Clyde Museum

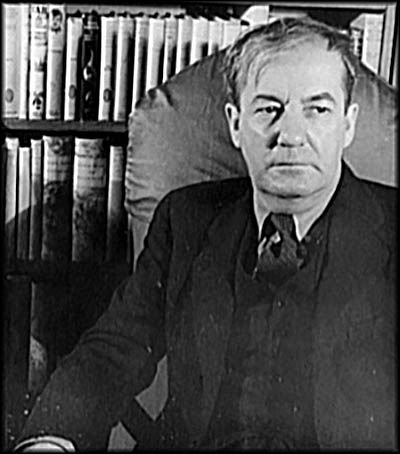

Sherwood Anderson

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Clyde Museum Annex

Clyde Museum (Original Part)

Just because a small town is virtually unknown outside the region in which it resides doesn’t meant it lacks a rich history filled with interesting events and people. Clyde, which the State of Ohio considers a city because it has more than 5,000 people, is just such a place. The first person of European descent to settle here was Jesse Benton, although he had no legal right to the land he took and was considered by the U.S. government a squatter. The parcel claimed by him belonged to Samuel Pogue, a veteran of the War of 1812 on which he, his stepson, Lyman Miller, and brothers-in-law, Amos Fenn and Dewey, settled, no doubt along with more extended family whose names were not on the information sign from which I gathered that tidbit of information. Andrew Jackson later issued a land grant in the area to Henry Burdick in 1834, though virtually nothing is known about him.

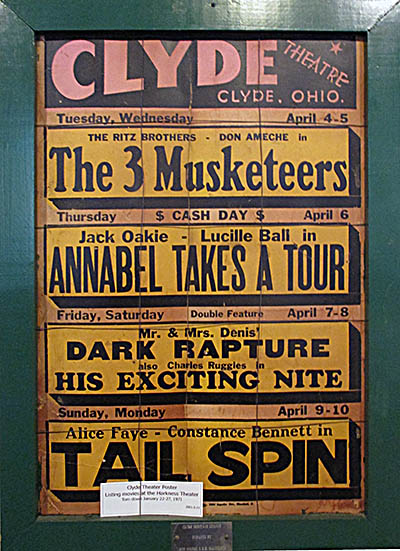

In the days before decent highways, Clyde had far more attractions on offer than it does today, including a theater. During Prohibition it became known as “Little Chicago” because it was a major waypoint for the transportation of illegal liquor. At one point this activity was centered in an area of town called Camp Grand, which was comprised of thirty cottages, a restaurant and gas station that were open all night long. Liquor made at a still in Wellington was transported weekly here in a purple hearse that parked behind the gas station to keep out of sight. Here other vehicles appeared, grabbed a portion of the wares on offer, then went to other destinations.

The hearse’s weekly visit didn’t go unnoticed by a local policeman named Hush. One night he pulled it over and asked to peek inside. As expected, he saw a casket. He commented to the hearse’s driver that he’d not seen one in that style for a while and wanted a closer look. He also asked if it carried a man or woman to which the driver answered that it was a man. Hush wanted to see him, but the driver balked. He might get in trouble with his boss. Hush insisted, so the driver opened it. Within was no corpse. Instead there were pints of bottled liquor wrapped up in paper. This was duly confiscated. With the hearse ruse exposed, other means of clandestine transportation would have to be used.

In the days before decent highways, Clyde had far more attractions on offer than it does today, including a theater. During Prohibition it became known as “Little Chicago” because it was a major waypoint for the transportation of illegal liquor. At one point this activity was centered in an area of town called Camp Grand, which was comprised of thirty cottages, a restaurant and gas station that were open all night long. Liquor made at a still in Wellington was transported weekly here in a purple hearse that parked behind the gas station to keep out of sight. Here other vehicles appeared, grabbed a portion of the wares on offer, then went to other destinations.

The hearse’s weekly visit didn’t go unnoticed by a local policeman named Hush. One night he pulled it over and asked to peek inside. As expected, he saw a casket. He commented to the hearse’s driver that he’d not seen one in that style for a while and wanted a closer look. He also asked if it carried a man or woman to which the driver answered that it was a man. Hush wanted to see him, but the driver balked. He might get in trouble with his boss. Hush insisted, so the driver opened it. Within was no corpse. Instead there were pints of bottled liquor wrapped up in paper. This was duly confiscated. With the hearse ruse exposed, other means of clandestine transportation would have to be used.

