Zoar Village

International Women's Air & Space Museum

This Fifinella (a female gremlin) nose art was created by Walt Disney for an adaptation of Roald Dalh’s novel The Gremlins. The movie was never made, but Disney did give the WASPs permission to use it as their mascot. It appeared on flight jacket patches.

This NASA console was used for the Apollo program.

The museum is found in this part of the concourse.

Inside the Museum

This figurine of Bessie Coleman was designed by sculptor Miss Martha (Martha Holcombe Root).

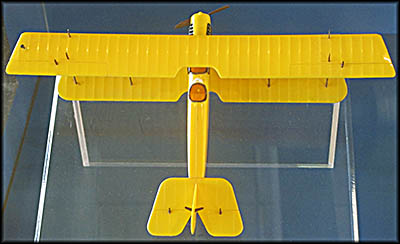

The model of a Jenny JN4 is the type of plane that Bessie Coleman flew.

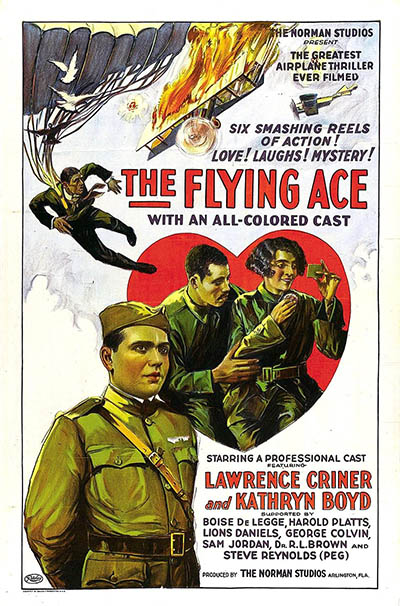

It's said Bessie Coleman inspire this all African American cast mystery/action thriller.

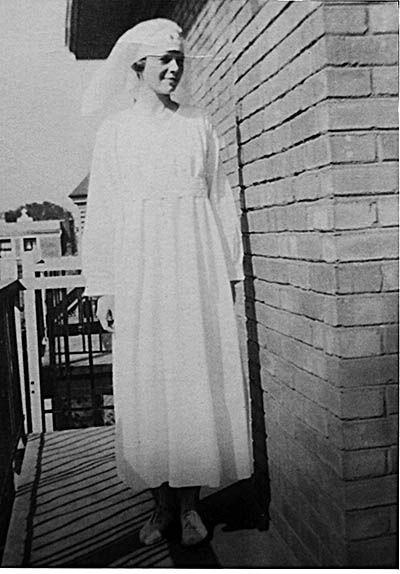

During World War I, Amelia Earhart volunteered as a nurse’s aid that, says the information sign, “she sewed herself.”

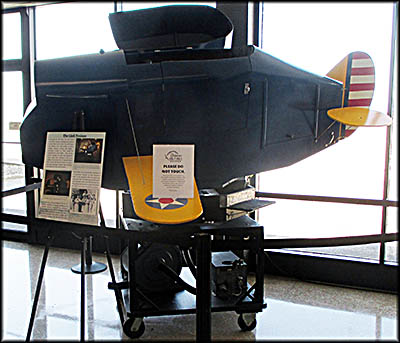

This is a model of the Lockheed Electra 10E Special, the airplane Amelia Earhart flew during her ill-fated attempt to fly around the world.

Amelia Earhart's Coveralls

This Ranger aircraft engine was made by the Fairchild Engine & Aircraft Co. in Farmingdale, New York.

Early Model Link Flight Simulator

GAT-1-A Flight Simulator

Tracy Pilurs, who earned her pilot's license in 1958, built the Pretty Purple Puddy Tat in her garage with help from her six children.

Women's Air Corps Uniform from World War II.

Douglas Adams once wrote, “It can hardly be a coincidence that no language on Earth has ever produced the expression ‘as pretty as an airport.’ Airports are ugly. Some are very ugly. Some attain a degree of ugliness that can only be the result of a special effort.” Cleveland’s Burke Lakefront Airport falls into this last category. It has a striking resemblance to a mall built in the 1960s complete with a vintage escalator, which was broken the day I visited.

