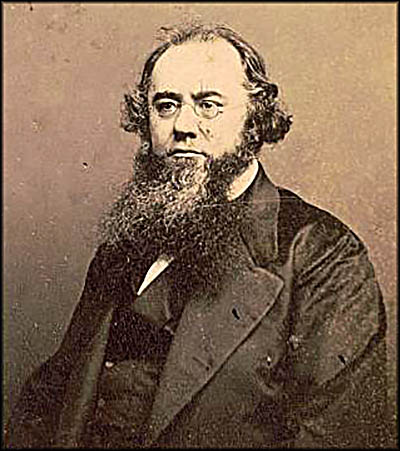

Upon becoming president, one of Lincoln’s staunchest allies and friends was his secretary of war, Edwin McMasters Stanton. Born in Steubenville on December 19, 1814, he became a prominent lawyer and, for a time, had a partnership with George Wythe McCook, one of the Fighting McCooks, in the city. In 1849 Stanton became famous nationally by winning Pennsylvania v. Wheeling & Belmont Bridge Co. in the Supreme Court. When the state of Virginia contracted the Belmont Bridge Company to construct a suspension bridge over the Ohio River for use by the railroad, the state of Pennsylvania, represented by Stanton, sued the construction company because its bridge was too low to allow large steamboats to pass under.

Stanton, a Democrat, opposed slavery, a view he formed while at Kenyon College. President James Buchanan appointed Stanton as his attorney general, and from this office he urged the president to preserve the union even if it meant military force. Buchanan declined, but Stanton’s advice hadn’t gone unnoticed by Lincoln. He made Stanton his secretary of war. Despite being good friends with General George B. McClellan, Stanton was one of the members of the cabinet who recommended this officer’s removal when it became clear he was unsuited to be head of the Union Army. From that point on McClellan considered Stanton an enemy. During his tenure in office, Stanton joined the Republican Party. An effective and honest secretary of war, he became Lincoln’s friend and was greatly upset by his assassination.

Stanton kept his cabinet position under President Andrew Johnson. For a time they worked together, but Stanton’s growing opposition to Johnson’s policies led the president to ask for Stanton’s resignation. When Stanton refused, Johnson fired him. This was just what Congress, filled with Radical Republicans, had wanted. On March 2, 1867, it had passed the Tenure of Office Act making it illegal for the president to fire certain government officials confirmed by Congress, and this included cabinet members. After Congress reinstated Stanton, Johnson tried to appoint another man the secretary of war, so Congress retaliated with impeachment, the first time this had happened to a president.

When the Senate failed to remove Johnson from office by one vote (likely because someone bribed Senator Edmund G. Ross to vote for acquittal), Stanton resigned. By now his poor health and finances had taken a toll on him. He did manage to rouse himself to campaign for Ulysses S. Grant for president, who rewarded him with an appointment to the Supreme Court. But before he could take the seat, he died on December 24, 1869.🕜

Stanton, a Democrat, opposed slavery, a view he formed while at Kenyon College. President James Buchanan appointed Stanton as his attorney general, and from this office he urged the president to preserve the union even if it meant military force. Buchanan declined, but Stanton’s advice hadn’t gone unnoticed by Lincoln. He made Stanton his secretary of war. Despite being good friends with General George B. McClellan, Stanton was one of the members of the cabinet who recommended this officer’s removal when it became clear he was unsuited to be head of the Union Army. From that point on McClellan considered Stanton an enemy. During his tenure in office, Stanton joined the Republican Party. An effective and honest secretary of war, he became Lincoln’s friend and was greatly upset by his assassination.

Stanton kept his cabinet position under President Andrew Johnson. For a time they worked together, but Stanton’s growing opposition to Johnson’s policies led the president to ask for Stanton’s resignation. When Stanton refused, Johnson fired him. This was just what Congress, filled with Radical Republicans, had wanted. On March 2, 1867, it had passed the Tenure of Office Act making it illegal for the president to fire certain government officials confirmed by Congress, and this included cabinet members. After Congress reinstated Stanton, Johnson tried to appoint another man the secretary of war, so Congress retaliated with impeachment, the first time this had happened to a president.

