Carollin Historical Park

Carillon Historical Park

Entrance

Deeds Carillon

William Morris House

Newcom Tavern

I did a Google search to see if there were a museum dedicated to the Wright Brothers, and, sure enough, three hours from where I live, I found the Wright Brothers National Museum in Dayton, Ohio, which is at Carillon Historical Park (CHP), a place I’d never heard of. Deciding to make a day of it, I along with two traveling companions headed out early one morning to visit. From what I saw on CHP’s website I knew it might be somewhat extensive—thus the early start to get there—but I had no idea just how big it is.

Covering sixty-five acres, CHP is a gem every history lover capable of making the pilgrimage really must visit! On the day we went there, about six to eight buildings were closed for renovation, and it still took us four hours to see everything. The park is constantly updating itself. It was at the beginning stages of constructing a full size railroad track that will circle the park to allow a train to run on it.

While parking, we noticed some sort of tower nearby. After getting out of the car, we walked towards it and saw it had a series of bells, so we figured it was a run-of-the-mill bell tower. Except it’s far more. It’s a carillon, which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as “a set of bells so hung and arranged as to be capable of being played upon either by manual action or by machinery” and “an air or melody played on the bells.” The park, which opened in 1950, was founded by Dayton industrialist and philanthropist Colonel Edward Deeds. While in Belgium, his wife, Edith, so enjoyed carillon music that she wanted to bring it Dayton. So her and her husband had a carillon built.

Covering sixty-five acres, CHP is a gem every history lover capable of making the pilgrimage really must visit! On the day we went there, about six to eight buildings were closed for renovation, and it still took us four hours to see everything. The park is constantly updating itself. It was at the beginning stages of constructing a full size railroad track that will circle the park to allow a train to run on it.

While parking, we noticed some sort of tower nearby. After getting out of the car, we walked towards it and saw it had a series of bells, so we figured it was a run-of-the-mill bell tower. Except it’s far more. It’s a carillon, which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as “a set of bells so hung and arranged as to be capable of being played upon either by manual action or by machinery” and “an air or melody played on the bells.” The park, which opened in 1950, was founded by Dayton industrialist and philanthropist Colonel Edward Deeds. While in Belgium, his wife, Edith, so enjoyed carillon music that she wanted to bring it Dayton. So her and her husband had a carillon built.

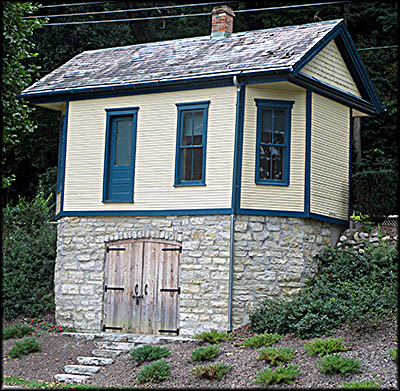

CHP contains a hodgepodge of historical buildings, most from Dayton or the surrounding area. Some are originals, others replicas. Two historic buildings of note are the William Morris House and the Newcom Tavern, which are conveniently beside one another. The former was built 1815 in Centerville, Ohio, by William Morris, a veteran of the Revolutionary War who started a farm in Ohio. The latter was built for George Newcomer between 1796 and 1799 to serve downtown Dayton. The first half constructed as a home for Newcomer and his family, and the other half, built later, to serve as a tavern. This was also used at different times as a jail, general store, church, and court house.

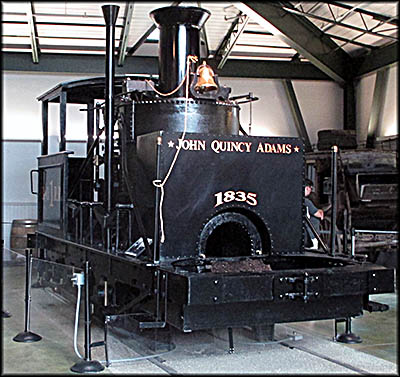

CHP has purpose-built buildings dedicated to specific themes, such as the James F. Dicke Family Transportation Center. This houses, among other things, a trolley, prairie schooner, Conestoga wagon, and the John Quincy Adams—a steam engine built in Baltimore for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. It’s the last one in existence of its type. When Edward Deeds went looking for a steam locomotive for his museum and learned this one was one the scrap heap, he bought and restored it. The city of Baltimore wasn’t happy upon learning that a rare historic artifact (of which it probably had no knowledge) had been snatched from it.

