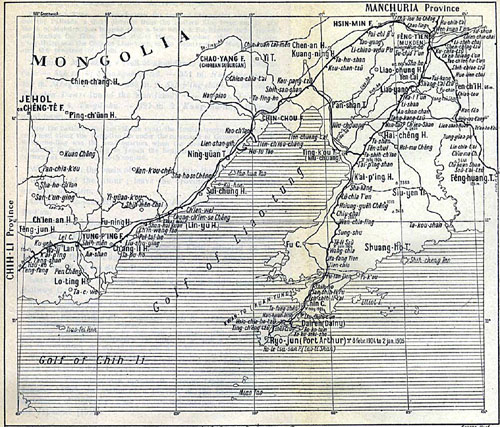

Map of South Manchuria

Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collecion

University of Texas, Austin

Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collecion

University of Texas, Austin

Max von Sydow as Ming the Merciless in the 1980 movie Flash Gordon (Universal)

Still taken from the trail. Note his similarity of Fu Manchu.

Still taken from the trail. Note his similarity of Fu Manchu.

Copyright © Hermes Press. Used with permission.

In America, the Yellow Peril had its origins in the California Gold Rush and started purely out of jealousy. Rather than find new claims, the Chinese who came as gold hunters took over abandoned mining camps considered exhausted by their previous American owners. Through perseverance the new proprietors made these supposedly played out claims start producing once more. Envious Americans invaded the successful Chinese camps to rob and in some cases kill these foreigners. As the Gold Rush died, railroad building in the West increased. In the Pacific states and territories, greedy railroad companies brought in cheap Chinese labor to undercut the prevailing wage. Americans did not take kindly to this competition. The Panic of 1857 exasperated this situation, turning animosity into outright hostility.

The Yellow Peril also extended into China proper. Americans and Western Europeans working or having interests there worried that the local people would rise up and resist the foreign presence. This fear became a reality in 1900 when a Chinese religious movement, the Yihequan (Righteous and Harmonious Fists), started to kill Christian missionaries and other foreigners in an effort to drive them out of their homeland because they had grown tired of being treated as second-class citizens in their own country, and they resented the taint of Christianity on their culture. Their use of ritual martial arts prompted Westerners to call them the Boxers and term their uprising the Boxer Rebellion. While a coalition of European powers plus America and Japan made short work of this “insurrection,” the dread of it happening on a larger scale led to the creation of the Fu Manchu character by British writer Sax Rohmer.

This Chinese criminal mastermind embodied the characteristics of what the English feared most: a Chinese who understood and used Western technology and who could successfully lead his people in conquest against the British Empire. Within a few pages of the first story, “The Mystery of Fu Manchu,” the protagonist, British agent Sir Denis Nayland Smith, tells the story’s narrator he needs to stop a plot that threatens the existence of the entire white race. For all his racial “superiority,” however, Smith never catches or kills Fu Manchu in any of the books and shorter works.

In the year of the Boxer Rebellion, China controlled an area of 4,460,000 square miles and had a population of about four million. A 1907 article that appeared in The North American Review predicted the Mongolian race (usually meant to include the Chinese, Japanese, Koreans and ethnic Mongolians) would make up one-third of the world’s population in the near future, and went on to outline the terrible things that could happen to the West if left unchecked. It did not matter whether the article’s statistics had any validity. Just appearing in a magazine as prominent as The North American Review made them as good as true. (According to The World Almanac and Encyclopedia 1912, the total world population stood at 1,520,150,000. Of this, East Asians made up 630,000,000 and whites 625,000,000, meaning the former consisted of about 40 percent of the total population and the latter 41 percent, hardly the disparity the Yellow Peril alarmists would have liked people to believe.) Japan’s stunning 1905 victory over Russia in the Russo-Japanese War only served to heighten the fears of the

