HENRY FORD’S RAILROAD

HENRY FORD’S RAILROAD

Copyright © 2006, 2012 by Mark Strecker.

By 1920, American railroads had fallen onto hard times, or at least harder than usual. Throughout their entire history, few of them had made much money, and those that did often found their funds stolen by unscrupulous owners. When Henry Ford bought his own railroad in that year, he confronted not only a stubborn industry unwilling to change its ways, but also one crippled by government overregulation. To understand his struggle to make his road a success, one must first have some knowledge of the American railroad industry’s history.

The Great Northern Railway in Washington State

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

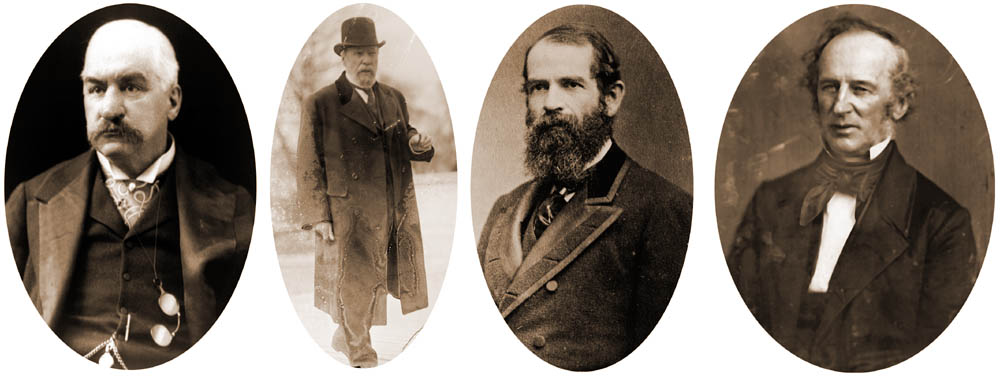

The Civil War transformed railroads into one of America’s biggest industries, helped along when President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill to make possible a transcontinental rail line, one that started with the Central Pacific Railroad and ended in California with the Union Pacific. After the war, four New York-based men—Jay Gould, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jim Fisk and Daniel Drew—decided to take control of the Eastern railroads. They became known as “robber barons” because of their greedy ambitions and unethical and often illegal business dealings. Jay Gould made a living buying small, failing railroads that he combined with others into larger, successful ones. He then sold them off for a profit. If one of his recently sold railroads went bust, he or one of his agents bought it back at a deflated price. In 1865, while attempting to acquire the Erie Railroad, he became acquainted with its president, Daniel Drew, and they hatched all sort of nefarious plots to make money off the Erie.

At the same time another New York businessman, “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt, decided he wanted to get into the railroad business as well. He bought the New York and Harlem Railroad, the Hudson River Railroad, then the New York Central Railroad, the last of which he merged with the Hudson. When he set his sights on the Erie Railroad, he came into conflict with Gould and Drew.

These two allied with financier Jim Fisk and fought Vanderbilt’s unwanted takeover attempt by printing and selling counterfeit Erie stock certificates. When Vanderbilt convinced a New York judge to have his three rivals arrested, they fled to Jersey City for safety. Tired of the fight, Vanderbilt contacted Drew and offered a settlement. If his three rivals would pay him a total of $4,550,000 in cash, stocks and bonds, he would abandon the matter and have the charges against them dropped. The three agreed. In 1872, the Erie went broke and Vanderbilt acquired it anyway. Drew declared bankruptcy, one of Fisk’s associates killed him, and Gould moved west to take control of the nearly bankrupt Union Pacific, which he revived. Vanderbilt continued to build his railroad empire until his death in January 1877, when his heirs took over.

A second generation of railroad men made the machinations of the first Robber Barons look tame. James Pierpont Morgan, the financer who also started United States Steel and helped to organize General Electric, either outright bought his own railroads or helped to facilitate the consolidation of them for his business associates. By 1906, these manipulations brought the control of two-thirds of all American railroads (150,000 track-miles out of 228,000) under six owners, although most lines still ran under their own names.

In 1895, two major railroads dominated Western America: the Northern Pacific Railway, owned by Morgan, and the Great Northern Railway, owned by James J. Hill. Hill thought if he and Morgan pooled their railroads together as one, they could stop competing with one another and instead focus on expanding control of the European and Asian goods crossing from the East to West Coasts. By connecting coastal ports, they could transport freight from one to the other at a low cost via their railroads, then sell it to outgoing merchant ships.