When the Senate failed to remove Johnson from office by one vote (likely because someone bribed Senator Edmund G. Ross to vote for acquittal), Stanton resigned. By now his poor health and finances had taken a toll on him. He did manage to rouse himself to campaign for Ulysses S. Grant for president, who rewarded him with an appointment to the Supreme Court. But before he could take the seat, he died on December 24, 1869.🕜

She was probably based on Agustina de Aragón, the Maid of Zaragoza, who fired a cannon while defending that Spanish city from the 1808–1809 French siege of it during the Peninsular War. She was immortalized in Lord Byron’s 1812 poem “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.” Jeremiah Zeamer, who proposed this idea, found the earliest published account mentioning Molly Pitcher was an 1840 article by George W.P. Custis that appeared in the National Intelligencer. The earliest newspaper account I found was an 1839 one in Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania’s Columbia Democrat. She also appeared in two 1834 sources, both of which reported her name was Mary Picture, a well known fortune teller known as “Moll” or “Molly” Pitcher. This woman died at the age of seventy-five in 1813.

The Battle of Monmouth did nothing to sully Steuben’s reputation since the men had retreated at the order of an officer, not because of their own panic. After the war Steuben expected but never received a pension or other compensation for his inflated list of expenses. A spendthrift with no head for money management, in a short time he went from living on a lavish rented Manhattan estate called the Louvre to becoming a destitute tenant in a Wall Street boarding house. At the end of 1788 his debt had grown so high that his old comrades Hamilton and Walker took control of his money. Upon becoming secretary of the treasury in May 1890, Hamilton was finally able to secure Steuben a pension of $2,500 a year. Steuben never again lived the rich life he so loved, but he did retire alongside Walker in a log cabin near Utica, New York. It was here he died on November 28, 1794. He never visited the fort or town named after him.

Many famous people passed through or came from Steubenville. In August 1803, Meriwether Lewis departed with his newly constructed boats from Pittsburgh with the goal of reaching Louisville, Kentucky, to pick up his partner, William Clark. During this month the Ohio River is usually low and this year was no exception. One of the boats got stuck on a sandbar by Steubenville. Some from the expedition came into town and hired oxen to pull their vessel from its captive shoal.

In 1861 Abraham Lincoln, whose train was taking him to Washington, D.C. where he’d assume the office of president, stopped in Steubenville for half an hour. One newspaper reported that a cheering crowd of about 8,000 to 10,000 people lined both banks of the Ohio to see his train pass. The people of Steubenville had built a platform for him at the end of Market Street near Colonel Musgrove’s hotel from which he could speak, but when the train stopped at 2:30 that afternoon, Lincoln didn’t use it. Instead he stood on a plank stuck out of the rear car. A light rain caused umbrellas to go up, obscuring the view for those at the back. Before Lincoln could speak, an Irishman insisted on shaking his hand, sheepishly admitting that he’d voted for Stephen Douglas. Lincoln spoke briefly, beginning with “I fear that the great confidence placed in my ability is unfounded; indeed, I am sure of it. Encompassed by vast difficulties as I am, nothing shall be wanting on my part, if sustained by the American people and God.”

The Battle of Monmouth did nothing to sully Steuben’s reputation since the men had retreated at the order of an officer, not because of their own panic. After the war Steuben expected but never received a pension or other compensation for his inflated list of expenses. A spendthrift with no head for money management, in a short time he went from living on a lavish rented Manhattan estate called the Louvre to becoming a destitute tenant in a Wall Street boarding house. At the end of 1788 his debt had grown so high that his old comrades Hamilton and Walker took control of his money. Upon becoming secretary of the treasury in May 1890, Hamilton was finally able to secure Steuben a pension of $2,500 a year. Steuben never again lived the rich life he so loved, but he did retire alongside Walker in a log cabin near Utica, New York. It was here he died on November 28, 1794. He never visited the fort or town named after him.

Many famous people passed through or came from Steubenville. In August 1803, Meriwether Lewis departed with his newly constructed boats from Pittsburgh with the goal of reaching Louisville, Kentucky, to pick up his partner, William Clark. During this month the Ohio River is usually low and this year was no exception. One of the boats got stuck on a sandbar by Steubenville. Some from the expedition came into town and hired oxen to pull their vessel from its captive shoal.

In 1861 Abraham Lincoln, whose train was taking him to Washington, D.C. where he’d assume the office of president, stopped in Steubenville for half an hour. One newspaper reported that a cheering crowd of about 8,000 to 10,000 people lined both banks of the Ohio to see his train pass. The people of Steubenville had built a platform for him at the end of Market Street near Colonel Musgrove’s hotel from which he could speak, but when the train stopped at 2:30 that afternoon, Lincoln didn’t use it. Instead he stood on a plank stuck out of the rear car. A light rain caused umbrellas to go up, obscuring the view for those at the back. Before Lincoln could speak, an Irishman insisted on shaking his hand, sheepishly admitting that he’d voted for Stephen Douglas. Lincoln spoke briefly, beginning with “I fear that the great confidence placed in my ability is unfounded; indeed, I am sure of it. Encompassed by vast difficulties as I am, nothing shall be wanting on my part, if sustained by the American people and God.”