Within the airport’s concourse you will find the International Women’s Air & Space Museum, which first opened in 1972 in Centerville, Ohio. Having outgrown this space, it moved to and reopened at Burke in 1999. Here I should warn that while the museum is free, parking isn’t, and the only way to pay is by using an unmanned credit card machine. If you don’t have a credit or debit card, you’ll want to park elsewhere or try getting away with parking along the curve. I was told there is another way out of the parking lot where you don’t have to pay, but I didn’t see it.

The museum’s exhibits are designed to integrate with the interior. This was done so well, if you enter via the east side, it’s not immediately apparent you are in a museum, even when looking down the main hallway. If I hadn’t known it was here, I might well have just passed the first exhibits.

Within the airport’s concourse you will find the International Women’s Air & Space Museum, which first opened in 1972 in Centerville, Ohio. Having outgrown this space, it moved to and reopened at Burke in 1999. Here I should warn that while the museum is free, parking isn’t, and the only way to pay is by using an unmanned credit card machine. If you don’t have a credit or debit card, you’ll want to park elsewhere or try getting away with parking along the curve. I was told there is another way out of the parking lot where you don’t have to pay, but I didn’t see it.

The museum’s exhibits are designed to integrate with the interior. This was done so well, if you enter via the east side, it’s not immediately apparent you are in a museum, even when looking down the main hallway. If I hadn’t known it was here, I might well have just passed the first exhibits.

As the museum’s name implies, it tells the stories of women who played prominent roles in air and space travel, though not necessarily as pilots. Wilbur and Orville Wright’s sister Katharine, as an example, gave her brothers much support during their time developing the first viable plane and, after its debut, helped to promote it. Upon Wilbur’s death, she became an officer in the Wright Company until its 1915 sale.

Sally Ride earned her doctorate in physics and one of her assignments during her flight on the space shuttle Challenger in July 1983 was to operate the shuttle’s robotic arm. Not only was she the first American woman in space, she served on the investigative board that looked in the Challenger’s explosion, and later on the one that looked into the Columbia’s breakup while reentering Earth’s atmosphere. She died of pancreatic cancer at the age of sixty-one on July 23, 2012, and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom the next year.

One display had brief biographical information about women involved in flight from around the world. This included Kyung O Kim, a remarkable woman who joined the Republic of Korea Air Force (South Korea) in 1948. During her seven year military career she did weather observation, radio operation, and spent five years flying classified documents to military airports. She left with the rank of captain and was the only female military pilot of that era. After becoming a civilian, she went to the United States where she earned her private pilot’s license. Upon returning to South Korea, she trained women to be pilots. Later she involved herself in organizations promoting aeronautics and women’s issues.

Sally Ride earned her doctorate in physics and one of her assignments during her flight on the space shuttle Challenger in July 1983 was to operate the shuttle’s robotic arm. Not only was she the first American woman in space, she served on the investigative board that looked in the Challenger’s explosion, and later on the one that looked into the Columbia’s breakup while reentering Earth’s atmosphere. She died of pancreatic cancer at the age of sixty-one on July 23, 2012, and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom the next year.

One display had brief biographical information about women involved in flight from around the world. This included Kyung O Kim, a remarkable woman who joined the Republic of Korea Air Force (South Korea) in 1948. During her seven year military career she did weather observation, radio operation, and spent five years flying classified documents to military airports. She left with the rank of captain and was the only female military pilot of that era. After becoming a civilian, she went to the United States where she earned her private pilot’s license. Upon returning to South Korea, she trained women to be pilots. Later she involved herself in organizations promoting aeronautics and women’s issues.