At the same time another New York businessman, “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt, decided he wanted to get into the railroad business as well. He bought the New York and Harlem Railroad, the Hudson River Railroad, then the New York Central Railroad, the last of which he merged with the Hudson. When he set his sights on the Erie Railroad, he came into conflict with Gould and Drew.

These two allied with financier Jim Fisk and fought Vanderbilt’s unwanted takeover attempt by printing and selling counterfeit Erie stock certificates. When Vanderbilt convinced a New York judge to have his three rivals arrested, they fled to Jersey City for safety. Tired of the fight, Vanderbilt contacted Drew and offered a settlement. If his three rivals would pay him a total of $4,550,000 in cash, stocks and bonds, he would abandon the matter and have the charges against them dropped. The three agreed. In 1872, the Erie went broke and Vanderbilt acquired it anyway. Drew declared bankruptcy, one of Fisk’s associates killed him, and Gould moved west to take control of the nearly bankrupt Union Pacific, which he revived. Vanderbilt continued to build his railroad empire until his death in January 1877, when his heirs took over.

A second generation of railroad men made the machinations of the first Robber Barons look tame. James Pierpont Morgan, the financer who also started United States Steel and helped to organize General Electric, either outright bought his own railroads or helped to facilitate the consolidation of them for his business associates. By 1906, these manipulations brought the control of two-thirds of all American railroads (150,000 track-miles out of 228,000) under six owners, although most lines still ran under their own names.

In 1895, two major railroads dominated Western America: the Northern Pacific Railway, owned by Morgan, and the Great Northern Railway, owned by James J. Hill. Hill thought if he and Morgan pooled their railroads together as one, they could stop competing with one another and instead focus on expanding control of the European and Asian goods crossing from the East to West Coasts. By connecting coastal ports, they could transport freight from one to the other at a low cost via their railroads, then sell it to outgoing merchant ships.

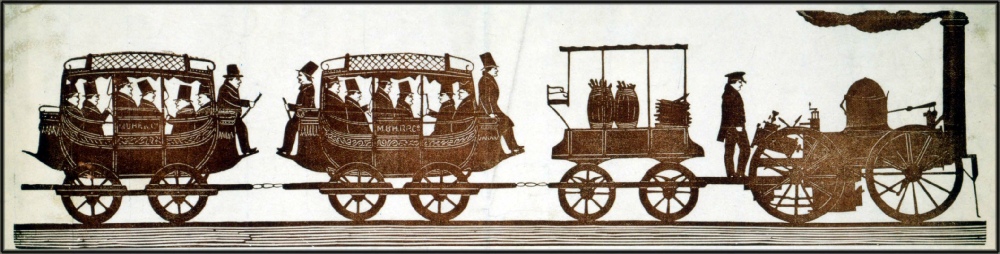

The First Steam Railroad Passenger Train in America

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Morgan liked the idea, so he and Hill agreed to the combination, but the Minnesota Supreme Court stopped their plan because it violated that state’s law forbidding parallel railroads from merging. Morgan and Hill circumvented this by taking advantage of a new type of corporation, the holding company, now offered in New Jersey. From that state they founded Northern Securities. Through means that would make even the best stockbroker’s head spin, this company effectively took control of both the Northern Pacific and Great Northern Railways.

Left to Right: John Pierpont Morgan, James Hill, Jay Gould, Cornelius Vanderbilt

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

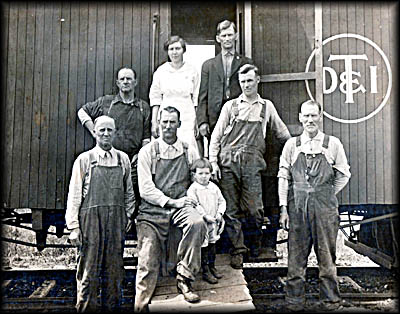

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Workers

Photo by Arnielee. Wikimedia Commons.

Photo by Arnielee. Wikimedia Commons.

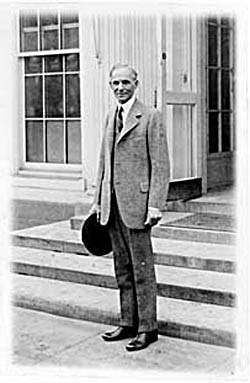

Henry Ford

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Ford Motor’s River Rouge Plant

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Interstate Commerce Commission.

Photo by Harris & Ewing.

Library of Congress

Photo by Harris & Ewing.

Library of Congress

Edsel Ford blaming the sale of the DT&I on interference at a Congressional hearing on January 8, 1938.

Photo by Harris & Ewing.

Library of Congress.

Photo by Harris & Ewing.

