Historical Society of Old Brooklyn Museum

Entrance

Interior

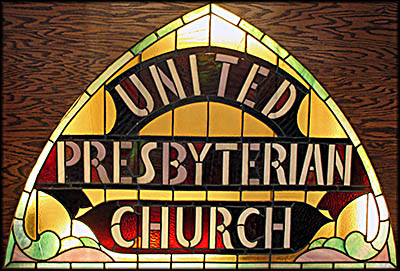

As the neighborhood changed, this church's congregation shrunk and it closed.

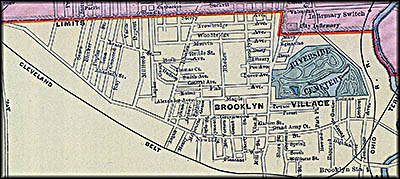

Brooklyn Village 1903

David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

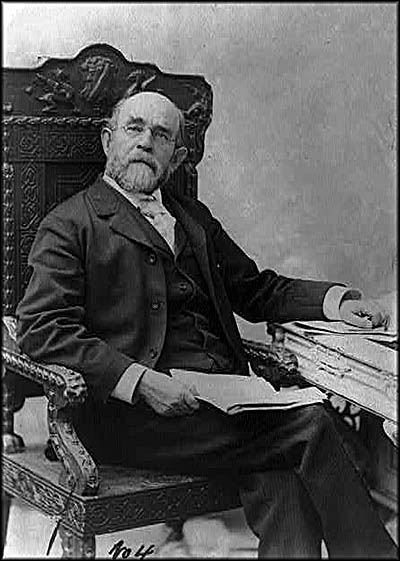

Tom Johnson

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

The Historical Society of Old Brooklyn Museum tells the story of one of Cleveland’s many neighborhoods. Like all of them in this fine city, Old Brooklyn has its own unique history and character. I must admit that when I entered the museum, a wave of dismay overcame me because it’s about the size of a living room, albeit one stuffed full with historic artifacts, photos and newspaper articles taken from the Brooklyn News covering the walls. The most colorful artifact here is a stained glass window from the former United Presbyterian Church that closed in 2016 because the neighborhood’s demographic changes had severely reduced the size of its congregation.

Visitors are welcome to go through the Society’s many filing cabinets. These are packed with historical documents, newspaper articles, and other written materials which tell the story of Old Brooklyn. I spent quite some time going through these as well as reading some of the books the historical society has. Even better, the Society’s president, Constance Ewazen, was there that day, and she shared some of her unrivaled knowledge of the neighborhood’s history and geography with me.

If you’ve ever visited the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo, you’ve been in Old Brooklyn, whose borders span east to west from the Cuyahoga River to the Brooklyn (no relation to the neighborhood), and south to north from Parma to Brookside Park. The current neighborhood traces its origin back to the village of Brighton. Carved out of land from a farm that belonged Warren Young, its first attempt at becoming an incorporated municipality was short-lived. In 1836 Samuel H. Barstow secured the village’s incorporation and the next year its mayorship. Less than a year later, its citizens decided to allow the village charter to expire. In 1889 it reincorporated as South Brooklyn. In 1903, a real estate book, Picturesque South Brooklyn Village by Thomas A. Knight, advertised South Brooklyn as an excellent place to live, but it only wanted “the better class of citizens.” These days the neighbor is a potpourri of difference ethnicities and classes.

The village of South Brooklyn ceased to be on December 11, 1905, when the Cleveland City Council voted to annex it. This was a mutual decision, the village council having voted in favor of it on December 2, 1903. From this deal South Brooklyn gained many benefits, including Cleveland taking responsibility for its infrastructure and all financial liabilities. In return Cleveland got the village’s power plant, increasing the city’s allover capacity, which in turn reduced the cost of electricity for powering lights and streetcars.