Edith Dizon from the Philippines was an accomplished concert pianist and organist who also taught at the Philippine Women’s University, and later became dean of Central Philippine University’s School of Music. The mother of seven children, she somehow found the time to get a pilot’s license—the first woman in the Philippines to do so. In 1967 she was invited by Lorraine McCarty to become one of four copilots, each one from a different country, for the 1967 Transcontinental Powder Puff Derby. Apparently these feats weren’t enough for her, so she went skydiving on her seventieth, seventy-fifth, and eightieth birthdays!

From the beginning of modern flight in 1903, women had an uphill battle to become pilots. In 1905 the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale formed to govern world air sports. In 1910 its members, which included the United States, made earning a pilot’s license mandatory for attending a flight school. This requirement gave male chauvinists the perfect way to keep women who weren’t already pilots from learning how to fly in the first place. Or at least tried to. In that same year, French baroness Raymonde de la Roche who was the first woman to earn a pilot’s license. Others would follow.

Bessie Coleman, a Black woman born in Texas, was denied entry to American flight schools because of her gender and race. Born on January 26, 1892, she was one of thirteen children. Like so many African Americans of her day, she migrated to the North to escape the staggering oppression of the Jim Crow South. She settled in Chicago in which racism was less blatant but just as insidious. Here she became a successful manicurist. Fascinated with the planes constantly flying overhead, she decided she wanted to be a pilot but, unable to gain entry to an American flight school, had to find an alternative. She learned French and headed to France in 1920 where she obtained her pilot’s license—the first Black woman to so.

From the beginning of modern flight in 1903, women had an uphill battle to become pilots. In 1905 the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale formed to govern world air sports. In 1910 its members, which included the United States, made earning a pilot’s license mandatory for attending a flight school. This requirement gave male chauvinists the perfect way to keep women who weren’t already pilots from learning how to fly in the first place. Or at least tried to. In that same year, French baroness Raymonde de la Roche who was the first woman to earn a pilot’s license. Others would follow.

Bessie Coleman, a Black woman born in Texas, was denied entry to American flight schools because of her gender and race. Born on January 26, 1892, she was one of thirteen children. Like so many African Americans of her day, she migrated to the North to escape the staggering oppression of the Jim Crow South. She settled in Chicago in which racism was less blatant but just as insidious. Here she became a successful manicurist. Fascinated with the planes constantly flying overhead, she decided she wanted to be a pilot but, unable to gain entry to an American flight school, had to find an alternative. She learned French and headed to France in 1920 where she obtained her pilot’s license—the first Black woman to so.

Arriving in the United States in September 1921, she became a stunt pilot and parachutist and took on the moniker “Queen Bess, Daredevil Aviatrix” at an airshow in Chicago the next year. Soon she was under contract to make a movie in New York City, but as an early and fierce advocate for equal rights, she walked off the set when it became apparent that the African American cast would be portrayed using the racist stereotypes typical of that era.

Returning the stunt flying, she crashed shortly after taking off from Santa Monica, California, when her newly purchased Jenny JN4 stalled at three hundred feet. Despite suffering from a broken leg and other injuries, she vowed to fly again. Recovering, she raised the money for a new two seat Jenny by opening a beauty parlor in Orlando, Florida. She planned to use her new plane at a May 1, 1926, show in Jacksonville, Florida. To that end, William D. Wills, a White mechanic, flew her new plane from Dallas to Jacksonville.

On April 28, the two took off in the plane so Bessie could look for a good jump sight for her skydiving act. Wills served as the pilot while Bessie sat in the back seat. A short woman, to see over the edge of the plane’s side, she had to unbuckle her seatbelt so she could stand up. This was her undoing. A loose wrench made its way into the engine, causing the plane to flip over and eject Colemen. She fell to her death, and Wills died when the plane crashed. It’s said that the 1926 movie The Flying Ace, which had an all Black cast, was somehow inspired by Coleman’s stunt work, but I wasn’t able to find a direct link.

Returning the stunt flying, she crashed shortly after taking off from Santa Monica, California, when her newly purchased Jenny JN4 stalled at three hundred feet. Despite suffering from a broken leg and other injuries, she vowed to fly again. Recovering, she raised the money for a new two seat Jenny by opening a beauty parlor in Orlando, Florida. She planned to use her new plane at a May 1, 1926, show in Jacksonville, Florida. To that end, William D. Wills, a White mechanic, flew her new plane from Dallas to Jacksonville.