During the first years of the Great Depression and before Prohibition ended in December 1933, Alfred “Alf” A. Geiger ran a soft drink factory on Terry Drive that his children sold on the street during the summer. Each jug went for around $1, twenty-five cents of which the children kept for themselves. But this was just a front. Alf was busy making whiskey. Some stories say he distilled it on the top floor of his factory and moved it out via an underground tunnel, while others say he made it in the basement. His was just one of the places either making or selling illegal booze in Clyde and its surrounding area. The end of Prohibition killed the profitability of such activities, and soon after Clyde settled back into its more lawful self.

Like any community, Clyde takes pride in its nationally known sons and daughters, the most famous being the writer Sherwood Anderson, although one of his brother’s, Karl, was a successful all be it lesser known illustrator and muralist. A charcoal portrait of Ina Adare by Karl can be seen in the museum. Karl was taught art by John Tichenor, a native of Clyde whose portrait of Maud Ramsay is also in the museum. In fact, the museum has a ton of art on display, some of it really good—especially works by local high school art teacher George White—and some of it is so awful it has to be seen to be believed.

The museum has quite a few photos of Sherwood Anderson as well as a copy of his book Winesburg, Ohio in a display case. Clyde loves this book because Winesburg was a stand in for the city, although its characters were based on people Anderson knew in Chicago, where he lived much of his life. Winesburg, Ohio was no commercial success, probably because it’s filled with plotless stories, an Anderson specialty. It is for this reason people in the world of literature love this guy and the average American reader doesn’t.

Like any community, Clyde takes pride in its nationally known sons and daughters, the most famous being the writer Sherwood Anderson, although one of his brother’s, Karl, was a successful all be it lesser known illustrator and muralist. A charcoal portrait of Ina Adare by Karl can be seen in the museum. Karl was taught art by John Tichenor, a native of Clyde whose portrait of Maud Ramsay is also in the museum. In fact, the museum has a ton of art on display, some of it really good—especially works by local high school art teacher George White—and some of it is so awful it has to be seen to be believed.

The museum has quite a few photos of Sherwood Anderson as well as a copy of his book Winesburg, Ohio in a display case. Clyde loves this book because Winesburg was a stand in for the city, although its characters were based on people Anderson knew in Chicago, where he lived much of his life. Winesburg, Ohio was no commercial success, probably because it’s filled with plotless stories, an Anderson specialty. It is for this reason people in the world of literature love this guy and the average American reader doesn’t.

I found it odd that the museum had virtually no biographical details about him on any of its information signs, so I read up on him in American National Biography. Anderson was born on September 13, 1876, in Camden, Ohio, a village near Dayton. He was raised in Clyde along with six siblings. Coming from an impoverished family, he made it through just one year of high school because he spent most of his time trying to earn money, giving him the nickname “Jobby.” He enlisted to fight in the Spanish-America war but it ended before he saw combat. After some schooling at Springfield, Ohio’s Wittenberg Academy, he made his way to Chicago where he got into advertising as a copyrighter and salesman for ad space. Here he married Cornelia Platt Lane with whom he had three children. After a stint in the mail-order business, he started the Anderson Manufacturing Company in Elyria, Ohio. So far his life seems pretty ordinary.

Then in 1912 it took a U-turn that probably explains why the museum was less keen to give too much away about his personal life. He had a four day mental involving the questioning of his purpose in life that ended with him in a Cleveland hospital. A year later he abandoned his family and returned to Chicago to become a writer. The next year he published his first short story, and a year after that, his first novel, Windy McPherson’s Son.

In his post-Winesburg, Ohio works, he became exceedingly interested in sexual themes and sex in general, possibly explaining why he married four times. He eventually abandoned writing fiction, and at one point bought both Republican and Democratic newspapers to which he contributed essays. His death was not typical. While on a trip to South America he was killed by a toothpick. Really. He swallowed one whole and it caused peritonitis, an infection of the abdominal wall.

Then in 1912 it took a U-turn that probably explains why the museum was less keen to give too much away about his personal life. He had a four day mental involving the questioning of his purpose in life that ended with him in a Cleveland hospital. A year later he abandoned his family and returned to Chicago to become a writer. The next year he published his first short story, and a year after that, his first novel, Windy McPherson’s Son.

In his post-Winesburg, Ohio works, he became exceedingly interested in sexual themes and sex in general, possibly explaining why he married four times. He eventually abandoned writing fiction, and at one point bought both Republican and Democratic newspapers to which he contributed essays. His death was not typical. While on a trip to South America he was killed by a toothpick. Really. He swallowed one whole and it caused peritonitis, an infection of the abdominal wall.