If you’ve ever visited the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo, you’ve been in Old Brooklyn, whose borders span east to west from the Cuyahoga River to the Brooklyn (no relation to the neighborhood), and south to north from Parma to Brookside Park. The current neighborhood traces its origin back to the village of Brighton. Carved out of land from a farm that belonged Warren Young, its first attempt at becoming an incorporated municipality was short-lived. In 1836 Samuel H. Barstow secured the village’s incorporation and the next year its mayorship. Less than a year later, its citizens decided to allow the village charter to expire. In 1889 it reincorporated as South Brooklyn. In 1903, a real estate book, Picturesque South Brooklyn Village by Thomas A. Knight, advertised South Brooklyn as an excellent place to live, but it only wanted “the better class of citizens.” These days the neighbor is a potpourri of difference ethnicities and classes.

The village of South Brooklyn ceased to be on December 11, 1905, when the Cleveland City Council voted to annex it. This was a mutual decision, the village council having voted in favor of it on December 2, 1903. From this deal South Brooklyn gained many benefits, including Cleveland taking responsibility for its infrastructure and all financial liabilities. In return Cleveland got the village’s power plant, increasing the city’s allover capacity, which in turn reduced the cost of electricity for powering lights and streetcars.

Henry George

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

This decommissioned RTA train car at the Northern Ohio Railway Museum is part of the system that traces it origins to the one started by Mayor Tom Johnson.

From this deal South Brooklyn gained many benefits, including Cleveland taking responsibility for its infrastructure and all financial liabilities. In return Cleveland got the village’s power plant, increasing the city’s allover capacity, which in turn reduced the cost of electricity for powering lights and streetcars.

The deal was part of Mayor Tom Loft Johnson’s strategy to fulfill his 1901 Progressive mayoral promise to lower streetcar fares to three cents. Based on his early life, one would have expected Johnson to become one of the late nineteenth century’s robber barons. He was born on a farm in Kentucky on July 18, 1854, one complete with slaves owned by his father, Albert William, who later served as a colonel in the Confederate Army. Ruined by the Civil War, the family moved to Louisville, and it was here that fifteen-year-old Tom got into the streetcar business as an office worker for a line owned by Antoine Bidermann, Jr. and Alfred Irénée du Pont.

Johnson invented and patented a coin box for the streetcars, and for this he was promoted to superintendent of the line. In 1876 he bought his first streetcar line in Indianapolis, Indiana, and three years later another in Cleveland. It was in this city that he, his wife Margaret, and two children settled. Johnson made much of his money buying up streetcar companies, consolidating them into a single line, then selling its stock at a price higher than what the new line was actually worth. After his relocation to Cleveland, he got into politics, serving as a Democratic congressman from 1891 to 1895, though his time in office didn’t slow down his business interests.

In 1895 he became president of the Detroit Citizen’s Street Railway Company in Michigan. Detroit’s reform mayor Hazen Pingree went to battle with Detroit Citizen’s by insisting it lower its fares from five to three cents. The fight taught Johnson something important. Advocating for lower streetcar fares was popular. By this point his attitude towards social justice had in any case changed considerably than when he was just starting off in busines. His change of heart is said to have occurred in 1883 when he read Henry George’s book Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth: The Remedy, which laid bare capitalism’s inequalities and made suggestions for reforming it.

Johnson declared his retirement from business as well as his lack of interest in returning to politics in January 1901. The next month a delegation of fifty Democrats visited him at his house and showed him a petition with around 15,000 signatures asking him to run for mayor. He acquiesced and ran on the platform of forcing Cleveland’s two streetcar lines to lower their fares from five to three cents. The two companies had consolidated in 1903 as the Cleveland Electric Railway Company, creating a monopoly.

Johnson wanted to the city to build its own line, but Ohio law forbade this. So he decided to work to bring a new line into the city as competition. This venture, the Municipal Traction Company, incorporated in 1906. Two years later it leased Cleveland Electric’s lines and ran them with a three cent fair. Later in the year financial and labor issues forced both companies into receivership. A federal judge, Robert W. Tayler, created a new franchise called Cleveland Railway Company that would operate at cost and be overseen by the city’s traction commissioners. This venture began on March 3, 1910, and lasted until its takeover by city-owned Cleveland Transit System on April 28, 1942.