Yellow Peril because until this moment no modern Western power had ever suffered a defeat from an Far Eastern nation. The triumph had taken the West off guard in large part because only fifty-two years earlier, Japanese society still clung to its feudal, agrarian past. Since its borders had remained closed to most outsiders, the West knew little of it or its people until 1853 when Commodore Matthew C. Perry of the U.S. Navy arrived with his squadron of modern warships to force it to open up trade. The Japanese, technologically outmatched, reluctantly acquiesced. Perry irreversibly changed Japanese culture and government on a scale similar to Nicolaus Copernicus’ revelation that the Earth rotated around the Sun or Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. Within a generation of Perry’s arrival, the Japanese emperor—with the help if not the pressure of his advisors—established a parliamentary system of government, eliminated the rigid class system, and replaced the samurai with a modern conscription army. The country began the process of industrialization and formed a modern navy.

Japan feared European powers would takeover its islands in a way similar to what they had done to China, so it decided to establish an empire of its own to serve as a buffer zone against this. To that end, it gained control of Formosa and Korea after fighting a brief war with China in 1894–1895 (the incident that had prompted the Kaiser to produce his cartoon), then went to war with Russia in 1904 to wrest from it control of the Liaotung Peninsula, an important piece of real estate because it granted easy access into the rest of Manchuria.

Jack London, having witnessed the Russo-Japanese War as a reporter, did not like what he had seen. In 1904, he published an essay about the subject titled “The Yellow Peril.” It began by praising the resilience of the Chinese and offered a hardy admiration of their capacity to continue their day to day lives despite war all around them as well as their ability and willingness to embrace new ideas brought in from the West. Americans, London decided, had nothing to fear from the Chinese because their government kept them submissive and subservient. The Japanese, on the other hand, had proved themselves both aggressive and adept war makers. London warned that if Japan ever took control of the Chinese and directed them to make war, their population of 400 million could readily overwhelm the West.

London followed this notion up in his 1910 short story “The Unparalleled Invasion.” Set in 1976, this near-future war tale tells the “history” of the world after the Japanese triumph over Russia in 1905. The Japanese do indeed try to harness the power of the Chinese as London predicted in his essay, but the attempt fails and leads to Japan’s ruin. Following this, China awakens and becomes a major industrial power. Rather than outright conquer other nations, the Chinese government sends overwhelming numbers of colonists into those places it wants. When an external Chinese militia invades, the Chinese colonists rise up to make conquest quick and easy (the fifth column theme). Alarmed, European nations try and fail to do something about it. France, for example, sends into China an army of a quarter of a million men, but before this force reaches Beijing, the massive Chinese population swallows it up, leaving no survivors.

The Yellow Peril also extended into China proper. Americans and Western Europeans working or having interests there worried that the local people would rise up and resist the foreign presence. This fear became a reality in 1900 when a Chinese religious movement, the Yihequan (Righteous and Harmonious Fists), started to kill Christian missionaries and other foreigners in an effort to drive them out of their homeland because they had grown tired of being treated as second-class citizens in their own country, and they resented the taint of Christianity on their culture. Their use of ritual martial arts prompted Westerners to call them the Boxers and term their uprising the Boxer Rebellion. While a coalition of European powers plus America and Japan made short work of this “insurrection,” the dread of it happening on a larger scale led to the creation of the Fu Manchu character by British writer Sax Rohmer.

This Chinese criminal mastermind embodied the characteristics of what the English feared most: a Chinese who understood and used Western technology and who could successfully lead his people in conquest against the British Empire. Within a few pages of the first story, “The Mystery of Fu Manchu,” the protagonist, British agent Sir Denis Nayland Smith, tells the story’s narrator he needs to stop a plot that threatens the existence of the entire white race. For all his racial “superiority,” however, Smith never catches or kills Fu Manchu in any of the books and shorter works.

