Fort Laurens Museum

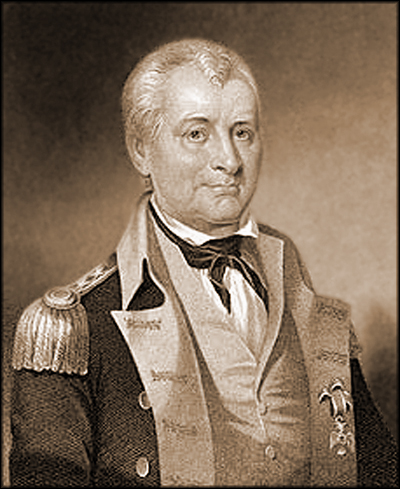

General Lachlin McIntosh

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Fort Laurens Museum

Items used by soldiers during the American Revolution.

Stone Bridge

Henry Laurens. Engraving by Valentine Green.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Artifacts from the American Revolution era.

British Soldier and Native American

Pennsylvania Solider

British Soldier

Stuffed Fox

Location of one the graves of Patriot soldiers found on the grounds of the fort.

Sometimes it’s the unexpected stuff that draws you to a place. One of my coworkers is part of a farm coop that sends out a magazine to members called Ohio Cooperative Living. In addition to covering coop business and issues, this magazine sometimes contains brief articles about Ohio’s history. My coworker loaned me the July 2023 issue so I could read an article about the death of Colonel William Crawford, who was burned at the stake by Wyandots on June 11, 1782.

It was just a few paragraphs, so after completing it, I flipped through the pages and found a calendar of upcoming events in Ohio for June and July 2023. One of them was a presentation by Alan Fitzpatrick at the theater in Fort Laurens Museum in Tuscarawas County called “History and Culture of Native Americans in the Ohio Country in the 18th Century.” This I wanted to see, so on a Saturday morning I drove two hours to reach it, bringing along with me two traveling companions.

Fort Laurens Museum is a small, circular building with its theater in the center, this room taking up most of the building’s space. The theater seats forty to fifty people, and it was packed. At first I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to hear because there was no PA system, but once everyone quieted down, it turned out not to be an issue.

It was just a few paragraphs, so after completing it, I flipped through the pages and found a calendar of upcoming events in Ohio for June and July 2023. One of them was a presentation by Alan Fitzpatrick at the theater in Fort Laurens Museum in Tuscarawas County called “History and Culture of Native Americans in the Ohio Country in the 18th Century.” This I wanted to see, so on a Saturday morning I drove two hours to reach it, bringing along with me two traveling companions.

Fort Laurens Museum is a small, circular building with its theater in the center, this room taking up most of the building’s space. The theater seats forty to fifty people, and it was packed. At first I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to hear because there was no PA system, but once everyone quieted down, it turned out not to be an issue.

Fitzpatrick has studied and written about the history of Ohio’s Native Americans for many years. He said that keepers of Ohio tribal histories rarely speak about it to outsiders, and he was lucky that he gained the trust of a Wyandot historian who did open up to him about certain topics. Ohio’s Native American tribes were nearly wiped out, then forcibly removed by Andrew Jackson, so they’re understandably weary about dealing with whites to this day. In the 1750s, for example, there were about 20,000 Wyandots in Ohio, and by the time they were forcibly deported in 1843, there were 400 of them left. Fitzpatrick made it a point to say that he was “painting a broad brush” when speaking about Ohio’s indigenous people, meaning that he was doing generalizations. Much of what he relayed was specific to the Wyandots, although other Ohio tribes had more in common with their culture than not.

From about 1640 to 1701, Ohio was virtually empty of settled peoples. The Iroquois (a confederation of five and later six tribes that called themselves the Haudenosaunee) pushed them out so as to preserve the wilderness for the procurement of furs. The Iroquois couldn’t maintain this state of affairs, so in 1701 they signed the Treaty of Grande Paix that ended the fighting. This agreement was between them, the indigenous people they’d pushed out of the Ohio Country, Britain, and France. The treaty was codified with wampum belts, the design of which was the equivalent of a written document.

