INVENTION OF THE AIRPLANE

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

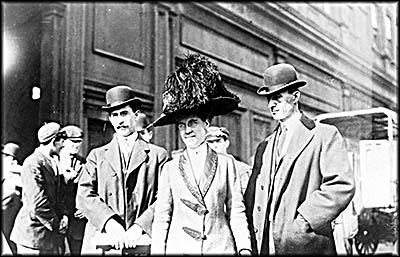

From left to right: Orville Wright, Katharine Wright and Orville Wright.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Samuel Langley's experimental plane in its original form never flew.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Wright Brothers' Plane in the Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith. Clipped by the author.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

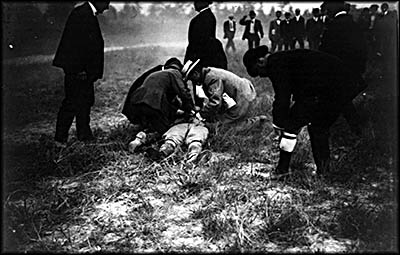

The remains of the Wright flyer after it's crash at Fort Meyer, Virginia.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

"Doctors with Lieutenant Selfridge"

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Orville Wright flying his plane. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

In 1900 two young men from Dayton wearing suits repeatedly climbed into what some mistook for a box kite and rode in it off the crest of a hill on Bodie Island, North Carolina. Sometimes it flew for 50 feet, maybe a bit more, but just as often it crashed, causing the man on board to roll into a ball and tumble down the side of a sandy hill. Coast guardsmen from the station at the southern end the island and residents of the fishing village of Kitty Hawk came to watch. Some found it amusing. The two Daytonians willingly flinging themselves off the hill were brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright. They’d come at the invitation of Kitty Hawk resident William Tate, who with his brother, Dan, provided assistance for this perceived folly.

What onlookers mistook for a box kite was a purpose-build glider made by the Wright brothers, the first one constructed by them to be tested near Kitty Hawk. It was one of the steps they took to reach the world’s first powered flight on December 17, 1903. That these two men of all people would accomplish it was remarkable. Neither had any formal training in science and Orville hadn’t even graduated from high school. They were by profession printers and bicycle mechanics. Their persistence and ability to discard bad science allowed them to do what others had tried and failed at.

Orville and Wilbur weren’t twins but might as well have been. Wilbur was Orville’s senior by four years, yet their voices were nearly identical as was their handwriting. They shared a bank account, lived in the same house, ate together, and even had a joint bank account. Neither married. Their interest in flight was sparked when their father gave them a toy helicopter in 1878. Intrigued, they built a scaled up version but it wouldn’t fly, so they abandoned it.

What onlookers mistook for a box kite was a purpose-build glider made by the Wright brothers, the first one constructed by them to be tested near Kitty Hawk. It was one of the steps they took to reach the world’s first powered flight on December 17, 1903. That these two men of all people would accomplish it was remarkable. Neither had any formal training in science and Orville hadn’t even graduated from high school. They were by profession printers and bicycle mechanics. Their persistence and ability to discard bad science allowed them to do what others had tried and failed at.

Orville and Wilbur weren’t twins but might as well have been. Wilbur was Orville’s senior by four years, yet their voices were nearly identical as was their handwriting. They shared a bank account, lived in the same house, ate together, and even had a joint bank account. Neither married. Their interest in flight was sparked when their father gave them a toy helicopter in 1878. Intrigued, they built a scaled up version but it wouldn’t fly, so they abandoned it.

The brothers came from a loving family. Their parents were Milton Wright and Susan Catherine, who encouraged their children to think for themselves. Milton was a bishop in the Church of the Brethren, which he ultimately broke with because he felt the leadership was too liberal. He started his own breakaway congregation, the Church of the United Brethren, Old Constitution, from which he was eventually forced to retire because of his contentiousness. Of the seven children his wife bore him, twins Otis and Ida died in infancy but the rest survived into adulthood. Daughter Katharine was a trained nurse who helped Orville and Wilbur with their effort to build an airplane, as did their brother Lorin. None of the Wright children had middle names.