Library of Congress.

When Minnesota’s governor, Samuel R. Van Sant, caught wind of this, he started an action to stop it, but the president of Pacific Northern, with the express permission of Morgan, successfully bribed state officials to stop Van Sant’s effort. In February 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt, who often consulted Morgan on matters of finance, took things into his own hands. He ordered the prosecution of Northern Securities because it had violated the Sherman Act, a law making such unfair competition illegal. In 1904, the Supreme Court ordered Northern Securities to dissolve. Morgan could not understand what he had done wrong, which reflected the attitude of all the big railroad owners at the time.

Many did not like the way railroads handled freight rates, either. Large customers like Standard Oil received big discounts, often referred to as rebates. Railroads then bilked smaller customers, especially farmers and cattlemen, to make up the difference. Public officials who opposed the railroad often received lifetime free railroad passes if they would shut up, and most did. This form of bribe, not illegal at the time but certainly unethical, stopped most complaints.

Politicians more sympathetic to farmers than to getting free rides took action on behalf of their beleaguered constituents. One in particular, Senator Shelby Moore Cullom of Illinois, had worked as a farmer and rural schoolteacher reading and practicing law. He became the architect of a new government agency started specifically to deal with the problems railroads caused, the Interstate Commerce Commission. Established in 1887, Cullom wanted it to regulate railroads within reason; he never desired it to hamper their ability to do business or make a profit. Although it had some initial success, the ICC soon became impotent against railroad lawyers.

In 1903, it received its first enforcement powers with the passing of the Elkins Act. When railroads managed to find ways to circumvent this, Congress passed the Hepburn Act of 1906 to give the ICC even more authority. Now it could fix rates on its own and restrict the use of free passes. Each of the ICC’s powers came as a reactionary measure to something illegal or unethical the railroads had done rather than as a proactive measure, causing the agency to abuse its powers since it had no real goal or direction. In the end, it made the railroads almost incapable of producing a legal profit.

Its most insidious rule, one that plagued Henry Ford, came in the form of a profit cap. The ICC assigned a railroad a total value, then limited its profits to 5½ percent above that, although it could, at its discretion, raise this another one-half percent after two years from a railroad’s start date. If, for example, a railroad had the value of $100,000, it could make no more than $550,000 in profit. Anything above that went into the ICC’s own coffers. Half this surplus went to aiding railroads during economic slumps, and the other half for giving out loans to financially strapped roads.

The ICC caused the railroads so many problems that by 1917, when the United States entered World War I, the entire railway system of America had become a financial and logistical mess. In an effort to save money, most railroads had the policy of never moving empty cars. If a train went full from Point A to Point B to unload, it would stay at Point B until it had something to haul back to Point A. This hampered the movement of war materials and frustrated President Woodrow Wilson to the point where he nationalized the railroads, an order that lasted from January 1, 1918, to March 1, 1920.

Wilson’s son-in-law, William Gibbs McAdoo, an ex-railroad man and at the time the Secretary of Treasury, oversaw this new empire. McAdoo quickly got things well organized and caused trains to haul war materials quite efficiently. Unfortunately for the railroads, he also abused them. When the government returned control to the owners, they found their track systems run down and their equipment worn out. Railroad companies collectively filed for over $1 billion in damages, but the government only compensated them for about $48 million. Many simply could not recover.

On such road, the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton, had no way of complying with a government order to replace its trestle over the River Rouge with a lift bridge. The bridge would cost $350,000, but the company had a debt of about $1.8 million. When the DT&I’s directors realized the government order had occurred because Ford Motor Company needed large boats to sail unhindered down the river to Ford’s River Rouge factory, they asked Henry Ford if he would buy some bonds to pay for its cost.

Ford took a closer look at this ailing railroad and discovered some interesting things about it. It ran near his River Rouge factory. It extended south into the bottom of Ohio, very close to coalmines he had recently purchased in Kentucky and West Virginia. It also went to the Ohio River. If Ford Motor shipped cars to the Ohio River via a railroad, it could put them on barges that would in turn take them to the Mississippi River and south toward New Orleans. Best of all, the DT&I crossed virtually all major east-west railroads in the country, giving Ford Motor an opportunity to transfer Model Ts to these other railroads and get them to their destinations at a lower cost than ever before. With all these advantages in mind, he decided to buy the DT&I Railroad in 1920. Ford Motor itself did not purchase it because under the law of the time an industrial manufacturer could not own stock in a railroad.