Afterwards many of the displaced Native Americans, most of them Algonquian speakers, returned to Ohio. This included the Wyandots, who were remnants of the destroyed Huron-Wendat tribe, Shawnees, and the Lenape, who the English called Delawares—a people who were pushed out their original homeland in what is today New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York. Seneca-Cayugas also settled in Ohio. Having been part the Iroquois Confederation, they’d left, and their group became known as Mingos, an ethnic slur.

From about 1640 to 1701, Ohio was virtually empty of settled peoples. The Iroquois (a confederation of five and later six tribes that called themselves the Haudenosaunee) pushed them out so as to preserve the wilderness for the procurement of furs. The Iroquois couldn’t maintain this state of affairs, so in 1701 they signed the Treaty of Grande Paix that ended the fighting. This agreement was between them, the indigenous people they’d pushed out of the Ohio Country, Britain, and France. The treaty was codified with wampum belts, the design of which was the equivalent of a written document.

Afterwards many of the displaced Native Americans, most of them Algonquian speakers, returned to Ohio. This included the Wyandots, who were remnants of the destroyed Huron-Wendat tribe, Shawnees, and the Lenape, who the English called Delawares—a people who were pushed out their original homeland in what is today New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York. Seneca-Cayugas also settled in Ohio. Having been part the Iroquois Confederation, they’d left, and their group became known as Mingos, an ethnic slur.

One thing these native peoples had in common was their decentralized governments. Tribes were divided into clans, and each one had its own chief who only spoke for that clan. This confused the English and later Americans because they couldn’t understand why making peace with one chief didn’t include the entire tribe. None of the tribes believed that an individual could own a piece of land, but that didn’t mean they didn’t collectively consider the parts of Ohio they controlled as theirs.

These tribes were matriarchal, so they were governed by women, who named the children and it was their clans that a child belonged to. After marriage, a husband moved in with his wife’s family, and if the couple divorced, the ex-husband was kicked out without much to show for it. A council of elder women picked the clan chief, although not the war chief. War chiefs were chosen by the men, who were expected to hunt and fight. A war chief was considered successful if a war party he’d led returned with few or no dead.

Disease and war had so decimated Ohio’s native people that their women mandated that when their men made war, they returned with prisoners so they could be considered for adoption into the tribe to incrwase its size. Those captives not adopted were often ransomed—another decision made by the women—although those deemed a danger to the tribe were killed outright.

These tribes were matriarchal, so they were governed by women, who named the children and it was their clans that a child belonged to. After marriage, a husband moved in with his wife’s family, and if the couple divorced, the ex-husband was kicked out without much to show for it. A council of elder women picked the clan chief, although not the war chief. War chiefs were chosen by the men, who were expected to hunt and fight. A war chief was considered successful if a war party he’d led returned with few or no dead.

Disease and war had so decimated Ohio’s native people that their women mandated that when their men made war, they returned with prisoners so they could be considered for adoption into the tribe to incrwase its size. Those captives not adopted were often ransomed—another decision made by the women—although those deemed a danger to the tribe were killed outright.

Fitzpatrick’s presentation lasted just over an hour, and it was excellent. The same can’t be said about the museum itself. I never mind paying to see a museum, but here I didn’t get my money’s worth. There isn’t much to see, and it’s unlikely to take any more than half an hour to go through. Its life sized sculptures aren’t bad (save for the one that my brother pointed out looked like a Klingon), but they’ve seen better days. The museum was built in 1971 and it’s probable the sculptures were made at this time. It shows: they’re in need of some serious restoration. The pity of it is that the same people who run this museum also curate the far superior Zoar Village, so I’d say the issue of its quality is money—or the lack thereof.

Archeological digs were done on Fort Laurens site in 1972, 1984 and 1986. These yielded quite a few artifacts, but they mostly consisted of the trash left behind by the departing soldiers. While these bits and bobs are important to archeologists to tell the story of the fort’s brief existence, it doesn’t mean they should be put on display like they have been. It’s the equivalent of exhibiting tabs from beer cans or a rusted corkscrew.