The tour of the Wright Brothers National Museum starts in the Wright Cycle Company building, which is a replica because the original is in Greenfield Village. It was here that Orville and Wilbur Wright designed their first three airplanes. Previous to getting into the bicycle business, the Wrights started and ran the print shop Wright & Wright Job Printers, and some of what they produced, including the newspapers they published, can be seen here. It was only later during the bike craze of the 1890s that they opened a bike shop. They never owned any of the buildings in which they operated, and they moved when the opportunity of a better space and lower rent presented itself. When the Wrights moved into this particular building, which was once located at Dayton’s 1127 West Third Street, they brought into it both their print and bike shops and occupied it from 1897 to 1916, staying after getting out of the bike business in 1908.

CHP has purpose-built buildings dedicated to specific themes, such as the James F. Dicke Family Transportation Center. This houses, among other things, a trolley, prairie schooner, Conestoga wagon, and the John Quincy Adams—a steam engine built in Baltimore for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. It’s the last one in existence of its type. When Edward Deeds went looking for a steam locomotive for his museum and learned this one was one the scrap heap, he bought and restored it. The city of Baltimore wasn’t happy upon learning that a rare historic artifact (of which it probably had no knowledge) had been snatched from it.

The tour of the Wright Brothers National Museum starts in the Wright Cycle Company building, which is a replica because the original is in Greenfield Village. It was here that Orville and Wilbur Wright designed their first three airplanes. Previous to getting into the bicycle business, the Wrights started and ran the print shop Wright & Wright Job Printers, and some of what they produced, including the newspapers they published, can be seen here. It was only later during the bike craze of the 1890s that they opened a bike shop. They never owned any of the buildings in which they operated, and they moved when the opportunity of a better space and lower rent presented itself. When the Wrights moved into this particular building, which was once located at Dayton’s 1127 West Third Street, they brought into it both their print and bike shops and occupied it from 1897 to 1916, staying after getting out of the bike business in 1908.

Both Wrights were enthusiastic cyclists, and in 1892 they opened Wright Cycle Exchange. In 1897, they started building their own bikes, the Van Cleve and St. Clair, selling 95 of the former and 77 of the latter. If you have one, you’ve got a very valuable artifact because few have survived to the present day. Bicycle design, construction and repair required a person to learn quite a few skills, including metal working, woodworking, and an understanding of gears and chain-driven power. All these proficiencies would serve the Wrights well during their journey to build their first powered aircraft.

Orville and Wilbur are said to have been inspired to fly by a toy helicopter given to them by their father, but many others with the same idea came before them. In 1010 ce, a monk named Oliver of Malmesbury put on artificial wings, jumped off Malmesbury Abbey, and went a grand total of 125 paces before plunging to the ground and breaking both legs. The same museum information sign from which that bit of information came also noted that “a man in Constantinople [Istanbul], Turkey, fashioned sail-like wings from a fabric gathered into pleats and folds. He fell down from the top of a tower and died.” Otto Lilienthal flew manned gliders from 1891 to 1896 until a crash in one killed him.

As the Wrights developed their first planes, they did so in secret but also made sure to document their work with both witnesses and photographs. In 1902 they bought a Korono V camera, and it’s this one that captured the first successful powered manned flight. The camera can be seen on display in the museum. This was prudent of them considering all the patent fights they’d later get into where they had to prove they were the first to successfully fly a powered aircraft on December 17, 1903.

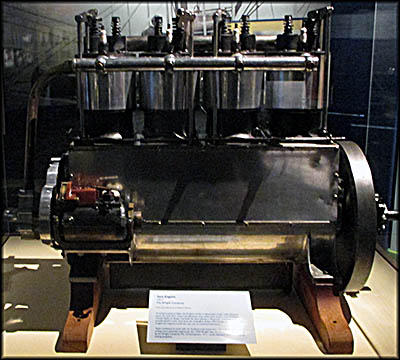

For them, this monumental day was just a start. They had no intention of commercializing their idea until they could make a plane that could not just get in into the air, but stay there for a useful amount of time. They spent the next few years building new flyers with modifications to address problems they encountered. Needing more power, they had one of their employees build them a more powerful engine. They created separate levers for rudder and wing warping, designed a catapult to launch their plane, and redesigned the propeller to make it more efficient. Some of the parts were tested in the wind tunnel they constructed in their bike shop.

