Invention of the Automotive Electric Starter

INVENTION OF THE AUTOMOTIVE ELECTRIC SELF-STARTER

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

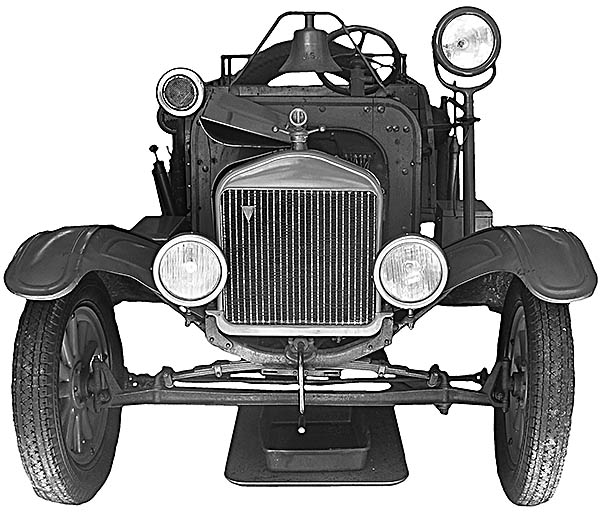

Model T with Crank Starter

Model T Musuem, Mishler Mill Campus, Pioneer Village.

Model T Musuem, Mishler Mill Campus, Pioneer Village.

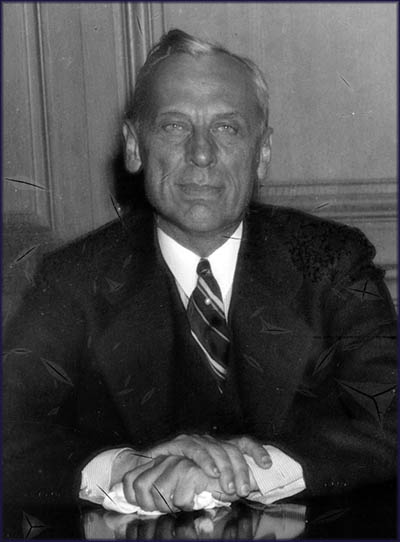

Charles E. Kettering (left) and William S. Knudsen (right) in Washington, D.C., on December 6, 1938.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Cranking a Model T

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

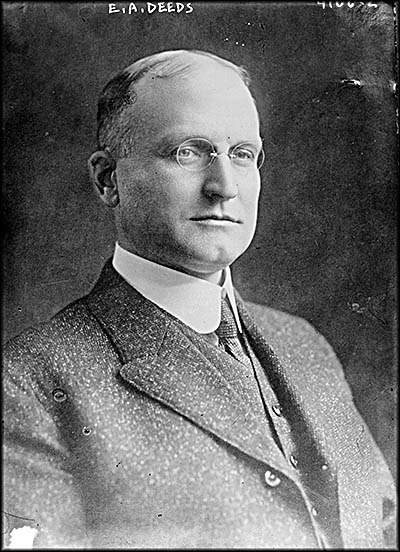

Edward A. Deeds. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

William Crapo Durant. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

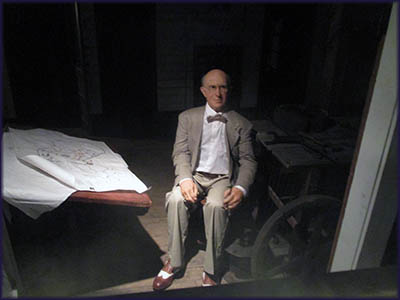

Thomas Midgley, Jr.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

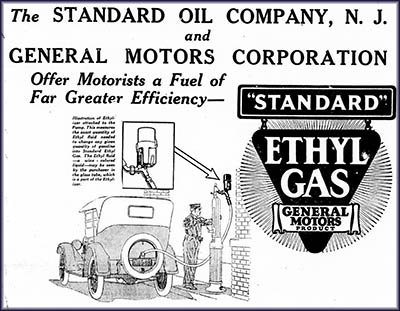

Ethyl Gas Ad

Chronicling America. Library of Congress

Chronicling America. Library of Congress

July 1909: Hart Collins of Albion, Iowa, broke his arm while cranking his father’s car. August 1910: W.S. Marshall of Baraboo, Wisconsin, lost his grip on the crank of his car, resulting in a bloody, broken nose. October 1906: while starting a car, its crank struck machinist Chris Frees in his groin. He worked at the Raritan Auto and Motor Garage in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, and thought little of it at the time of impact. However, by the next day his groin had become swollen, causing excruciating pain. August 1909: Will Douglas broke his arm while trying to start his father’s car. May 1901: David A. Eagles of Salina, Kansas, started his son-in-law’s five-passenger car so he could put it in the garage. The car took off on its own, pinning Eagles to the back of the garage and severing one of his legs. He bleed to death.

