Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter Today

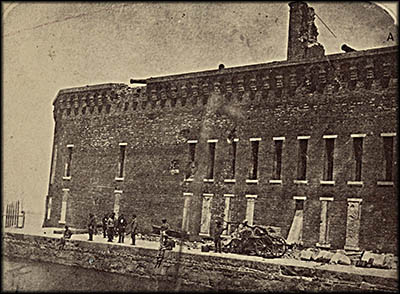

Fort Sumter April 1861

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

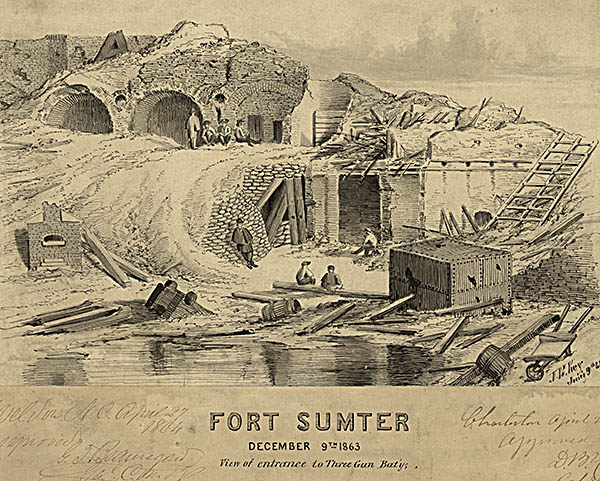

Fort Sumter December 1863. Library of Congress

Thomas Sumter

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

The present day Fort Sumter barely resembles how it looked during the opening days of the Civil War. There are few hints here and there of what was and you’re standing on the same ground, but most of what you see was built long after the Civil War ended. For that matter, there isn’t all that much there: just some brick walls and a few cannon that weren’t the ones present between 1861 and 1865.

The fort is free to visit but getting there isn’t. You have to take a ferry. There are two places you can get one: Patriots Point and Liberty Square Visitor Education Center, the latter having more departure times than the former. My traveling companions and I arrived on the first ferry of the day, allowing us to witness the raising of the flag during which a park ranger spoke about the fort’s history to the gathered crowd. You have a bit over an hour before the ferry departs, though I suppose if want to see every last brick and read every sign in the small but informative museum, you could stay longer and take the next ferry back. No one would notice or care.

Had the Confederates not aimed the first shot of the Civil War at Fort Sumter, it’s likely most Americans would know nothing about it. Who, for example, can tell you one thing about its contemporary, Fort Carroll, in Baltimore Harbor other than people who live in that city or historians specializing in old American military installations? Sumter was just one of many forts constructed after the War of 1812 by the United States along the Atlantic Coast as part of its defenses against foreign invaders. It along with nearby Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island and several other places with strategically placed artillery were designed to keep hostile ships from entering Charleston Harbor.

The fort was named after South Carolinian Revolutionary war hero and statesman General Thomas Sumter. Construction began in 1829. It didn’t go well. For one, the island upon which it stands had to be created artificially using about 70,000 tons of granite, most of it imported from the North. Funding periodically ran out, stopping work. The fort was five-sided and made of bricks, which by the outbreak of the Civil War, masonry walls were useless against the artillery pieces of the day. Sumter was supposed to have 135 guns and 650 men, but in 1860 it had just 65 guns and a compliment of 85 soldiers, and it was still under construction.

Shortly after forming a new government under the U.S. Constitution, Congress passed a law that forbade the importation of slaves into the United States. The ban started in 1808. This didn’t stop smugglers. In 1858, the U.S. Navy captured the slave ship Echo and brought her into Charleston Harbor. She had left Africa with 450 live captives, mostly children and teenagers, and arrived with a mere 306 still living. It’s well known just how poorly slavers treated their captives, but the crew of the Echo were especially cruel. Refusing to feed their prisoners a sufficient amount of food, they were emaciated. Some of them were taken to Castle Pickney, others to Fort Sumter. They continued to die in both places. Ghoulishly, tours were arranged for Charlestonians to take a look at these abused souls at Fort Sumter, which, surprisingly, made a few pro-slavery onlookers decide the illegal business of importing slaves was outrageous and needed to be stopped.