Orville and Wilbur are said to have been inspired to fly by a toy helicopter given to them by their father, but many others with the same idea came before them. In 1010 ce, a monk named Oliver of Malmesbury put on artificial wings, jumped off Malmesbury Abbey, and went a grand total of 125 paces before plunging to the ground and breaking both legs. The same museum information sign from which that bit of information came also noted that “a man in Constantinople [Istanbul], Turkey, fashioned sail-like wings from a fabric gathered into pleats and folds. He fell down from the top of a tower and died.” Otto Lilienthal flew manned gliders from 1891 to 1896 until a crash in one killed him.

As the Wrights developed their first planes, they did so in secret but also made sure to document their work with both witnesses and photographs. In 1902 they bought a Korono V camera, and it’s this one that captured the first successful powered manned flight. The camera can be seen on display in the museum. This was prudent of them considering all the patent fights they’d later get into where they had to prove they were the first to successfully fly a powered aircraft on December 17, 1903.

For them, this monumental day was just a start. They had no intention of commercializing their idea until they could make a plane that could not just get in into the air, but stay there for a useful amount of time. They spent the next few years building new flyers with modifications to address problems they encountered. Needing more power, they had one of their employees build them a more powerful engine. They created separate levers for rudder and wing warping, designed a catapult to launch their plane, and redesigned the propeller to make it more efficient. Some of the parts were tested in the wind tunnel they constructed in their bike shop.

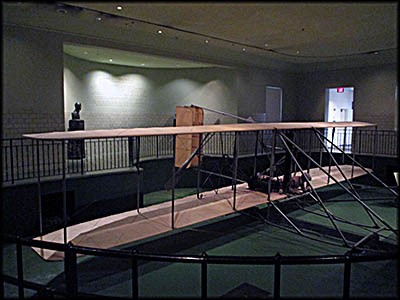

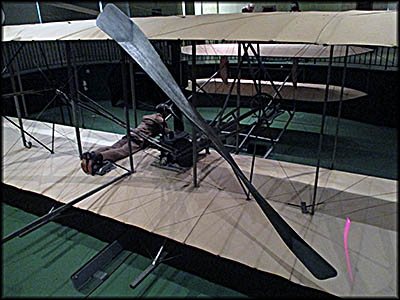

The 1905 Wright Flyer III was the world’s first practical airplane that could get into the air, stay there, and remain under full control of the pilot. It’s in the museum and was an impressive piece of engineering for its time. It was the Wrights’ last test plane and the one that they’d use as the basis for their commercial model. After perfecting it, they stopped flying until 1908 when Wilbur headed to Europe to secure funding, and Orville demonstrated the plane for the U.S. Army.

On September 17, 1908, while doing this at Fort Meyer, Virginia, Orville and passenger Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge crashed. Selfridge died—history’s first airplane fatality—and Orville would suffer chronic back issues for the rest of his life. In 1908, the Army decided to purchase a plane only if it met exacting standards, including the ability to take off under its own power without the use of a catapult as well as having an upright seat. The Wrights made these modifications and sold their plane to the Army in 1909.

Not far from the exit point of the Wright’s museum is Smith Covered Bridge. I can’t resist walking over any bridge that presents itself, especially covered ones, so I made a beeline to it. This particular one was built in the Smith Bridge Company from Toledo, Ohio, and it once spanned the Little Sugar Creek close to Bellbrook, Ohio, on Feedwire Road. So excited was I to walk onto the bridge that I missed the sign above its entrance, which one of my traveling companions pointed out to me. It read: “$5 FINE FOR RIDING OR DRIVING OVER THIS BRIDGE FASTER THAN A WALK. $20 FINE FOR DRIVING OVER THIS BRIDGE MORE THAN 20 HORSES OR CATTLE AT ONCE. $5 FINE FOR CARRYING FIRE OVER OR UNDER THIS BRIDGE IN AN UNCLOSED VESSEL.”

On September 17, 1908, while doing this at Fort Meyer, Virginia, Orville and passenger Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge crashed. Selfridge died—history’s first airplane fatality—and Orville would suffer chronic back issues for the rest of his life. In 1908, the Army decided to purchase a plane only if it met exacting standards, including the ability to take off under its own power without the use of a catapult as well as having an upright seat. The Wrights made these modifications and sold their plane to the Army in 1909.