In the year of the Boxer Rebellion, China controlled an area of 4,460,000 square miles and had a population of about four million. A 1907 article that appeared in The North American Review predicted the Mongolian race (usually meant to include the Chinese, Japanese, Koreans and ethnic Mongolians) would make up one-third of the world’s population in the near future, and went on to outline the terrible things that could happen to the West if left unchecked. It did not matter whether the article’s statistics had any validity. Just appearing in a magazine as prominent as The North American Review made them as good as true. (According to The World Almanac and Encyclopedia 1912, the total world population stood at 1,520,150,000. Of this, East Asians made up 630,000,000 and whites 625,000,000, meaning the former consisted of about 40 percent of the total population and the latter 41 percent, hardly the disparity the Yellow Peril alarmists would have liked people to believe.) Japan’s stunning 1905 victory over Russia in the Russo-Japanese War only served to heighten the fears of the

Yellow Peril because until this moment no modern Western power had ever suffered a defeat from an Far Eastern nation. The triumph had taken the West off guard in large part because only fifty-two years earlier, Japanese society still clung to its feudal, agrarian past. Since its borders had remained closed to most outsiders, the West knew little of it or its people until 1853 when Commodore Matthew C. Perry of the U.S. Navy arrived with his squadron of modern warships to force it to open up trade. The Japanese, technologically outmatched, reluctantly acquiesced. Perry irreversibly changed Japanese culture and government on a scale similar to Nicolaus Copernicus’ revelation that the Earth rotated around the Sun or Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. Within a generation of Perry’s arrival, the Japanese emperor—with the help if not the pressure of his advisors—established a parliamentary system of government, eliminated the rigid class system, and replaced the samurai with a modern conscription army. The country began the process of industrialization and formed a modern navy.

Japan feared European powers would takeover its islands in a way similar to what they had done to China, so it decided to establish an empire of its own to serve as a buffer zone against this. To that end, it gained control of Formosa and Korea after fighting a brief war with China in 1894–1895 (the incident that had prompted the Kaiser to produce his cartoon), then went to war with Russia in 1904 to wrest from it control of the Liaotung Peninsula, an important piece of real estate because it granted easy access into the rest of Manchuria.

Jack London, having witnessed the Russo-Japanese War as a reporter, did not like what he had seen. In 1904, he published an essay about the subject titled “The Yellow Peril.” It began by praising the resilience of the Chinese and offered a hardy admiration of their capacity to continue their day to day lives despite war all around them as well as their ability and willingness to embrace new ideas brought in from the West. Americans, London decided, had nothing to fear from the Chinese because their government kept them submissive and subservient. The Japanese, on the other hand, had proved themselves both aggressive and adept war makers. London warned that if Japan ever took control of the Chinese and directed them to make war, their population of 400 million could readily overwhelm the West.

London followed this notion up in his 1910 short story “The Unparalleled Invasion.” Set in 1976, this near-future war tale tells the “history” of the world after the Japanese triumph over Russia in 1905. The Japanese do indeed try to harness the power of the Chinese as London predicted in his essay, but the attempt fails and leads to Japan’s ruin. Following this, China awakens and becomes a major industrial power. Rather than outright conquer other nations, the Chinese government sends overwhelming numbers of colonists into those places it wants. When an external Chinese militia invades, the Chinese colonists rise up to make conquest quick and easy (the fifth column theme). Alarmed, European nations try and fail to do something about it. France, for example, sends into China an army of a quarter of a million men, but before this force reaches Beijing, the massive Chinese population swallows it up, leaving no survivors.

In desperation, the Western nations form a great alliance and commit themselves to a new plan. They blockade China with their armies and navies but make no move to invade. Then they fly airplanes overhead to drop glass vials filled with an unidentified liquid, in truth a vector filled with a number of deadly communicable diseases such as smallpox and the Bubonic Plague. The resulting pestilence kills about three-fourths of the Chinese population. When survivors try to flee China’s borders, the West’s army and naval blockade kills them. With the Chinese out of the way, the allies take the land for themselves. Sadly, this horrific ending of purposeful genocide elicited no outcry against London; rather, it presented the West with a glimmer of hope as to how it might one day deal with the Yellow Peril.

