Indian Museum of Lake County

Behind this unassuming door you will find the museum. It is Room A112.

The museum’s prized pipe collection.

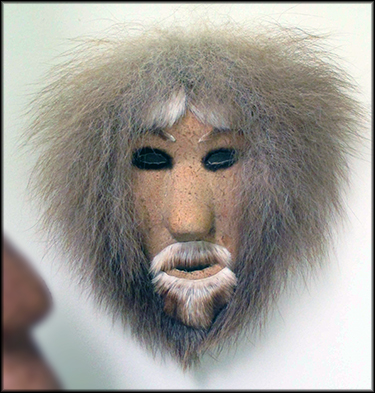

Caribou Mask Made by the Inuit

Bruno was only two years

of age when he was stuffed.

of age when he was stuffed.

Locating the Indian Museum of Lake County in Mentor, Ohio, was like going on an Easter egg hunt, except harder. My GPS brought me to a strip mall at which I saw neither the museum nor any signage for it. So I called it to ask for its specific location. I was told it was in the back. Which, it turned out, covered a lot of ground. The building in which it resides is a honeycomb of offices and commercial spaces. Even armed with the suite number, I still had trouble finding it, and it wasn’t until I saw small sign in a window that said “Indian Museum” that I finally found it.

About two miles east of the museum is land once owned by George S. Reeve. Since the 1800s it was known to have once been the location of a Native American settlement. Archeologists periodically dug there but no one excavated the entire site. When the property was sold to Marine Park Condominiums in 1973, trench digging for water and gas lines unearthed a large number of Native American artifacts. With no Ohio laws protecting these on private property—which, as of this writing, is still the case—and no interest by any major institutions to excavate it, it was up to amateur archeologists to save what they could within just a small window of time. What they unearthed became the core collection for the Indian Museum of Lake County. Those who had done the excavation also founded the Lake County Chapter of the Archeological Society of Ohio.

At first the chapter’s focus was on, of all things, pipes. Apparently the people who inhabited the site from about 900 c.e. to 1650 c.e. possessed a large number of these. During the quick dig before the condos were erected, about an unheard of fifty were uncovered. The Lake County Chapter wondered if others who had excavated the site previous to 1973 had unearthed any, so they began contacting any universities or museums that might have dug some up so as to do a complete inventory. It turned out over 200 have been found. The museum’s pipe collection is, I am told, the largest of its sort.

About two miles east of the museum is land once owned by George S. Reeve. Since the 1800s it was known to have once been the location of a Native American settlement. Archeologists periodically dug there but no one excavated the entire site. When the property was sold to Marine Park Condominiums in 1973, trench digging for water and gas lines unearthed a large number of Native American artifacts. With no Ohio laws protecting these on private property—which, as of this writing, is still the case—and no interest by any major institutions to excavate it, it was up to amateur archeologists to save what they could within just a small window of time. What they unearthed became the core collection for the Indian Museum of Lake County. Those who had done the excavation also founded the Lake County Chapter of the Archeological Society of Ohio.

At first the chapter’s focus was on, of all things, pipes. Apparently the people who inhabited the site from about 900 c.e. to 1650 c.e. possessed a large number of these. During the quick dig before the condos were erected, about an unheard of fifty were uncovered. The Lake County Chapter wondered if others who had excavated the site previous to 1973 had unearthed any, so they began contacting any universities or museums that might have dug some up so as to do a complete inventory. It turned out over 200 have been found. The museum’s pipe collection is, I am told, the largest of its sort.

The people who lived in the village are known as the Whittlesey Focus Culture, named after Colonel Charles Whittlesey because it was he who dug up many of their sites. This people lived in northern Ohio from around 900 c.e. to 1650 c.e. until the Seneca, members of the Iroquois Confederation, conquered their land. At that point the Whittlesey people probably assimilated into other tribes. According to one information sign, “they built their villages on bluffs above rivers including the Cuyahoga, Chagrin and Grand. They hunted, fished, and grew corn, squash, beans and pumpkins.”

Archeologists can make generalizations about how people lived, and sometimes learn about a specific individual if that person had a well stocked tomb, but even that is limited in what it reveals. Excavate the tomb of an important prehistoric Native American chief and you can learn only the most basic information about him: his age, how he died, diet, and so forth. Which is why I prefer history over archeology. History begins with written records, which can tell us so much more. Had this hypothetical chief been buried with the diary of his wife, we might have learned that he was murdered by a rival who envied his superior singing voice. This isn’t to diminish the importance of archeology, because it can tell us much, but it is most effective when combined with written records, which is why we know much about the ancient Egyptians.

Archeologists can make generalizations about how people lived, and sometimes learn about a specific individual if that person had a well stocked tomb, but even that is limited in what it reveals. Excavate the tomb of an important prehistoric Native American chief and you can learn only the most basic information about him: his age, how he died, diet, and so forth. Which is why I prefer history over archeology. History begins with written records, which can tell us so much more. Had this hypothetical chief been buried with the diary of his wife, we might have learned that he was murdered by a rival who envied his superior singing voice. This isn’t to diminish the importance of archeology, because it can tell us much, but it is most effective when combined with written records, which is why we know much about the ancient Egyptians.

The museum has expanded far beyond its original Reeve Village collection. Artifacts and more contemporary items from Native Americans across the United States can be found here, including those from Alaska. One of the museum’s purposes is to teach school children some basic facts about Native Americans such as whether they farmed, hunted, gathered, and so forth. It’s dry information that those interested can read about elsewhere. Children will nonetheless enjoy the museum because it offers at least one learning game and activities such as crushing corn.

No one knows what any of the prehistoric people who lived in Ohio called themselves, again for lack of written records. So they’ve been given retroactive names. The Hopewell, who inhabited southern Ohio from about 200 b.c. to 500 c.e., were named for the owners of a farm in Ross County, Ohio, where their mounds were first explored. The people who came after them, the Adena, were also mound builders and were originally credited with creating Serpent Mound in Peebles, Ohio, though that has since been disputed.

No one knows what any of the prehistoric people who lived in Ohio called themselves, again for lack of written records. So they’ve been given retroactive names. The Hopewell, who inhabited southern Ohio from about 200 b.c. to 500 c.e., were named for the owners of a farm in Ross County, Ohio, where their mounds were first explored. The people who came after them, the Adena, were also mound builders and were originally credited with creating Serpent Mound in Peebles, Ohio, though that has since been disputed.

The Indian Museum of Lake County serves as an excellent introduction to learning about Native Americans. Best of all, while most small museums are open at best a few days a week and only part of the year, you can visit this one seven days a week year round save for holidays and snow days. So if you happen to be in the Mentor area, stop by. It will take no more than an hour to go through.🕜

Smack dab in the middle of the museum’s section about the prehistoric Native people of Ohio is an out of place information sign about what one could trade beaver pelts for in 1774, these being used in Europe to make felt top hats. A single beaver pelt could get you, among other items, one kettle, twelve awl blades, two chisels, or 144 buttons. Twelve beaver pelts might purchase a gun, though what type is not mentioned. This tidbit of information came from the historical record.