On April 28, the two took off in the plane so Bessie could look for a good jump sight for her skydiving act. Wills served as the pilot while Bessie sat in the back seat. A short woman, to see over the edge of the plane’s side, she had to unbuckle her seatbelt so she could stand up. This was her undoing. A loose wrench made its way into the engine, causing the plane to flip over and eject Colemen. She fell to her death, and Wills died when the plane crashed. It’s said that the 1926 movie The Flying Ace, which had an all Black cast, was somehow inspired by Coleman’s stunt work, but I wasn’t able to find a direct link.

The most famous female pilot in history is without a doubt Amelia Earhart. Known mostly for her disappearance while flying around the world, she achieved much before her death, setting all sorts of records including the highest altitude in 1923, fastest speed (185.17 mph) in 1929, first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic in 1932 and the Pacific in 1935, and the first nonstop transcontinental flight in 1932. She and navigator Fred Noonan departed for their ill-fated flight around the world on May 21, 1937, and disappeared on July 2.

No woman tried to repeat this unaccomplished feat until 1964. When it did happen, Geraldine “Jerry” Mock and Joan Merriam Smith did it at the same time using different routes. Mock was first female to enter Ohio State’s aeronautical engineering program but, like so many young women of that era, she left the program to marry. She and her husband, Russell, settled in the Columbus suburb of Bexley and had three children. In 1958 she and Russell earned their pilot’s licenses together, then bought a single engine Cessna 180 they nicknamed “Charlie.”

Jerry decided to fly around the world. With financing from the newspaper Columbus Dispatch and the full support of her husband, she departed from Columbus in her plane the Spirit of Columbus on March 19, 1964. Her route around the world totaled 23,000 miles. It took her just twenty-nine days to complete her flight. The press dubbed her “The Flying Housewife.”

Two days before Mock’s departure, Smith, also called the “Flying Housewife,” took off from Oakland for her world-spanning flight. Unlike Mock, her goal was to follow Amelia Earhart’s route, so it took her longer to complete the trip because it consisted of more miles. As a result, she finished after Mock, depriving her of the title of being the first woman to fly solo around the world. Smith didn’t harbor any resentment against Mock, and it’s unlikely the supposed animosity between the two that the press stirred up was real.

No woman tried to repeat this unaccomplished feat until 1964. When it did happen, Geraldine “Jerry” Mock and Joan Merriam Smith did it at the same time using different routes. Mock was first female to enter Ohio State’s aeronautical engineering program but, like so many young women of that era, she left the program to marry. She and her husband, Russell, settled in the Columbus suburb of Bexley and had three children. In 1958 she and Russell earned their pilot’s licenses together, then bought a single engine Cessna 180 they nicknamed “Charlie.”

Jerry decided to fly around the world. With financing from the newspaper Columbus Dispatch and the full support of her husband, she departed from Columbus in her plane the Spirit of Columbus on March 19, 1964. Her route around the world totaled 23,000 miles. It took her just twenty-nine days to complete her flight. The press dubbed her “The Flying Housewife.”

Two days before Mock’s departure, Smith, also called the “Flying Housewife,” took off from Oakland for her world-spanning flight. Unlike Mock, her goal was to follow Amelia Earhart’s route, so it took her longer to complete the trip because it consisted of more miles. As a result, she finished after Mock, depriving her of the title of being the first woman to fly solo around the world. Smith didn’t harbor any resentment against Mock, and it’s unlikely the supposed animosity between the two that the press stirred up was real.

Mock and Smith probably spent of some of their time training as pilots in a flight simulator. The first commercially successful one was designed by American pilot Edwin Link. It came on the market in 1929. The museum has two of these, one of which, the “blue box,” is an original, and other is a replica put there so you can see inside the “cockpit.” The General Precision Equipment Company, which bought Link Aviation Company in 1954, continued to improve and update the simulator. One of its later models, the GAT-1-A from 1967, is also on display in the museum.

