Fort Pitt

Fort Pitt Museum Entrance

Inside the Fort Pitt Museum

A replica scene of work being done in one of Fort Pitt's underground locations.

Fort Dusquesne Diorama

The Fort Pitt blockhouse is the only part of the original fort to survive.

Fort Pitt Barracks

Lenape (Delaware) Chief Tamaqua was a diplomat who helped negotiated the peace between Native Americans and the British at the end of the French & Indian War and Pontiac's Rebellion.

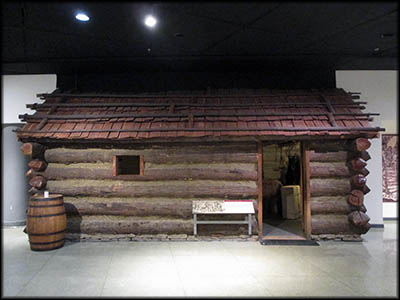

Log cabins like this surrounded the area around Fort Pitt and were often used by fur traders.

This Fort Pitt diorama was created by Stotz, a team that worked for the local company Holiday Displays, which was known for making store window displays in department stores.

General Jeffrey Amherst

Portrait by Thomas Gainsborough (1785)

Wikimedia Commons

Portrait by Thomas Gainsborough (1785)

Wikimedia Commons

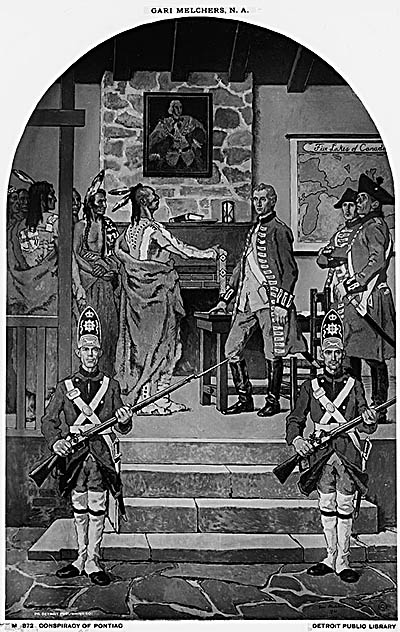

"Conspiracy of Pontiac" by Gari Melchers

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

I have a complete inability to pronounce French names without hearing someone speak them first. Even then my enunciations are iffy. When I came across the name “Fort Duquesne,” I immediately went to YouTube to find someone pronouncing it. Somehow, I misunderstood what I heard and thought “Duquesne” was pronounced “Dunsk.” During my visit to its former location in Pittsburgh, my friend pronounced it “Do-Caine” (rhymes with clue-sane), and that’s when I learned that I’d had was saying the name spectacularly wrong. So what does this have to do with the Fort Pitt Museum? Fort Duquesne and Fort Pitt were both built in what is now Pittsburgh at the place where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet to form the Ohio, which was known in the eighteenth century as the Point or Forks.

In 1750 its strategic importance became paramount. In that year King George II granted the Ohio Company of Virginia 200,000 acres of land in what is now Western Pennsylvania with the proviso that the land be sold to a minimum of 100 families that Christopher Gist spent the next three years surveying. The trouble was France also claimed the region, known as the Ohio County. France valued the region for its lucrative bounty of furs and hides, as did a third power that asserted control, the Iroquois Confederation. France decided to reinforce its ownership by building a series of forts in the Ohio Country. This greatly alarmed the British government, which told its colonial governors to do something about it. Virginia’s lieutenant governor, Robert Dinwiddie, sent a twenty-one-year-old Virginian surveyor, George Washington, to tell the French that they needed to immediately depart from the region.

In 1750 its strategic importance became paramount. In that year King George II granted the Ohio Company of Virginia 200,000 acres of land in what is now Western Pennsylvania with the proviso that the land be sold to a minimum of 100 families that Christopher Gist spent the next three years surveying. The trouble was France also claimed the region, known as the Ohio County. France valued the region for its lucrative bounty of furs and hides, as did a third power that asserted control, the Iroquois Confederation. France decided to reinforce its ownership by building a series of forts in the Ohio Country. This greatly alarmed the British government, which told its colonial governors to do something about it. Virginia’s lieutenant governor, Robert Dinwiddie, sent a twenty-one-year-old Virginian surveyor, George Washington, to tell the French that they needed to immediately depart from the region.

Washington was chosen in part because some of his family members had investments in the Ohio Company, but mostly because he’d survey much of the area for Lord Thomas Fairfax. Despite not speaking a word of French, in 1743 he along with interpreter Jacon Van Braam headed northwest to Fort de la Rivière au Bœuf (now Waterford, Pennsylvania). Along the way the two stopped at the Native American village Logstown (modern Aliquippa, Pennsylvania) and there paid four Senecas—Chiefs White and Jeskakake, Tanaghrisson, and a hunter named Guyasuta—to serve as an escort. Senecas were part of the Iroquois Confederation, a staunch British ally. At Fort la Bœuf, the French listened what Washington had to say, then told him they were going staying put.