The deal was part of Mayor Tom Loft Johnson’s strategy to fulfill his 1901 Progressive mayoral promise to lower streetcar fares to three cents. Based on his early life, one would have expected Johnson to become one of the late nineteenth century’s robber barons. He was born on a farm in Kentucky on July 18, 1854, one complete with slaves owned by his father, Albert William, who later served as a colonel in the Confederate Army. Ruined by the Civil War, the family moved to Louisville, and it was here that fifteen-year-old Tom got into the streetcar business as an office worker for a line owned by Antoine Bidermann, Jr. and Alfred Irénée du Pont.

Johnson invented and patented a coin box for the streetcars, and for this he was promoted to superintendent of the line. In 1876 he bought his first streetcar line in Indianapolis, Indiana, and three years later another in Cleveland. It was in this city that he, his wife Margaret, and two children settled. Johnson made much of his money buying up streetcar companies, consolidating them into a single line, then selling its stock at a price higher than what the new line was actually worth. After his relocation to Cleveland, he got into politics, serving as a Democratic congressman from 1891 to 1895, though his time in office didn’t slow down his business interests.

In 1895 he became president of the Detroit Citizen’s Street Railway Company in Michigan. Detroit’s reform mayor Hazen Pingree went to battle with Detroit Citizen’s by insisting it lower its fares from five to three cents. The fight taught Johnson something important. Advocating for lower streetcar fares was popular. By this point his attitude towards social justice had in any case changed considerably than when he was just starting off in busines. His change of heart is said to have occurred in 1883 when he read Henry George’s book Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth: The Remedy, which laid bare capitalism’s inequalities and made suggestions for reforming it.

Johnson declared his retirement from business as well as his lack of interest in returning to politics in January 1901. The next month a delegation of fifty Democrats visited him at his house and showed him a petition with around 15,000 signatures asking him to run for mayor. He acquiesced and ran on the platform of forcing Cleveland’s two streetcar lines to lower their fares from five to three cents. The two companies had consolidated in 1903 as the Cleveland Electric Railway Company, creating a monopoly.

Johnson wanted to the city to build its own line, but Ohio law forbade this. So he decided to work to bring a new line into the city as competition. This venture, the Municipal Traction Company, incorporated in 1906. Two years later it leased Cleveland Electric’s lines and ran them with a three cent fair. Later in the year financial and labor issues forced both companies into receivership. A federal judge, Robert W. Tayler, created a new franchise called Cleveland Railway Company that would operate at cost and be overseen by the city’s traction commissioners. This venture began on March 3, 1910, and lasted until its takeover by city-owned Cleveland Transit System on April 28, 1942.

All this took a personal toll on Johnson himself. He entered office at the age of forty-seven wealthy and healthy, and left frail and broke. It should be noted that during his time as mayor he did other things Progressives such as himself were known for. He had prisoners put into sunlit towers inside of dark cells, built public baths for the poor, and removed “Keep Off the Grass” signs from the city’s public parks.

In 1887 the establishment of Gustave Ruetenik & Sons sparked the growth of greenhouses in the neighborhood, making it known as the “Greenhouse Capital of the United States.” They grew seasonal vegetables such as lettuce and tomatoes to make them available year round. During clement weather some greenhouses planted sweet corn and cabbage outside. Around 1960 the price of natural gas for heating spiked, forcing many to close. Those that survived switched to selling flowers, trees, shrubs, and a miscellany of other plants.