Wilbur, born near Millville, Indiana, on April 16, 1867, moved with the rest of his family to Dayton in 1869. Upon graduating from high school, he planned to go to college to study theology with the idea of becoming a minister. An injury to his face suffered while playing a game of street hockey put an end to that, forcing him to convalesce for the next three years. In addition to that, his mother had tuberculosis and he nursed her until her untimely death in 1889.

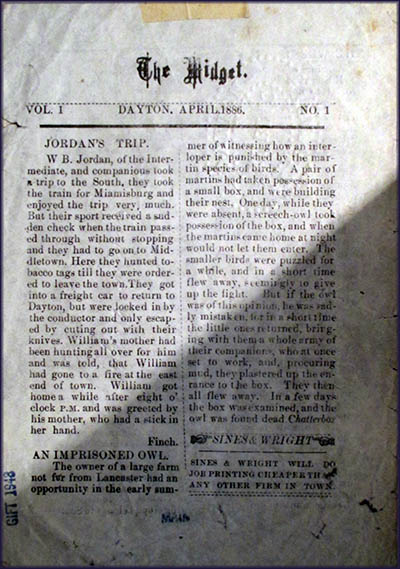

Orville, born in Dayton on April 19, 1871, showed a talent as artist. At the age of 15, he and his friend Edwin Sines started a printing business they called Sines & Wright. In 1886, they produced the first and only issue of the newspaper The Midget, which Wilbur’s father refused to let them distribute because he felt it was shoddy work. In 1896, Orville came down with typhoid fever. During his recovery he and Wilbur read about the gliding experiments of Otto Lilienthal in Germany, prompting the brothers to look into the topic further. One work they consulted was Professor Étienne-Jules Marey’s book Animal Mechanism: A Treatise on Terrestrial and Aërial Locomotion, which mentioned bird flight but didn’t go into much detail. The brothers read an ornithology book in 1899 that convinced them birds spent most of their time gliding, meant there was no reason humans couldn’t mimic this with some sort of device.

Wilbur, born near Millville, Indiana, on April 16, 1867, moved with the rest of his family to Dayton in 1869. Upon graduating from high school, he planned to go to college to study theology with the idea of becoming a minister. An injury to his face suffered while playing a game of street hockey put an end to that, forcing him to convalesce for the next three years. In addition to that, his mother had tuberculosis and he nursed her until her untimely death in 1889.

Orville, born in Dayton on April 19, 1871, showed a talent as artist. At the age of 15, he and his friend Edwin Sines started a printing business they called Sines & Wright. In 1886, they produced the first and only issue of the newspaper The Midget, which Wilbur’s father refused to let them distribute because he felt it was shoddy work. In 1896, Orville came down with typhoid fever. During his recovery he and Wilbur read about the gliding experiments of Otto Lilienthal in Germany, prompting the brothers to look into the topic further. One work they consulted was Professor Étienne-Jules Marey’s book Animal Mechanism: A Treatise on Terrestrial and Aërial Locomotion, which mentioned bird flight but didn’t go into much detail. The brothers read an ornithology book in 1899 that convinced them birds spent most of their time gliding, meant there was no reason humans couldn’t mimic this with some sort of device.