Not far from the exit point of the Wright’s museum is Smith Covered Bridge. I can’t resist walking over any bridge that presents itself, especially covered ones, so I made a beeline to it. This particular one was built in the Smith Bridge Company from Toledo, Ohio, and it once spanned the Little Sugar Creek close to Bellbrook, Ohio, on Feedwire Road. So excited was I to walk onto the bridge that I missed the sign above its entrance, which one of my traveling companions pointed out to me. It read: “$5 FINE FOR RIDING OR DRIVING OVER THIS BRIDGE FASTER THAN A WALK. $20 FINE FOR DRIVING OVER THIS BRIDGE MORE THAN 20 HORSES OR CATTLE AT ONCE. $5 FINE FOR CARRYING FIRE OVER OR UNDER THIS BRIDGE IN AN UNCLOSED VESSEL.”

Just beyond the bridge is Lock No. 17 from the Miami and Erie Canal, which opened in 1829 and initially connected Cincinnati and Dayton, then extended to Toledo. Even though the lock looks as if it’s always been there, it was moved to CHP from Huber Heights, which is just north of Dayton. Beside it is a canal superintendent’s office in which tolls were collected. And just beyond that is the Morrison Iron Bridge, which was built in 1881 and once served Farmersville, Ohio.

On its other side looms a high tower with a clock at its top. This is the Callahan Building Clock, which was originally part of Dayton’s first skyscraper, a nine story edifice built in 1892 by banker and manufacturer William P. Callahan. Daytonians wanted a public clock, so a few years Callahan had one installed. When three more stories were added to the building, the old clock was removed, but public outcry prompted one building tenant, City National Bank, to fund a new illuminated clock. When the Callahan Building—renamed Gem City Savings Building—was torn down in 1977, the clock was moved to the Reynolds & Reynolds building. When that was demolished in 2006, the clock found a home at CHS.

It now sets atop of the Brethren Tower. One hundred feet tall, you can climb to the top, but only if you want to suffer terrible disappointment. There I saw one of the most uninspired views I’ve gazed upon. Mounted binoculars are free to use, but unless you want to look at hotel room windows, a freeway or the top of some trees, don’t bother. I climbed it so you don’t have to, and have provided a photo of the best view I saw, such as it was.

Dayton was once home to many industries including one most reader will be familiar with from their childhood: Huffy Bikes. You can see a wide variety of past models as well as other antique cycles in the Dayton Cyclery. Huffy Bikes started as the Davis Sewing Machine Company. Founded in 1888, it was bought by George P. Huffman and moved to Dayton the next year. There Huffman decided to also make bicycles.

On its other side looms a high tower with a clock at its top. This is the Callahan Building Clock, which was originally part of Dayton’s first skyscraper, a nine story edifice built in 1892 by banker and manufacturer William P. Callahan. Daytonians wanted a public clock, so a few years Callahan had one installed. When three more stories were added to the building, the old clock was removed, but public outcry prompted one building tenant, City National Bank, to fund a new illuminated clock. When the Callahan Building—renamed Gem City Savings Building—was torn down in 1977, the clock was moved to the Reynolds & Reynolds building. When that was demolished in 2006, the clock found a home at CHS.

It now sets atop of the Brethren Tower. One hundred feet tall, you can climb to the top, but only if you want to suffer terrible disappointment. There I saw one of the most uninspired views I’ve gazed upon. Mounted binoculars are free to use, but unless you want to look at hotel room windows, a freeway or the top of some trees, don’t bother. I climbed it so you don’t have to, and have provided a photo of the best view I saw, such as it was.

Dayton was once home to many industries including one most reader will be familiar with from their childhood: Huffy Bikes. You can see a wide variety of past models as well as other antique cycles in the Dayton Cyclery. Huffy Bikes started as the Davis Sewing Machine Company. Founded in 1888, it was bought by George P. Huffman and moved to Dayton the next year. There Huffman decided to also make bicycles.

I was surprised to see a train depot from Bowling Green, Ohio, where I once attended its fine university and lived in that town for a time. The depot itself is in excellent condition but unremarkable for its type. Built in 1895, from here one could get mail, send an receive telegraphs, and board a train. Beyond operating the telegraph and selling tickets, the station master had two levers on hand that, when pulled, activated a green, yellow or red signal to tell a passing train engineer to proceed, proceed with caution, or stop. Train service ended in Bowling Green in 1966.