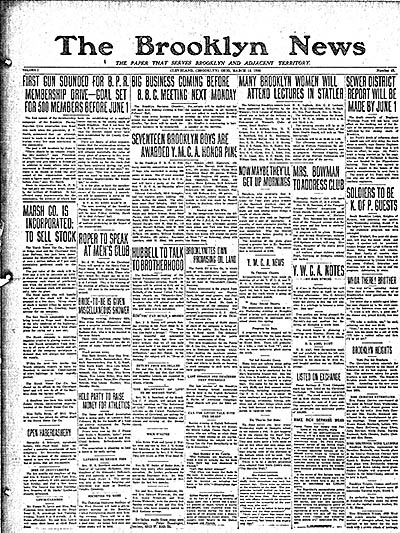

Even after its annexation, South Brooklyn in many ways kept its independence. It had, for example, the Brooklyn News, which focused almost exclusively on the neighborhood and was more like a bulletin board than a newspaper. The issues from the 1920s that I looked at were all four pages in length and don’t make for compelling reading. Headlines such as “Birthday Party at Krather Home” and “Church to Have Revival Services” were typical. One article, “Marsh Officials and Employees Have Good Time,” was about a 1919 Christmas dance that the Marsh Motor Company hosted in Glenn Hall.

Sometimes the paper did touch on topics of the day. An article in one issue the April 2, 1920, edition reported that at the quarterly meeting of Cuyahoga County’s Women’s Christian Temperance Union—one of the groups that bullied the government into establishing Prohibition—a fellow named E.P. Wiles spoke. He claimed that in Cleveland alone there were 100,000 people who couldn’t speak English and those who didn’t know this language were surely easy prey for Bolshevism. Why the English language would inoculate them from this he failed to say, probably because what he spouted was utter nonsense. But his speech was typical in 1920 because the United States had come under the spell of its first major Red Scare. People believed the Bolsheviks were going to infiltrate America and confiscate everyone’s property. Never mind that Russia was in the midst of a vicious civil war and had too many of its own problems to threaten anyone.

Another interesting event that occurred in the Old Brooklyn Neighborhood is the brutal robbery and murder of Wilfred C. Sly and George J. Fanner and December 31, 1920. More about this can be found in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the chapter about Cuyahoga County.🕜

In 1887 the establishment of Gustave Ruetenik & Sons sparked the growth of greenhouses in the neighborhood, making it known as the “Greenhouse Capital of the United States.” They grew seasonal vegetables such as lettuce and tomatoes to make them available year round. During clement weather some greenhouses planted sweet corn and cabbage outside. Around 1960 the price of natural gas for heating spiked, forcing many to close. Those that survived switched to selling flowers, trees, shrubs, and a miscellany of other plants.

Even after its annexation, South Brooklyn in many ways kept its independence. It had, for example, the Brooklyn News, which focused almost exclusively on the neighborhood and was more like a bulletin board than a newspaper. The issues from the 1920s that I looked at were all four pages in length and don’t make for compelling reading. Headlines such as “Birthday Party at Krather Home” and “Church to Have Revival Services” were typical. One article, “Marsh Officials and Employees Have Good Time,” was about a 1919 Christmas dance that the Marsh Motor Company hosted in Glenn Hall.

Sometimes the paper did touch on topics of the day. An article in one issue the April 2, 1920, edition reported that at the quarterly meeting of Cuyahoga County’s Women’s Christian Temperance Union—one of the groups that bullied the government into establishing Prohibition—a fellow named E.P. Wiles spoke. He claimed that in Cleveland alone there were 100,000 people who couldn’t speak English and those who didn’t know this language were surely easy prey for Bolshevism. Why the English language would inoculate them from this he failed to say, probably because what he spouted was utter nonsense. But his speech was typical in 1920 because the United States had come under the spell of its first major Red Scare. People believed the Bolsheviks were going to infiltrate America and confiscate everyone’s property. Never mind that Russia was in the midst of a vicious civil war and had too many of its own problems to threaten anyone.

Another interesting event that occurred in the Old Brooklyn Neighborhood is the brutal robbery and murder of Wilfred C. Sly and George J. Fanner and December 31, 1920. More about this can be found in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the chapter about Cuyahoga County.🕜

Brooklyn News was the neighborhood's newspaper.