The fort was named after South Carolinian Revolutionary war hero and statesman General Thomas Sumter. Construction began in 1829. It didn’t go well. For one, the island upon which it stands had to be created artificially using about 70,000 tons of granite, most of it imported from the North. Funding periodically ran out, stopping work. The fort was five-sided and made of bricks, which by the outbreak of the Civil War, masonry walls were useless against the artillery pieces of the day. Sumter was supposed to have 135 guns and 650 men, but in 1860 it had just 65 guns and a compliment of 85 soldiers, and it was still under construction.

Shortly after forming a new government under the U.S. Constitution, Congress passed a law that forbade the importation of slaves into the United States. The ban started in 1808. This didn’t stop smugglers. In 1858, the U.S. Navy captured the slave ship Echo and brought her into Charleston Harbor. She had left Africa with 450 live captives, mostly children and teenagers, and arrived with a mere 306 still living. It’s well known just how poorly slavers treated their captives, but the crew of the Echo were especially cruel. Refusing to feed their prisoners a sufficient amount of food, they were emaciated. Some of them were taken to Castle Pickney, others to Fort Sumter. They continued to die in both places. Ghoulishly, tours were arranged for Charlestonians to take a look at these abused souls at Fort Sumter, which, surprisingly, made a few pro-slavery onlookers decide the illegal business of importing slaves was outrageous and needed to be stopped.

Some called for the captives to be sold into slavery, but President James Buchanan, in one of the few times he did the right thing, ordered these victims of kidnapping to be returned to their homeland because to do otherwise violated the Constitution. They were sent to Monrovia, Liberia, on the steamer Niagara. Only 196 of the original 450 made it there alive.

The crew of the Echo was charged with piracy, a hanging offense. Despite an 1820 law outlining this, Judge Andrew G. Magrath ruled that kidnapping Africans for slavery wasn’t piracy and let the crew go. The Echo’s captain, Edward Townsend, was tried separately in Key West, Florida. Here a judge decided that since he didn’t own the ship, he could go free.

In late 1860, the U.S. Army appointed Major Robert Anderson to command federal troops in Charleston. He arrived on November 15. Despite being from Kentucky and thus a Southerner, he did his duty. Evaluating the situation at hand, he realized the growing hostility of Charlestonians towards he and his men would likely erupt into violence. After South Carolina seceded from the United States on December 20, Anderson decided Fort Moultrie was too exposed. During the night of December 26, he moved his troops to the more defensible Fort Sumter. Medical and other supplies as well as forty-five of his men’s wives and children followed.

In January 1861 President Buchanan sent the unarmed ship Star of the West to resupply the fort because it had just four months’ worth of food. As she entered Charleston Harbor, cadets from the military academy known as the Citadel fired upon her, forcing her to turn back. Anderson evacuated the women and children in his charge to New York. On April 11, 1861, Confederate general Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, who was once Anderson’s student, arrived at Fort Sumter under a white flag asking for its surrender. If Anderson refused, would destroy it. Anderson declined. Beauregard’s aids made a second attempt to convince Anderson to surrender, but he wouldn’t.

The crew of the Echo was charged with piracy, a hanging offense. Despite an 1820 law outlining this, Judge Andrew G. Magrath ruled that kidnapping Africans for slavery wasn’t piracy and let the crew go. The Echo’s captain, Edward Townsend, was tried separately in Key West, Florida. Here a judge decided that since he didn’t own the ship, he could go free.

In late 1860, the U.S. Army appointed Major Robert Anderson to command federal troops in Charleston. He arrived on November 15. Despite being from Kentucky and thus a Southerner, he did his duty. Evaluating the situation at hand, he realized the growing hostility of Charlestonians towards he and his men would likely erupt into violence. After South Carolina seceded from the United States on December 20, Anderson decided Fort Moultrie was too exposed. During the night of December 26, he moved his troops to the more defensible Fort Sumter. Medical and other supplies as well as forty-five of his men’s wives and children followed.