Of all the considerable number of buildings on the premises, for me the most moving was the Great 1913 Flood Exhibit Building. I knew that Dayton suffered a massive flood in 1913—all of Ohio and much of the Midwest did—but this exhibit made it real in a way reading about it in a book with accompanying photos couldn’t. To understand why Dayton suffered so greatly, let us go back to the city’s founding in 1795 when General James Wilkinson (a Spanish agent who later allied himself the Aaron Burr’s ill-fated attempt to found his own nation), General Arthur St. Clair, Colonel Israel Ludlow, and Jonathan Dayton (who served as the House of Representative’s fourth Speaker and was the youngest person to sign the Constitution) purchased a stretch of land between the Great and Little Miami Rivers. This was a good location because in the fledging United States, water was the best form of transportation.

Other major waterways were nearby. These included Wolf Creek and the Mad and Stillwater Rivers. During the nineteenth century, Dayton suffered from periodic floods, but politicians and government officials hate to do anything that will prevent a future catastrophe because, once averted, it’s hard to take credit for what didn’t happen. So nothing was done expect fixing broken levees and hoping for the best.

As I entered the exhibit, I noticed on a television a man and women were giving a weather forecast. At first I ignored it, figuring it was just weather report from a local channel done recently. Then I realized the woman was wearing an outfit from around 1913. It turned out it’s a forecast explaining the approaching 1913 weather system that would cause the flood. Its rain forecast for Dayton predicted eight to ten inches. Brilliant stuff!

Of all the considerable number of buildings on the premises, for me the most moving was the Great 1913 Flood Exhibit Building. I knew that Dayton suffered a massive flood in 1913—all of Ohio and much of the Midwest did—but this exhibit made it real in a way reading about it in a book with accompanying photos couldn’t. To understand why Dayton suffered so greatly, let us go back to the city’s founding in 1795 when General James Wilkinson (a Spanish agent who later allied himself the Aaron Burr’s ill-fated attempt to found his own nation), General Arthur St. Clair, Colonel Israel Ludlow, and Jonathan Dayton (who served as the House of Representative’s fourth Speaker and was the youngest person to sign the Constitution) purchased a stretch of land between the Great and Little Miami Rivers. This was a good location because in the fledging United States, water was the best form of transportation.

Other major waterways were nearby. These included Wolf Creek and the Mad and Stillwater Rivers. During the nineteenth century, Dayton suffered from periodic floods, but politicians and government officials hate to do anything that will prevent a future catastrophe because, once averted, it’s hard to take credit for what didn’t happen. So nothing was done expect fixing broken levees and hoping for the best.

As I entered the exhibit, I noticed on a television a man and women were giving a weather forecast. At first I ignored it, figuring it was just weather report from a local channel done recently. Then I realized the woman was wearing an outfit from around 1913. It turned out it’s a forecast explaining the approaching 1913 weather system that would cause the flood. Its rain forecast for Dayton predicted eight to ten inches. Brilliant stuff!

The storm that would cause Dayton so much trouble started as heavy snow in the Rocky Mountains. As it moved east, it sparked a number of violent tornados in Nebraska, then Indiana. On March 23—Easter Sunday—it was 66 degrees in Dayton. Rain began that night and winds got as high as forty miles per hour. The storm stalled over the area and dumped rain for the next few days. Some places in the Dayton area received up to eleven inches.