In February of the next year, Captain William Trent—an investor in the Ohio Company—led forty men to the Point to build a fort. He was accompanied by a contingent of Iroquois led by Tanaghrisson, who personally laid down the first log and proclaimed that the new fortification belonged to both the English and Iroquois. It was christened Fort Prince George. Construction was underway when a force of 500 French soldiers arrived on April 17. They informed the Virginians it was in their best interest to leave, which they did.

In February of the next year, Captain William Trent—an investor in the Ohio Company—led forty men to the Point to build a fort. He was accompanied by a contingent of Iroquois led by Tanaghrisson, who personally laid down the first log and proclaimed that the new fortification belonged to both the English and Iroquois. It was christened Fort Prince George. Construction was underway when a force of 500 French soldiers arrived on April 17. They informed the Virginians it was in their best interest to leave, which they did.

Here the French built Fort Duquesne. On the same weekend that I visited Fort Pitt, I also ventured to Fort Necessity, where I learned how George Washington started the French and Indian War, or Seven Years’ War, by attacking a smaller French force for no good reason. Instead of retreating, he stayed put and built Fort Necessity. It wasn’t a well-made or well-positioned fortification, so when French did attack, they bested Washington and his men.

Nearly a year later, Washington joined a British army led by General Edward Braddock whose goal was to capture Fort Duquesne. It didn’t go well for the British. Braddock was killed and his men routed by a much smaller French force and its Native American allies. In 1757, another British army headed for Fort Duquesne once more with the same goal as before. Before reaching it, the French abandoned and burned it down. A more detailed version of this story can be found in my travel log about Fort Necessity.

The American part of the Seven Years’ War ended in in 1758 when France’s Native American allies made peace with the British with the Treaty of Easton. In exchange for this peace, the British pledged to stay on the eastern side of the Appalachians. It wasn’t a promise easily kept.

Nearly a year later, Washington joined a British army led by General Edward Braddock whose goal was to capture Fort Duquesne. It didn’t go well for the British. Braddock was killed and his men routed by a much smaller French force and its Native American allies. In 1757, another British army headed for Fort Duquesne once more with the same goal as before. Before reaching it, the French abandoned and burned it down. A more detailed version of this story can be found in my travel log about Fort Necessity.

The American part of the Seven Years’ War ended in in 1758 when France’s Native American allies made peace with the British with the Treaty of Easton. In exchange for this peace, the British pledged to stay on the eastern side of the Appalachians. It wasn’t a promise easily kept.

The British built a new fortification beside the ruins of Duquesne called Fort Pitt, named in honor of British statesman William Pitt the Elder. Fort Pitt would serve a place of offense, defense, diplomacy, and trade. Here, too, a civilian settlement began to grow into what is today Pittsburgh. Upon its completion, Fort Pitt was, according to a museum information sign, “Britain’s most heavily defended fort west of the Allegheny Mountains.” In just a few years that would be put to the test.

Of it, nothing save for a brick blockhouse remains. Built in 1764 as a redoubt (a place of defense outside the fort’s walls), the blockhouse served many functions after the fort’s demise, including that of a residence. Neglected and at once point surrounded by a slum, in 1894 it was given to the Daughters of the American Revolution and Allegheny County, who restored it. The day I visited it was temporarily closed to accommodate a wedding, so I didn’t peak inside.

The British failed to keep their word to keep their colonists east of the Appalachians, angering Native Americans. Making matters, the new British commander-in-chief of North American forces, General Jeffrey Amherst, forbade the trading of lead, gunpowder and alcohol with the indigenous peoples in the colonies. They were often prevented from hunting on their traditional grounds, causing famine. Outraged, Ottawa chief Pontiac rallied a coalition of Native Americans allies—some of whom had been enemies of one another—and launched a campaign to remove the colonial incursion.

Of it, nothing save for a brick blockhouse remains. Built in 1764 as a redoubt (a place of defense outside the fort’s walls), the blockhouse served many functions after the fort’s demise, including that of a residence. Neglected and at once point surrounded by a slum, in 1894 it was given to the Daughters of the American Revolution and Allegheny County, who restored it. The day I visited it was temporarily closed to accommodate a wedding, so I didn’t peak inside.

The British failed to keep their word to keep their colonists east of the Appalachians, angering Native Americans. Making matters, the new British commander-in-chief of North American forces, General Jeffrey Amherst, forbade the trading of lead, gunpowder and alcohol with the indigenous peoples in the colonies. They were often prevented from hunting on their traditional grounds, causing famine. Outraged, Ottawa chief Pontiac rallied a coalition of Native Americans allies—some of whom had been enemies of one another—and launched a campaign to remove the colonial incursion.

Known today as Pontiac’s Rebellion, this is not an accurate appellation. A war is only a rebellion if those who start it accept the overlordship of another—which they didn’t. So really this conflict ought to be called Pontiac’s War of Liberation. Although it began near Fort Detroit, it spread all across the Great Lake’s region, causing settlers in western Pennsylvania to flee to Fort Pitt for protection. Other British forts fell to Native American attackers or were abandoned. Contact with the east was effectively cut off.