In mid-August they met again. Because Congress had told its representatives in France to stop sending over foreigners wanting to become generals in its army, Franklin still refused to commit any funds for Steuben’s journey. Two of Steuben’s friends, Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais and Claude-Louise de St. Germain, arranged for Steuben to go American as a volunteer with no promise of a commission. Beaumarchais loaned Steuben the money to pay for the journey.

To increase the chances that Congress would give him a commission, Steuben’s credentials were invented. He went from a nobody to being promoted to a former lieutenant-general in the Prussian Army who had severed the Prussian king for twenty years and participated in numerous military campaigns. For good measure they claimed Steuben firmly believed in the cause for American independence, which he could have cared less about. Deane, Franklin, St. Germaine, and Dean’s secretary, Louis de L’Estarjette, wrote letters to members of Congress promoting these fabrications.

Steuben sailed for America in September 1777 and arrived at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on the first of December. He made his way to York, Pennsylvania, where Congress had relocated after the British occupied Philadelphia. Here he met with some of its members. Impressed, they sent him to Valley Forge to serve under the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, George Washington.

Although people in power soon realized they’d been bamboozled when it came to Steuben’s credentials, Washington saw his potential and made him his inspector general. Steuben knew his business. Despite speaking virtually no English, which he learned over the next year, he decided to personally train the troops, a plan approved by Washington. Speaking French, he had his aid, Pierre-Etienne du Ponceau, do much of the translating. He also employed the services of Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens.

It’s a wonder Steuben didn’t just walk away in disgust. Here before him was no professional army. Most enlisted men lacked uniforms, many didn’t have working guns, and their officers had no idea how to readily locate those under their command. There was no uniform code of drilling, either, leaving each colonel to issue commands as he saw fit. Realizing that the men needed respond to a given command the same way no matter who their officer was, Steuben set about writing a drill manual, the first one day the U.S. Army ever used. Copies were made in longhand for lack of a printing press.

Steuben decided to train a core of 100 men to create a model company who would then instruct the others. Unfortunately for him, du Ponceau’s vocabulary didn’t include military jargon, so Steuben sometimes resorted to pantomime. He taught each soldier to march on a one by one basis. When he became frustrated with their progress, he either let loose the only swear word in English he knew—“Goddamn!”—or he had another aid, Captain Benjamin Walker, translate his explicative-laden French for him. Despite this harshness, his men loved him, in part because he was known to invite enlisted ones to his lavish dinners.

During his trek from York to Valley Forge, he had stopped at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he became acquainted with American officer William York. Soon enough the youthful York showed up in Valley Forge and took up residence with his new friend. Rumors sprouted up that they were lovers, but Washington ignored them. Walker also moved into Steuben’s quarters. Although there is not a piece of historical evidence that one can consider a smoking gun, it is likely Steuben was gay and just as probable that no one cared because he was such a good officer.

To increase the chances that Congress would give him a commission, Steuben’s credentials were invented. He went from a nobody to being promoted to a former lieutenant-general in the Prussian Army who had severed the Prussian king for twenty years and participated in numerous military campaigns. For good measure they claimed Steuben firmly believed in the cause for American independence, which he could have cared less about. Deane, Franklin, St. Germaine, and Dean’s secretary, Louis de L’Estarjette, wrote letters to members of Congress promoting these fabrications.

Steuben sailed for America in September 1777 and arrived at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on the first of December. He made his way to York, Pennsylvania, where Congress had relocated after the British occupied Philadelphia. Here he met with some of its members. Impressed, they sent him to Valley Forge to serve under the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, George Washington.

Although people in power soon realized they’d been bamboozled when it came to Steuben’s credentials, Washington saw his potential and made him his inspector general. Steuben knew his business. Despite speaking virtually no English, which he learned over the next year, he decided to personally train the troops, a plan approved by Washington. Speaking French, he had his aid, Pierre-Etienne du Ponceau, do much of the translating. He also employed the services of Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens.

It’s a wonder Steuben didn’t just walk away in disgust. Here before him was no professional army. Most enlisted men lacked uniforms, many didn’t have working guns, and their officers had no idea how to readily locate those under their command. There was no uniform code of drilling, either, leaving each colonel to issue commands as he saw fit. Realizing that the men needed respond to a given command the same way no matter who their officer was, Steuben set about writing a drill manual, the first one day the U.S. Army ever used. Copies were made in longhand for lack of a printing press.