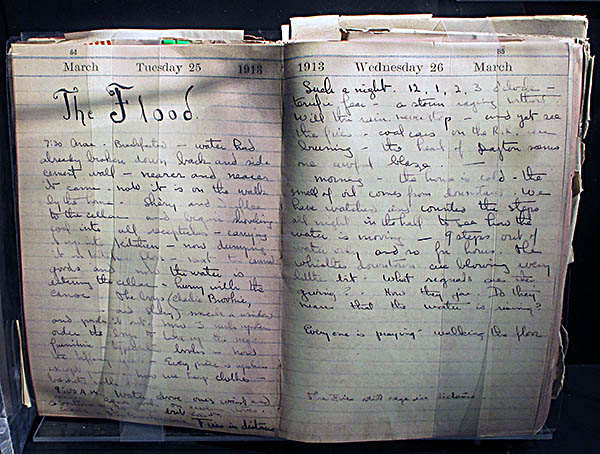

Diary of Katharine Kennedy Brown

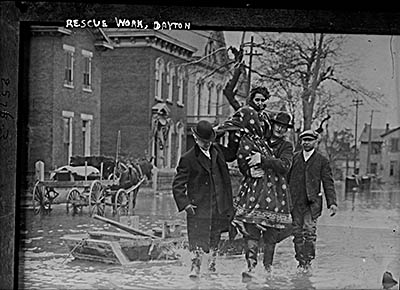

Flooding was expected, but not on the scale that would come. On the morning of March 25, the National Cash Register (NCR) factory blew its whistle to warn Daytonians about the impending flood. Other factories joined the chorus with their whistles, as did churches with their bells. Soon the Great Miami River flowed over its levees. A Mad River levee broke, releasing a ten-foot-high wall of frigid water moving around twenty-five miles per hour that crashed through Dayton and upended anything in its way. The floodwaters kept rising and didn’t crest till 2 a.m. on the morning of March 26. As the flooding worsened, the head of NCR, James H. Patterson, decided to put his employees to work doing disaster relief.

Photos from the 1913 Dayton Flood

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

The flood killed more than 350 people, over 1,400 horses, and about 2,000 small animals. Fourteen thousand homes were destroyed, and $100 million in damage was done. The flood resulted in Grace La Nora’s wedding being postponed. When she finally married at the end of the month, she didn’t get to do so in her handmade wedding dress. It wasn’t until a year later that she finally donned it for a photograph. Possibly the most interesting and powerful artifact in the Great 1913 Flood Exhibit building is the diary of Katharine Kennedy Brown, a firsthand account of how it affected her and Dayton.

After the flooding subsided, Ohio governor James M. Cox declared marital law in Dayton to prevent looting, robbing and thieving. The National Guard came in to help. Dead horses were quickly removed to prevent disease from spreading. Water was pumped out of downtown basements. Mud was cleaned out of houses. Most wooden furniture just fell apart.

Only after experiencing this disaster were the people and politicians of Dayton ready to invest heavily in a flood prevention system. It took just to the end of May to raise the $2 million needed to pay the Morgan Engineering Company from Memphis, Tennessee, to develop a flood control system. In October, the company’s head, Arthur Morgan, presented a plan as well as eight alternatives.

It involved building a series of earthen dams on the Mad, Great Miami, and Stillwater Rivers as well as the Loramie and Twin Creeks. New levees would be erected, bridges raised up, and obstacles that exasperated flooding removed. Governor Cox wholeheartedly supported this plan and got the Ohio Legislature to pass the Vonderheide Act to implement it. Like any good plan, it met strong opposition by those who it would negatively affect. The constitutionality of the Vonderheide Act was put to the test. It was ultimately found constitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court. The Miami Conservancy District was organized in June 1915 and took seven years to complete.🕜

After the flooding subsided, Ohio governor James M. Cox declared marital law in Dayton to prevent looting, robbing and thieving. The National Guard came in to help. Dead horses were quickly removed to prevent disease from spreading. Water was pumped out of downtown basements. Mud was cleaned out of houses. Most wooden furniture just fell apart.

Only after experiencing this disaster were the people and politicians of Dayton ready to invest heavily in a flood prevention system. It took just to the end of May to raise the $2 million needed to pay the Morgan Engineering Company from Memphis, Tennessee, to develop a flood control system. In October, the company’s head, Arthur Morgan, presented a plan as well as eight alternatives.

It involved building a series of earthen dams on the Mad, Great Miami, and Stillwater Rivers as well as the Loramie and Twin Creeks. New levees would be erected, bridges raised up, and obstacles that exasperated flooding removed. Governor Cox wholeheartedly supported this plan and got the Ohio Legislature to pass the Vonderheide Act to implement it. Like any good plan, it met strong opposition by those who it would negatively affect. The constitutionality of the Vonderheide Act was put to the test. It was ultimately found constitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court. The Miami Conservancy District was organized in June 1915 and took seven years to complete.🕜

Prairie Schooner

John Quincy Adams Locomotive

Wright Brothers' Bicycle Shop

Inside the Wright Cyclery

1905 Wright Flyer III

This is a replica of the wind tunnel the Wright Brothers built to test their ideas.

This is a test engine the Wright brothers had an employee build for them.

Smith Covered Bridge

Gristmill

Miami and Erie Canal Lock No. 17

Morrison Iron Bridge

Brethen Tower

View from Brethen Tower

Canal Lock No. 17

When National Cash Register (NCR) moved its headquarters from Dayton to Atlanta, Georgia, it bequeathed its entire collection of historic cash registers to the CHP.