Dennison Railroad Depot Museum

Dennison Railroad Depot Museum

Dennison Railroad Musuem

This is a sign from one of the stops along the Panhandle route.

Inside the Museum

Every railroad museum I’ve been to has its own distinct character and, for want of a better term, theme, and the Dennison Railroad Depot Museum is no exception. Its focus is on the intwining history of the town of Dennison and the railroad that both fueled its growth and caused its worst hardships. Along the way the museum diverts into related topics, all of them interesting and relevant. When I write these travel logs I always pick highlights of what I found because I want readers to visit a given place and see far more than what I’ve covered. With this museum if I tried to write about every topic it highlights, I would wind up with a full length book! It is any case the best railroad museum I’ve been to, high praise indeed because the others I’ve seen were all excellent in and of themselves.

The history of Dennison begins not in the town itself but rather with the city of Uhrichsville next door. The first settler of European decent to arrive in the spot that would become Uhrichsville was Michael Uhrich. Here he built a mill on the Stillwater Creek in 1804 (or 1806—sources differ). He laid out the town he called Waterford in 1833, but about six years later it was renamed to Uhrichsville. Nearly thirty-eight miles to the east as the crow flies, the residents of Steubenville thought it might be a good idea to lay down an east-west railroad with their town as its eastern terminus. After some lobbying, the Ohio Legislature issued a charter for the Steubenville & Indiana Railroad on February 24, 1848. The company was officially organized in 1850 and during this time the people of Uhrichsville convinced it to run through their town. The first passenger train came through on September 10, 1854.

The history of Dennison begins not in the town itself but rather with the city of Uhrichsville next door. The first settler of European decent to arrive in the spot that would become Uhrichsville was Michael Uhrich. Here he built a mill on the Stillwater Creek in 1804 (or 1806—sources differ). He laid out the town he called Waterford in 1833, but about six years later it was renamed to Uhrichsville. Nearly thirty-eight miles to the east as the crow flies, the residents of Steubenville thought it might be a good idea to lay down an east-west railroad with their town as its eastern terminus. After some lobbying, the Ohio Legislature issued a charter for the Steubenville & Indiana Railroad on February 24, 1848. The company was officially organized in 1850 and during this time the people of Uhrichsville convinced it to run through their town. The first passenger train came through on September 10, 1854.

Dennison was sometimes referred to as the “Altoona of the Panhandle,” the meaning of which none of the museum’s information signs explained. Altoona is a railroad town in Pennsylvania that grew exponentially because the Pennsylvania Railroad put a major yard here. Panhandle is a reference to a part of West Virginia that is shaped like a pan’s handle which juts up between Ohio and Pennsylvania through which the PC & CR’s tracks passed.

In 1873 a permanent depot was built in Dennison, the very one that now serves as a museum. (It also has a restaurant that I didn’t visit.). The depot’s original windows were painted black during World War II in case enemy bombers attacked by (which was a technical impossibility at the time, but a sound precaution since who knew what the Germans had in their air force?). The windows were then boarded over. When the building was restored, the boards were removed and the windows cleaned.

In 1890 the Pennsylvania Railroad bought the PC & CR along its Dennison yards (although the PC & CR’s name didn’t change to Pennsylvania Railroad until 1921). The Pennsylvania Railroad soon upgraded the yard’s shops. Railroads were exceedingly dangerous to work for or even ride on in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in large part because many roads didn’t value the lives of their workers and cut corners rather than invest in safety. The Pennsylvania Railroad was different. Its trains had the new Westinghouse airbrakes that were far more effective and much safer to implement than the old car by car type. Pennsylvania Railroad cars, if unexpectedly uncoupled while moving, would automatically come to a halt. The tracks themselves were made of steel rather than the less than durable iron. Improved safety switches were put in.

In 1873 a permanent depot was built in Dennison, the very one that now serves as a museum. (It also has a restaurant that I didn’t visit.). The depot’s original windows were painted black during World War II in case enemy bombers attacked by (which was a technical impossibility at the time, but a sound precaution since who knew what the Germans had in their air force?). The windows were then boarded over. When the building was restored, the boards were removed and the windows cleaned.