Insurance companies took note of this and other car-related injuries. In the August 24, 1912, issue of Automobile Topics, it was reported that “companies are complaining that the rapid development of the automobile and its greatly increased use have resulted in an alarming increase in the losses paid to insured automobilists.… The insurance people themselves do not seem to want to attack the automobile as such, and admit that the greater number of claims do not come from the reckless use of the machine.” Injuries increased mainly because so many more cars were now on the road. Still, when breaking down the different types of auto-related injuries, which included “looking at auto[,] caught finger in speedometer” and “pushing auto of out garage, wheel ran over foot,” only injuries caused by crank-starting a car merited subcategories.

While there was clearly a need for a self-starting system that eliminated the crank altogether, no one seemed to be able to crack the problem. A variety of methods had been tried using chemistry, mechanics, and electricity, but none worked reliably. The man who came up with a solution, Charles Kettering, was born on August 29, 1876, in Loudonville, Ohio. After graduating at the top of his high school class, he attended the College of Wooster for a time until an eye inflammation caused him to drop out. During his time recuperating, he worked as a telephone lineman. After returning to college, he graduated from Ohio State University at the age of 28 and immediately went to work for National Cash Register (NCR) in Dayton for which he invented the electric cash register.

Insurance companies took note of this and other car-related injuries. In the August 24, 1912, issue of Automobile Topics, it was reported that “companies are complaining that the rapid development of the automobile and its greatly increased use have resulted in an alarming increase in the losses paid to insured automobilists.… The insurance people themselves do not seem to want to attack the automobile as such, and admit that the greater number of claims do not come from the reckless use of the machine.” Injuries increased mainly because so many more cars were now on the road. Still, when breaking down the different types of auto-related injuries, which included “looking at auto[,] caught finger in speedometer” and “pushing auto of out garage, wheel ran over foot,” only injuries caused by crank-starting a car merited subcategories.

While there was clearly a need for a self-starting system that eliminated the crank altogether, no one seemed to be able to crack the problem. A variety of methods had been tried using chemistry, mechanics, and electricity, but none worked reliably. The man who came up with a solution, Charles Kettering, was born on August 29, 1876, in Loudonville, Ohio. After graduating at the top of his high school class, he attended the College of Wooster for a time until an eye inflammation caused him to drop out. During his time recuperating, he worked as a telephone lineman. After returning to college, he graduated from Ohio State University at the age of 28 and immediately went to work for National Cash Register (NCR) in Dayton for which he invented the electric cash register.

NCR’s assistant general manager, Edward A. Deeds, who lived in a mansion on Dayton’s Central Avenue, began building a kit car in a barn on his property that served as a carriage house. Deeds wanted to replace the car’s hand crank starter with an electric motor. Realizing cars at this time couldn’t generate enough power to run it, he asked his friend Kettering for some help. This turned into a project to create a better ignition system to maintain the spark needed to keep an internal combustion engine running. Most ignition systems produced a shower of sparks powered by dry cell batteries that quickly lost their charge. Kettering, still at NCR, borrowed an oscillograph from work to study this phenomenon.

He built a magnetic relay set to only release a spark when necessary. For additional help, he brought in two fellow workers from NCR, his assistant William A. Chryst and electrical technician William P. Anderson. Because Kettering still worked at NCR, he sometimes arrived at Deed’s barn in disguise complete with a beaver cap. More NCR employees joined and those involved in the project became known as the Barn Gang. Out of this work Kettering invented the ignition coil, which produced a high voltage burst of energy sufficient to power the spark plugs, which was far better than the magneto being used at the time. Kettering made a generator to provide more power as well as a voltage regulator. Three days before filing for a patent for his ignition coil on September 15, 1909, he quit his job at NCR. Deeds approached the head of Cadillac, Henry Martyn Leland, to see if he’d be interested in buying ignition coils for his vehicles.

He built a magnetic relay set to only release a spark when necessary. For additional help, he brought in two fellow workers from NCR, his assistant William A. Chryst and electrical technician William P. Anderson. Because Kettering still worked at NCR, he sometimes arrived at Deed’s barn in disguise complete with a beaver cap. More NCR employees joined and those involved in the project became known as the Barn Gang. Out of this work Kettering invented the ignition coil, which produced a high voltage burst of energy sufficient to power the spark plugs, which was far better than the magneto being used at the time. Kettering made a generator to provide more power as well as a voltage regulator. Three days before filing for a patent for his ignition coil on September 15, 1909, he quit his job at NCR. Deeds approached the head of Cadillac, Henry Martyn Leland, to see if he’d be interested in buying ignition coils for his vehicles.