In the decade when London wrote his essay and short story, Japan posed little risk to the rest of the world. While it certainly had the potential to become a significant commercial rival and its modern military could execute conquests, it lacked the resources and population to prevent a determined Western nation from defeating it, as World War II showed. The dropping of the atomic bombs did nothing more than elicit a quicker surrender than might have otherwise occurred. By the time America used them, Japan had already lost the war, having run out of men, fuel, and matériel to continue a realistic defense.

During World War I, Japan had fought on the side of the Allies in exchange for some minor territorial gains. In the decade thereafter, it showed little inclination for financial or military aggression. During the 1920s, its economy slugged along. Militarily, it grudgingly agreed to several unequal naval treaties in 1921 and 1922 that, among other stipulations, committed it to keeping its navy proportionally smaller than the Western signatories. For the rest of the decade, it did not embark on any significant military adventures.

All this changed in October 1929. Like Perry’s arrival in the mid-nineteenth century, the Great Depression irrevocably altered Japan’s economy, government, and national mentality. It caused the already fragile Japanese economy to collapse, throwing millions out of work. When the Japanese government agreed in 1930 to renew its unequal treaties with the Western powers, an upset military officer feeling betrayed shot the Japanese prime minister, who died the next year. Throughout the rest of the 1930s, all of Japan’s prime ministers save for one came from the military. A feeling of intense nationalism coincided with this. The Japanese government reinvigorated its ruined economy with massive expenditures in public works and to the military, the latter of which received three-fourths of total spending.

In the decade when London wrote his essay and short story, Japan posed little risk to the rest of the world. While it certainly had the potential to become a significant commercial rival and its modern military could execute conquests, it lacked the resources and population to prevent a determined Western nation from defeating it, as World War II showed. The dropping of the atomic bombs did nothing more than elicit a quicker surrender than might have otherwise occurred. By the time America used them, Japan had already lost the war, having run out of men, fuel, and matériel to continue a realistic defense.

During World War I, Japan had fought on the side of the Allies in exchange for some minor territorial gains. In the decade thereafter, it showed little inclination for financial or military aggression. During the 1920s, its economy slugged along. Militarily, it grudgingly agreed to several unequal naval treaties in 1921 and 1922 that, among other stipulations, committed it to keeping its navy proportionally smaller than the Western signatories. For the rest of the decade, it did not embark on any significant military adventures.

All this changed in October 1929. Like Perry’s arrival in the mid-nineteenth century, the Great Depression irrevocably altered Japan’s economy, government, and national mentality. It caused the already fragile Japanese economy to collapse, throwing millions out of work. When the Japanese government agreed in 1930 to renew its unequal treaties with the Western powers, an upset military officer feeling betrayed shot the Japanese prime minister, who died the next year. Throughout the rest of the 1930s, all of Japan’s prime ministers save for one came from the military. A feeling of intense nationalism coincided with this. The Japanese government reinvigorated its ruined economy with massive expenditures in public works and to the military, the latter of which received three-fourths of total spending.

One Japanese military officer, Lieutenant Colonel Ishiwara Kanji, became an avid student of prophetic Buddhist texts. Convinced by them that Japan would soon enter an apocalyptic war, he decided to help the process along. While stationed in Manchuria, he led a bombing raid on the South Manchurian Railway on the night of September 18, 1931, and blamed it on Chinese rebels. To convince Tokyo that Chinese insurgents posed an imminent danger to Japanese colonists living in Manchuria, he launched a second attack, this one in the city of Jilin. As he had hoped, Tokyo reacted with a drastic measure. On February 15, 1932, it designated Manchuria as the independent state of Manchukuo. This restructuring had an Orwellian twist as the change accorded Japan more control over the area, not less. To give this new “nation” a whiff of legitimacy, Tokyo made the last Chinese Manchu emperor its token head. In 1937, Chiang Kai-shek, head of the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang), moved troops into Beijing in defiance of a Sino-Japanese treaty, giving Japan the excuse it needed to declare war on China and thus expand its territory beyond Manchukuo.