In 1890 the Pennsylvania Railroad bought the PC & CR along its Dennison yards (although the PC & CR’s name didn’t change to Pennsylvania Railroad until 1921). The Pennsylvania Railroad soon upgraded the yard’s shops. Railroads were exceedingly dangerous to work for or even ride on in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in large part because many roads didn’t value the lives of their workers and cut corners rather than invest in safety. The Pennsylvania Railroad was different. Its trains had the new Westinghouse airbrakes that were far more effective and much safer to implement than the old car by car type. Pennsylvania Railroad cars, if unexpectedly uncoupled while moving, would automatically come to a halt. The tracks themselves were made of steel rather than the less than durable iron. Improved safety switches were put in.

The new road had one major flaw. It didn’t connect to any other lines, so it had no way to easily transfer goods coming from the east or heading west to its own trains. The Panic of 1857 caused its finances to tank and by 1868 it was part of a new road made up of other bankrupted lines called the Panhandle Railway, which was soon merged with a couple more railroads to become the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati & St. Louis Railway (PC & SL). In 1864, an earlier iteration of that—the Pittsburgh, Columbus & Cincinnati Railroad—decided to build a massive yard in an area just east of Uhrichsville. The next year a village to accommodate the workers, Dennison, was founded. This place was chosen for the new yard because it was the midpoint between Columbus and Pittsburgh.

One soldier who stopped in Dreamsville, whose quote I found on a museum information sign, recalled, “I was feeling just about as blue as a boy can be, all of the sudden the train pulled into the town of Dennison, Ohio, of which I had never heard but which I will never forget now. The food warmed my body, and the thoughtfulness warmed my heart. I got back on the train an entirely different person.” On the fiftieth anniversary celebration of Dreamsville, a solider who had passed through came to Dennison and donated a sandwich bag he’d been given there! One wonders how he managed to preserve it considering he was heading off to war, which might make an interesting story in and of itself.

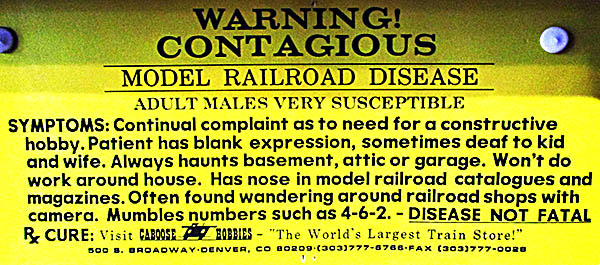

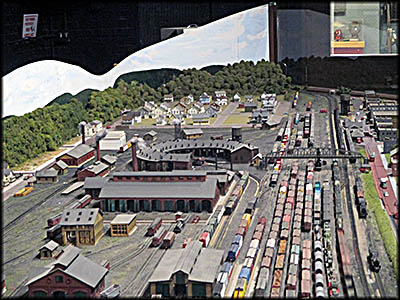

In one room of the museum is an exceedingly large and exceptionally well made model railroad of the Dennison train yards and shops. This was created by the Dennison Area Model Railroaders. Hit a button and watch it go. Accompanying this is the following sign:

In one room of the museum is an exceedingly large and exceptionally well made model railroad of the Dennison train yards and shops. This was created by the Dennison Area Model Railroaders. Hit a button and watch it go. Accompanying this is the following sign:

The museum extends beyond the Depot into a series of former passenger cars. When I saw these from outside I didn’t think much of it because once you’ve seen the inside of one passenger car from the 1940s, you’ve pretty much seen them all. But not so here. The cars’ original interiors had been gutted and replaced with a series of excellent exhibits. Some of the cars are designed to look like a specific type of railcar, such as Pullman sleepers, a galley, a pantry, a kitchen, and a dining car.

Keeping with the Depot’s earlier World War II theme, a military hospital car was filled with bunks, a small operating theater, a nurse’s station, and other accruements one would expect to see in one of these. These cars were part of a military hospital train, which usually had sixteen coaches that included cars for infectious patients, doctors’ quarters, nurses’ quarters, a pharmacy, a kitchen and a mess. Most military trains carried around 375 beds but had no air conditioning, so pleasant they were not, especially in the hot months of the year. Nor did the jostling and bumping train as its traveled make the lives of those painful wounds any more comfortable. Oh, and then there were the flies and stench of gangrene and other noxious diseases the wounded often suffer from. Nurses worked twelve hour shifts (or longer) and among other duties tried to make patients as comfortable as possible.