Steuben decided to train a core of 100 men to create a model company who would then instruct the others. Unfortunately for him, du Ponceau’s vocabulary didn’t include military jargon, so Steuben sometimes resorted to pantomime. He taught each soldier to march on a one by one basis. When he became frustrated with their progress, he either let loose the only swear word in English he knew—“Goddamn!”—or he had another aid, Captain Benjamin Walker, translate his explicative-laden French for him. Despite this harshness, his men loved him, in part because he was known to invite enlisted ones to his lavish dinners.

During his trek from York to Valley Forge, he had stopped at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he became acquainted with American officer William York. Soon enough the youthful York showed up in Valley Forge and took up residence with his new friend. Rumors sprouted up that they were lovers, but Washington ignored them. Walker also moved into Steuben’s quarters. Although there is not a piece of historical evidence that one can consider a smoking gun, it is likely Steuben was gay and just as probable that no one cared because he was such a good officer.

Upon learning of this, an enraged Logan gathered up a small war party and attacked white settlers on the western side of the Monongahela River, killing around thirteen, a number that included children. This gave Lord Dunmore the excuse he needed to outright attack Cayuga and Shawnee towns in the land he wanted to claim for his colony, so he sent a force of 2,000 to do so. Logan allied himself with Hokolesqua and went to war. The brief conflict that followed became known as known as Lord Dunmore’s War. In October the Shawnees came to Camp Charlotte and signed a treaty that ceded their land to Virginia. Though dubious in nature considering it was signed under duress, it nonetheless stood.

The Cayugas surrendered separately at Chillicothe. Although he didn’t attend it personally, Logan did send the message that has since become known as “Logan’s Lament” in which he mistakenly accused Cresap of killing members of his family.

The Cayugas surrendered separately at Chillicothe. Although he didn’t attend it personally, Logan did send the message that has since become known as “Logan’s Lament” in which he mistakenly accused Cresap of killing members of his family.

In 1772 the British abandoned Fort Pitt, leaving whites who had illegally settled the region unprotected. In the minds of the ambitious governors of Pennsylvania and Virginia, it also meant a lack of a royal claim, leaving them to annex the region for their own colonies. To that end both sent an agent to facilitate their claims. Arthur St. Clair represented Pennsylvania and Doctor John Connolly represented Virginia. The two settled in Pittsburgh and neither recognized the other’s claims.

The biggest trouble was that while it was true the Iroquois Confederation had ceded this land to the British by signing the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, it wasn’t theirs to give away. It belonged to the Shawnee, and they threatened to kill any surveyors caught on it. This they had done in May of the previous year to a surveying party from Virginia, leaving only one man alive to tell the colonial governor, John Murray, Lord Dunmore, to keep his colonists out of Shawnee lands.

On the pretext of peace, a prominent trader named George Croghan invited several Shawnee chiefs to parley at Point Pleasant in what is now West Virginia. Among those who came were Hokolesqua (Cornstalk) and his son, Elinipsico. A trap, Croghan took them hostage. Whites attacked them upon their release, killing Hokolesqua’s son. The Shawnee retaliated, prompting Connelly to write a circular letter warning whites that the native people of the region planned to attack them. The idea was to stir up trouble, which it did.

Michael Cresap was one of those who read the letter. Born in Maryland on June 20, 1742, for several years Cresap ran a store there, but in the Spring of 1772 financial troubles prompted him to move to the Ohio River near modern Wheeling, West Virginia, where he began building houses for settlers. This despite the fact that the Proclamation of 1763 forbade British subjects from settling any territory west of the Appalachians. Looking for vengeance, Cresap gathered up and led a party of settlers operating about ninety miles down the river from Pittsburgh. On April 27 the party scalped two Shawnees paddling a canoe on the Ohio River, quickly following this up by killing another and wounding two more.

Four days later and fifty miles up the river near Yellow Creek in what is now Columbiana County’s Yellow Creek Township, a war party of whites led by Daniel Greathouse, who knew Cresap, decided to enact its own retribution. Joshua Baker invited a Cayuga party consisting of two men and two women to a shooting match at his cabin. Hidden outside were Greathouse and his men, who swooped in and killed them, then murdered another two who arrived later. When six more came to investigate what had happened to their friends, they too were attacked. Two died and one was wounded. Among those butchered that day were Logan’s mother, brother and pregnant sister.

The biggest trouble was that while it was true the Iroquois Confederation had ceded this land to the British by signing the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, it wasn’t theirs to give away. It belonged to the Shawnee, and they threatened to kill any surveyors caught on it. This they had done in May of the previous year to a surveying party from Virginia, leaving only one man alive to tell the colonial governor, John Murray, Lord Dunmore, to keep his colonists out of Shawnee lands.