In January 1861 President Buchanan sent the unarmed ship Star of the West to resupply the fort because it had just four months’ worth of food. As she entered Charleston Harbor, cadets from the military academy known as the Citadel fired upon her, forcing her to turn back. Anderson evacuated the women and children in his charge to New York. On April 11, 1861, Confederate general Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, who was once Anderson’s student, arrived at Fort Sumter under a white flag asking for its surrender. If Anderson refused, would destroy it. Anderson declined. Beauregard’s aids made a second attempt to convince Anderson to surrender, but he wouldn’t.

On the morning on April 12 at 4:30, the first shot of the Civil War was fired at Fort Sumter from Fort Johnson on James Island. For the next thirty-four hours Sumter was bombarded, although it did fire back. Charlestonians watched the spectacle as if it were a Fourth of July event. Considerable damage, fires, plus low ammunition and food compelled Anderson to surrender. Union soldiers evacuated on April 14. The Confederates quickly occupied the fort.

For the next two years Charleston suffered from a blockade but otherwise went about its business. In 1863 that changed. A decision was made to take Morris Island from which the Union could attack Sumter. When a direct attack against Fort Wagner on the island’s northern end failed on July 18, the Union changed tactics and bombarded it for two months until it surrendered. Once in Union hands, rifled cannons were brought up and placed at Cummings Point from which they were fired at Sumter. Its walls were reduced to rubble that was piled up by slaves reinforced by sandbags, cotton bales, and similar items.

The fort proved impossible for the Union to reoccupy. On April 7, 1863, nine ironclad ships were sent to attack but return fire from the fort itself as well as shots from nearby Confederate-occupied Fort Moultrie and batteries located on Morris and Sullivan’s Island caused the fleet to retreat after just two hours. On the night of September 8, 1863, the Union launched an amphibious assault on the fort that ended in failure and resulted in the death, wounding or capture of 124 Union men. From 1863 until the end of the war, an estimated 43,000 shells weighing about seven million pounds hit the fort, leaving it an unrecognizable ruin by the time the South surrendered in 1865.

The rubble just sat there until 1870 when Quincy A. Gillmore, whose gunners had done most of the damage, was ordered the clean the place up. This effort lasted until 1876 when money for the project ran out. In 1899 two 12-inch breech-loading guns were emplaced on a new structure called Battery Huger, the main building visitors see today in which the museum resides. In 1943 these guns became scrap metal and were replaced by 90-mm artillery. The fort was decommissioned as a military site in 1947 and transferred to the National Park Service. It became a national monument the next year.🕜

The fort proved impossible for the Union to reoccupy. On April 7, 1863, nine ironclad ships were sent to attack but return fire from the fort itself as well as shots from nearby Confederate-occupied Fort Moultrie and batteries located on Morris and Sullivan’s Island caused the fleet to retreat after just two hours. On the night of September 8, 1863, the Union launched an amphibious assault on the fort that ended in failure and resulted in the death, wounding or capture of 124 Union men. From 1863 until the end of the war, an estimated 43,000 shells weighing about seven million pounds hit the fort, leaving it an unrecognizable ruin by the time the South surrendered in 1865.

The rubble just sat there until 1870 when Quincy A. Gillmore, whose gunners had done most of the damage, was ordered the clean the place up. This effort lasted until 1876 when money for the project ran out. In 1899 two 12-inch breech-loading guns were emplaced on a new structure called Battery Huger, the main building visitors see today in which the museum resides. In 1943 these guns became scrap metal and were replaced by 90-mm artillery. The fort was decommissioned as a military site in 1947 and transferred to the National Park Service. It became a national monument the next year.🕜

Inside Fort Sumter

Daily Flag Raising

Mountain Howitzer

Major Thomas Anderson

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Inside Fort Sumter

Powder Magazine

Museum