The Clyde Museum is run by the Clyde Heritage League (CHL), which was founded in 1975 to preserve historical objects and buildings, and to promote Clyde’s history. Its primary mover was Thaddeus B. Hurd, a notoriously frugal man whose fortune still benefits the museum annually. The museum’s website is a bit misleading. It makes you think that your visit will result in tours of the main museum, the McPherson House (in which General James B. McPherson was raised—more on him later), and Heritage Hall. The McPherson House is only open by appointment, and Heritage Hall, although controlled by the museum, is rented out for other uses.

The museum’s core collection traces its history back to the Clyde Library Museum that was founded in 1931–32 by Dick Wolfe, a coach and science teacher. This venture was located in the Clyde Public Library’s basement and could be visited on Sundays. The collection was transferred to the CHS in 1981, and most of it can be seen in a beautiful former Episcopal Church that opened in 1885 and served its congregation until 1960 after which it became an antique and gem shop. When CHS acquired the building, it converted it into the museum, which opened in 1987. Since then an additional annex and a garage to house historical vehicles have been added.

In the garage is a 1904 runabout car built by the Elmore Manufacturing Company, a Clyde automaker that had originally made bicycles in nearby Elmore. Its Clyde facility had previously been an organ-making factory. The roundabout in the museum didn’t have a lot of pep—two cylinder engines don’t tend to—and its engine had no valves. Elmore Manufacturing was eventually sold to General Motors and briefly served as one of its divisions. After the company moved manufacturing from Clyde to Detroit, the Krebs Car Company took over its Clyde facility in 1912 and there built trucks until around 1916.

There are two firetrucks in the museum’s garage. One is a severely modified 1926 Ford Model T, and the other a 1920 Clydesdale truck. The Clydesdale Motor Truck Company (originally called the Clyde Cars Company) built military vehicles during World War I. In 1917 it started making civilian trucks in in the old Elmore Manufacturing (or really Klebs) facility and continued to do so until shutting its doors in 1939. The company only made truck bodies. Engines were provided by Hesselman Diesel, which were notoriously unreliable and hard to tune up. During its brief existence, it built just a single firetruck, the one found here. It still runs and sometimes shows up in parades. The garage is filled with other artifacts that you can’t drive, including a vintage washing machine, one of the museum’s aforementioned bad paintings, a telephone exchange control board, and a Trescott Grader Apple Sorter once used by a local fruit farm.

The museum’s core collection traces its history back to the Clyde Library Museum that was founded in 1931–32 by Dick Wolfe, a coach and science teacher. This venture was located in the Clyde Public Library’s basement and could be visited on Sundays. The collection was transferred to the CHS in 1981, and most of it can be seen in a beautiful former Episcopal Church that opened in 1885 and served its congregation until 1960 after which it became an antique and gem shop. When CHS acquired the building, it converted it into the museum, which opened in 1987. Since then an additional annex and a garage to house historical vehicles have been added.

In the garage is a 1904 runabout car built by the Elmore Manufacturing Company, a Clyde automaker that had originally made bicycles in nearby Elmore. Its Clyde facility had previously been an organ-making factory. The roundabout in the museum didn’t have a lot of pep—two cylinder engines don’t tend to—and its engine had no valves. Elmore Manufacturing was eventually sold to General Motors and briefly served as one of its divisions. After the company moved manufacturing from Clyde to Detroit, the Krebs Car Company took over its Clyde facility in 1912 and there built trucks until around 1916.

There are two firetrucks in the museum’s garage. One is a severely modified 1926 Ford Model T, and the other a 1920 Clydesdale truck. The Clydesdale Motor Truck Company (originally called the Clyde Cars Company) built military vehicles during World War I. In 1917 it started making civilian trucks in in the old Elmore Manufacturing (or really Klebs) facility and continued to do so until shutting its doors in 1939. The company only made truck bodies. Engines were provided by Hesselman Diesel, which were notoriously unreliable and hard to tune up. During its brief existence, it built just a single firetruck, the one found here. It still runs and sometimes shows up in parades. The garage is filled with other artifacts that you can’t drive, including a vintage washing machine, one of the museum’s aforementioned bad paintings, a telephone exchange control board, and a Trescott Grader Apple Sorter once used by a local fruit farm.

Most of the museum’s artifacts are located in the aforementioned former Episcopal church that is divided into themed sections. One area, for example, contains photos and items from Clyde’s businesses, another is dedicated to Native American history, and still another to Clyde High School. At one end of the room is a desk used by the newspaper Clyde Enterprise, and at the other end artifacts from that paper’s printing press. The Clyde Enterprise, which only reported local news, was founded in 1878 by J.C. Loveland and Henry F. Paden. After a 138 year run, it published its last edition on June 1, 2016.