On the pretext of peace, a prominent trader named George Croghan invited several Shawnee chiefs to parley at Point Pleasant in what is now West Virginia. Among those who came were Hokolesqua (Cornstalk) and his son, Elinipsico. A trap, Croghan took them hostage. Whites attacked them upon their release, killing Hokolesqua’s son. The Shawnee retaliated, prompting Connelly to write a circular letter warning whites that the native people of the region planned to attack them. The idea was to stir up trouble, which it did.

Michael Cresap was one of those who read the letter. Born in Maryland on June 20, 1742, for several years Cresap ran a store there, but in the Spring of 1772 financial troubles prompted him to move to the Ohio River near modern Wheeling, West Virginia, where he began building houses for settlers. This despite the fact that the Proclamation of 1763 forbade British subjects from settling any territory west of the Appalachians. Looking for vengeance, Cresap gathered up and led a party of settlers operating about ninety miles down the river from Pittsburgh. On April 27 the party scalped two Shawnees paddling a canoe on the Ohio River, quickly following this up by killing another and wounding two more.

Four days later and fifty miles up the river near Yellow Creek in what is now Columbiana County’s Yellow Creek Township, a war party of whites led by Daniel Greathouse, who knew Cresap, decided to enact its own retribution. Joshua Baker invited a Cayuga party consisting of two men and two women to a shooting match at his cabin. Hidden outside were Greathouse and his men, who swooped in and killed them, then murdered another two who arrived later. When six more came to investigate what had happened to their friends, they too were attacked. Two died and one was wounded. Among those butchered that day were Logan’s mother, brother and pregnant sister.

About Native American resistance to white encroachment on this land, Historic Fort Steuben reproduces two speeches, one by a Cayuga war chief named Soyechtowa or Tocaniadorogon—whose English name was James Logan—and the other from Chief Seattle (or Seathl). The first man lived in the area and figures heavily in the history that led up to Fort Steuben’s construction. The latter lived on the West Coast in what is now the city of Seattle. He believed in peaceful coexistence with the whites. His inclusion in the museum is a bit baffling considering he neither fits into the timeframe its covers nor lived anywhere near Ohio. So I’ll just ignore him and suggest the museum find a better example of an accommodating Native American.

Logan made a famous speech known as “Logan’s Lament” that appeared in Thomas Jefferson’s influential book Notes on the State of Virginia. Logan was born in 1725 in the Pennsylvania village of Shamokin (modern Sunbury). He was son of an Oneida chief, Shikellamy, and a Cayuga woman. Because of his mother’s lineage, Logan was considered a Cayuga, one of the founding tribes of the Iroquois Confederation. The Cayugas were from New York’s Finger Lakes Region and lived mostly along Lake Cayuga.

Chief Shikellamy worked as an intermediary between the Pennsylvania colonial government and the Iroquois Confederacy, leading him to befriend the colonial secretary James Logan, his son’s namesake. In 1774 Logan moved his family along at the mouth of the Yellow Creek with a community of breakaway Cayugas who had no connection with the Iroquois Grand Council which became known as the Mingo. For most of his life Logan was a friend to the whites and bore them no ill will.

Logan made a famous speech known as “Logan’s Lament” that appeared in Thomas Jefferson’s influential book Notes on the State of Virginia. Logan was born in 1725 in the Pennsylvania village of Shamokin (modern Sunbury). He was son of an Oneida chief, Shikellamy, and a Cayuga woman. Because of his mother’s lineage, Logan was considered a Cayuga, one of the founding tribes of the Iroquois Confederation. The Cayugas were from New York’s Finger Lakes Region and lived mostly along Lake Cayuga.

Chief Shikellamy worked as an intermediary between the Pennsylvania colonial government and the Iroquois Confederacy, leading him to befriend the colonial secretary James Logan, his son’s namesake. In 1774 Logan moved his family along at the mouth of the Yellow Creek with a community of breakaway Cayugas who had no connection with the Iroquois Grand Council which became known as the Mingo. For most of his life Logan was a friend to the whites and bore them no ill will.