Many did not like the way railroads handled freight rates, either. Large customers like Standard Oil received big discounts, often referred to as rebates. Railroads then bilked smaller customers, especially farmers and cattlemen, to make up the difference. Public officials who opposed the railroad often received lifetime free railroad passes if they would shut up, and most did. This form of bribe, not illegal at the time but certainly unethical, stopped most complaints.

Politicians more sympathetic to farmers than to getting free rides took action on behalf of their beleaguered constituents. One in particular, Senator Shelby Moore Cullom of Illinois, had worked as a farmer and rural schoolteacher reading and practicing law. He became the architect of a new government agency started specifically to deal with the problems railroads caused, the Interstate Commerce Commission. Established in 1887, Cullom wanted it to regulate railroads within reason; he never desired it to hamper their ability to do business or make a profit. Although it had some initial success, the ICC soon became impotent against railroad lawyers.

In 1903, it received its first enforcement powers with the passing of the Elkins Act. When railroads managed to find ways to circumvent this, Congress passed the Hepburn Act of 1906 to give the ICC even more authority. Now it could fix rates on its own and restrict the use of free passes. Each of the ICC’s powers came as a reactionary measure to something illegal or unethical the railroads had done rather than as a proactive measure, causing the agency to abuse its powers since it had no real goal or direction. In the end, it made the railroads almost incapable of producing a legal profit.

Its most insidious rule, one that plagued Henry Ford, came in the form of a profit cap. The ICC assigned a railroad a total value, then limited its profits to 5½ percent above that, although it could, at its discretion, raise this another one-half percent after two years from a railroad’s start date. If, for example, a railroad had the value of $100,000, it could make no more than $550,000 in profit. Anything above that went into the ICC’s own coffers. Half this surplus went to aiding railroads during economic slumps, and the other half for giving out loans to financially strapped roads.

The ICC caused the railroads so many problems that by 1917, when the United States entered World War I, the entire railway system of America had become a financial and logistical mess. In an effort to save money, most railroads had the policy of never moving empty cars. If a train went full from Point A to Point B to unload, it would stay at Point B until it had something to haul back to Point A. This hampered the movement of war materials and frustrated President Woodrow Wilson to the point where he nationalized the railroads, an order that lasted from January 1, 1918, to March 1, 1920.

Wilson’s son-in-law, William Gibbs McAdoo, an ex-railroad man and at the time the Secretary of Treasury, oversaw this new empire. McAdoo quickly got things well organized and caused trains to haul war materials quite efficiently. Unfortunately for the railroads, he also abused them. When the government returned control to the owners, they found their track systems run down and their equipment worn out. Railroad companies collectively filed for over $1 billion in damages, but the government only compensated them for about $48 million. Many simply could not recover.

On such road, the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton, had no way of complying with a government order to replace its trestle over the River Rouge with a lift bridge. The bridge would cost $350,000, but the company had a debt of about $1.8 million. When the DT&I’s directors realized the government order had occurred because Ford Motor Company needed large boats to sail unhindered down the river to Ford’s River Rouge factory, they asked Henry Ford if he would buy some bonds to pay for its cost.

Ford took a closer look at this ailing railroad and discovered some interesting things about it. It ran near his River Rouge factory. It extended south into the bottom of Ohio, very close to coalmines he had recently purchased in Kentucky and West Virginia. It also went to the Ohio River. If Ford Motor shipped cars to the Ohio River via a railroad, it could put them on barges that would in turn take them to the Mississippi River and south toward New Orleans. Best of all, the DT&I crossed virtually all major east-west railroads in the country, giving Ford Motor an opportunity to transfer Model Ts to these other railroads and get them to their destinations at a lower cost than ever before. With all these advantages in mind, he decided to buy the DT&I Railroad in 1920. Ford Motor itself did not purchase it because under the law of the time an industrial manufacturer could not own stock in a railroad.

He purchased the DT&I for $5 million, although the road had a value between $16 and $20 million. All the old stockholders sold out save for two men from New York, Leon Tannenbaum and Benjamin Strauss. They figured if Henry Ford became involved with the DT&I, it would make money, so they intended to reap the dividends right alongside the car mogul himself. This greatly irked Ford, especially when the two periodically filed court actions to ensure that they did not miss out on a single dividend.

Throughout its history, the DT&I had spent much of its time in receivership, often ending up consolidated with other railroad lines. It had changed its name five times, this not counting those when it did so after merging with another road. Thanks to the government’s abuse of it during World War I, its system had fallen in a ruin. According to Ford R. Bryan’s Beyond the Model T: The Other Ventures of Henry Ford (Revised Edition), Ford found that he “had bought 456 miles of badly deteriorated railroad meandering through Ohio [with] 41 small railroad stations, 75 old steam locomotives, 2,800 mortgaged freight cars, and 27 vintage passenger cars.” Upon having his new line surveyed, he learned that it suffered from 400 illegal encroachments, which included unwanted shacks and areas where other railroads outright used DT&I tracks. Ford had his lawyers deal with them. He decided to invest between $10 and $15 million into his new road for renovations.