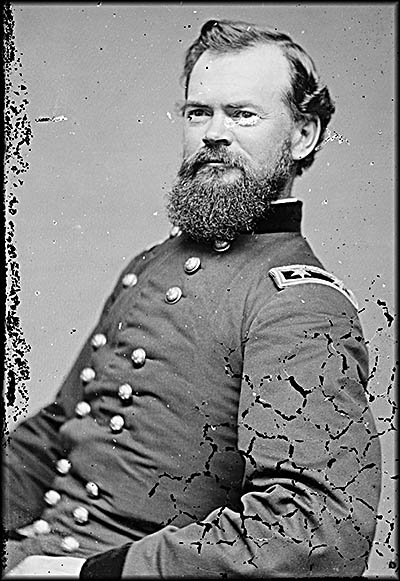

In one of the museum’s side rooms you will find Civil War memorabilia and information about those in Clyde who served in that conflict. This includes the sword, revolver, and other personal effects of Major General James Birdseye McPherson, the highest ranking Union general killed in combat. Now if you ask the average person on the street to name Civil War generals off the top of their head, McPherson’s name isn’t likely to come up, but Civil War buffs know just how important he was to the North’s win over the South. Not only did General Ulysses S. Grant value him greatly, he considered him his best friend.

McPherson was born in Clyde on November 14, 1828. In 1849 he received an appointment at West Point and in 1853 graduated at the top of his class. His West Point roommate was none other than John Bell Hood, later a Confederate general. Unlike many of the high ranking officers who would one day fight in the Civil War, McPherson had missed serving in the Mexican-American War by several years, so his military career began during peacetime. He was an accomplished engineer and became part of the Corps of Engineers, eventually being chosen to oversee the fortification of Alcatraz Island.

When the Civil War broke out, he was sent to Boston to fortify the harbor. Desiring a field command, he asked his former commander, General Henry W. Halleck, for one. Halleck, who had just been put in charge of the Department of Missouri, brought McPherson in as an aid and assistant engineer. In February 1862, McPherson became Grant’s chief engineer just in time for his siege of Fort Donelson, the fight at Shiloh, and the attack on Corinth, Mississippi.

McPherson was promoted to brigadier general in August 1862 to serve as Grant’s superintendent of railroads. He first commanded troops of his own during the Battle of Corinth, and was promoted to a major general of volunteers. As Grant’s and Sherman’s fortunes rose, so did McPherson’s. He took charge of the Army of the Tennessee in 1864, forcing him to scrap a planned furlough to marry his sweetheart, Emily Hoffman, so he could follow Sherman to Atlanta. And it was in this city while fighting General Hood’s force that McPherson was shot and killed by a Confederate skirmisher on July 22, 1864. He was just thirty-five.🕜

McPherson was born in Clyde on November 14, 1828. In 1849 he received an appointment at West Point and in 1853 graduated at the top of his class. His West Point roommate was none other than John Bell Hood, later a Confederate general. Unlike many of the high ranking officers who would one day fight in the Civil War, McPherson had missed serving in the Mexican-American War by several years, so his military career began during peacetime. He was an accomplished engineer and became part of the Corps of Engineers, eventually being chosen to oversee the fortification of Alcatraz Island.

When the Civil War broke out, he was sent to Boston to fortify the harbor. Desiring a field command, he asked his former commander, General Henry W. Halleck, for one. Halleck, who had just been put in charge of the Department of Missouri, brought McPherson in as an aid and assistant engineer. In February 1862, McPherson became Grant’s chief engineer just in time for his siege of Fort Donelson, the fight at Shiloh, and the attack on Corinth, Mississippi.

McPherson was promoted to brigadier general in August 1862 to serve as Grant’s superintendent of railroads. He first commanded troops of his own during the Battle of Corinth, and was promoted to a major general of volunteers. As Grant’s and Sherman’s fortunes rose, so did McPherson’s. He took charge of the Army of the Tennessee in 1864, forcing him to scrap a planned furlough to marry his sweetheart, Emily Hoffman, so he could follow Sherman to Atlanta. And it was in this city while fighting General Hood’s force that McPherson was shot and killed by a Confederate skirmisher on July 22, 1864. He was just thirty-five.🕜

Clyde Museum Garage

1904 Elmore Runabout (Made in Clyde)

1926 Ford Motor Firetruck

Trescott Grader Apple Sorter

Major John B. McPherson’s Battle Sword

McPherson’s 1851 Navy Colt 36 Caliber Revolver

Major General James B. McPherson

Library of Congress

Library of Congress