Japan’s aggression strained its deteriorating relation with America, a process already aggravated by the 1924 immigration law that excluded all Japanese from emigrating to the United States. Those Japanese who had settled in America before 1924 found themselves increasingly under attack thereafter. Once again, jealousy more than anything else played a part in this. Despite the Depression, Japanese-Americans had done well for themselves. American newspapers, particularly those published by the Hearst company, fueled this discontent by running frequent anti-Japanese stories.

White animosity against them gave politicians, especially those in the Pacific states, an issue for which they could gain votes. In California, legislators passed draconian laws to make the lives of resident Japanese difficult. One made it harder for them to own and operate fishing boats. Another stipulated that all newspapers had to publish at least 20 percent of their copy in English, a statute meant to shutter Japanese-language newspapers published in the state. Fears of a Japanese fifth column in American also cropped up at this time, an idea well known thanks to the plethora of near-future Yellow Peril war scenarios. While a belief in a Japanese fifth column might have aroused the ire of the American public, it had little basis in reality. The Japanese population never exceeded 300,000. Japanese had only begun to settle in America en masse in the 1890s, a process that stopped in 1924 with the U.S. immigration legislation that outright banned them from settling in the United States.

Japan’s aggression strained its deteriorating relation with America, a process already aggravated by the 1924 immigration law that excluded all Japanese from emigrating to the United States. Those Japanese who had settled in America before 1924 found themselves increasingly under attack thereafter. Once again, jealousy more than anything else played a part in this. Despite the Depression, Japanese-Americans had done well for themselves. American newspapers, particularly those published by the Hearst company, fueled this discontent by running frequent anti-Japanese stories.

White animosity against them gave politicians, especially those in the Pacific states, an issue for which they could gain votes. In California, legislators passed draconian laws to make the lives of resident Japanese difficult. One made it harder for them to own and operate fishing boats. Another stipulated that all newspapers had to publish at least 20 percent of their copy in English, a statute meant to shutter Japanese-language newspapers published in the state. Fears of a Japanese fifth column in American also cropped up at this time, an idea well known thanks to the plethora of near-future Yellow Peril war scenarios. While a belief in a Japanese fifth column might have aroused the ire of the American public, it had little basis in reality. The Japanese population never exceeded 300,000. Japanese had only begun to settle in America en masse in the 1890s, a process that stopped in 1924 with the U.S. immigration legislation that outright banned them from settling in the United States.

In 1928, Philip Nowlan tapped into this newest spate of anti-Japanese Yellow Perilism as well as more traditional aspects of the anti-Chinese variety with his short story “Armageddon 2419 a.d.” Appearing in the August 1928 issue of the pulp magazine Amazing Stories, it introduced the character of Anthony Rogers, a twentieth century man who falls into suspended animation after being trapped in an abandoned mine and exposed to radioactive gases. When he awakes in 2419, he finds America overrun by the Han, a Chinese-like race who had accomplished their conquest by use of a disintegration ray. The Americans invent an even more powerful weapon, the rocket gun, which they use to defeat their enemy regionally with plans to free all of America, a feat effected in the story’s sequel, “The Airlords of Han.” In this latter tale, the Americans annihilate the Han (possibly Tibetans who interbred with space aliens) in an act of wanton genocide.