The DT&I possessed 2,700 employees, many of whom the line did not need, so he let fifty-one percent of them go, although by 1926 he had 2,895 essential employees on the payroll. Only fifty-three of the DT&I’s locomotives ran, and of those all but two engines needed repairing or a complete overhaul. The DT&I’s back shop (as railroads call their repair shops) did not have the modern equipment to complete this task, so Ford had a new one built at his River Rogue factory complex.

When he became the DT&I’s president on March 4, 1921, he immediately fired the entire board of directors and replaced them with his own people. He ridded the company of all its lawyers and streamlined its accounting department. He initiated a program to boost worker morale. As he had long ago learned, happy employees work more productively. Either personally or at his direction, he started investigating ways to improve the DT&I’s overall efficiency.

In November 1921, William Atherton DuPuy interviewed Henry about railroads and published this in a railroad journal under the title “If I Ran the Railroads.” In it Ford outlined his vision for improving his own railroad and suggestions as to what other railroads could do to improve themselves. Not only would he try most of these ideas, many of them worked quite successfully. For example, when train cars (called rolling stock by railroads) went around curves, their axels could not give, so one side of the wheels slipped considerably. His design engineers solved this problem by inventing a divided axel that also weighed less. Realizing that much of the wear and tear that the track system (called a physical plant) occurred because trains often ran overloaded, he suggested their cars ought to weigh and carry less to reduce this problem.

At this time railroads treated their employees rather poorly. Many railroaders had to work long shifts and unwanted overtime. A hierarchal system of rank prevailed that put conductors on the top and the switchman at the bottom. Ford ignored all this. He abolished the company’s union outright (no laws existed at this time to prevent him from doing so), decreed all workers would make a minimum of $6 a day for eight hours, and no one would work overtime. Trains would not run on Sundays unless they carried livestock or perishable goods. He decided to pay engineers and conductors the same, giving them both about $100 more a month than anyone else in the industry. Employees could buy company stock as part of a profit-sharing scheme, although the ICC gave him trouble over this. The DT&I implemented a new policy stating no one lost his job unless he had tried and failed at all available positions. During the slow times of the year, workers switched positions to avoid layoffs, something no other railroad did.

Of course Ford expected much from his employees. He allowed no idleness and insisted on absolute cleanliness. Except for flagmen, employees cleaned when they had nothing else to do. They had to have fresh clothes, a close shave, and wear a pair of goggles and a cap—management suggested white but this did not work well with dirty steam engines. Employees absolutely could not smoke, drink or gamble while on the job. Everyone also received a brass identification badge. Employees could receive free medical attention and acquire coal at cost. Ford had all his locomotives plated with nickel to give them a look of cleanliness. Engineers and other employees then had the task of keeping them spotless. In an age when even new steam engines looked old because of the soot from burning coal, this innovation prompting other railroads to follow suit.

As the employee work standard improved, the DT&I launched a major campaign to upgrade its track to a heavier gauge, add gravel where needed, and replace old ties. Always looking for ways to reduce wear, Henry decided that steep grades and hairpin curves in the track system needed to go. One area in particular, a run in Michigan from Malinta to Petersburg, had so many curves and steep grades that Henry decided to build a new bypass line that would go from Napoleon to Wauseon. Called the Malinta Cutoff, it reduced the number of curves from forty-one to two and route mileage from 76.21 to 55.71, which decreased travel time by thirty-five percent.

Ford also wanted a direct connection from the Rogue to the DT&I. For legal reasons, he created a corporation in July 1920 called the Detroit and Ironton Company to build and own the new 13.5 miles of track, which it would lease to the DT&I. He wanted to start the project in 1920, but the ICC hampered his efforts, forcing him to wait two years before work began. Tired of such interference, he created another corporation, the Ford Transportation Company, to buy new freight cars that he could lease to the DT&I to avoid the red tape of buying them directly.