One car was converted into an exhibit about Swing music, the most popular type in American throughout World War II. Although some music critics don’t consider Swing a subgenre of Jazz, a number of Jazzmen were in Swing bands and their influence is unmistakable. Two Swing bandleaders who the exhibit highlights are Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey. Even those who know nothing about Swing will have at some point have heard Goodman’s “Sing Sing Sing” because it’s been in so many movies. Tommy Dorsey’s song “Opus One” might not be as familiar, but it’s a perfect example of Swing music. I was surprised that examples of this music wasn’t playing in the background or available to hear in some way, but possibly there are rights issues and that is why none was to be found. You can go to a live mike in this car and sing your heart out. Swing fell out favor after World War II in part because the cost of running a big band (which usually had seventeen members) had gotten too expensive, and American public’s taste had shifted to preferring songs with lyrics belted out by individual singers.🕜

Keeping with the Depot’s earlier World War II theme, a military hospital car was filled with bunks, a small operating theater, a nurse’s station, and other accruements one would expect to see in one of these. These cars were part of a military hospital train, which usually had sixteen coaches that included cars for infectious patients, doctors’ quarters, nurses’ quarters, a pharmacy, a kitchen and a mess. Most military trains carried around 375 beds but had no air conditioning, so pleasant they were not, especially in the hot months of the year. Nor did the jostling and bumping train as its traveled make the lives of those painful wounds any more comfortable. Oh, and then there were the flies and stench of gangrene and other noxious diseases the wounded often suffer from. Nurses worked twelve hour shifts (or longer) and among other duties tried to make patients as comfortable as possible.

One car was converted into an exhibit about Swing music, the most popular type in American throughout World War II. Although some music critics don’t consider Swing a subgenre of Jazz, a number of Jazzmen were in Swing bands and their influence is unmistakable. Two Swing bandleaders who the exhibit highlights are Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey. Even those who know nothing about Swing will have at some point have heard Goodman’s “Sing Sing Sing” because it’s been in so many movies. Tommy Dorsey’s song “Opus One” might not be as familiar, but it’s a perfect example of Swing music. I was surprised that examples of this music wasn’t playing in the background or available to hear in some way, but possibly there are rights issues and that is why none was to be found. You can go to a live mike in this car and sing your heart out. Swing fell out favor after World War II in part because the cost of running a big band (which usually had seventeen members) had gotten too expensive, and American public’s taste had shifted to preferring songs with lyrics belted out by individual singers.🕜

Most Pennsylvania Railroad trains stopped in Dennison to water and acquire coal for the steam engines. The yards employed nearly three thousand men year round and included an engine repair house, a round house, an ice house, a sand house, a waterworks, and a car repair shop. On July 17, 1918, it was announced that $1.5 million would be invested here that would, among other things, be used to modify the roundhouse to accommodate larger engines. This investment was made during the economic boom being caused by World War I. In 1921 a depression struck the United States that lasted into 1922, and, as a result, the workers at Dennison went on strike. The Pennsylvania Railroad responded by shutting the Dennison yards and all their shops down, causing the loss of almost 3,000 jobs.

Dennison was devastated and its population began to shrink as those who needed work went elsewhere to find it. Nearly 1,000 people left the village between 1920 and 1930. The only other major source of employment here at the time was the clay sewer pipe industry. Trains still stopped to water and coal, but in 1931 even that ended when these activities were done elsewhere. The mighty Pennsylvania Railroad ultimately faired no better than Dennison’s yards. By the 1950s it and most other American railroads were in decline, in part because the U.S. government decided to invest in highways and the Interstate system.

In 1968 the Pennsylvania Railroad merged with New York Central Railroad and out of this came the short-lived Penn Central Transportation Company. This went bankrupt in 1970 and in doing so changed the way railroads work in America forever. Before this time all railroads were required to have a passenger service, which the railroads hated because it was a money losing venture. So Congress intervened and a new national passenger service, Amtrak, was born. Penn Central and several other bankrupt companies were merged into the Consolidated Rail Corporation, better known as Conrail, whose assets were later purchased by Norfolk & Southern and CSX in 1997.

Dennison was devastated and its population began to shrink as those who needed work went elsewhere to find it. Nearly 1,000 people left the village between 1920 and 1930. The only other major source of employment here at the time was the clay sewer pipe industry. Trains still stopped to water and coal, but in 1931 even that ended when these activities were done elsewhere. The mighty Pennsylvania Railroad ultimately faired no better than Dennison’s yards. By the 1950s it and most other American railroads were in decline, in part because the U.S. government decided to invest in highways and the Interstate system.