Leland, a Quaker born in Barton, Vermont, on February 16, 1843, had perfectionism instilled in him by his parents. He believed that doing something the right way was also the most economical thing to do. When the Civil War broke out, he left his job as a mechanic at a loom works to take a job at the Springfield Armory. Here he made a lathe so good he was offered to run the armory itself.

After the war, he went back into the private sector. He left his employer, Brown and Sharpe, in 1890, then moved to Detroit. Here he met lumber man Robert C. Faulconer. He desperately needed access to a machine shop, so he, Leland, and Charles H. Norton formed a partnership to start one. Called Leland, Faulconer & Norton, it started up on September 19, 1890. Leland was made the firm’s vice president. He hired his son, Wilfred, because he, too, was a talented machinist. Together father and son, according to Leland biographers Maurice D. Hendry and John Heilig, “made precision a religion in the factory.” When Norton departed in 1894, the company became known as Leland and Faulconer. It specialized in precision made gears and expanded into making internal combustion and steam engines.

In August 1902, Oldsmobile, which operated in Lansing, asked the company to build 2,000 engines. Leland, seeing its many inefficiencies, decided to rework Ransom Olds’s original design into something much improved. Oldsmobile rejected it because the redesign would have to forced it to retool its factory plus update its cars’ chassis while simultaneously trying to fill back orders created by a recent fire in the plant. Leland’s schematic lay fallow until two men, Lemuel W. Bowen and William Murphy, visited him at his office later that year with a proposition. The car company they’d founded with Henry Ford as its chief engineer had failed. Could Leland appraise the plant and equipment so it could be sold off?

After the war, he went back into the private sector. He left his employer, Brown and Sharpe, in 1890, then moved to Detroit. Here he met lumber man Robert C. Faulconer. He desperately needed access to a machine shop, so he, Leland, and Charles H. Norton formed a partnership to start one. Called Leland, Faulconer & Norton, it started up on September 19, 1890. Leland was made the firm’s vice president. He hired his son, Wilfred, because he, too, was a talented machinist. Together father and son, according to Leland biographers Maurice D. Hendry and John Heilig, “made precision a religion in the factory.” When Norton departed in 1894, the company became known as Leland and Faulconer. It specialized in precision made gears and expanded into making internal combustion and steam engines.

In August 1902, Oldsmobile, which operated in Lansing, asked the company to build 2,000 engines. Leland, seeing its many inefficiencies, decided to rework Ransom Olds’s original design into something much improved. Oldsmobile rejected it because the redesign would have to forced it to retool its factory plus update its cars’ chassis while simultaneously trying to fill back orders created by a recent fire in the plant. Leland’s schematic lay fallow until two men, Lemuel W. Bowen and William Murphy, visited him at his office later that year with a proposition. The car company they’d founded with Henry Ford as its chief engineer had failed. Could Leland appraise the plant and equipment so it could be sold off?

Leland took a look at what they had and proposed that rather than close the plant, the directors should use it to manufacture his improved Oldsmobile engine. To this they agreed. The revived company was capitalized at $300,000 and named Cadillac in honor of French pioneer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, founder of what would one day become the city of Detroit. Leland was made one of the company’s directors and given some stock. He would allow nothing but perfectly fitted parts to be used and gladly scrapped anything even a few thousandths of an inch out of spec. No car left the factory that didn’t meet his exacting standards. That he ordered 5,000 of Kettering’s ignition coils in July 1909 showed just how impressed he was with this new invention.

Deeds and Kettering formed Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company (later shortened to Delco), which was incorporated on July 22, 1909. Deeds secured a $100,000 loan to start it, the liability of which was his and Kettering’s. After incorporation, stock was offered to raise more capital. It was supposed to be an invention house, yet Delco was expected to build the coils for Cadillac. To meet the order, it contracted the Kellogg Company to make and deliver them.

Delco next turned to developing an electric self-starter for autos to replace the old hand crank system. One story says that Leland asked it to be developed it because the death of his good friend Byron J. Carter, founder of Cartercar. In 1910, Carter supposedly came across a woman whose car had stalled on a the bridge to Belle Isle in the Detroit River. While trying to start her vehicle, the crank flew off, seriously hurting him. Several weeks later he died of his injury. The trouble with this is that Carter had died two years earlier of pneumonia, and his Detroit Times obituary mentioned nothing about starting a car. Possibly there is grain of truth to this story, but it’s more likely apocryphal or a mix up with another man whose last name was Carter.