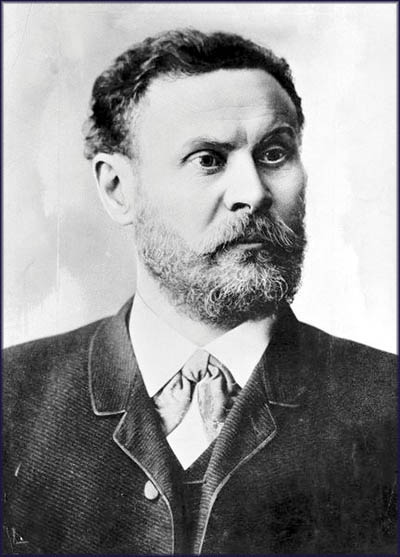

Lilienthal had the same idea. Having made his fortune alongside his brother operating a factory that produced small steam engines, he had plenty of money to build gliders. The very last he one he constructed and flew had a skin made out of balloon muslin soaked in collodion, a highly flammable chemical that helped keep air from passing through this cloth. His gliders usually weighed between 35 and 55 pounds and had a wingspan around 23 feet. He’d made thousands of successful flights with them, but changed on August 10, 1896. During a flight launched from off a hill near Rhinow, Germany, his glider crashed. He survived the initial impact but died shortly after in a hospital.

Knowing dangers like this existed, when Milton Wright learned of his sons’ plan to build an airplane, he said he approved but asked his sons never fly together. With the exception of one time in 1910, they kept this promise. Orville later claimed he and his brother decided to build a powered aircraft—they called it a flyer—for “sport.” Their motivation wasn’t to make money from it, but rather to raise money to continue their experiments by building gliders and, later, flyers. Orville didn’t think they’d ever get to the point where they could take out a patent.

This claim, written long after the airplane had been invented, was Orville rewriting he and his brother’s own history. From the beginning of their venture they planned to monetize it if possible and were extremely paranoid about protecting their ideas. On the Wright Flyer III, built in 1905, they painted the aluminum engine black so people would think it was made out of cast iron, and painted their plane’s propellers silver because the black and white photography of the day made it difficult to capture that color on film, rendering it virtually invisible.

Knowing dangers like this existed, when Milton Wright learned of his sons’ plan to build an airplane, he said he approved but asked his sons never fly together. With the exception of one time in 1910, they kept this promise. Orville later claimed he and his brother decided to build a powered aircraft—they called it a flyer—for “sport.” Their motivation wasn’t to make money from it, but rather to raise money to continue their experiments by building gliders and, later, flyers. Orville didn’t think they’d ever get to the point where they could take out a patent.

This claim, written long after the airplane had been invented, was Orville rewriting he and his brother’s own history. From the beginning of their venture they planned to monetize it if possible and were extremely paranoid about protecting their ideas. On the Wright Flyer III, built in 1905, they painted the aluminum engine black so people would think it was made out of cast iron, and painted their plane’s propellers silver because the black and white photography of the day made it difficult to capture that color on film, rendering it virtually invisible.

The brothers wrote to the Smithsonian Institution with a request for a list of literature that might help them learn more about flight. The Smithsonian obliged and sent them a number of pamphlets. To determine the best way to get lift, the brothers consulted air pressure tables created by the aforementioned Otto Lilienthal as well as Samuel P. Langley, a former secretary of the Smithsonian who had constructed his own powered aircraft machine, the Aerodrome, that never successfully flew with a pilot. Aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss modified Langley’s Aerodrome in 1914 to make it fly with a man on board. In its original form it crashed before getting aloft.

The Wrights began their initial experiments by building and flying box kites, which, when their usefulness came to end, they burned. Next they made a glider to determine if what they thought would work really did. For this they needed a place with heavy, consistent winds. Information published by the U.S. Weather Bureau told them an ideal place for this might be on North Carolina’s Bodie Island. Flights of their first glider there, such as they were, showed them that the Lilienthal and Langley tables were inaccurate. Upon returning home, they had the chief mechanic at their bicycle shop, Charles Taylor, build them a scaled down natural gas-powered wind tunnel. With this the brothers created their own air pressure tables.

They returned to Bodie Island in 1901 with a new glider and took to flight once more. This was a success. By now the brothers realized something no other aviation pioneer had yet to discover: shifting the weight of a pilot was not sufficient to stabilize a flying machine. Their solution was to develop wing warping—the bending of the wings to better control the pitch and roll of their flyer. Modern planes use on ailerons to achieve this.