Throughout its history, the DT&I had spent much of its time in receivership, often ending up consolidated with other railroad lines. It had changed its name five times, this not counting those when it did so after merging with another road. Thanks to the government’s abuse of it during World War I, its system had fallen in a ruin. According to Ford R. Bryan’s Beyond the Model T: The Other Ventures of Henry Ford (Revised Edition), Ford found that he “had bought 456 miles of badly deteriorated railroad meandering through Ohio [with] 41 small railroad stations, 75 old steam locomotives, 2,800 mortgaged freight cars, and 27 vintage passenger cars.” Upon having his new line surveyed, he learned that it suffered from 400 illegal encroachments, which included unwanted shacks and areas where other railroads outright used DT&I tracks. Ford had his lawyers deal with them. He decided to invest between $10 and $15 million into his new road for renovations.

The DT&I possessed 2,700 employees, many of whom the line did not need, so he let fifty-one percent of them go, although by 1926 he had 2,895 essential employees on the payroll. Only fifty-three of the DT&I’s locomotives ran, and of those all but two engines needed repairing or a complete overhaul. The DT&I’s back shop (as railroads call their repair shops) did not have the modern equipment to complete this task, so Ford had a new one built at his River Rogue factory complex.

When he became the DT&I’s president on March 4, 1921, he immediately fired the entire board of directors and replaced them with his own people. He ridded the company of all its lawyers and streamlined its accounting department. He initiated a program to boost worker morale. As he had long ago learned, happy employees work more productively. Either personally or at his direction, he started investigating ways to improve the DT&I’s overall efficiency.

In November 1921, William Atherton DuPuy interviewed Henry about railroads and published this in a railroad journal under the title “If I Ran the Railroads.” In it Ford outlined his vision for improving his own railroad and suggestions as to what other railroads could do to improve themselves. Not only would he try most of these ideas, many of them worked quite successfully. For example, when train cars (called rolling stock by railroads) went around curves, their axels could not give, so one side of the wheels slipped considerably. His design engineers solved this problem by inventing a divided axel that also weighed less. Realizing that much of the wear and tear that the track system (called a physical plant) occurred because trains often ran overloaded, he suggested their cars ought to weigh and carry less to reduce this problem.

At this time railroads treated their employees rather poorly. Many railroaders had to work long shifts and unwanted overtime. A hierarchal system of rank prevailed that put conductors on the top and the switchman at the bottom. Ford ignored all this. He abolished the company’s union outright (no laws existed at this time to prevent him from doing so), decreed all workers would make a minimum of $6 a day for eight hours, and no one would work overtime. Trains would not run on Sundays unless they carried livestock or perishable goods. He decided to pay engineers and conductors the same, giving them both about $100 more a month than anyone else in the industry. Employees could buy company stock as part of a profit-sharing scheme, although the ICC gave him trouble over this. The DT&I implemented a new policy stating no one lost his job unless he had tried and failed at all available positions. During the slow times of the year, workers switched positions to avoid layoffs, something no other railroad did.

Of course Ford expected much from his employees. He allowed no idleness and insisted on absolute cleanliness. Except for flagmen, employees cleaned when they had nothing else to do. They had to have fresh clothes, a close shave, and wear a pair of goggles and a cap—management suggested white but this did not work well with dirty steam engines. Employees absolutely could not smoke, drink or gamble while on the job. Everyone also received a brass identification badge. Employees could receive free medical attention and acquire coal at cost. Ford had all his locomotives plated with nickel to give them a look of cleanliness. Engineers and other employees then had the task of keeping them spotless. In an age when even new steam engines looked old because of the soot from burning coal, this innovation prompting other railroads to follow suit.

As the employee work standard improved, the DT&I launched a major campaign to upgrade its track to a heavier gauge, add gravel where needed, and replace old ties. Always looking for ways to reduce wear, Henry decided that steep grades and hairpin curves in the track system needed to go. One area in particular, a run in Michigan from Malinta to Petersburg, had so many curves and steep grades that Henry decided to build a new bypass line that would go from Napoleon to Wauseon. Called the Malinta Cutoff, it reduced the number of curves from forty-one to two and route mileage from 76.21 to 55.71, which decreased travel time by thirty-five percent.

Ford also wanted a direct connection from the Rogue to the DT&I. For legal reasons, he created a corporation in July 1920 called the Detroit and Ironton Company to build and own the new 13.5 miles of track, which it would lease to the DT&I. He wanted to start the project in 1920, but the ICC hampered his efforts, forcing him to wait two years before work began. Tired of such interference, he created another corporation, the Ford Transportation Company, to buy new freight cars that he could lease to the DT&I to avoid the red tape of buying them directly.