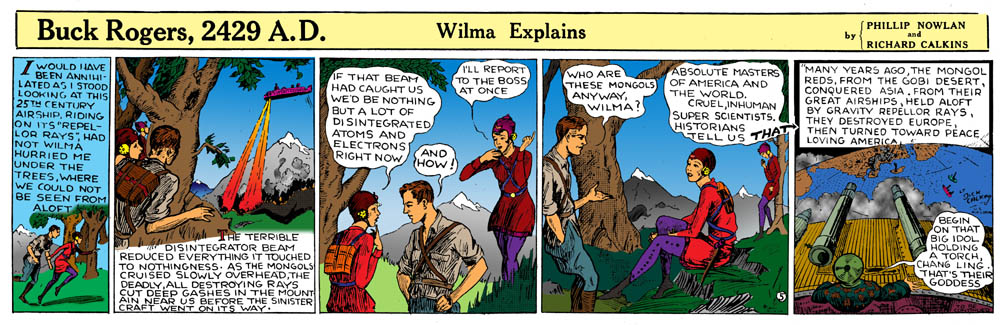

John Flint Dille, owner of National Newspaper Syndicate, liked the first story so much he asked Nowlan to write a comic strip version. When Nowlan agreed, Dille brought in one of his staff cartoonists, Richard W. Calkins, to draw it. Dille decided the character needed a catchier name, so he changed it to Buck after Buck Jones, a popular movie cowboy actor of the day. Buck Rogers, 2429 a.d. (the year changed annually to make it 500 years after the contemporary one) first appeared in newspapers on January 7, 1929.

Beyond the main character’s name change, the strip differed from the short story that inspired it in other ways, including the fact that the Han became the Mongols, who appeared as stereotypical Chinese, moustaches and all. The debut strip has Buck awakening to find his soon-to-be-girlfriend, Wilma, fighting “half-breeds,” presumably Americans who had intermixed with the Mongols. Wilma calls the Mongols “absolute masters of America and the world. Cruel, inhuman super scientists. Historians tell us that many years ago, the Mongol Reds, from the Gobi Desert, conquered Asia. From their great airships, held aloft by gravity repellor rays, they destroyed Europe, then turned toward peace loving America.” She explains that after the conquest, all but a few Americans fell into a state of barbarism. Those who had not, the scientists, spent their time creating technologies that could defeat the Mongols.

Early on in the series, the Mongols capture Wilma. When the emperor sees her via television (one of the many pieces of science that made the strip ahead of its time), he immediately falls in love with her. She escapes, suffers recapture, and finally gets away when Buck rescues her. The emperor, still in love, orders his people to bring her to him, which they do. He wants to make her his “favorite,” certainly a coded way of saying he desired her to become his main concubine. She rejects him and escapes soon thereafter. Here writer Nowlan had tapped into one of dominant themes of the Yellow Peril: the fear that the “white” and “yellow” races would intermix and reproduce, creating those dreaded “half-breeds” who appeared in the debut Buck Rogers’ strip.

The next major storyline has Rogers meeting a secret society of Mongols intent on overthrowing their emperor. The Americans unofficially ally themselves with these dissidents in a plot to capture the emperor, an effort led by Rogers. Upon his success, he forces the emperor to make peace, thus saving America from the ever-present Mongol menace—the stand-in for the Yellow Peril. Nowlan used this conclusion of hostilities to launch Rogers into space and other-worldly adventures. Although Nowlan died in February 1940, the strip continued. It returned to the Yellow Peril theme once more with the onset of World War II. Buck’s newest enemies became the descendents of those who had planned Pearl Harbor.

Buck Rogers reached a much wider audience than a novel or short story could have in that era because it appeared in newspapers, which at the time had a massive readership that included people with no interest in the Yellow Peril or science fiction. In 1935, for example, newspaper dailies had approximately 40,871,000 readers a day. At the height of its popularity, the Buck Rogers strip ran in 287 papers and spawned a popular radio program starting in 1932 and a movie serial produced by Universal in 1939. Therefore people who would never have considered picking up a copy of Amazing Stories or one of H.G. Well’s science fiction novels might still have read the adventures of Buck Rogers just because they happened upon him as they looked to see if their horse won its race the previous day.

Buck Rogers’ success prompted many imitators, the best of which, Flash Gordon, appeared in 1933 and came from United King Features. Written and drawn by the talented Alex Raymond, this Sunday strip had three main protagonists who traveled to the planet of Mongo to stop its dictator, Ming the Merciless, from destroying the Earth. It takes little to figure out the strip’s real meaning. Mongo clearly represents Mongolia, the generic residence for most East Asians. Ming himself, aside from sharing his name with the Chinese dynasty most famous for its vases, looks uncannily similar to Fu Manchu, as do his henchmen. One of Flash’s companions, fellow Earthman Dr. Hans Zarkov, uses advanced scientific breakthroughs to help Flash defeat Ming.

