Cleo-Redd Fisher Museum of the Mohican Historical Society

Museum Entrance

Flxible Sidecar

Hotchkiss Gun

Upon entering the Cleo Redd Fisher Museum of the Mohican Historical Society, the first thing I noticed was a Hotchkiss Gun, a gas-powered machine gun designed in 1893 by Austrian cavalryman Adolf Odkolek von Augezd that was used primarily in World War I. My impulse was to take a closer look but I got sidetracked by something odd. No one was around. I called out and made a quick walkthrough of the first floor but not a soul did I find. Seeing a staircase going up, I climbed it and on the second floor found the two Kens. One, Ken Libben, was the museum’s curator, the other a volunteer.

Volunteer Ken did not give a tour per se but he wandered about and stepped in to demonstrate how some of the museum’s artifacts worked, such as the 1927 Reproducto Player-Piano-Organ that was once used to produce music for silent movies in Loudonville’s Ohio Theater. Guided by a paper reel, this self-playing instrument was quite loud and, surprising considering its age, in tune. Another item Ken showed off was a model village made by Walker Lee from nearby Perrysville. Having took twenty years to build, it is filled with moving parts and qualifies as both a mechanical wonder and a work of art.

With this being a family friendly museum, I was surprised to see a Vibro-Life Vibrator on display. It was supposedly used to cure female “hysteria” in the Victorian Age. The accompanying information sign reported, “Hysteria was a ‘catch-all’ diagnosis … caused by a mythical fluid thought to turn poisonous when in the womb for too long … that was originally ‘relieved’ manually by doctors.” Doctors, it went on to say, performed this procedure so often that their fingers cramped, prompting the invention of a mechanical substitute.

This idea first appeared in Rachel Maines’ 1999 book The Technology of Orgasm. Since then it has cropped up in popular culture, documentaries, articles, and books. Although some writers disputed parts of her book, it wasn’t until a 2018 article by Hallie Lieberman and Eric Schatzberg that appeared in the peer-reviewed Journal of Positive Sexuality that Maines’ “hypothesis” (which she insists was no more than this) was thoroughly debunked. They looked at her sources and found them wanting, determining that doctors rarely performed this treatment on women.

Although Loudonville was never a hotbed of industry, in 1913 one of its most successful enterprises, Flxible, was founded by Loudonville native Hugo H. Young, a Harley-Davison dealer, and his partner Carl F. Dudte. Two years earlier Young had invented a much safer motorcycle sidecar with independent suspension that kept it on the ground when the motorcycle turned sharply or negotiated tight curves. Incorporated in 1914, the Flxible Side Car Company capitalized at $25,000. Its first rented factory space in Mansfield had a limited production capacity that stymied the company’s growth.

Enter Charles Kettering. His investment of $160,000 allowed the company to construct a much larger factory in Loudonville from which it was able to build sidecars for sale around the world. During World War I it made them fitted with machine guns, and when the GIs who rode in them came home, they bought their own. The popularity of the Flxible sidecar faded as more people purchased Model Ts. It also didn’t help that in 1925 a national ban on motorcycle sidecar racing was enacted, this having been prompted by a series of accidents.

With this being a family friendly museum, I was surprised to see a Vibro-Life Vibrator on display. It was supposedly used to cure female “hysteria” in the Victorian Age. The accompanying information sign reported, “Hysteria was a ‘catch-all’ diagnosis … caused by a mythical fluid thought to turn poisonous when in the womb for too long … that was originally ‘relieved’ manually by doctors.” Doctors, it went on to say, performed this procedure so often that their fingers cramped, prompting the invention of a mechanical substitute.

This idea first appeared in Rachel Maines’ 1999 book The Technology of Orgasm. Since then it has cropped up in popular culture, documentaries, articles, and books. Although some writers disputed parts of her book, it wasn’t until a 2018 article by Hallie Lieberman and Eric Schatzberg that appeared in the peer-reviewed Journal of Positive Sexuality that Maines’ “hypothesis” (which she insists was no more than this) was thoroughly debunked. They looked at her sources and found them wanting, determining that doctors rarely performed this treatment on women.

