Crestline Historical Society and Museum

Exterior

Interior

Model and Toy Trains

Antique clock enthusiasts will find much to see here.

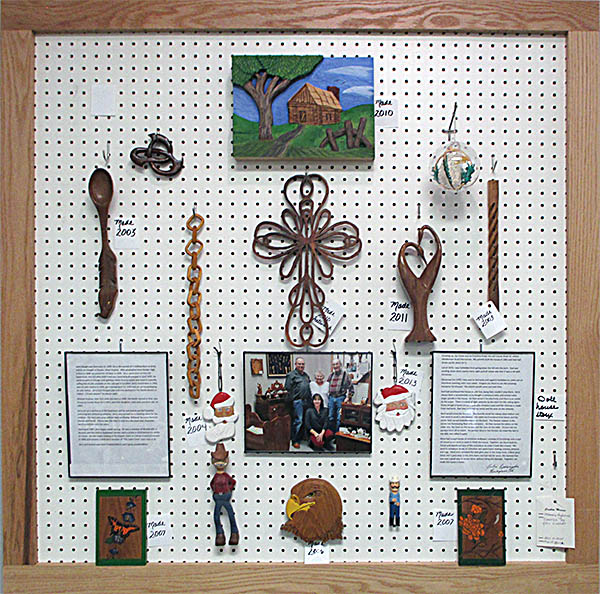

Jerry Haught Sampler

The model of Rensseaer Livingstone's house was made by the Crestline Home Workshop Club in 1967.

Stained Glass Window from Trory's Drug Store

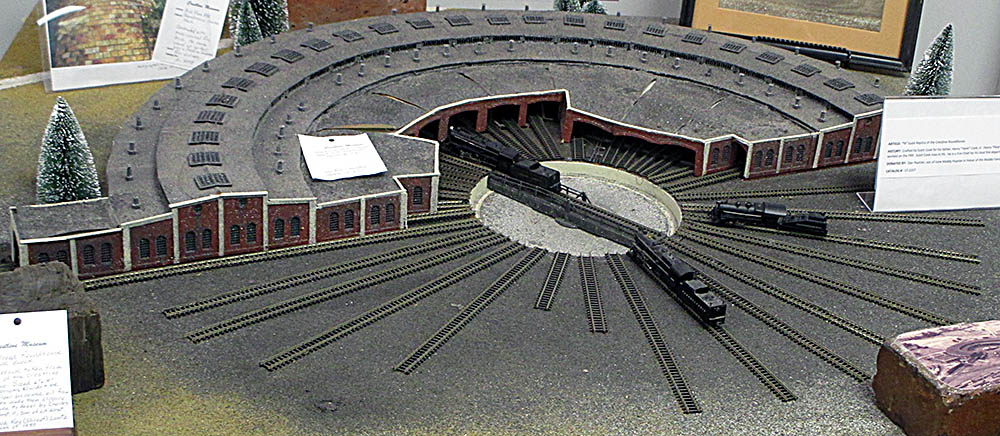

This model of the Pennsylvania Railroad's Crestline roundhouse was made by Scott Cook.

This sewing machine, made around 1890, was used by three generations of the Sabo family.

I don’t recall ever visiting Galion, Ohio, though I’ve little doubt I passed through at some point in my life. It’s not somewhere I intended to go, either, until a memorial service brought me there. This town is about an hour from my house, so I decided that since I was in the area and it was a Saturday, I’d see if there were any historic sites or museums to visit. It happened that the Crestline Historical Society and Museum in Crawford County had its doors open that day, which was lucky for me because it’s only open for two hours in the mid-afternoon on the first (full) and third weekends of the month or by appointment. It’s usually closed all of December and January. Its is in a standard Midwest-style brick building that has no fancy architecture to set it apart from other utilitarian buildings of its type. Inside is something else entirely.

Many of the museum’s exhibits are in displayed in antique cases, some of which came from the defunct Crestline drugstore Trory’s. One artifact from that store, a stained glass window, had at one time resided at Cedar Point Amusement Park before returning to its hometown. The village of Crestline was (and to a degree still is) a railroad town, and this explains why a set of train track decals decorate the floor. The museum staff regularly change exhibits (excepting the ones about the railroad) because they have far more in storage than they can display, and it gives repeat visitors something new to look at.

Many of the museum’s exhibits are in displayed in antique cases, some of which came from the defunct Crestline drugstore Trory’s. One artifact from that store, a stained glass window, had at one time resided at Cedar Point Amusement Park before returning to its hometown. The village of Crestline was (and to a degree still is) a railroad town, and this explains why a set of train track decals decorate the floor. The museum staff regularly change exhibits (excepting the ones about the railroad) because they have far more in storage than they can display, and it gives repeat visitors something new to look at.

One of the museum’s exhibits showcases the work of folk artist Jerry Haught, who was born in West Virginia on July 12, 1930. After graduating from high school, he went into the Navy, serving from 1948 to 1953. After mustering out, he moved to Chicago. Told that there were jobs at the railroad in Crestline, he moved to the area and worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) for a time before moving on to North Electric in Galion. In his leisure time, he and his wife, Joanne, restored antique furniture in their basement. Jerry soon started making things out of wood, items that included a china cabinet, doll house, and toy barn. In 1987 he got into wood carving, and many of these items can be seen in the display shown in the photo below.