The Wrights began their initial experiments by building and flying box kites, which, when their usefulness came to end, they burned. Next they made a glider to determine if what they thought would work really did. For this they needed a place with heavy, consistent winds. Information published by the U.S. Weather Bureau told them an ideal place for this might be on North Carolina’s Bodie Island. Flights of their first glider there, such as they were, showed them that the Lilienthal and Langley tables were inaccurate. Upon returning home, they had the chief mechanic at their bicycle shop, Charles Taylor, build them a scaled down natural gas-powered wind tunnel. With this the brothers created their own air pressure tables.

They returned to Bodie Island in 1901 with a new glider and took to flight once more. This was a success. By now the brothers realized something no other aviation pioneer had yet to discover: shifting the weight of a pilot was not sufficient to stabilize a flying machine. Their solution was to develop wing warping—the bending of the wings to better control the pitch and roll of their flyer. Modern planes use on ailerons to achieve this.

Upon completing their 1902 glider tests, the brothers decided to try powered flight the next year and to that end began constructing their first flyer for this purpose. They designed two propellers placed at the rear of the plane. The flyer needed a lightweight engine, but nothing on the market existed that would work, so they asked the talented Taylor if he’d build one. He readily agreed.

Taylor, born in a log cabin in Illinois on May 24, 1868, moved at the age of 24 to Kearney, Nebraska, to set up a machine shop. Here he met and married Henrietta Webbert, whose family was originally from Dayton. When family friend Milton Wright visited the Webberts, he suggested that Charlie move to Dayton because he’d find good work there as a mechanic. Taylor and his wife thought that was an excellent idea and relocated there in 1897. Henrietta’s uncle owned a building he rented to the Wright brothers, and it is this way Charlie became become acquainted with him. At the time Charlie worked for the Dayton Electric Company. The brothers offered to pay him $8 a more per week if he’d repair bikes for them. Katharine Wright, who managed the shop when her brothers were gone, disliked Charlie because he smoked cigars and had a “working class manner.”

Taylor was tasked by the Wrights to construct an engine that could produce eight horsepower yet was lighter than one normally would be with that much power. To reduce the weight, Charlie had a foundry cast the crankcase out of aluminum. After six weeks of work, he had a 12 horsepower engine ready. A battery was used to start the engine. The world’s first airplane engine was thus made in Dayton, Ohio, but Taylor rarely gets the credit he deserves as its inventor. He wasn’t even allowed to accompany the brothers to North Carolina for the first test flight because he was needed to keep the bike shop operating.

Taylor, born in a log cabin in Illinois on May 24, 1868, moved at the age of 24 to Kearney, Nebraska, to set up a machine shop. Here he met and married Henrietta Webbert, whose family was originally from Dayton. When family friend Milton Wright visited the Webberts, he suggested that Charlie move to Dayton because he’d find good work there as a mechanic. Taylor and his wife thought that was an excellent idea and relocated there in 1897. Henrietta’s uncle owned a building he rented to the Wright brothers, and it is this way Charlie became become acquainted with him. At the time Charlie worked for the Dayton Electric Company. The brothers offered to pay him $8 a more per week if he’d repair bikes for them. Katharine Wright, who managed the shop when her brothers were gone, disliked Charlie because he smoked cigars and had a “working class manner.”

Taylor was tasked by the Wrights to construct an engine that could produce eight horsepower yet was lighter than one normally would be with that much power. To reduce the weight, Charlie had a foundry cast the crankcase out of aluminum. After six weeks of work, he had a 12 horsepower engine ready. A battery was used to start the engine. The world’s first airplane engine was thus made in Dayton, Ohio, but Taylor rarely gets the credit he deserves as its inventor. He wasn’t even allowed to accompany the brothers to North Carolina for the first test flight because he was needed to keep the bike shop operating.