Although Loudonville was never a hotbed of industry, in 1913 one of its most successful enterprises, Flxible, was founded by Loudonville native Hugo H. Young, a Harley-Davison dealer, and his partner Carl F. Dudte. Two years earlier Young had invented a much safer motorcycle sidecar with independent suspension that kept it on the ground when the motorcycle turned sharply or negotiated tight curves. Incorporated in 1914, the Flxible Side Car Company capitalized at $25,000. Its first rented factory space in Mansfield had a limited production capacity that stymied the company’s growth.

Enter Charles Kettering. His investment of $160,000 allowed the company to construct a much larger factory in Loudonville from which it was able to build sidecars for sale around the world. During World War I it made them fitted with machine guns, and when the GIs who rode in them came home, they bought their own. The popularity of the Flxible sidecar faded as more people purchased Model Ts. It also didn’t help that in 1925 a national ban on motorcycle sidecar racing was enacted, this having been prompted by a series of accidents.

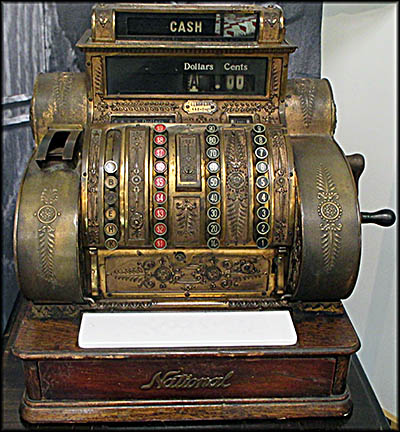

NCR Cash Register Designed by Charles Kettering

Charles Kettering

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Pioneer Kitchen

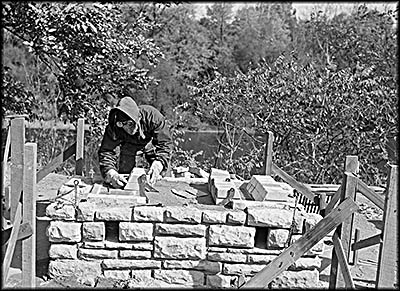

Here CCC workers are building a charcoal burner in Ohio's Ross County.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Workman Cabin

Reproducto Player-Piano-Organ

Young decided to find something else to manufacture, so he began building ambulances, buses, and even funeral cars. Buses, it turned out, were the most successful of these, and it was with this vehicle that the company went, although it continued to produce other things over the years including lockers. By the end of the 1920s, buses accounted for fifty percent of its sales and sidecars dropped to less than two percent. By 1940 it discontinued selling the latter and dropped “Side Car” from its name.

Flxible went through multiple owners over its existence, the last of which was the General Automotive Corporation. In December 1982 this company agreed to buy Flxible from its then-owner, the Grumman Corporation. General Automotive was founded in 1979 by Cruse Moss, who was its chairman when it purchased Flxible. Cruse, an industrial engineer who earned his degree at Ohio University, began his career as an executive at Kaiser Jeep’s automotive division before the company was acquired by the American Motors Corporation in 1970. For a time he worked for AMC’s military truck division, then he moved on to the White Motor Company as its president and CEO until it began bankruptcy proceedings.

A museum information sign claims Cruse had a history of bankrupting companies and may have embezzled money from Flxible, making this one of the reasons it went bankrupt and closed in 1996. I found no evidence, not even a hint, that Cruse did any such thing. Nor can he be blamed for the demise of the other companies for which he worked. Kaiser willingly sold to AMC, whose own collapse didn’t occur until long after Cruse left. The White Motor Company, too, was in trouble when he began his tenure there.

Flxible’s first major investor, Charles Kettering, was born in Loudonville on August 29, 1876. He graduated from Ohio State University in 1904 with a degree in engineering. His first job was at National Cash Register (NCR) where he was taught to invent things the public wanted to buy. His most significant contribution to NCR was his invention of an electric cash register that could also be operated by a hand crank, a working example of which is in the museum.

