INVENTION OF IVORY SOAP

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

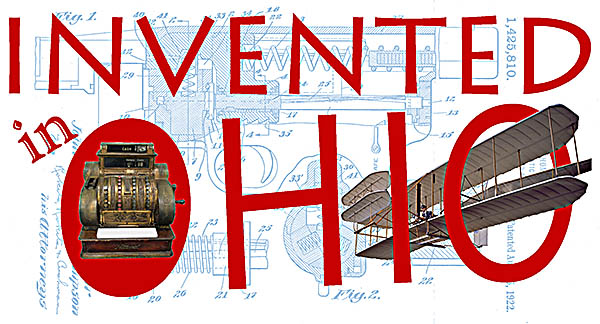

The very first ad for Ivory soap appeared in the Independent magazine.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

James Gamble. From Cincinnati: The Queen City.

Digitized by Google

Digitized by Google

William Procter. From Cincinnati: The Queen City.

Digitized by Google

Digitized by Google

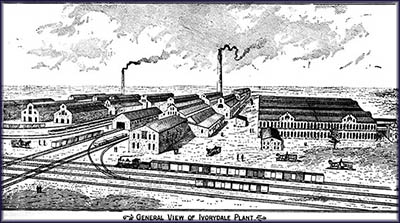

Ivorydale Plant in Cincinnati. From Illustrated to Cincinnati and the World's Columbia Exposition.

Digitized by Google.

Digitized by Google.

Elizabeth Drinker, wife of wealthy a Quaker, hadn’t fully immersed herself in water for 28 years. Now, at the age of 65, her husband had installed shower box in their Philadelphia home. The last time she’d dunked fully into a body of water was in 1771 at Bristol bath, a place several miles up the Delaware River from where she lived. Here it had taken her a week to work up the courage to make the plunge, and it was three more days before she tried it again. The experience had terrified her. In the intervening years it’s likely she did clean herself regularly via sponge baths, though this activity involved no soap. At this point, soap for use on the human body, known as toilet soap, hadn’t yet become a common article in America.

Like Mrs. Drinker, in the opening years of the nineteenth century most Americans refrained from bathing. Many thought it an unhealthy activity. Advocates to reverse this attitude frequently argued that regular bathing improved health, though few thought soap was necessary. Europeans were starting to use bath soap at this time, the best and most expensive being Castile, which was made from soda ash and olive oil. Soaps for other purposes usually consisted of cheaper ingredients including turpentine, rosin, and carbonate oil. One recipe that appeared in the August 15, 1853, issue of The Farmers’ Cabinet and American Herb-Book is typical for the type used for purposes other than body washing.

Like Mrs. Drinker, in the opening years of the nineteenth century most Americans refrained from bathing. Many thought it an unhealthy activity. Advocates to reverse this attitude frequently argued that regular bathing improved health, though few thought soap was necessary. Europeans were starting to use bath soap at this time, the best and most expensive being Castile, which was made from soda ash and olive oil. Soaps for other purposes usually consisted of cheaper ingredients including turpentine, rosin, and carbonate oil. One recipe that appeared in the August 15, 1853, issue of The Farmers’ Cabinet and American Herb-Book is typical for the type used for purposes other than body washing.

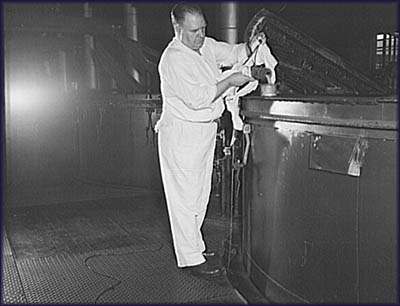

Worker at Proctor & Gamble's Cincinnati distribution taking a sample of soap from a vat. Photo by Howard R. Hollem, June 1943.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