The brothers returned to Kill Devil Hills to test their new machine in September 1903. Nothing went right. First came a violent hurricane that nearly destroyed the shed in which they stored the flyer. After that passed, the wind remained too strong for flight for weeks. During the down time, the brothers invented a device to measure distance and an air speed indicator. On December 17, 1903, conditions were finally right for a test. Villagers from Kitty Hawk and the sailors from the coast guard station were invited to watch. Despite their desire for secrecy, the brothers knew they needed human witnesses watch what they hoped to achieve.

Orville won a coin toss to decide who’d fly first. The brothers asked John T. Daniels, who worked at the nearby weather station, to snap a photo. Taking off of a rail against a 27 mph wind, Orville flew at a speed of 33 mph for 120 feet. It wasn’t much, but no one had ever achieved powered flight carrying person before. Wilbur followed with a second flight. Orville returned to the pilot’s seat for the third successful flight. During the fourth with Wilber on board, the flyer was badly damaged during its landing, ending the session of flights that had lasted for one and a half hours.

The next day, wildly inaccurate stories based on an Associated Press wire report appeared in newspapers across the United States. Vermont’s Barre Daily Times, for example, proudly proclaimed in its headline that the Wrights’ “airship” had flown three miles with the wind behind it. It gave Wilbur was given credit for the first flight. The story reported that one propellor was vertical and the other horizontal with the mistaken belief that the horizontal one kept the plane aloft while the vertical one pushed it forward. The airship, it said, was nothing more than a box kite. Appalled, the brothers wrote to the AP to correct a few things. The plane flew into the wind, not against it. It had launched off a monorail track with a length of about 40 feet. The plane had flown as close to the ground as possible in case of a crash. The farthest flight went just over half a mile.

Orville won a coin toss to decide who’d fly first. The brothers asked John T. Daniels, who worked at the nearby weather station, to snap a photo. Taking off of a rail against a 27 mph wind, Orville flew at a speed of 33 mph for 120 feet. It wasn’t much, but no one had ever achieved powered flight carrying person before. Wilbur followed with a second flight. Orville returned to the pilot’s seat for the third successful flight. During the fourth with Wilber on board, the flyer was badly damaged during its landing, ending the session of flights that had lasted for one and a half hours.

The next day, wildly inaccurate stories based on an Associated Press wire report appeared in newspapers across the United States. Vermont’s Barre Daily Times, for example, proudly proclaimed in its headline that the Wrights’ “airship” had flown three miles with the wind behind it. It gave Wilbur was given credit for the first flight. The story reported that one propellor was vertical and the other horizontal with the mistaken belief that the horizontal one kept the plane aloft while the vertical one pushed it forward. The airship, it said, was nothing more than a box kite. Appalled, the brothers wrote to the AP to correct a few things. The plane flew into the wind, not against it. It had launched off a monorail track with a length of about 40 feet. The plane had flown as close to the ground as possible in case of a crash. The farthest flight went just over half a mile.

While this experiment—for that was what it was—proved once and for all that powered flight could be done, it was no airplane. The brothers’ goal was to produce a machine that could manage sustained flight for a long period over much distance, and to do it safely. The 1903 flyer had served its purpose and never flew again. It now resides in the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. The brothers had no intention of marketing their machine until was perfected. During a trip someone asked Wilbur how much one would cost. Wilber remarked to a friend with him: “I hope I can make a living without murdering people. I am working out an aeroplane idea. I haven’t worked it out yet. I need the money, but I won’t make it murdering people with a half developed machine.”

For their 1904 experiments, they constructed a completely new plane out of heavier materials and used an 18 horsepower engine. The new flyer had modified rudders. They took it to Huffman Prairie outside of Dayton near the Simms Station trolley stop. Tests began on May 26. They flew it in circles. To increase stability, in June they moved the center of gravity by shifting the locations of the radiator, gas tank and engine. They did a total of 105 tries at flight that year, the longest lasting five minutes. The average speed was 38 mph. At the end of the season, they kept the propellers and burned the airframe.