In 1968 the Pennsylvania Railroad merged with New York Central Railroad and out of this came the short-lived Penn Central Transportation Company. This went bankrupt in 1970 and in doing so changed the way railroads work in America forever. Before this time all railroads were required to have a passenger service, which the railroads hated because it was a money losing venture. So Congress intervened and a new national passenger service, Amtrak, was born. Penn Central and several other bankrupt companies were merged into the Consolidated Rail Corporation, better known as Conrail, whose assets were later purchased by Norfolk & Southern and CSX in 1997.

The Dennison Depot did have a renaissance during World War II. At this time the U.S. airline industry was in its infancy, and American roads were not up to accommodating the sort of traffic needed to move millions of troops across North America to awaiting ships that would take them into action in foreign theaters of war. That left railroads as the only form of mass transit at the time capable of pulling this off. Thousands of troops just out of boot camp were stuffed on trains for sometimes very long trips across multiple states. There was one problem. The military lacked the capacity to feed them.

On New Year’s Eve in 1941, Mrs. Lucille Nussdorfer saw one of these troop trains stopped in Dennison and was moved by the sight of the young men riding on it whose faces betrayed loneliness and hunger. She determined to give the men some free food during their stops here, and to that end organized a servicemen’s canteen. It opened on March 21, 1942, initially in an office, then in a disused gas station. But so great was demand that she needed something larger, so permission was gotten from the Pennsylvania Railroad to open the depot to serve as the canteen.

The massive amounts of food needed—mostly cookies, coffee and sandwiches—was donated locally by farmers, citizens of nearby Sugar Creek, railroad unions, and anyone who could spare a bit. The canteen system was implemented across the United States but Dennison’s operation was by far the biggest. With 3,987 volunteers over its years of operation (a few of whom once got caught on a departing train, leading to them being forbidden to board them), the service ran twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week throughout the war. About twenty trains passed through each day, and some thirteen percent of all troop train traffic went through Dennison (1.5 millions soldiers).

No one person could handle such a volume, so Lucille asked the Salvation Army for help because it had the talent and resources coordinate this effort. Dennison Depot became known by passing soldiers as Dreamsville, U.S.A., in part because many of the volunteers were young ladies who reminded these men of their sisters and girlfriends from back home. It profoundly impacted both the volunteers and the troops who stopped here. One volunteer recalled that while serving men at the canteen she didn’t remember many faces but could remember all the hands reaching out for food. Even German POWs passing through were fed.

On New Year’s Eve in 1941, Mrs. Lucille Nussdorfer saw one of these troop trains stopped in Dennison and was moved by the sight of the young men riding on it whose faces betrayed loneliness and hunger. She determined to give the men some free food during their stops here, and to that end organized a servicemen’s canteen. It opened on March 21, 1942, initially in an office, then in a disused gas station. But so great was demand that she needed something larger, so permission was gotten from the Pennsylvania Railroad to open the depot to serve as the canteen.

The massive amounts of food needed—mostly cookies, coffee and sandwiches—was donated locally by farmers, citizens of nearby Sugar Creek, railroad unions, and anyone who could spare a bit. The canteen system was implemented across the United States but Dennison’s operation was by far the biggest. With 3,987 volunteers over its years of operation (a few of whom once got caught on a departing train, leading to them being forbidden to board them), the service ran twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week throughout the war. About twenty trains passed through each day, and some thirteen percent of all troop train traffic went through Dennison (1.5 millions soldiers).

No one person could handle such a volume, so Lucille asked the Salvation Army for help because it had the talent and resources coordinate this effort. Dennison Depot became known by passing soldiers as Dreamsville, U.S.A., in part because many of the volunteers were young ladies who reminded these men of their sisters and girlfriends from back home. It profoundly impacted both the volunteers and the troops who stopped here. One volunteer recalled that while serving men at the canteen she didn’t remember many faces but could remember all the hands reaching out for food. Even German POWs passing through were fed.

Entrance to the RR Car Section of the Musuem

Hospital Car

Communications Office

Assortment of Railroad Signals

Urichsville Block House

Dennison Trainyards (Model Railroad)

Homefront Living Room

Galley

Swing Music Exhibit