The museum does have well written and quite informative information signs both outside on the grounds and inside the museum proper. Fort Laurens is notable for being the only Revolutionary War fort built by the Continental Army in what is today Ohio. During the war it was part of the Ohio country, an area encompassing the current state as well as some of western Pennsylvania and a bit of eastern Indiana.

Archeological digs were done on Fort Laurens site in 1972, 1984 and 1986. These yielded quite a few artifacts, but they mostly consisted of the trash left behind by the departing soldiers. While these bits and bobs are important to archeologists to tell the story of the fort’s brief existence, it doesn’t mean they should be put on display like they have been. It’s the equivalent of exhibiting tabs from beer cans or a rusted corkscrew.

The museum does have well written and quite informative information signs both outside on the grounds and inside the museum proper. Fort Laurens is notable for being the only Revolutionary War fort built by the Continental Army in what is today Ohio. During the war it was part of the Ohio country, an area encompassing the current state as well as some of western Pennsylvania and a bit of eastern Indiana.

In 1777, the British began pressuring Ohio’s indigenous peoples to abandon neutrality and fight against the colonists. The British argued that by going to war against the colonists, Ohio’s indigenous people could retake land stolen by them. The British also offered to arm and supply Ohio’s native peoples. At first the tribes resisted getting involved, but it didn’t take long before that changed. The Shawnees, for example, abandoned neutrality when Virginians murdered Chief Cornstalk at Fort Randolph on November 10, 1777. Open warfare between the Wyandots, Seneca-Cayugas, and Shawnees erupted the next year. The Lenape allied with the colonists.

At the beginning of 1778, Congress conceived of a plan to build a series of forts in the Ohio Country that would allow the Continental Army to attack Detroit as well as subdue hostile Native Americans. To this end, a force of about 1,000 Virginian and Pennsylvanian regulars and militia men set out from Fort Pitt (modern Pittsburgh) on October 23, 1778. They built their first fortification along the Ohio River in what is today Beaver, Pennsylvania, and named it after their expedition commander, General Lachlin McIntosh.

This fort would serve as a supply depot, supplies being something the Continental Army and colonial militias were chronically short of throughout the entirety of the war. Heading across the Ohio River into Ohio proper, McIntosh’s force found it going slow because thick, untamed wilderness is not easy to penetrate. McIntosh stopped at the Tuscarawas River in Delaware territory and here decided to build another fort on the spot where British colonel Henry Bouquet had erected one during the French and Indian War.

At the beginning of 1778, Congress conceived of a plan to build a series of forts in the Ohio Country that would allow the Continental Army to attack Detroit as well as subdue hostile Native Americans. To this end, a force of about 1,000 Virginian and Pennsylvanian regulars and militia men set out from Fort Pitt (modern Pittsburgh) on October 23, 1778. They built their first fortification along the Ohio River in what is today Beaver, Pennsylvania, and named it after their expedition commander, General Lachlin McIntosh.

This fort would serve as a supply depot, supplies being something the Continental Army and colonial militias were chronically short of throughout the entirety of the war. Heading across the Ohio River into Ohio proper, McIntosh’s force found it going slow because thick, untamed wilderness is not easy to penetrate. McIntosh stopped at the Tuscarawas River in Delaware territory and here decided to build another fort on the spot where British colonel Henry Bouquet had erected one during the French and Indian War.

Construction began in Fall 1778. French military engineer Colonel Jean Louis Cambray-Digny designed the fort. (Oddly, one museum information sign says he’s French, another Italian. He was French.) Much of the construction work was done by the 8th Pennsylvanian Regiment.

McIntosh named the new fortification Fort Laurens in honor of his good friend Henry Laurens, the fifth president of the Continental Congress. Laurens was from South Carolina, McIntosh from Georgia, and both were invested in the slave culture of the region. Laurens served as the Continental Congress’ president from November 1777 to December 1778. After stepping down, he was made Minister to the Netherlands.

While traveling back home, the Royal Navy captured his ship and took him prisoner. He was a guest in the Tower of London for the next fifteen months and, an information sign says, “the only American ever imprisoned there.” He was exchanged for none other than Lord Charles Cornwallis, the general Washington defeated at Yorktown. After his release, Laurens went to Paris as part of the American team that negotiated the treaty that formally ended the war. After his death on December 8, 1792, Laurens was cremated, and this was the “the first formal cremation in the United States.”