The next year, the brothers assembled a new plane in a building on Huffman Prairie. This model included new features such as rudder control and independent wing warping. The 1904 plane had flown continuously in a circle for one mile. This new one could go for 24 miles at heights of 75 to 100 feet and would have stayed aloft longer had its fuel not run out. With it they made over 50 flights. It qualifies as the world’s first successful airplane and can be seen in the Wright Brothers National Museum, which is part of Carillon Historical Park in Dayton, Ohio. It’s the flyer upon which their commercially sold planes would be based.

For their 1904 experiments, they constructed a completely new plane out of heavier materials and used an 18 horsepower engine. The new flyer had modified rudders. They took it to Huffman Prairie outside of Dayton near the Simms Station trolley stop. Tests began on May 26. They flew it in circles. To increase stability, in June they moved the center of gravity by shifting the locations of the radiator, gas tank and engine. They did a total of 105 tries at flight that year, the longest lasting five minutes. The average speed was 38 mph. At the end of the season, they kept the propellers and burned the airframe.

The next year, the brothers assembled a new plane in a building on Huffman Prairie. This model included new features such as rudder control and independent wing warping. The 1904 plane had flown continuously in a circle for one mile. This new one could go for 24 miles at heights of 75 to 100 feet and would have stayed aloft longer had its fuel not run out. With it they made over 50 flights. It qualifies as the world’s first successful airplane and can be seen in the Wright Brothers National Museum, which is part of Carillon Historical Park in Dayton, Ohio. It’s the flyer upon which their commercially sold planes would be based.

The Wrights wrote to their congressman, Robert M. Nevin, to see if the U.S. government was interested in purchasing their invention. Nevin replied with an enclosed letter from Major General G.L. Gillespie, who wrote on behalf of the Board of Ordnance and Fortification. His answer: unless the machine was working and its development cost the government nothing, the U.S. Army wasn’t interested.

In November 1905, the brothers wrote to the French ambassador in Washington, D.C., informing him that they’d succeeded with powered flight two years ago and now had a machine they could sell to France. If the ambassador doubted what they’d done, they assured him there were plenty of witnesses. This got them nowhere, but in 1906 a French business syndicate showed interest, mainly because its own efforts to produce a working plane had failed. It sent representatives to America to see the plane for themselves. They loved what they saw and asked for an option to buy the patent rights.

Those running the syndicate disregarded their representatives’ opinion and declined to proceed. Undaunted, Wilbur boldly took the 1905 flyer to France itself to show it off there. At Camp d’Avours, near Le Mans, he flew for 91 minutes. In 1909, Orville and Katharine brought a plane to Germany for the same purpose during which she flew as a passenger.

By 1907, the U.S. Army had changed its mind about airplanes. At this time others such as Glenn Curtiss had gotten their own airplanes into the air, so competition existed. The Army offered a contract of $25,000 for a powered aircraft that could fly a minimum of 40 mph for at least 125 miles before refueling. Achieving anything above these criteria would earn a bonus. The plane also had to carry both a pilot and passenger upright. The Wrights modified their 1905 design to accommodate these requested changes, plus introduced a new 35 horsepower engine that sat vertical instead of horizontal. A new set of pilot controls was introduced. The plane weighted 1,500 pounds, had two rudders, and its engine used an early form of fuel injection rather than a carburetor. The brothers felt the best way to launch an airplane was by putting it on runners, necessitating a monorail track for takeoff.

In November 1905, the brothers wrote to the French ambassador in Washington, D.C., informing him that they’d succeeded with powered flight two years ago and now had a machine they could sell to France. If the ambassador doubted what they’d done, they assured him there were plenty of witnesses. This got them nowhere, but in 1906 a French business syndicate showed interest, mainly because its own efforts to produce a working plane had failed. It sent representatives to America to see the plane for themselves. They loved what they saw and asked for an option to buy the patent rights.