This use of super science to end a major conflict became a reality in 1945 when America dropped two atomic bombs on Japan. Government and military censorship had kept Americans blissfully ignorant of the bombs’ terrible effects on the Japanese people both in terms of explosive damage and the ill effects of radiation, but this ended about a year later with the with the publication of journalist John Hershey’s article “Hiroshima,” which appeared in the August 31, 1946, issue of The New Yorker. This famous piece outlined the grisly details of the effect of the bombs on Japan and its people. Despite this, public outcry did not ensue. In his scholarly article “From the Yellow Peril to Japanese Wasteland: John Hershey’s ‘Hiroshima,’” Patrick B. Sharp argued that Buck Rogers, Flash Gordon, and the entire future-war Yellow Peril genre made the dropping of the atomic bombs easier for Americans to accept because they had read so many stories that had just this type of catastrophic end. Since they all used super science solution to defeat the Yellow Peril, this had conditioned the American masses to accept the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as a matter of course and never mind the horror they had caused.🕜

John Flint Dille, owner of National Newspaper Syndicate, liked the first story so much he asked Nowlan to write a comic strip version. When Nowlan agreed, Dille brought in one of his staff cartoonists, Richard W. Calkins, to draw it. Dille decided the character needed a catchier name, so he changed it to Buck after Buck Jones, a popular movie cowboy actor of the day. Buck Rogers, 2429 a.d. (the year changed annually to make it 500 years after the contemporary one) first appeared in newspapers on January 7, 1929.

Beyond the main character’s name change, the strip differed from the short story that inspired it in other ways, including the fact that the Han became the Mongols, who appeared as stereotypical Chinese, moustaches and all. The debut strip has Buck awakening to find his soon-to-be-girlfriend, Wilma, fighting “half-breeds,” presumably Americans who had intermixed with the Mongols. Wilma calls the Mongols “absolute masters of America and the world. Cruel, inhuman super scientists. Historians tell us that many years ago, the Mongol Reds, from the Gobi Desert, conquered Asia. From their great airships, held aloft by gravity repellor rays, they destroyed Europe, then turned toward peace loving America.” She explains that after the conquest, all but a few Americans fell into a state of barbarism. Those who had not, the scientists, spent their time creating technologies that could defeat the Mongols.

Early on in the series, the Mongols capture Wilma. When the emperor sees her via television (one of the many pieces of science that made the strip ahead of its time), he immediately falls in love with her. She escapes, suffers recapture, and finally gets away when Buck rescues her. The emperor, still in love, orders his people to bring her to him, which they do. He wants to make her his “favorite,” certainly a coded way of saying he desired her to become his main concubine. She rejects him and escapes soon thereafter. Here writer Nowlan had tapped into one of dominant themes of the Yellow Peril: the fear that the “white” and “yellow” races would intermix and reproduce, creating those dreaded “half-breeds” who appeared in the debut Buck Rogers’ strip.

The next major storyline has Rogers meeting a secret society of Mongols intent on overthrowing their emperor. The Americans unofficially ally themselves with these dissidents in a plot to capture the emperor, an effort led by Rogers. Upon his success, he forces the emperor to make peace, thus saving America from the ever-present Mongol menace—the stand-in for the Yellow Peril. Nowlan used this conclusion of hostilities to launch Rogers into space and other-worldly adventures. Although Nowlan died in February 1940, the strip continued. It returned to the Yellow Peril theme once more with the onset of World War II. Buck’s newest enemies became the descendents of those who had planned Pearl Harbor.