The mechanical variety had been invented by James Ritty, a Dayton saloon owner. Keen on keeping his thieving employees honest, he called it Ritty’s Incorruptible Cash Register. Though it worked, absolutely no one wanted to buy one. Like Ritty, John H. Patterson, general manager of the Southern Coal and Iron Company in Coalton, Ohio, had a problem with dishonest employees. He noticed that the although the company stores accounting books listed a profit of $12,000, in reality they had lost $6,000 because clerks repeatedly pilfered from the tills. So he ordered two of Ritty’s machines for $50 each. Seeing how well this solved his problem, in 1882 he and his brother, James, bought more. In 1884 they purchased the business from Ritty. And so was born NCR. Unsurprisingly, this “thief catcher” was not popular with café cashiers and bartenders.

Running into the same problem that Ritty had—no one wanted a cash register—Patterson assembled a team of aggressive salespeople and implemented an unprecedented advertising campaign to create demand. Salespeople received a commission for each one sold and had to meet quotas set by Patterson. He also created the NCR Primer, which told salespeople exactly what to say when pitching to a potential customer. It was the world’s first sales manual. Complementing this were training schools. All these measures worked. By 1910 NCR had captured about ninety percent of the market it had created.

Kettering left NCR in 1909. He, along with one of its executives, Edward Deeds, and a few of its moonlighting engineers, invented a battery powered automotive ignition system for Cadillac, a much safer alternative to the ofttimes dangerous hand crank. Kettering and Deeds called their new concern the Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company, which was shortened to Delco. In 1916 General Motors bought the company and integrated into its burgeoning conglomerate. Kettering worked for GM in several areas until his retirement. In his later years he founded or cofounded foundations and private laboratories to research cancer, solar power, photosynthesis, and to study magnetism.

He had one business venture outside of Delco. During World War I he and others partnered with Orville Wright to found the Dayton Wright Airplane Company, which developed an aerial torpedo, a small self-guided biplane with an explosive warhead. Top secret long after its development, it can be considered the forerunner of the cruise missile, though it never worked right. Delco, on the other hand, did have a solid contribution to the war effort. It designed and produced aircraft ignition systems and developed synthetic fuel.

Flxible went through multiple owners over its existence, the last of which was the General Automotive Corporation. In December 1982 this company agreed to buy Flxible from its then-owner, the Grumman Corporation. General Automotive was founded in 1979 by Cruse Moss, who was its chairman when it purchased Flxible. Cruse, an industrial engineer who earned his degree at Ohio University, began his career as an executive at Kaiser Jeep’s automotive division before the company was acquired by the American Motors Corporation in 1970. For a time he worked for AMC’s military truck division, then he moved on to the White Motor Company as its president and CEO until it began bankruptcy proceedings.

A museum information sign claims Cruse had a history of bankrupting companies and may have embezzled money from Flxible, making this one of the reasons it went bankrupt and closed in 1996. I found no evidence, not even a hint, that Cruse did any such thing. Nor can he be blamed for the demise of the other companies for which he worked. Kaiser willingly sold to AMC, whose own collapse didn’t occur until long after Cruse left. The White Motor Company, too, was in trouble when he began his tenure there.

Flxible’s first major investor, Charles Kettering, was born in Loudonville on August 29, 1876. He graduated from Ohio State University in 1904 with a degree in engineering. His first job was at National Cash Register (NCR) where he was taught to invent things the public wanted to buy. His most significant contribution to NCR was his invention of an electric cash register that could also be operated by a hand crank, a working example of which is in the museum.

The mechanical variety had been invented by James Ritty, a Dayton saloon owner. Keen on keeping his thieving employees honest, he called it Ritty’s Incorruptible Cash Register. Though it worked, absolutely no one wanted to buy one. Like Ritty, John H. Patterson, general manager of the Southern Coal and Iron Company in Coalton, Ohio, had a problem with dishonest employees. He noticed that the although the company stores accounting books listed a profit of $12,000, in reality they had lost $6,000 because clerks repeatedly pilfered from the tills. So he ordered two of Ritty’s machines for $50 each. Seeing how well this solved his problem, in 1882 he and his brother, James, bought more. In 1884 they purchased the business from Ritty. And so was born NCR. Unsurprisingly, this “thief catcher” was not popular with café cashiers and bartenders.