Those running the syndicate disregarded their representatives’ opinion and declined to proceed. Undaunted, Wilbur boldly took the 1905 flyer to France itself to show it off there. At Camp d’Avours, near Le Mans, he flew for 91 minutes. In 1909, Orville and Katharine brought a plane to Germany for the same purpose during which she flew as a passenger.

By 1907, the U.S. Army had changed its mind about airplanes. At this time others such as Glenn Curtiss had gotten their own airplanes into the air, so competition existed. The Army offered a contract of $25,000 for a powered aircraft that could fly a minimum of 40 mph for at least 125 miles before refueling. Achieving anything above these criteria would earn a bonus. The plane also had to carry both a pilot and passenger upright. The Wrights modified their 1905 design to accommodate these requested changes, plus introduced a new 35 horsepower engine that sat vertical instead of horizontal. A new set of pilot controls was introduced. The plane weighted 1,500 pounds, had two rudders, and its engine used an early form of fuel injection rather than a carburetor. The brothers felt the best way to launch an airplane was by putting it on runners, necessitating a monorail track for takeoff.

Inside the replica of the Wright Bike Shop at Carollin Historical Park in Dayton, Ohio.

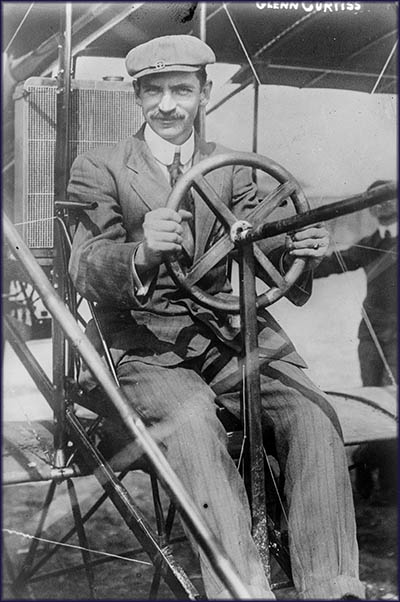

Glenn Curtiss

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Otto Lilienthal

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Orville Wright and his friend Edward Sines never distrubuted their newspaper, The Midget, because Orville's father considered it "shoddy work."

Carollin Historical Park

Carollin Historical Park

Samuel P. Langley

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

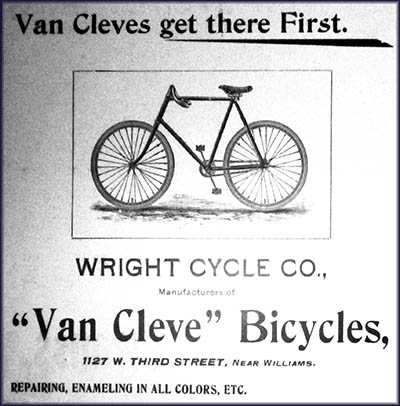

Ad for The Van Cleve bike, which Orville and Wilbur briefly produced.

Carollin Historical Park

Carollin Historical Park

This is a replica of the workshop at at Carollin Historical Park in Dayton, Ohio. It is here where the Wrights designed and built parts of their ariplanes. In the foreground is the wind tunnel.