With a practical diesel-electric locomotive still years away, he sought to find a way to eliminate the mechanically complicated, inefficient and costly steam locomotive. One remedy involved the electrification of a portion of the line between the Rouge plant and Flat Rock, Michigan. Short electrified lines already existed when the DT&I Railroad News announced the plan in July 1923. Its seventeen miles of track qualified as one of the longest anywhere in America at the time. The Rouge powerhouse would provide the electricity.

Electric engines had many advantages over steam. Mechanically uncomplicated, they needed little maintenance and could run for long periods without requiring any sort of overhaul. The flip of a switch turned them on, and they ran twice as efficiently as steam engines. Henry had two electric locomotives built. The electrical components came from Westinghouse, the traction motors (the electric motors attached to each wheel) from Highland Park (another of Ford’s Detroit plants), and the box shell from the River Rouge factory. The engines drew power from overhead wires. The power lines carried alternating current because direct current could not travel long distances and would necessitate the use of electrical substations.

Yet AC presented a problem: no traction engine in 1923 existed that could use it. To remedy this situation, Ford engineers created a DC power generator that used the AC current as its power source. This generator converted its AC power to DC and sent that to the traction motors. The DT&I’s two electric locomotives each generated up to 5,000 horsepower and could reach a maximum speed of 17 miles per hour. They averaged 3,800 horsepower. By 1927, they ran 24 hours a day, six days a week.

The electrification project, while progressive, never extended beyond its initial run. Plans existed to expand it south, but for unknown reasons the ICC put a stop to it. The Rouge also had trouble meeting the power demands. After Henry sold the DT&I in 1929, its new owners did a study on the cost of running an electric line versus a steam one, concluded that latter cost less, and switched it back to steam.

Ford also worked to improve his railroad’s money-losing passenger service, which had the reliability of a Roulette wheel and needed most of its equipment replaced. Given a choice, he would have discontinued it altogether because he only wanted the DT&I to haul coal and Model Ts, not people. However, the ICC dictated that all railroads run a passenger service, so he had no choice in the matter.

DT&I passenger trains faced frequent delays such as waiting for late passengers and stopping to allow freight trains to pass because the latter had priority over the former when it came to track usage. Henry ordered passenger trains to take precedence over freight. He had the entire passenger service schedule revised and rearranged for greater efficiency, rebuild all cars, and implemented a policy to keep them clean—so spotless, in fact, that people gathered to watch DT&I passenger trains pass by because of their uniqueness. The DT&I had no sleeping or Pullman cars and kept the overall number down to reduce weight. To lower costs even further, Ford schemed to eliminate the need for a locomotive. He had two gas-electric self-propelled lightweight passenger train cars constructed for testing. Not only did the cars not work that well, Ford’s son Edsel wrecked one while trying it out. Ford stopped the project after that.

Within a short time, Ford did what no other owner of the DT&I had ever managed: he made it run well and produce a good profit. By the end of his ownership, he reported that the line had made a total of $36 million. Because Ford Motor accounted for 70 percent of DT&I’s freight capacity, the road lost money in only one year, 1927, when the Rouge shut down to retool for the Model A. Still, the DT&I did pick up additional non-Ford work. In a four year period, its number of customers increased from 150 to over 500 in the Toledo area alone.

So why did Ford sell his railroad? He became disgusted with the strict and weird regulations of the ICC. Right from the beginning of his ownership it caused him problems. It had considerably undervalued the DT&I. Ford’s lawyers estimated its value at $23,061,208, but the ICC gave it one of $11,826,300. Since it could not make a profit of more than 5½ percent above that, Ford found much of his road’s surplus revenue going into ICC coffers. The ICC refused to let him use new lightweight train cars. It also forbade him from making freight rate deals because the Robber Barons had once done this for Standard Oil and other large companies. The ICC kept delaying his acquisition of the Toledo-Detroit Railroad, which he wanted to give him access to Toledo without having to pay to use other railroads’ tracks. When it fined him $20,000 for violating the Elkins Act, he decided he had had enough.

In 1929, Edsel approach Pennroad Corporation, a new holding company created by the Pennsylvania Railroad, to ask if it would like to buy his father’s railroad. After a bit of wheeling and dealing, the company paid Henry $36 million for it at the end of June 1929. Four months later the stock market collapsed. Any chance that Pennroad, and perhaps the rest of the railroad industry, would follow Henry’s innovative lead in how to run a railroad crashed with it.