Running into the same problem that Ritty had—no one wanted a cash register—Patterson assembled a team of aggressive salespeople and implemented an unprecedented advertising campaign to create demand. Salespeople received a commission for each one sold and had to meet quotas set by Patterson. He also created the NCR Primer, which told salespeople exactly what to say when pitching to a potential customer. It was the world’s first sales manual. Complementing this were training schools. All these measures worked. By 1910 NCR had captured about ninety percent of the market it had created.

Kettering left NCR in 1909. He, along with one of its executives, Edward Deeds, and a few of its moonlighting engineers, invented a battery powered automotive ignition system for Cadillac, a much safer alternative to the ofttimes dangerous hand crank. Kettering and Deeds called their new concern the Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company, which was shortened to Delco. In 1916 General Motors bought the company and integrated into its burgeoning conglomerate. Kettering worked for GM in several areas until his retirement. In his later years he founded or cofounded foundations and private laboratories to research cancer, solar power, photosynthesis, and to study magnetism.

He had one business venture outside of Delco. During World War I he and others partnered with Orville Wright to found the Dayton Wright Airplane Company, which developed an aerial torpedo, a small self-guided biplane with an explosive warhead. Top secret long after its development, it can be considered the forerunner of the cruise missile, though it never worked right. Delco, on the other hand, did have a solid contribution to the war effort. It designed and produced aircraft ignition systems and developed synthetic fuel.

About half a block from the museum in Loudonville’s Central Park is a vintage cabin that looks like it came out of Little House on the Prairie. Built between 1838 and 1840 by Morgan Workman, it served as his home followed by several generations of his descendants. It has multiple rooms and an upstairs reachable only from a separate outside entrance. Because the building stood along the Mt. Vernon Pike & Stage Route, it was for a time transformed into an inn, and was once a meetinghouse for Church of the Brethren.

Abandoned in 1915, it was donated to the Mohican Historical Society (MHS) in 1963 by Mr. and Mrs. Gene Lifer on whose land it stood. MHS had the cabin moved to Central Park as part of Loudonville’s 1964 sesquicentennial with the idea of moving it elsewhere in the future. It proved so popular that it stayed. For a time the MHS ran it as a museum. After the construction of the Cleo Redd Fisher Museum in 1973, the cabin’s entry room was converted into a tourist information center and the rest of the cabin closed to the public until 1995. It has since been restored to be closer to what it once looked like and visitors can go though the whole thing.

Right next to Loudonville is Mohican State Park. In 1928 the Ohio Division of Forestry designated 850 acres of this area as Mohican State Forest. Much of the present park’s existing infrastructure can be traced back to the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), one of the many agencies created by the New Deal to put the unemployed back to work. Originally called the Emergency Conservation Work, only unmarried men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five could join, although this was later broadened to include out of work foresters, Native Americans, and veterans. Before their inclusion, unemployed foresters purposely set forest fires as acts of revenge for what they perceived as losing their jobs to cheap labor. When these foresters were allowed in, they became known as Local Experienced Men, or LEMs, used to spearhead the fighting of forest fires.

CCC men were trained by the U.S. Army and lived in camps run by it. The army was involved both because it had the ability to construct the camps, and it was hoped army discipline would keep all these young, unmarried men from becoming unruly. The CCC’s worksites were under civilian control. Critics worried the federal government was trying to militarize its youth, but the truth was Secretary of War George Dern and Colonel Duncan Major, who was on the CCC’s advisory board, tried to talk President Franklin D. Roosevelt out of using the army for this task for fear it would impact national defense. FDR didn’t take their advice.