Shawnees and Lenapes (Delawares) laid siege to Fort Pitt. Its commandant, Colonel Henry Bouquet, was in the Philadelphia at the time. Amherst sent him troops and from the city he led the force, which included Highlanders, to restore communication with western outposts. His army was attacked a mile east of Bushy Run Station in Westmoreland County. After spending a night behind an improvised fort made out of flour bags, in the morning Highlanders led a counterattack that soundly defeated the enemy. Many of the Native American warriors here had come from the siege of Fort Pitt and didn’t return. Bouquet did, ending the crisis.

When I visited the museum there was a temporary exhibit about the life of Guyasuta, one of the four Senecas who’d accompanied Washington to Fort la Bœuf. During the French and Indian War, Guyasuta became disaffected with the Iroquois Confederation and like many others from that alliance, broke away and became part of a group of defectors known as the Mingos. They allied themselves with the French during the Seven Years’ War.

Shawnees and Lenapes (Delawares) laid siege to Fort Pitt. Its commandant, Colonel Henry Bouquet, was in the Philadelphia at the time. Amherst sent him troops and from the city he led the force, which included Highlanders, to restore communication with western outposts. His army was attacked a mile east of Bushy Run Station in Westmoreland County. After spending a night behind an improvised fort made out of flour bags, in the morning Highlanders led a counterattack that soundly defeated the enemy. Many of the Native American warriors here had come from the siege of Fort Pitt and didn’t return. Bouquet did, ending the crisis.

When I visited the museum there was a temporary exhibit about the life of Guyasuta, one of the four Senecas who’d accompanied Washington to Fort la Bœuf. During the French and Indian War, Guyasuta became disaffected with the Iroquois Confederation and like many others from that alliance, broke away and became part of a group of defectors known as the Mingos. They allied themselves with the French during the Seven Years’ War.

Even before the war officially ended, Guyasuta tried to rally the indigenous people to gather in force and push the British west of the Appalachians. He was one of the leaders of Pontiac’s war against the British, and he participated both in the siege of Pittsburg and the battle at Bushy Run. When then war ended without the desired outcome, he, according to an information sign, “shifted his focus to obtaining a fair settlement for his people, reopening the fur trade on which they depended, and restoring peace to the region.”

Fort Pitt became the heart of the fur and hide trade. White-tailed deer, for example, were used to create leather breeches, while the fur from otters, beavers, foxes and raccoons was used for making items of clothing such as hats. Native Americans hunted and brought the hides and fur to local traders in exchange for European goods such as guns, gunpowder, and alcohol.

During this period Guyasuta busied himself with travel thousand of miles as a roving diplomat. In Autumn 1770, he encountered George Washington along the Ohio River. He also visited Philadelphia, there witnessing an electric experiment. The information sign mentioning this wasn’t forthcoming as to what that involved. He later fought against the Americans during the Revolution.

The British abandoned Fort Pitt in 1772 because it was too expensive to keep. They also hoped its closure would foster better relations with Native Americans west of the Allegany Mountains. Floods and age had left the fort reduced to a ruin of its original state. The British sold it to William Thompson and Alexander Ross, whose efforts to dismantle and sell off the materials from which it was built such as bricks, lumber and iron, was put on hold when Virginia’s governor, Lord Dunmore, started a small war against the Shawnees and Mingos in 1774. Dunmore also wanted to assert Virginia’s claim on Pittsburgh and to that end had Fort Pitt occupied and renamed after himself. The next year the War of Independence started, and the rebellious colonists appropriated fortress for themselves, restoring its name to Fort Pitt. The Americans officially decommissioned it in 1792.🕜

Fort Pitt became the heart of the fur and hide trade. White-tailed deer, for example, were used to create leather breeches, while the fur from otters, beavers, foxes and raccoons was used for making items of clothing such as hats. Native Americans hunted and brought the hides and fur to local traders in exchange for European goods such as guns, gunpowder, and alcohol.

During this period Guyasuta busied himself with travel thousand of miles as a roving diplomat. In Autumn 1770, he encountered George Washington along the Ohio River. He also visited Philadelphia, there witnessing an electric experiment. The information sign mentioning this wasn’t forthcoming as to what that involved. He later fought against the Americans during the Revolution.

The British abandoned Fort Pitt in 1772 because it was too expensive to keep. They also hoped its closure would foster better relations with Native Americans west of the Allegany Mountains. Floods and age had left the fort reduced to a ruin of its original state. The British sold it to William Thompson and Alexander Ross, whose efforts to dismantle and sell off the materials from which it was built such as bricks, lumber and iron, was put on hold when Virginia’s governor, Lord Dunmore, started a small war against the Shawnees and Mingos in 1774. Dunmore also wanted to assert Virginia’s claim on Pittsburgh and to that end had Fort Pitt occupied and renamed after himself. The next year the War of Independence started, and the rebellious colonists appropriated fortress for themselves, restoring its name to Fort Pitt. The Americans officially decommissioned it in 1792.🕜