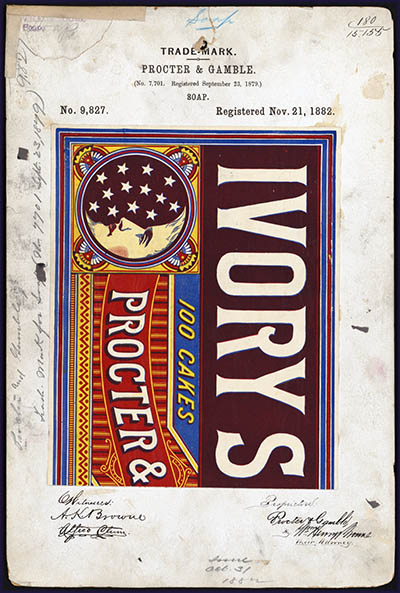

Ivory Soap Trademark, Nov. 21, 1882.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

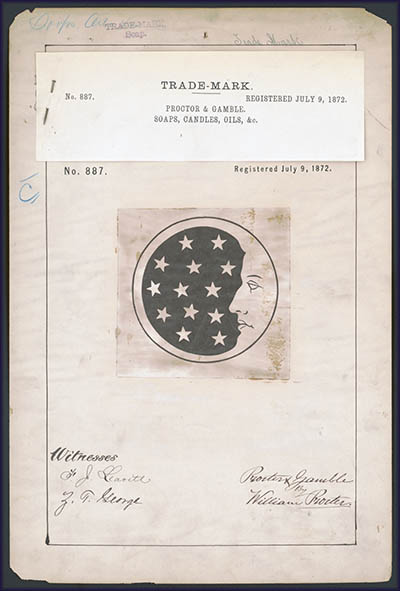

Proctor & Gamble Trademark, July 9, 1872.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the American attitude towards bathing changed from horror to seeing it as a necessity. It’s reasonable to think the change resulted from the influence of the American Protestant zeal stirred up by the Second Great Awakening, which lasted from about 1795 to 1835. After all, one of the prime movers of that movement were the Methodists, a religion cofounded by John Wesley. It was he who famously preached: “Cleanliness is, indeed, next to godliness.” Though Wesley probably paraphrased this from Sir Francis Bacon, it spawned the proverb “Cleanliness is next to godliness.” Wesley didn’t think physical cleanliness was a prerequisite for salvation, and it actually wasn’t the catalyst for changing why Americans saw bathing as a necessity. That transformation of attitudes can be laid squarely on the influence of social manners imported mainly from England that argued being physically clean made you morally and socially superior to those who weren’t.

By the time of the Civil War, middle class demand for toilet soap was such that a Cincinnati candle and soap making partnership, Procter & Gamble, decided to get into the business of making it. Up until this time the company produced two kinds of soap: No. 1 for deep scrubbing and No. 2 for washing clothes. Soap of this type shipped to grocers as huge slabs from which the amount desired was carved out. Toilet soaps on the market made domestically were usually made from Porkopolis tallow (hard pig fat), lard or grease with a caustic ingredient mixed in. Castile soaps sold for a premium. Procter & Gamble aimed to produce a soap superior to the tallow-based ones but much cheaper than Castile soaps.

By the time of the Civil War, middle class demand for toilet soap was such that a Cincinnati candle and soap making partnership, Procter & Gamble, decided to get into the business of making it. Up until this time the company produced two kinds of soap: No. 1 for deep scrubbing and No. 2 for washing clothes. Soap of this type shipped to grocers as huge slabs from which the amount desired was carved out. Toilet soaps on the market made domestically were usually made from Porkopolis tallow (hard pig fat), lard or grease with a caustic ingredient mixed in. Castile soaps sold for a premium. Procter & Gamble aimed to produce a soap superior to the tallow-based ones but much cheaper than Castile soaps.