Historic Fort Steuben

Historic Fort Steuben

Inside the Museum

Logan Finding His Murdered Family

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

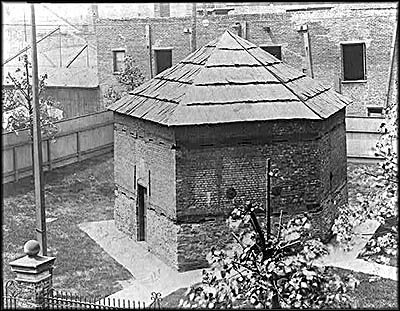

When Britain signed a peace treaty with the newly recognized United States after the latter’s successful revolution, it gave up a generous parcel of land west of the thirteen states known as the Northwest Territory. From this the states Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin were carved. At the time, the United States was governed by the Articles of Confederation, a document that created a weak federal system lacking the power to tax. Desperate to raise revenue to pay off the nation’s debts, Congress decided to sell the Northwest Territory off in parcels. For it to be successful they first needed to rid the area of white squatters and Native Americans, the latter having possessed the land for thousands of years and who were disinclined to give it up.

Blockhouse at Fort Pitt about 1902.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

I appeal to any white man to say, if ever he entered Logan's cabin hungry, and he gave him not meat; if ever he came cold and naked, and he clothed him not. During the course of the last long and bloody war, Logan remained idle in his cabin, an advocate for peace. Such was my love for the whites, that my countrymen pointed as they passed, and said, Logan is the friend of white men. I had even thought to have lived with you, but for the injuries of one man. Col. Cresap, the last spring, in cold blood, and unprovoked, murdered all the relations of Logan, not sparing even my women and children. There runs not a drop of my blood in the veins of any living creature. This called on me for revenge. I have sought it: I have killed many: I have fully glutted my vengeance. For my country, I rejoice at the beams of peace. But do not harbour [sic] a thought that mine is the joy of fear. Logan never felt fear. He will not turn on his heel to save his life. Who is there to mourn for Logan? Not one.

Logan continued to fight during the Revolution. In 1780 he was killed in or near Detroit, likely as a result of quarrel with a nephew. Cresap was initially vilified as a monster for “killing” members of Logan’s family (even though he had nothing to do with it), but when the Revolution broke out, his reputation was quickly restored. He raised a militia rifle company over which he became captain. Dressed as Native Americans, it marched to New England. The trek took a toll on Cresap’s health, forcing him to depart for New York City to recuperate. He died there on October 18, 1775. You can find his grave in Manhattan at Trinity Graveyard, the final resting place of many prominent figures from American history such as Alexander Hamilton, Jacob John Astor, and Robert Fulton.

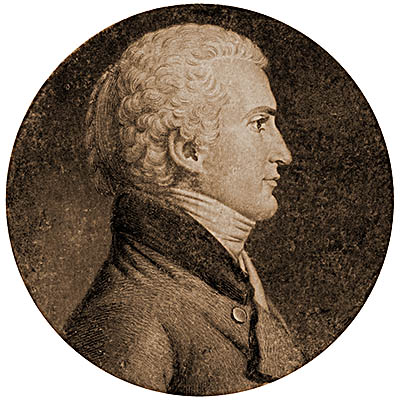

The fort at Steubenville, whose history is detailed in my new book the Hidden History of Northeast Ohio, was named for Friedrich Wilhelm Augustus von Steuben, the Prussian officer who during the terrible winter at Valley Forge shaped General George Washington’s men into a professional army. Now here was a colorful character if ever history produced one. Born in Magdeburg, Germany, on September 17, 1730, he was the son of Wilhelm Augustin von Steuben and Maria Justina Dorothea von Jagow. His father was an engineer in the Prussian Army and was for much of his son’s early years stationed in Russia. In 1742 the family took root in Breslau, Silesia, where young Friedrich learned mathematics from the Jesuits. In 1746 he joined the Prussian Army as a lance corporal. Three years later he received a commission as an ensign and, in 1752, became a second lieutenant.

The Seven Years’ War (the European name for the French and Indian War) broke out in 1856. Steuben served in the infantry and as a staff officer during it. Taken prison by the Russians in 1861, he was confined in St. Petersburg where, as an officer and a fluent speaker of Russian, he was given a great deal of freedom. While here he befriended Karl Peter Ulrich, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, heir to the Russian throne. Upon ascending to throne in 1862, Ulrich, now Tsar Peter III, decided to sue for peace despite the fact Russia was winning the war. Steuben wrote to the Prussian foreign minister to report that the tsar not only offered to end hostilities, it would give Prussia back its territory lost in the fighting. (Not surprising, Russia aristocracy didn’t like this a bit, so the Prussian-born Peter only served as Tsar for six months before being removed.) Steuben became the assistant to the man Prussia’s king Frederick II sent as an emissary to St. Petersburg to undertake negotiations, which went very well. With Russia out of the conflict, Prussia had more resources to deal with its other enemies.