Beyond aviation and its many artifacts on display, the museum has quite a lot about the history of the space race and the involvement women had in it. The space race started after World War II when both the United States and Soviet Union grabbed as many former Nazi rocket scientists as they could. The Soviet launch of Sputnik in 1957 prompted the United States to found the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) which many of the Nazi scientists joined including former SS colonel Wernher von Braun.

In 1958, NASA asked Doctor Randolph Lovelace of the Dayton’s Aeromedical Field Laboratory at Wright Field to become chairman of its newly formed Special Advisory Committee on Life Sciences. Lovelace had previously overseen the development of an oxygen mask that allowed pilots to fly as high as 15,000 feet, which was needed for the U2 spy plane. At a facility in Alburquerque, New Mexico, Lovelace took a pool of thirty-one men to determine the qualifications needed to for a person to become an astronaut.

A forward-thinking fellow, he next rounded up female volunteers to go through the same testing. Called the Women in Space Program (later and incorrectly dubbed the Mercury 13), it was privately funded and not sanctioned by NASA. Most of its participants passed, so he arranged for further tests at the Naval Air Station in Pensacola, Florida. Someone in authority—no one seems to know who—caught wind of it and ordered its cancellation. Despite an appeal to Congress, the program never went further. The Soviets had no such inhibitions, and in 1963 they sent Valentina Tereshkova into space, making her the first woman to do so. Although the Apollo Program had no female astronauts, it nonetheless relied on women for its success. MIT software engineer Margaret Hamilton, as an example, led the team that programmed the mission’s guidance system. The museum has on display an Apollo-era NASA control console that it plans to restore so it can use its monitors to play archival footage.

Although the floor space the museum takes up isn’t especially large, it’s nonetheless jam-packed with far more information than I could summarize here, including extensive exhibits about women in World War II and female helicopter pilots.🕜

Beyond aviation and its many artifacts on display, the museum has quite a lot about the history of the space race and the involvement women had in it. The space race started after World War II when both the United States and Soviet Union grabbed as many former Nazi rocket scientists as they could. The Soviet launch of Sputnik in 1957 prompted the United States to found the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) which many of the Nazi scientists joined including former SS colonel Wernher von Braun.

In 1958, NASA asked Doctor Randolph Lovelace of the Dayton’s Aeromedical Field Laboratory at Wright Field to become chairman of its newly formed Special Advisory Committee on Life Sciences. Lovelace had previously overseen the development of an oxygen mask that allowed pilots to fly as high as 15,000 feet, which was needed for the U2 spy plane. At a facility in Alburquerque, New Mexico, Lovelace took a pool of thirty-one men to determine the qualifications needed to for a person to become an astronaut.

A forward-thinking fellow, he next rounded up female volunteers to go through the same testing. Called the Women in Space Program (later and incorrectly dubbed the Mercury 13), it was privately funded and not sanctioned by NASA. Most of its participants passed, so he arranged for further tests at the Naval Air Station in Pensacola, Florida. Someone in authority—no one seems to know who—caught wind of it and ordered its cancellation. Despite an appeal to Congress, the program never went further. The Soviets had no such inhibitions, and in 1963 they sent Valentina Tereshkova into space, making her the first woman to do so. Although the Apollo Program had no female astronauts, it nonetheless relied on women for its success. MIT software engineer Margaret Hamilton, as an example, led the team that programmed the mission’s guidance system. The museum has on display an Apollo-era NASA control console that it plans to restore so it can use its monitors to play archival footage.

Although the floor space the museum takes up isn’t especially large, it’s nonetheless jam-packed with far more information than I could summarize here, including extensive exhibits about women in World War II and female helicopter pilots.🕜

The dress on display that Katharine Wright wore is replica of the original created by high school student Jessica Syme for 4-H. The museum has the original but can no longer display it because it’s been damaged by light pollution and further exposure might me the end of this priceless artifact.