That P&G resided in Cincinnati is due to happenstance. As a teenager, James A. Gamble, the company’s cofounder, had come to United States from Ireland with his family to escape the poverty caused by the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The family aimed to settle in Shawneetown, Illinois, but during their trip via flatboat down the Ohio, James became severely ill, forcing his father, George, to make an unplanned stop in Cincinnati while his son recovered. George Gamble liked the place so much, he decided to stay. Here he started a nursery. James apprenticed to a soap maker and by 1829 had opened his own soap-making factory.

An Englishman named William Procter moved to Cincinnati at the age of thirty on the advice of his friend William Hooper, whom he’d met while working in the clothing business in England. In Cincinnati, Procter started a candle making business and married Olivia Norris. James Gamble married her sister, Ann. When the Panic of 1837 struck, causing a major economic depression, Gamble’s and Procter’s father-in-law, Alexander Norris, suggested that his sons-in-law go into business together. This they did on October 31, 1837. It made sense from a production standpoint. At the time most mass produced soap and candles shared an ingredient: tallow. Initially a partnership, Procter took care of the store and Gamble oversaw the manufacturing. They were able to expand their market by shipping products on the Ohio River and, when it came to town in 1848, the railroad. In its first decades, candle making was the company’s primary business.

An Englishman named William Procter moved to Cincinnati at the age of thirty on the advice of his friend William Hooper, whom he’d met while working in the clothing business in England. In Cincinnati, Procter started a candle making business and married Olivia Norris. James Gamble married her sister, Ann. When the Panic of 1837 struck, causing a major economic depression, Gamble’s and Procter’s father-in-law, Alexander Norris, suggested that his sons-in-law go into business together. This they did on October 31, 1837. It made sense from a production standpoint. At the time most mass produced soap and candles shared an ingredient: tallow. Initially a partnership, Procter took care of the store and Gamble oversaw the manufacturing. They were able to expand their market by shipping products on the Ohio River and, when it came to town in 1848, the railroad. In its first decades, candle making was the company’s primary business.

On August 9, 1836, Ann Gamble bore James a son whom they named James Norris. After high school, James Norris attended Cincinnati’s Chickering Institute and, upon graduating from there, went to Kenyon College from which he earned a master’s degree in 1854. He did post-graduate work in chemistry at the University of Baltimore. In 1862 he joined his father’s firm as a worker, though he took time out to fight in the Civil War in the Squirrel Hunters, who were part of the home guard. James Norris supposedly gave a young inventor, Thomas Edison, his first “responsible” job. He tasked Edison with setting up a system of communication between P&G’s office and factory, which were two miles apart. Edison came up with an instrument containing dials and letters to serve this purpose.

James Norris began applying his knowledge of chemistry to the production of a vegetable-based soap as early as 1863 basing on a recipe he’d purchased. In that year he mentioned in his work journal that he’d made a floating soap, a characteristic he decided would be good for one made by P&G. This puts to rest the myth that a worker accidently left the stirring machine on too long, which in turned produced a floating soap by pushing extra air into the mix.

James Norris began applying his knowledge of chemistry to the production of a vegetable-based soap as early as 1863 basing on a recipe he’d purchased. In that year he mentioned in his work journal that he’d made a floating soap, a characteristic he decided would be good for one made by P&G. This puts to rest the myth that a worker accidently left the stirring machine on too long, which in turned produced a floating soap by pushing extra air into the mix.

It wasn’t until 1879 that P&G began selling James Norris’s invention. It was cheaper than Castile soap yet superior to tallow-based ones. Its primary ingredients were coconut and palm oils. At first it was to be called White Soap, then Harley T. Procter, William Procter’s son, heard Psalm 45:9, which said, “Myrrh and aloes, cassia, all thy garments, from the temples of ivory, by which they gladdened thee.” The word “ivory” resonated with Harley, so he decided to call the new soap by that name. That it floated was one of its early selling points. This was an exceedingly useful trait in an era when bathwater was shared by an entire family got mucky by the end of its use.