In the grip of the Depression, Pennroad undid all that Ford had changed. It reinstated seniority, the labor union returned, wages dropped to match other railroads, and Ford’s strict maintenance standards went the way of the Dodo. According to Scott D. Trostel’s Detroit, Toledo and Ironton Railroad: Henry Ford’s Railroad, the DT&I’s “gross revenues fell by $4 million” in 1930. The next year it ran at a revenue level half of what it had in 1929.🕜

Electric engines had many advantages over steam. Mechanically uncomplicated, they needed little maintenance and could run for long periods without requiring any sort of overhaul. The flip of a switch turned them on, and they ran twice as efficiently as steam engines. Henry had two electric locomotives built. The electrical components came from Westinghouse, the traction motors (the electric motors attached to each wheel) from Highland Park (another of Ford’s Detroit plants), and the box shell from the River Rouge factory. The engines drew power from overhead wires. The power lines carried alternating current because direct current could not travel long distances and would necessitate the use of electrical substations.

Yet AC presented a problem: no traction engine in 1923 existed that could use it. To remedy this situation, Ford engineers created a DC power generator that used the AC current as its power source. This generator converted its AC power to DC and sent that to the traction motors. The DT&I’s two electric locomotives each generated up to 5,000 horsepower and could reach a maximum speed of 17 miles per hour. They averaged 3,800 horsepower. By 1927, they ran 24 hours a day, six days a week.

The electrification project, while progressive, never extended beyond its initial run. Plans existed to expand it south, but for unknown reasons the ICC put a stop to it. The Rouge also had trouble meeting the power demands. After Henry sold the DT&I in 1929, its new owners did a study on the cost of running an electric line versus a steam one, concluded that latter cost less, and switched it back to steam.

Ford also worked to improve his railroad’s money-losing passenger service, which had the reliability of a Roulette wheel and needed most of its equipment replaced. Given a choice, he would have discontinued it altogether because he only wanted the DT&I to haul coal and Model Ts, not people. However, the ICC dictated that all railroads run a passenger service, so he had no choice in the matter.

DT&I passenger trains faced frequent delays such as waiting for late passengers and stopping to allow freight trains to pass because the latter had priority over the former when it came to track usage. Henry ordered passenger trains to take precedence over freight. He had the entire passenger service schedule revised and rearranged for greater efficiency, rebuild all cars, and implemented a policy to keep them clean—so spotless, in fact, that people gathered to watch DT&I passenger trains pass by because of their uniqueness. The DT&I had no sleeping or Pullman cars and kept the overall number down to reduce weight. To lower costs even further, Ford schemed to eliminate the need for a locomotive. He had two gas-electric self-propelled lightweight passenger train cars constructed for testing. Not only did the cars not work that well, Ford’s son Edsel wrecked one while trying it out. Ford stopped the project after that.

Within a short time, Ford did what no other owner of the DT&I had ever managed: he made it run well and produce a good profit. By the end of his ownership, he reported that the line had made a total of $36 million. Because Ford Motor accounted for 70 percent of DT&I’s freight capacity, the road lost money in only one year, 1927, when the Rouge shut down to retool for the Model A. Still, the DT&I did pick up additional non-Ford work. In a four year period, its number of customers increased from 150 to over 500 in the Toledo area alone.

So why did Ford sell his railroad? He became disgusted with the strict and weird regulations of the ICC. Right from the beginning of his ownership it caused him problems. It had considerably undervalued the DT&I. Ford’s lawyers estimated its value at $23,061,208, but the ICC gave it one of $11,826,300. Since it could not make a profit of more than 5½ percent above that, Ford found much of his road’s surplus revenue going into ICC coffers. The ICC refused to let him use new lightweight train cars. It also forbade him from making freight rate deals because the Robber Barons had once done this for Standard Oil and other large companies. The ICC kept delaying his acquisition of the Toledo-Detroit Railroad, which he wanted to give him access to Toledo without having to pay to use other railroads’ tracks. When it fined him $20,000 for violating the Elkins Act, he decided he had had enough.

In 1929, Edsel approach Pennroad Corporation, a new holding company created by the Pennsylvania Railroad, to ask if it would like to buy his father’s railroad. After a bit of wheeling and dealing, the company paid Henry $36 million for it at the end of June 1929. Four months later the stock market collapsed. Any chance that Pennroad, and perhaps the rest of the railroad industry, would follow Henry’s innovative lead in how to run a railroad crashed with it.

In the grip of the Depression, Pennroad undid all that Ford had changed. It reinstated seniority, the labor union returned, wages dropped to match other railroads, and Ford’s strict maintenance standards went the way of the Dodo. According to Scott D. Trostel’s Detroit, Toledo and Ironton Railroad: Henry Ford’s Railroad, the DT&I’s “gross revenues fell by $4 million” in 1930. The next year it ran at a revenue level half of what it had in 1929.🕜