When Steuben returned home in May 1862, King Frederick personally received him. Having lost many officers in the war, the king decided to establish a school to instruct staff officers and gave Steuben a place there. He was soon thrown out after crossing a powerful classmate, then mustered out of the army when the king downsized it. Steuben found work in the court of Hohenzollern-Hechingen, a small principality in the Black Forest in southwestern Germany where he served as Prince Josef Friedrich Wilhelm’s chief minister. In 1769 the margrave of Baden bestowed upon Steuben a knighthood in the Order of Fidelity based on a fake lineage created by Steuben’s father. Steuben then promoted himself to baron, the first of many falsehoods he would perpetrate during his career. Historian Thomas Fleming labeled him “the magnificent fraud.”

In 1777 the bankruptcy of Hohenzollern-Hechingen forced Steuben to go looking for work elsewhere. The margrave of Baden offered him a place in his army. Before he could take it, the offer was derailed by an accusation out of Hechingen accusing him of having improper knowledge of small boys. Desperate for work and always in debt, he made his way to France looking for a place in its army. Here he was introduced to American diplomats Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane. Their first meeting on June 25, 1777, did not go well. While Deane seemed keen on employing Steuben, Franklin refused to offer money for a trip to America or promise him a commission in the Continental Army once there.

The fort at Steubenville, whose history is detailed in my new book the Hidden History of Northeast Ohio, was named for Friedrich Wilhelm Augustus von Steuben, the Prussian officer who during the terrible winter at Valley Forge shaped General George Washington’s men into a professional army. Now here was a colorful character if ever history produced one. Born in Magdeburg, Germany, on September 17, 1730, he was the son of Wilhelm Augustin von Steuben and Maria Justina Dorothea von Jagow. His father was an engineer in the Prussian Army and was for much of his son’s early years stationed in Russia. In 1742 the family took root in Breslau, Silesia, where young Friedrich learned mathematics from the Jesuits. In 1746 he joined the Prussian Army as a lance corporal. Three years later he received a commission as an ensign and, in 1752, became a second lieutenant.

The Seven Years’ War (the European name for the French and Indian War) broke out in 1856. Steuben served in the infantry and as a staff officer during it. Taken prison by the Russians in 1861, he was confined in St. Petersburg where, as an officer and a fluent speaker of Russian, he was given a great deal of freedom. While here he befriended Karl Peter Ulrich, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, heir to the Russian throne. Upon ascending to throne in 1862, Ulrich, now Tsar Peter III, decided to sue for peace despite the fact Russia was winning the war. Steuben wrote to the Prussian foreign minister to report that the tsar not only offered to end hostilities, it would give Prussia back its territory lost in the fighting. (Not surprising, Russia aristocracy didn’t like this a bit, so the Prussian-born Peter only served as Tsar for six months before being removed.) Steuben became the assistant to the man Prussia’s king Frederick II sent as an emissary to St. Petersburg to undertake negotiations, which went very well. With Russia out of the conflict, Prussia had more resources to deal with its other enemies.

When Steuben returned home in May 1862, King Frederick personally received him. Having lost many officers in the war, the king decided to establish a school to instruct staff officers and gave Steuben a place there. He was soon thrown out after crossing a powerful classmate, then mustered out of the army when the king downsized it. Steuben found work in the court of Hohenzollern-Hechingen, a small principality in the Black Forest in southwestern Germany where he served as Prince Josef Friedrich Wilhelm’s chief minister. In 1769 the margrave of Baden bestowed upon Steuben a knighthood in the Order of Fidelity based on a fake lineage created by Steuben’s father. Steuben then promoted himself to baron, the first of many falsehoods he would perpetrate during his career. Historian Thomas Fleming labeled him “the magnificent fraud.”

In 1777 the bankruptcy of Hohenzollern-Hechingen forced Steuben to go looking for work elsewhere. The margrave of Baden offered him a place in his army. Before he could take it, the offer was derailed by an accusation out of Hechingen accusing him of having improper knowledge of small boys. Desperate for work and always in debt, he made his way to France looking for a place in its army. Here he was introduced to American diplomats Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane. Their first meeting on June 25, 1777, did not go well. While Deane seemed keen on employing Steuben, Franklin refused to offer money for a trip to America or promise him a commission in the Continental Army once there.

His training trickled down to those not initially part of the first 100 and by spring the Americans had been shaped in a professional force instead of a ragtag band of militiamen with little discipline. Their first test came at the Battle of Monmouth in New Jersey on July 28, 1778. Ten days earlier the British had abandoned Philadelphia, so Washington aimed to attack the stretched out British army at Monmouth Court House. On an exceptionally hot day, Major General Charles Lee was sent to harass the British until Washington could bring up the main force from Valley Forge.