McIntosh envisioned Fort Laurens as a place from which he could attack hostile Native Americans and as a western supply post for the planned (or really hoped for) assault on Detroit. After completing it, he returned to Fort McIntosh with all but 176 men. What supplies this little garrison had soon run out, forcing it to boil moccasins and ox-hides to make soup. The men called the place “Fort Nonsense.

McIntosh named the new fortification Fort Laurens in honor of his good friend Henry Laurens, the fifth president of the Continental Congress. Laurens was from South Carolina, McIntosh from Georgia, and both were invested in the slave culture of the region. Laurens served as the Continental Congress’ president from November 1777 to December 1778. After stepping down, he was made Minister to the Netherlands.

While traveling back home, the Royal Navy captured his ship and took him prisoner. He was a guest in the Tower of London for the next fifteen months and, an information sign says, “the only American ever imprisoned there.” He was exchanged for none other than Lord Charles Cornwallis, the general Washington defeated at Yorktown. After his release, Laurens went to Paris as part of the American team that negotiated the treaty that formally ended the war. After his death on December 8, 1792, Laurens was cremated, and this was the “the first formal cremation in the United States.”

McIntosh envisioned Fort Laurens as a place from which he could attack hostile Native Americans and as a western supply post for the planned (or really hoped for) assault on Detroit. After completing it, he returned to Fort McIntosh with all but 176 men. What supplies this little garrison had soon run out, forcing it to boil moccasins and ox-hides to make soup. The men called the place “Fort Nonsense.

Things got worse. From Detroit, British captain Henry Bird and ten men brought gifts to the Native Americans in Sandusky to entice them to attack Fort Laurens. It worked. Led by John Montour and Simon Girty, a force of 180 Shawnees, Mingos, Wyandots, Muncies, and four Delawares laid siege to the fort. To “prove” his garrison was well-supplied, Colonel Gibson gave the attackers a barrel of flour. This didn’t deter them, so here they stayed until being run off by a colonial relief expedition on March 23, 1779. Twenty-one Americans died here. A mass grave of men gathering firewood who were ambushed and killed here was unearthed in 1986. Their remains were transferred to a crypt inside the museum proper.

Being a Southerner, McIntosh wasn’t especially popular with the Pennsylvanians, so he asked for a transfer. Colonel Daniel Brodhead replaced him. He didn’t think much of Fort Laurens location—it was too far away to supply—so he asked General Washington if it could be abandoned. Washington agreed. The last of its garrison departed on August 2, 1779.

Over decades the fort slowly decayed. In 1828 two of its bastions were destroyed to make way for the Ohio and Erie Canal. Only a faint outline of the fort remained in 1850, explaining why Charles Whittlesey’s map done in that year put it at the wrong location. The last usable parts of the Ohio and Erie Canal were destroyed in 1913 by a massive flood. In the 1960s, part of Interstate 77 was built along its remains. The section of the Tuscarawas River that the fort stood by was rerouted to accommodate the new interstate. This has the upside of making the fort’s location easier to access.🕜

Being a Southerner, McIntosh wasn’t especially popular with the Pennsylvanians, so he asked for a transfer. Colonel Daniel Brodhead replaced him. He didn’t think much of Fort Laurens location—it was too far away to supply—so he asked General Washington if it could be abandoned. Washington agreed. The last of its garrison departed on August 2, 1779.

Over decades the fort slowly decayed. In 1828 two of its bastions were destroyed to make way for the Ohio and Erie Canal. Only a faint outline of the fort remained in 1850, explaining why Charles Whittlesey’s map done in that year put it at the wrong location. The last usable parts of the Ohio and Erie Canal were destroyed in 1913 by a massive flood. In the 1960s, part of Interstate 77 was built along its remains. The section of the Tuscarawas River that the fort stood by was rerouted to accommodate the new interstate. This has the upside of making the fort’s location easier to access.🕜