One of those who joined the CCC and worked at Mohican was Alex James. Having lied about his age to get in—he was just sixteen at the time—he went to Fort Knox for basic training before being sent to Camp Mohican. When he arrived, the top of the gorge was bare, all its trees having been stripped by farmers for use as fields. One of the first goals was to restore the woodland that once thrived there, so James planted seedlings. He also built roads and dug ditches. During one especially harsh winter, he recalled, “I woke up to get my shoes one morning and they were frozen to the floor.” He suffered from frostbite while on road-clearing duty and spent a month in the infirmary recovering. Of the $30 he made a month, he sent all but $5 of it to his family. Although the townsfolk of Loudonville didn’t like the CCC men when they visited, they gladly took their money.

The CCC stayed in Mohican until 1940. It planted over 200,000 trees, built fire towers and roads, constructed bridges and picnic shelters, and carved out trails. In 1938 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built Pleasant Hill Dam, which created Pleasant Hill Lake. In 1947 another 270 acres were added to the park. In 1949 the Ohio State Department of Natural Resources named the area Clear Fork State Park after the waterway going through it. It was renamed Mohican State Park in 1966.

More about this area’s history can be found in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the chapter on Ashland County.🕜

Abandoned in 1915, it was donated to the Mohican Historical Society (MHS) in 1963 by Mr. and Mrs. Gene Lifer on whose land it stood. MHS had the cabin moved to Central Park as part of Loudonville’s 1964 sesquicentennial with the idea of moving it elsewhere in the future. It proved so popular that it stayed. For a time the MHS ran it as a museum. After the construction of the Cleo Redd Fisher Museum in 1973, the cabin’s entry room was converted into a tourist information center and the rest of the cabin closed to the public until 1995. It has since been restored to be closer to what it once looked like and visitors can go though the whole thing.

Right next to Loudonville is Mohican State Park. In 1928 the Ohio Division of Forestry designated 850 acres of this area as Mohican State Forest. Much of the present park’s existing infrastructure can be traced back to the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), one of the many agencies created by the New Deal to put the unemployed back to work. Originally called the Emergency Conservation Work, only unmarried men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five could join, although this was later broadened to include out of work foresters, Native Americans, and veterans. Before their inclusion, unemployed foresters purposely set forest fires as acts of revenge for what they perceived as losing their jobs to cheap labor. When these foresters were allowed in, they became known as Local Experienced Men, or LEMs, used to spearhead the fighting of forest fires.

CCC men were trained by the U.S. Army and lived in camps run by it. The army was involved both because it had the ability to construct the camps, and it was hoped army discipline would keep all these young, unmarried men from becoming unruly. The CCC’s worksites were under civilian control. Critics worried the federal government was trying to militarize its youth, but the truth was Secretary of War George Dern and Colonel Duncan Major, who was on the CCC’s advisory board, tried to talk President Franklin D. Roosevelt out of using the army for this task for fear it would impact national defense. FDR didn’t take their advice.

One of those who joined the CCC and worked at Mohican was Alex James. Having lied about his age to get in—he was just sixteen at the time—he went to Fort Knox for basic training before being sent to Camp Mohican. When he arrived, the top of the gorge was bare, all its trees having been stripped by farmers for use as fields. One of the first goals was to restore the woodland that once thrived there, so James planted seedlings. He also built roads and dug ditches. During one especially harsh winter, he recalled, “I woke up to get my shoes one morning and they were frozen to the floor.” He suffered from frostbite while on road-clearing duty and spent a month in the infirmary recovering. Of the $30 he made a month, he sent all but $5 of it to his family. Although the townsfolk of Loudonville didn’t like the CCC men when they visited, they gladly took their money.

The CCC stayed in Mohican until 1940. It planted over 200,000 trees, built fire towers and roads, constructed bridges and picnic shelters, and carved out trails. In 1938 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built Pleasant Hill Dam, which created Pleasant Hill Lake. In 1947 another 270 acres were added to the park. In 1949 the Ohio State Department of Natural Resources named the area Clear Fork State Park after the waterway going through it. It was renamed Mohican State Park in 1966.

More about this area’s history can be found in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the chapter on Ashland County.🕜