Buck Rogers reached a much wider audience than a novel or short story could have in that era because it appeared in newspapers, which at the time had a massive readership that included people with no interest in the Yellow Peril or science fiction. In 1935, for example, newspaper dailies had approximately 40,871,000 readers a day. At the height of its popularity, the Buck Rogers strip ran in 287 papers and spawned a popular radio program starting in 1932 and a movie serial produced by Universal in 1939. Therefore people who would never have considered picking up a copy of Amazing Stories or one of H.G. Well’s science fiction novels might still have read the adventures of Buck Rogers just because they happened upon him as they looked to see if their horse won its race the previous day.

Buck Rogers’ success prompted many imitators, the best of which, Flash Gordon, appeared in 1933 and came from United King Features. Written and drawn by the talented Alex Raymond, this Sunday strip had three main protagonists who traveled to the planet of Mongo to stop its dictator, Ming the Merciless, from destroying the Earth. It takes little to figure out the strip’s real meaning. Mongo clearly represents Mongolia, the generic residence for most East Asians. Ming himself, aside from sharing his name with the Chinese dynasty most famous for its vases, looks uncannily similar to Fu Manchu, as do his henchmen. One of Flash’s companions, fellow Earthman Dr. Hans Zarkov, uses advanced scientific breakthroughs to help Flash defeat Ming.

This use of super science to end a major conflict became a reality in 1945 when America dropped two atomic bombs on Japan. Government and military censorship had kept Americans blissfully ignorant of the bombs’ terrible effects on the Japanese people both in terms of explosive damage and the ill effects of radiation, but this ended about a year later with the with the publication of journalist John Hershey’s article “Hiroshima,” which appeared in the August 31, 1946, issue of The New Yorker. This famous piece outlined the grisly details of the effect of the bombs on Japan and its people. Despite this, public outcry did not ensue. In his scholarly article “From the Yellow Peril to Japanese Wasteland: John Hershey’s ‘Hiroshima,’” Patrick B. Sharp argued that Buck Rogers, Flash Gordon, and the entire future-war Yellow Peril genre made the dropping of the atomic bombs easier for Americans to accept because they had read so many stories that had just this type of catastrophic end. Since they all used super science solution to defeat the Yellow Peril, this had conditioned the American masses to accept the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as a matter of course and never mind the horror they had caused.🕜

The Valkyries symbolized the nations of France, Russia, Germany, Italy, Austria and England. The fire around the Buddha represented the burning of Europe by the Japanese and other East Asian people. The cross above stood for Christianity, and the angel warned, “nations of europe! join in the defense of your faith and your home!” The Kaiser had produced the picture in reaction to Japan’s victory over China the year before in which Japan won control of Korea and Formosa (modern Taiwan). The Kaiser worried that the East—either China or Japan or both—would rise up and take over the world if Europe did not unite and do something about it, a fear known as the “Yellow Peril.”

The European dread of a hoard from the East may go back as far as the Greeks, who for a time worried about a Persian invasion, or perhaps it arose from a lingering memory over the spectacular inroads into Europe made by the Huns and Mongols. During the Dark and Middle Ages, ignorance of the East lessened this anxiety. In those eras, Europeans had no idea what lay east beyond India, itself a vaguely defined place in which monstrous races such as centaurs, dog-headed men known as Cynocephali, Pygmies and Amazons lurked. When Europeans reached China during the early years of the Age of Exploration, that empire either turned away or chased them out because it had closed its borders to most foreigners.

The European dread of a hoard from the East may go back as far as the Greeks, who for a time worried about a Persian invasion, or perhaps it arose from a lingering memory over the spectacular inroads into Europe made by the Huns and Mongols. During the Dark and Middle Ages, ignorance of the East lessened this anxiety. In those eras, Europeans had no idea what lay east beyond India, itself a vaguely defined place in which monstrous races such as centaurs, dog-headed men known as Cynocephali, Pygmies and Amazons lurked. When Europeans reached China during the early years of the Age of Exploration, that empire either turned away or chased them out because it had closed its borders to most foreigners.