Harley took out a trademark on Ivory’s appearance that was issued on August 26, 1879. Its unique beveled top with slots made it visually appealing, and it was indented so that “Procter & Gamble” could be stamped into its top. The slot served more than aesthetics. It was there so the cake (as bars of soap were called in the business) could be broken in two. At its full nine-ounce size, Ivory was to be used as a laundry soap. When snapped in half, it became a bath soap.

Harley took out a trademark on Ivory’s appearance that was issued on August 26, 1879. Its unique beveled top with slots made it visually appealing, and it was indented so that “Procter & Gamble” could be stamped into its top. The slot served more than aesthetics. It was there so the cake (as bars of soap were called in the business) could be broken in two. At its full nine-ounce size, Ivory was to be used as a laundry soap. When snapped in half, it became a bath soap.

Harley designed Ivory’s package and in 1882 secured an unheard of $11,000 from the company board for advertising. Up until this time most advertising involved disreputable claims, so he went with a more reasonable one: “99 and 44/100 percent pure.” He started advertising in a grocer’s trade magazine in 1881. The next year an ad ran in the religious magazine The Independent. The massive advertising campaign P&G pursued for many years after made Ivory one of the most popular soaps in the United States. When the original factory that produced it burned down on January 7, 1884, the replacement was called Ivorydale.

Ivory ads became serialized. One was about Elizabeth Harding Bride whose husband considered leaving her because of a messy house. In the 1920s, P&G started a newspaper serial about an Ivory-using family named the Jollycos who were plagued by villainous neighbors. One ad that appeared in the August 4, 1922, issue of Illinois’ Rock Island Argus and Daily Union read:

Ivory ads became serialized. One was about Elizabeth Harding Bride whose husband considered leaving her because of a messy house. In the 1920s, P&G started a newspaper serial about an Ivory-using family named the Jollycos who were plagued by villainous neighbors. One ad that appeared in the August 4, 1922, issue of Illinois’ Rock Island Argus and Daily Union read:

The grease [from animals] is put into a cask, and strong lye added. During the year, as the fat increases, more lye is stirred in, and all occasionally stirred with a stick that is kept in it. By the time the cask is full, the soap is ready for use. It is made hard by boiling and adding a quart of fine salt to three gallons of soap. It is put into a tub to cool, and the froth scraped off. It is afterwards melted to a boiling heat, a little rosin or turpentine given, which improves the quality.

This concept jumped to the radio and thus was the soap opera born.

Ivory was produced in a kettle, a process that took two weeks complete. Sometime in the early 1930s, P&G engineer Victor Mills thought it might be more efficient to make it in a big vat stirred by paddles in the same way ice cream was made. His new machine reduced production time to two hours. Mills took his idea to P&G’s president, Richard Deupree, who’d been a salesman and didn’t understand the technical side of making soap. Mills told Dupree all the advantages of this new method as well as its one disadvantage: bars of soap made this way tended to disintegrate faster. Dupree immediately grasped this meant people would have to purchase it more often, so he authorized the change in manufacturing, which increased profits considerably.🕜

Ivory was produced in a kettle, a process that took two weeks complete. Sometime in the early 1930s, P&G engineer Victor Mills thought it might be more efficient to make it in a big vat stirred by paddles in the same way ice cream was made. His new machine reduced production time to two hours. Mills took his idea to P&G’s president, Richard Deupree, who’d been a salesman and didn’t understand the technical side of making soap. Mills told Dupree all the advantages of this new method as well as its one disadvantage: bars of soap made this way tended to disintegrate faster. Dupree immediately grasped this meant people would have to purchase it more often, so he authorized the change in manufacturing, which increased profits considerably.🕜

It seems that our troublesome, tricky neighbor, Mrs. Prowl, has managed to substitute some other soap for Teewee Jollyco’s private cake of Ivory. “To think anyone would be so mean to my little angel!” says Nurse Tippit, who is quite sentimental, though intelligent. “Ba-goo!” replies Teewee. And he is quite right—no self-respecting baby should endure a bath with a soap less pure and gentle than Ivory.