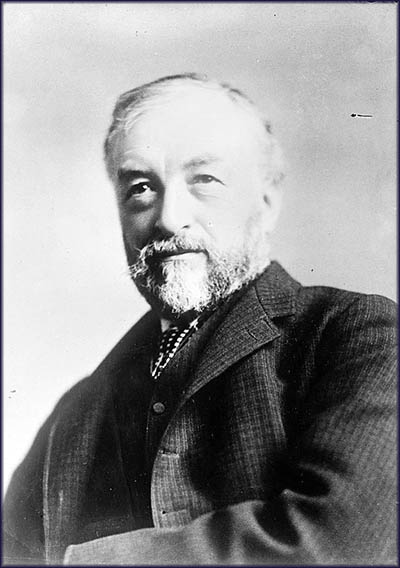

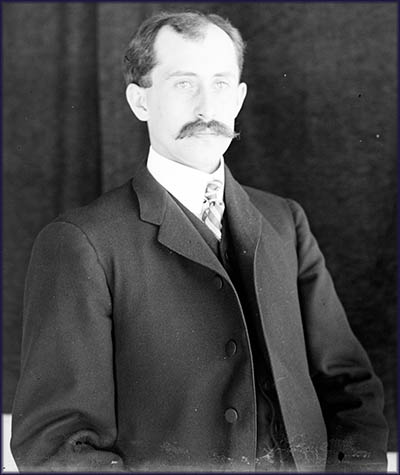

Wilbur Wright, Age 38

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

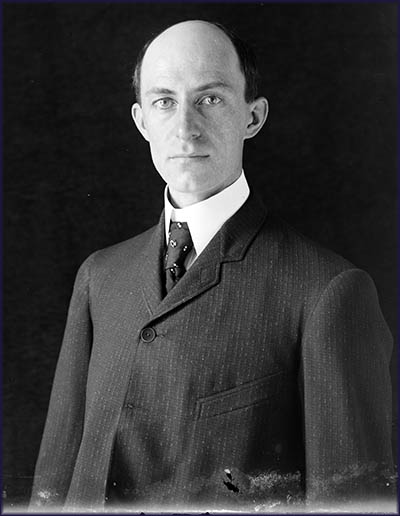

Orville Wright, Age 34

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Otto Lilienthal Gliding Experiment

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Kill Devil Hills with Wright Monument

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

In mid-September 1908, Orville took the plane to Fort Myer in Virginia to demonstrate it to the Army. On September 14 he achieved a height of 200 feet, a record for any aircraft then flying. Three days later, he took to the air with passenger Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge. During this flight one of the propellers broke. Orville frantically tried to bring the plane under control but before he could do so, it crashed. Orville suffered from a broken thigh and ribs as well as many bruises, wounds that would plague him the rest of his life. Selfridge received a fracture to his skull and lacerations his head and face. Knocked unconscious, he died in a hospital three hours later without ever waking, making him the first person killed in an airplane crash.

Despite this mishap, the Army bought the Wright plane. And because it went 42 mph, a bonus was thrown in to make the contract worth $30,000. In 1909, the brothers started a flying school and their own business to build planes, the Wright Company. Other aviation pioneers would introduce innovations never seen on the Wright planes, such as wheels for landing and a propeller at the plane’s front.

Wilbur stopped flying altogether in 1910 to concentrate on defending he and his brother’s patents. He was quite bitter that others had infringed upon them. It was during a trip to Boston to defend said patents that he came down with the typhoid fever that killed him on May 30, 1912. Orville would continue this work, and it wouldn’t be until 1917 that he finally stopped his efforts. In 1918 a settlement was made with other aviation concerns because the United States had entered World War I and the government needed its airplane manufacturers to focus on making new machines, not fighting one another in court. Orville once estimated that he and his brother spent $152,000 in patent litigation.🕜

Despite this mishap, the Army bought the Wright plane. And because it went 42 mph, a bonus was thrown in to make the contract worth $30,000. In 1909, the brothers started a flying school and their own business to build planes, the Wright Company. Other aviation pioneers would introduce innovations never seen on the Wright planes, such as wheels for landing and a propeller at the plane’s front.

Wilbur stopped flying altogether in 1910 to concentrate on defending he and his brother’s patents. He was quite bitter that others had infringed upon them. It was during a trip to Boston to defend said patents that he came down with the typhoid fever that killed him on May 30, 1912. Orville would continue this work, and it wouldn’t be until 1917 that he finally stopped his efforts. In 1918 a settlement was made with other aviation concerns because the United States had entered World War I and the government needed its airplane manufacturers to focus on making new machines, not fighting one another in court. Orville once estimated that he and his brother spent $152,000 in patent litigation.🕜