The aforementioned Trory’s Drug Store stayed in business for fifty years and was started by Charles E. Trory. He married Grace Wertz on July 9, 1911, whose father, Doctor Jacob Wertz, had served as a battlefield surgeon during the Civil War in the Grand Army of the Republic. Although he forbade alcohol, tobacco and cider from entering his house, he had no prohibition against educating his daughter. After high school she attended and graduated from the Ashland College of Music in 1903. According to an information sign, “She was employed as Supervisor of Music for Jackson County Schools for many years.” Jackson county is no where near Crestline, so possibly she did this before getting married. Her taste in music ranged from opera to classical to ragtime to Gershwin. One wonders what her father though of ragtime, which people of his generation rarely liked.

Crestline was officially founded in 1851. Its origin can in part be traced to a wealthy fellow from New York State, Rensselaer Livingston, who brought his family to Crawford County in 1850. Descended from British aristocracy, he grew up at Livingston Manor in the Hudson River, which was built on land given to his great-grandfather, Lord Robert Livingston, by King Charles II in 1686.

Rensselaer had an impressive house built on Crawford County land purchased from William and Sarah Dille for $2,050. In 1851 he bought eighty-three more acres from Francis Cornwell, ten from Christopher Baker, and twelve from Philip Eichhorn, then had it platted (that is, surveyed and divided into lots) by Joseph Meyer, the Crawford County Surveyor. President Zachary Taylor made Livingston the postmaster of his new town, a post Livingston didn’t get to enjoy for long. He died in 1853 and had the distinction of being the first person buried in the new cemetery.

Crestline was officially founded in 1851. Its origin can in part be traced to a wealthy fellow from New York State, Rensselaer Livingston, who brought his family to Crawford County in 1850. Descended from British aristocracy, he grew up at Livingston Manor in the Hudson River, which was built on land given to his great-grandfather, Lord Robert Livingston, by King Charles II in 1686.

Rensselaer had an impressive house built on Crawford County land purchased from William and Sarah Dille for $2,050. In 1851 he bought eighty-three more acres from Francis Cornwell, ten from Christopher Baker, and twelve from Philip Eichhorn, then had it platted (that is, surveyed and divided into lots) by Joseph Meyer, the Crawford County Surveyor. President Zachary Taylor made Livingston the postmaster of his new town, a post Livingston didn’t get to enjoy for long. He died in 1853 and had the distinction of being the first person buried in the new cemetery.

This is a melodian, an organ-like instrument made about 100 years ago and owned by the Menges family.

Around this time, the Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati Railroad made plans to create a new line connecting Galion and Bucyrus. For it they’d need a station roughly in its middle, but neither Galion, Bucyrus, Mansfield, nor Leesville wanted it. Undaunted, CC&C officials decided to build a town of their own. Livingston, which wanted a railroad to go through it, was about half a mile to the north of the CC&C’s tracks, so it merged with the CC&C’s new town being planned by the CC&C. It was renamed Crestline because the local inhabitants mistakenly believed that they lived along the dividing line where Ohio Rivers either went north to Lake Erie or south into the Ohio River.

The CC&C was eventually absorbed by the New York Central Railroad. When the Ohio & Pennsylvania Railroad, which later became part of the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), came through the village, it made Crestline an important link between the two lines. The PRR also built freight yards and shops in the village, and during World War I, the government funding the construction of a roundhouse at a cost of about $2 million. It had thirty-six stalls and remained in use until 1968.

Crestline and the railroad yards have the unwanted distinction of being blown up. On November 1, 1903, a freight car (or possibly two) carrying dynamite exploded, an event probably caused by a jolt during the coupling or uncoupling of railcars. The explosion wrecked 250 train cars, damaged every house in Crestline, and was felt as far away as Canton, which is eighty-seven miles away. According to the November 3, 1903, issue of the Stark County Democrat, the explosion created “a hole fully 60 feet long, 30 feet wide and 10 to 15 feet deep.… A huge piece of iron, said to weigh 200 pounds, was thrown into the air and crashed through a farm house about a hundred feet distance.… The windows and lamps in all the houses and stores for miles around were shattered.” The Cleveland Plain Dealer reported that the hole was 100 feet in diameter and thirty-five deep.

Amazingly, no one was killed and only five were injured. Having occurred on a Sunday morning, many worshipers at church found explosion particularly scary—was this the end of the world? The damage caused was estimated to be between $400,000 and $500,000 ($13.7 to $17.2 million today). The accident prompted the American Railway Association to regulate the transportation of hazardous chemicals. In 1908, Congress gave the Interstate Commerce Commission, which oversaw railroads, the ability to regulate the shipping of explosives.