The unexpected arrival of British reinforcements so spooked Lee that he ordered a retreat. Worse, he delayed informing Washington about this. When the latter arrived, he found Lee’s force in disarray. Fortunately the new discipline instilled by Steuben allowed Washington to easily reverse Lee’s mess and stop a British advance. Technically the British won this engagement, but the Americans didn’t break and run as they often had before. Lee was court martialed and dismissed from the army.

During the battle the high temperature caused men to collapse from heat exhaustion. A legend says an artillery man stricken by heatstroke was replaced by his wife, Molly Pitcher, who had been ferrying water to thirsty men. With a name like Molly Pitcher even the dimmest historian knows this was not her real name, and over the years several candidates have been proposed. One was Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley, who died in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in January 1832 at the age of eighty-nine. Washington supposedly made her a lieutenant colonel with half pay for life. Even had he wanted to, only Congress had this power, and it did no such thing for any woman during the Revolution.

The fact that Molly Pitcher never existed is something acknowledged by historians at least as early as 1909. Yet as late as 2008, Encyclopedia Britannica treated her as an historical person, though it’s since corrected this error. She also continues to appear in American history schoolbooks. Despite the overwhelming consensus among historians that Molly Pitcher is a mythic figure, people still persist on perpetrating it. One 2019 article I came across purported that Washington made her a warrant officer, a bit of a demotion from being a lieutenant colonel.

The unexpected arrival of British reinforcements so spooked Lee that he ordered a retreat. Worse, he delayed informing Washington about this. When the latter arrived, he found Lee’s force in disarray. Fortunately the new discipline instilled by Steuben allowed Washington to easily reverse Lee’s mess and stop a British advance. Technically the British won this engagement, but the Americans didn’t break and run as they often had before. Lee was court martialed and dismissed from the army.

During the battle the high temperature caused men to collapse from heat exhaustion. A legend says an artillery man stricken by heatstroke was replaced by his wife, Molly Pitcher, who had been ferrying water to thirsty men. With a name like Molly Pitcher even the dimmest historian knows this was not her real name, and over the years several candidates have been proposed. One was Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley, who died in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in January 1832 at the age of eighty-nine. Washington supposedly made her a lieutenant colonel with half pay for life. Even had he wanted to, only Congress had this power, and it did no such thing for any woman during the Revolution.

The fact that Molly Pitcher never existed is something acknowledged by historians at least as early as 1909. Yet as late as 2008, Encyclopedia Britannica treated her as an historical person, though it’s since corrected this error. She also continues to appear in American history schoolbooks. Despite the overwhelming consensus among historians that Molly Pitcher is a mythic figure, people still persist on perpetrating it. One 2019 article I came across purported that Washington made her a warrant officer, a bit of a demotion from being a lieutenant colonel.

The mythical Molly Pitcher.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Alexander Hamilton as painted

by Thomas Hamilton Crawford

Library of Congress

by Thomas Hamilton Crawford

Library of Congress

Meriwether Lewis

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Edwin Stanton

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Barracks

Canoe

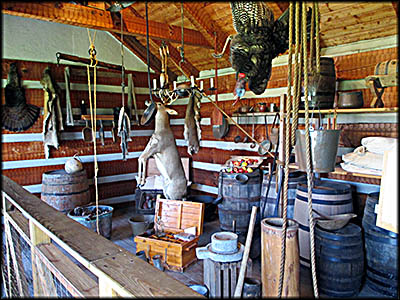

Commissary

Hospital

Medical Instruments

Officer's Quarters

Barracks

Friedrich Wilhelm Augustus von Steuben

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

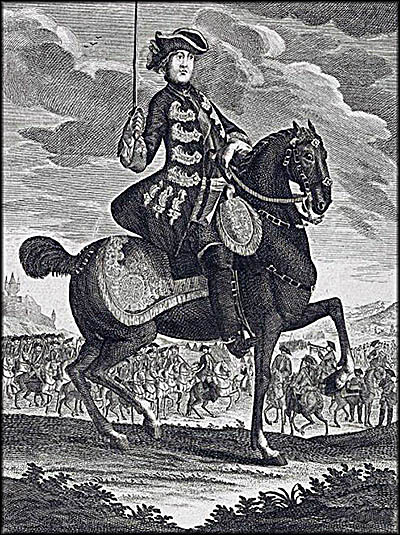

Frederick II (the Great) of Prussia

Benjamin Franklin at the French Court

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

General Washington and Lafayette Inspecting Troops at Valley Forge

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Major General Charles Lee

Library of Congress

Library of Congress