Deeds and Kettering formed Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company (later shortened to Delco), which was incorporated on July 22, 1909. Deeds secured a $100,000 loan to start it, the liability of which was his and Kettering’s. After incorporation, stock was offered to raise more capital. It was supposed to be an invention house, yet Delco was expected to build the coils for Cadillac. To meet the order, it contracted the Kellogg Company to make and deliver them.

Delco next turned to developing an electric self-starter for autos to replace the old hand crank system. One story says that Leland asked it to be developed it because the death of his good friend Byron J. Carter, founder of Cartercar. In 1910, Carter supposedly came across a woman whose car had stalled on a the bridge to Belle Isle in the Detroit River. While trying to start her vehicle, the crank flew off, seriously hurting him. Several weeks later he died of his injury. The trouble with this is that Carter had died two years earlier of pneumonia, and his Detroit Times obituary mentioned nothing about starting a car. Possibly there is grain of truth to this story, but it’s more likely apocryphal or a mix up with another man whose last name was Carter.

Kettering and his compatriots began working on this project in the Deeds Barn on September 2, 1910. Kettering built a motor that would be powered by a light-weight battery made by O. Lee Harrison from Philadelphia’s Electric Storage and Battery Company. The first successful test occurred on February 16, 1911. The starter was integrated with a car’s lighting and ignition system, which is why the patent was called an “Engine Starting, Lighting, and Ignition System” rather than just a self-starter. It derived its initial power from a car battery. In July 1911, Cadillac decided to use the new starters on its 1912 model. In November, Delco received an order of 12,000. Finding no shops willing to manufacture an untested invention, Kettering and Deeds were forced to rent space at the Beaver Power Building so Delco itself could make them.

In 1916, William Crapo Durant bought Delco and made it part of his new company, United Motors. Durant had previously founded General Motors but was ousted as its head in 1910. The sale of Delco to United Motors made Kettering a millionaire several times over. In the same year that Durant bought Delco, he also regained control of GM and ultimately integrated all of United Motors’ companies into it.

GM officially absorbed Delco in 1918. It became part of General Motors Research Corporation over which Kettering was made vice-president on the conditions that he didn’t possess authority, couldn’t be held responsible for company products, and wasn’t answerable to how much money was spent. Research labs, he said, needed to have that sort of independence so the business of inventing could go on unimpeded. “Boss” Kettering and his research division became masters of “planned obsolescence,” the business of adding new upgrades to GM’s cars each year to make the previous years’ model less desirable. In addition to the ignition coil and electric self-starter, Kettering also invented a two-cycle Diesel engine and fast-drying lacquer paint. When his lab moved to Detroit in 1924, he remained in Dayton, although he traveled frequently to Detroit where he lived in a luxurious hotel.

A very practical man, he came off as a folksy sort of fellow whom you couldn’t help but like. But another invention made at his direction leaves a serious blot on his reputation. Cadillac owners complained that their engines knocked and blamed it on the new-fangled self-starter. Kettering directed a research assistant named Thomas Midgley, Jr. to investigate the cause. Having no idea what it might be, Midgley started experimenting. Soon he found that adding iodine to gasoline removed the knocking, establishing that fuel was the culprit.

The iodine worked because it increased the fuel’s octane, which eliminated the knocking by preventing the premature explosion of the fuel and air mix. While useful for identifying the problem, iodine had corrosive properties that made it useless for a permanent fix. An alternative additive to boost octane was needed, so Kettering had the lab investigate this as well. Soon enough it was found that adding ethyl alcohol stopped the knocking. A mixture of this and gasoline seemed the likely direction to go. GM spent four years investigating this type of fuel mixture and concluded it worked well.

GM’s founder, Durant, was ousted from the company in 1920 for a second time and replaced with Alfred P. Sloan, who put the squeeze on Kettering’s department. It needed to start making money—or else. GM had yet to come up with a patentable anti-knock fuel nor a way to procure a steady supply of alcohol for gasoline to reach the necessary 30 percent part of the mix with gasoline. The du Pont family, which controlled about 30 percent of GM and had significant oil interests, wanted more oil in its fuel and demanded an alternative. Kettering told Midgley to find something within the next two weeks. Though it took him till 1921, he found that adding tetraethyl lead significantly reduced engine knock. Better still, it only took one part of this to 1,000 parts of gasoline to do it. But, as had been known for 3,000 years and the National Lead Company admitted to in 1921, lead was a deadly poison.