During World War II, Crestline contributed to the war effort at a very local level. At that time railroads moved millions of troops across the United States. Trains had a stop more frequently than today, and at many of the depots, groups of volunteers ran canteens to feed passing troops. The one at Crestline was founded by Marie Moran, whose workers came mainly from church groups. All the food and coffee were donated. The Crestline canteen started on August 24, 1942. Trains passing through the village stopped for a minimum of ten minutes to allow for the changing of crews and locomotives. To get to the troop trains, volunteers had to cross two of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s main tracks. One day a couple of younger volunteers not paying attention were nearly run over by a train, an incident that prompted the PRR to ban the canteen from its yard.

The CC&C was eventually absorbed by the New York Central Railroad. When the Ohio & Pennsylvania Railroad, which later became part of the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), came through the village, it made Crestline an important link between the two lines. The PRR also built freight yards and shops in the village, and during World War I, the government funding the construction of a roundhouse at a cost of about $2 million. It had thirty-six stalls and remained in use until 1968.

Crestline and the railroad yards have the unwanted distinction of being blown up. On November 1, 1903, a freight car (or possibly two) carrying dynamite exploded, an event probably caused by a jolt during the coupling or uncoupling of railcars. The explosion wrecked 250 train cars, damaged every house in Crestline, and was felt as far away as Canton, which is eighty-seven miles away. According to the November 3, 1903, issue of the Stark County Democrat, the explosion created “a hole fully 60 feet long, 30 feet wide and 10 to 15 feet deep.… A huge piece of iron, said to weigh 200 pounds, was thrown into the air and crashed through a farm house about a hundred feet distance.… The windows and lamps in all the houses and stores for miles around were shattered.” The Cleveland Plain Dealer reported that the hole was 100 feet in diameter and thirty-five deep.

Amazingly, no one was killed and only five were injured. Having occurred on a Sunday morning, many worshipers at church found explosion particularly scary—was this the end of the world? The damage caused was estimated to be between $400,000 and $500,000 ($13.7 to $17.2 million today). The accident prompted the American Railway Association to regulate the transportation of hazardous chemicals. In 1908, Congress gave the Interstate Commerce Commission, which oversaw railroads, the ability to regulate the shipping of explosives.

During World War II, Crestline contributed to the war effort at a very local level. At that time railroads moved millions of troops across the United States. Trains had a stop more frequently than today, and at many of the depots, groups of volunteers ran canteens to feed passing troops. The one at Crestline was founded by Marie Moran, whose workers came mainly from church groups. All the food and coffee were donated. The Crestline canteen started on August 24, 1942. Trains passing through the village stopped for a minimum of ten minutes to allow for the changing of crews and locomotives. To get to the troop trains, volunteers had to cross two of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s main tracks. One day a couple of younger volunteers not paying attention were nearly run over by a train, an incident that prompted the PRR to ban the canteen from its yard.

Undaunted, Moran set up a new canteen on private property along the tracks on Washington Street. The ladies running the canteen anticipated feeding about 200 men a day, a wildly lowball figure. The station daily received between 2,000 to 2,500 troops daily with peaks of 5,000. The Crestline canteen also offered servicemen a free taxi service. The PRR realized it’d made a mistake denying the volunteers access to it grounds, so in April 1943 it built a larger white hut on South Crestline Street that was funded with pennies donated by the town’s children.

The canteen meant a great deal to the young men being transported to war. Eighteen years after passing through in 1943, Gerald Green wrote to two volunteers of the canteen a letter of appreciation. He recalled being fed chocolate cake and claimed it was the best he’d ever had. Arriving in Crestline on a miserable March day (is there any other kind in Ohio?), he was being transported from Camp Upton, New York, to California. Like many of his fellow draftees, he felt lonely and down. Then came a pair of children—a boy of about ten and a girl of about thirteen who were likely brother and sister—carrying baskets filled with goodies: sandwiches, cakes, and fruit among them. This small act of kindness immediately improved the morale of all the servicemen on board the train.🕜

The canteen meant a great deal to the young men being transported to war. Eighteen years after passing through in 1943, Gerald Green wrote to two volunteers of the canteen a letter of appreciation. He recalled being fed chocolate cake and claimed it was the best he’d ever had. Arriving in Crestline on a miserable March day (is there any other kind in Ohio?), he was being transported from Camp Upton, New York, to California. Like many of his fellow draftees, he felt lonely and down. Then came a pair of children—a boy of about ten and a girl of about thirteen who were likely brother and sister—carrying baskets filled with goodies: sandwiches, cakes, and fruit among them. This small act of kindness immediately improved the morale of all the servicemen on board the train.🕜

The museum is certainly full of surprises. It has, for example, a walking stick that belonged to John Chapman, better known as Johnny Appleseed. The information sign says, “his purpose was to provide apple trees for the pioneers to have nourishment.” This is not entirely true. Born in Massachusetts on September 26, 1774, Chapman got his seeds from a nursery he started along the Allegheny River. But his work selling apple seeds to pioneers, who could use them to plant that apple orchards that qualified as one of the improvements needed to keep their government-discounted land, was just a means to an end. Chapman’s land acquisitions and sales of apple seeds (which he gave to those who couldn’t afford them) were merely a way for him to fund his missionary work. He preached the dogma of Emanuel Swedenborg, a Swedish theologian now forgotten by all those except for experts on obscure Swedish theologians.