In 1916, William Crapo Durant bought Delco and made it part of his new company, United Motors. Durant had previously founded General Motors but was ousted as its head in 1910. The sale of Delco to United Motors made Kettering a millionaire several times over. In the same year that Durant bought Delco, he also regained control of GM and ultimately integrated all of United Motors’ companies into it.

GM officially absorbed Delco in 1918. It became part of General Motors Research Corporation over which Kettering was made vice-president on the conditions that he didn’t possess authority, couldn’t be held responsible for company products, and wasn’t answerable to how much money was spent. Research labs, he said, needed to have that sort of independence so the business of inventing could go on unimpeded. “Boss” Kettering and his research division became masters of “planned obsolescence,” the business of adding new upgrades to GM’s cars each year to make the previous years’ model less desirable. In addition to the ignition coil and electric self-starter, Kettering also invented a two-cycle Diesel engine and fast-drying lacquer paint. When his lab moved to Detroit in 1924, he remained in Dayton, although he traveled frequently to Detroit where he lived in a luxurious hotel.

A very practical man, he came off as a folksy sort of fellow whom you couldn’t help but like. But another invention made at his direction leaves a serious blot on his reputation. Cadillac owners complained that their engines knocked and blamed it on the new-fangled self-starter. Kettering directed a research assistant named Thomas Midgley, Jr. to investigate the cause. Having no idea what it might be, Midgley started experimenting. Soon he found that adding iodine to gasoline removed the knocking, establishing that fuel was the culprit.

The iodine worked because it increased the fuel’s octane, which eliminated the knocking by preventing the premature explosion of the fuel and air mix. While useful for identifying the problem, iodine had corrosive properties that made it useless for a permanent fix. An alternative additive to boost octane was needed, so Kettering had the lab investigate this as well. Soon enough it was found that adding ethyl alcohol stopped the knocking. A mixture of this and gasoline seemed the likely direction to go. GM spent four years investigating this type of fuel mixture and concluded it worked well.

GM’s founder, Durant, was ousted from the company in 1920 for a second time and replaced with Alfred P. Sloan, who put the squeeze on Kettering’s department. It needed to start making money—or else. GM had yet to come up with a patentable anti-knock fuel nor a way to procure a steady supply of alcohol for gasoline to reach the necessary 30 percent part of the mix with gasoline. The du Pont family, which controlled about 30 percent of GM and had significant oil interests, wanted more oil in its fuel and demanded an alternative. Kettering told Midgley to find something within the next two weeks. Though it took him till 1921, he found that adding tetraethyl lead significantly reduced engine knock. Better still, it only took one part of this to 1,000 parts of gasoline to do it. But, as had been known for 3,000 years and the National Lead Company admitted to in 1921, lead was a deadly poison.

Midgley falsely claimed it would not be a hazard to people and the environment despite having suffered from acute lead poisoning in January 1923. Kettering knew how toxic lead was, too, but having spent the last three years expending a fortune on a failed air-cooled engine that nearly bankrupted GM, he backed Midgley’s lie. As a result, despite many alternatives that could work just as well if not better, lead was added to gasoline and not completely banned in the U.S. until 1986. The last leaded gas in the world was sold in July 2021.

Midgley wasn’t done wrecking the environment. In 1928 General Motors, which owned Frigidaire, made him head of a team tasked with inventing a safer coolant that, if it leaked, would do no harm. Out of this came dichlorodifluoromethane, which was marketed as Freon-12. Midgley demonstrated how “safe” it was by breathing it and snuffing out a candle by exhaling onto it. It was the world’s first chlorofluorocarbon (CFC), destroyer of the ozone layer.🕜

Midgley wasn’t done wrecking the environment. In 1928 General Motors, which owned Frigidaire, made him head of a team tasked with inventing a safer coolant that, if it leaked, would do no harm. Out of this came dichlorodifluoromethane, which was marketed as Freon-12. Midgley demonstrated how “safe” it was by breathing it and snuffing out a candle by exhaling onto it. It was the world’s first chlorofluorocarbon (CFC), destroyer of the ozone layer.🕜

Alfred P. Sloan

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

The curved dash Olds for which Henry Leland designed an updated engine.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Henry Leland (left) and President Calvin Coolidge (right). Harris & Ewing, 1927.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Hayloft in the Deeds Barn at Carillon Historical Park, Dayton, Ohio

Fridaire Display at the Carillon Historical Park, Dayton, Ohio.

Altantic Ethyl Pump in Leola, Pennsylvania.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress