INVENTION OF THE GAS MASK

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

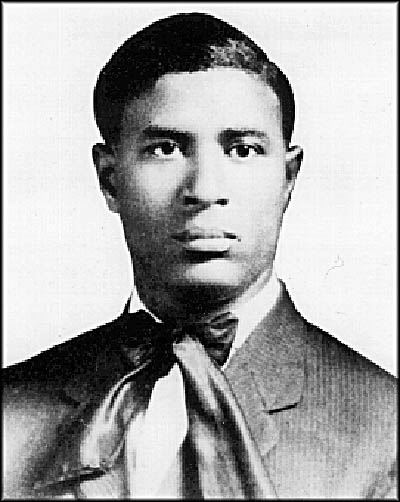

Garrett A. Morgan

U.S. Department of Transporation

U.S. Department of Transporation

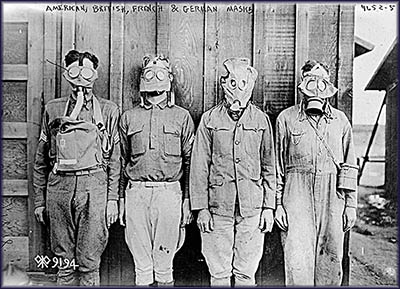

World War I gas masks from (left to right) American, British, French and German.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

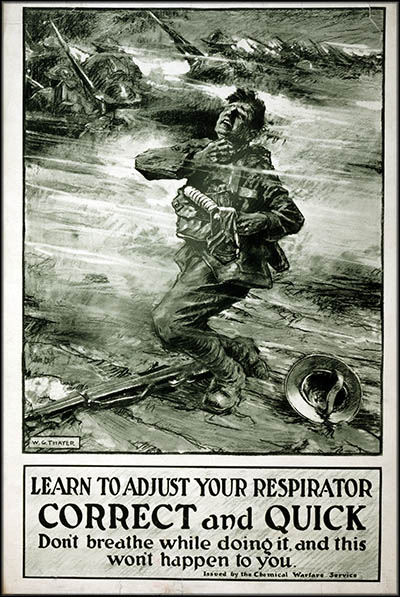

Chemical Warfare Service Poster from World War I

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

When your phone rings at four in the morning, it’s not likely to be good news. Garrett A. Morgan learned this first hand on July 25, 1916. On the other end of the line was a policeman, who’d called to ask if Morgan would please bring 20 to 25 of his safety hoods to the West 9th Street Pier. There’d been an accident in a tunnel being dug under Lake Erie and men were trapped. Morgan woke his brother, Frank, to come with him. With the help of neighbor William Roots, they loaded twenty hoods into Garrett’s car, then hurried to the pier. There the Morgan brothers climbed on board the tug Wallace, which took them three and a half miles to the water intake plant known as Crib No. 5.

The fact that someone had called Morgan for help is remarkable considering he was the son of Kentucky slaves in an era when discrimination against Blacks was no better in Cleveland than in the South. Morgan was born on March 4, 1877, in Claysville, Kentucky, the “colored” section of the large town of Paris. Morgan’s grandfather on his father’s side was none other than John Hunt Morgan, the man who led a raid into Ohio during the Civil War. Garrett’s mother, the daughter of a preacher, was half Native American.

Morgan dropped out of school in the sixth grade and headed to Cincinnati. Here he became a handyman. In 1895 he moved to Cleveland, where he lived until his death on July 27, 1963. He had 10 cents in his pocket upon arriving in the city, and he went to work for a sewing machine manufacturer as a janitor. There he showed an aptitude for fixing the machines, and in 1909 established a tailor shop where he employed thirty people. A year earlier he’d married the Bohemian-born Mary Anne Hasek with whom he had three children. While rare, interracial marriages did exist in the United States and Ohio was one state where it’d been legalized in 1887.

Morgan dropped out of school in the sixth grade and headed to Cincinnati. Here he became a handyman. In 1895 he moved to Cleveland, where he lived until his death on July 27, 1963. He had 10 cents in his pocket upon arriving in the city, and he went to work for a sewing machine manufacturer as a janitor. There he showed an aptitude for fixing the machines, and in 1909 established a tailor shop where he employed thirty people. A year earlier he’d married the Bohemian-born Mary Anne Hasek with whom he had three children. While rare, interracial marriages did exist in the United States and Ohio was one state where it’d been legalized in 1887.

Morgan invented a sewing machine operated by a foot-pedal. At his shop he needed to solve the problem of sewing machines scorching wool, so he mixed a variety of chemicals to alleviate the problem. One night after working on a formula, he cleaned his hands on pony hair before going to dinner. Upon returning he found it was standing up. Seeing the potential for this, Morgan, whose son described him as “jolly but quick-tempered [who] … also had his stern moments,” tried it on the neighbor’s Airedale dog. Sure enough, its hair stood up. Morgan’s son recalled, “The dog looked so different, the neighbor didn’t recognize his own dog.” Throughout his life the bulk of Morgan’s income came from this hair straightener formula, a product produced by his business G.A. Morgan Hair Refining Cream Company.

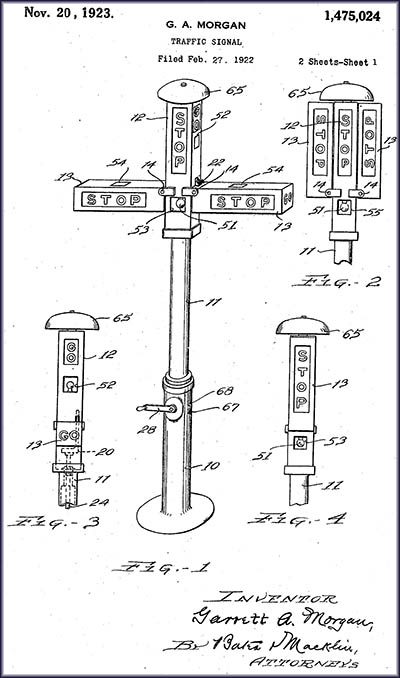

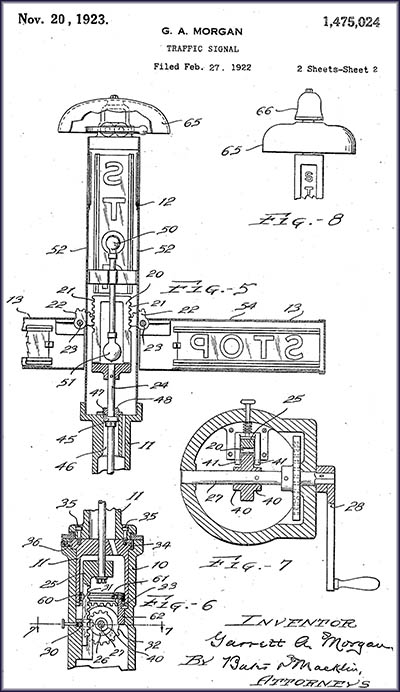

Although refining cream paid the bills, Morgan had a passion to create devices that improved safety. As a boy Morgan had seen a friend drown and it became something of his mission in life to create safety devices. Once, for example, after witnessing a car hit a horse, he invented a traffic signal that he patented in 1923. Illuminated by electric lightbulbs powered either by batteries or overhead electrical wires, it had two semaphore signs that said, “Go” and “Stop.” An operator changed the signal with a hand crank. General Electric bought the patent for $40,000.

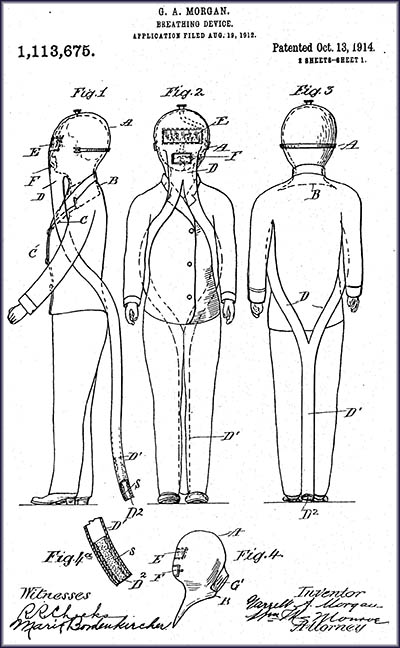

Morgan invented the gas mask in 1912. It consisted of an airtight helmet made of rubber or asbestos or whatever type of material suited the environment for which it was intended. It had a tight fitting collar to keep out noxious gases. It could be put on and used immediately. From the hood snaked two rubber tubes that went under the arms and merged into a single tube in which a sponge filled with water was placed to filter out dangerous gases. The tube was near ground level because the majority of dangerous gases were lighter than fresh air. It could be changed to go upward if the opposite were true, such as when dealing with the mustard gas used widely a few years later during World War I.

Although refining cream paid the bills, Morgan had a passion to create devices that improved safety. As a boy Morgan had seen a friend drown and it became something of his mission in life to create safety devices. Once, for example, after witnessing a car hit a horse, he invented a traffic signal that he patented in 1923. Illuminated by electric lightbulbs powered either by batteries or overhead electrical wires, it had two semaphore signs that said, “Go” and “Stop.” An operator changed the signal with a hand crank. General Electric bought the patent for $40,000.

Morgan invented the gas mask in 1912. It consisted of an airtight helmet made of rubber or asbestos or whatever type of material suited the environment for which it was intended. It had a tight fitting collar to keep out noxious gases. It could be put on and used immediately. From the hood snaked two rubber tubes that went under the arms and merged into a single tube in which a sponge filled with water was placed to filter out dangerous gases. The tube was near ground level because the majority of dangerous gases were lighter than fresh air. It could be changed to go upward if the opposite were true, such as when dealing with the mustard gas used widely a few years later during World War I.

The wearer exhaled through a separate tube that held a ball which rose as the air exited and lowered to seal the opening while the user inhaled. To ensure the wearer could hear others, the hood came with a pair of ear trumpets, one on each side. A piece of mica served as its lens so the user could see out. Mica had the added advantage of tolerating heat and being easy to clean.

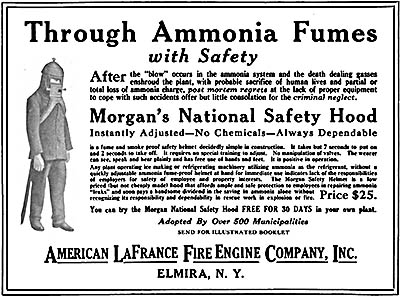

The commercial version had a few minor changes from the original patent description. Ice and Refrigeration reported “it consists of a canvas and rubber hood that can be quickly slipped over the head and shoulders, being secured to the throat. It is fitted with isinglass [mica] from ports. The supply of fresh air is secured through a rubber hose which hangs to the floor.… The wearer can prevent smoke or gas from entering the intake of the helmet at any time.” Enough air filled the large helmet to give the wearer fifteen minutes’ worth of unpolluted air. The hood weighted three and a half pounds. It sold for a reasonable $25.

The commercial version had a few minor changes from the original patent description. Ice and Refrigeration reported “it consists of a canvas and rubber hood that can be quickly slipped over the head and shoulders, being secured to the throat. It is fitted with isinglass [mica] from ports. The supply of fresh air is secured through a rubber hose which hangs to the floor.… The wearer can prevent smoke or gas from entering the intake of the helmet at any time.” Enough air filled the large helmet to give the wearer fifteen minutes’ worth of unpolluted air. The hood weighted three and a half pounds. It sold for a reasonable $25.

To market and manufacture it, Morgan founded the National Safety Device Company funded in large part by his Black friends. They made a wise investment. Between 1914 and 1916, the company’s stock went from $10 to $250 a share. Morgan never called his device a gas mask. It was sold as Morgan’s National Safety Hood. He went on the road to sell it. While touring in the South, he disguised himself as a Canadian Native American known as Big Chief Mason and had his white friend, Charles P. Salan, pose as him. It was a sound strategy. Whenever someone in that region learned the device’s inventor was Black, sales were lost.

In New Orleans, Morgan, posing as Big Chief Mason, demonstrated how well his hood worked by entering a tent in which burned a mixture of formaldehyde, burning pitch and sulphur that became so thick a search light shined into it penetrated no more than three feet. Morgan stayed inside for 20 minutes with no ill-effects. At the Second International Exposition of Safety and Sanitation in New York City, he won the grand prize. New York’s fire department adopted it as did those of 500 other cities. Morgan sold it to the U.S. Navy after demonstrating it on a submarine. During World War I the U.S. Army used an improved version of it.

As of July 24, 1916, Morgan’s hometown of Cleveland hadn’t yet purchased any of his hoods. For this and a lack of other basic safety precautions, the city would receive much criticism during the investigation of the tunnel explosion. The tunnel was just one of several that the city had under Lake Erie. Cleveland started getting its drinking water from the lake in 1856, but by late 1860s sewage and other hazardous substances harmful to human life had so polluted Cleveland’s shoreline, it wasn’t safe to drink that water. This prompted the city to dig a tunnel under the lake that reached about a mile out where the water wasn’t tainted. Pollution soon reached that point, too, so in 1898 the city dug a second tunnel three miles under the lake. In March 1914 work on a much longer third tunnel began. It was during the excavating of this one that the explosion had occurred.

In New Orleans, Morgan, posing as Big Chief Mason, demonstrated how well his hood worked by entering a tent in which burned a mixture of formaldehyde, burning pitch and sulphur that became so thick a search light shined into it penetrated no more than three feet. Morgan stayed inside for 20 minutes with no ill-effects. At the Second International Exposition of Safety and Sanitation in New York City, he won the grand prize. New York’s fire department adopted it as did those of 500 other cities. Morgan sold it to the U.S. Navy after demonstrating it on a submarine. During World War I the U.S. Army used an improved version of it.

As of July 24, 1916, Morgan’s hometown of Cleveland hadn’t yet purchased any of his hoods. For this and a lack of other basic safety precautions, the city would receive much criticism during the investigation of the tunnel explosion. The tunnel was just one of several that the city had under Lake Erie. Cleveland started getting its drinking water from the lake in 1856, but by late 1860s sewage and other hazardous substances harmful to human life had so polluted Cleveland’s shoreline, it wasn’t safe to drink that water. This prompted the city to dig a tunnel under the lake that reached about a mile out where the water wasn’t tainted. Pollution soon reached that point, too, so in 1898 the city dug a second tunnel three miles under the lake. In March 1914 work on a much longer third tunnel began. It was during the excavating of this one that the explosion had occurred.

The tunnel superintendent of construction was Gus Van Duzen. On Sunday, July 24, one of his men, Jack Johnston, arrived at Van Duzen’s house. Jack, who was experiencing acute confusion because of the gas he’d inhaled, was described by Van Duzen as “dopey.” Jack warned that there was natural gas in the tunnel. Van Duzen went to the site and told crew boss Harry Vokes to vent the gas out and wait until midnight before resuming work. Vokes defied the order and at Crib No. 5 he and men descended at 8 p.m. Work resumed, and a terrible explosion buried the crew under mud and debris.

Those who made the first attempt to effect a rescue all fell unconscious from the gas. A second attempt was led by Van Duzen himself. Seeing his fellow rescuers started to collapse, he told one of his men, Martin Nelson, to get everyone out. Van Duzen fell to the floor, unconscious, injuring his hip. When those above realized the second rescue party wasn’t going to be returning, someone remembered Morgan’s new safety hood and thought it would be a good idea to get a few of them.

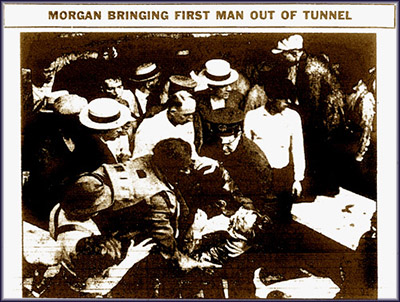

Few men were keen on volunteering for a third rescue attempt. Someone asked Morgan if he would go down. He agreed without hesitation, and along with Frank, Tom Clancy and Gilbert Martin Via, he took an elevator down 111 feet. He came across a door behind which he could hear pounding. Unable to open it, he smashed its glass window, retrieved a man behind, and brought him to the surface. The rescuers brought up two living men—one being Van Duzen—and four bodies. Cleveland’s mayor, waiting on the surface, congratulated Morgan.

Ten rescuers perished as did 12 tunnel diggers for a total of 22. Morgan’s heroism was virtually erased from the historical record. No newspaper this author could find mentioned his name save for one article in the African American newspaper The Monitor published in Omaha, Nebraska. The Cleveland Plain Dealer named the heads of the third rescue party as D.J. Parker and L.M. Jones. Much praise was heaped upon Van Duzen. Because of lingering gas, the effort to find twelve men who’d been buried temporarily stopped until all the gas could be vented out of the tunnel.

City Hall launched a probe into the disaster with idea of putting the blame on Vokes, Van Duzen, Johnston, and a city chemist for his failure to take a timely test for gas in the tunnel. Witnesses told a different story, pointing out that a lack of necessary equipment such as a telephone line had been the real cause. These unwanted facts prompted Mayor Harry L. Davis to shut down the probe, declaring it was no one’s fault. Three men, none of whom were Garrett or Frank Morgan, received the $500 Carnegie Hero Fund award for the rescue effort. Two of the recipients had rescued no one. Morgan wasn’t mentioned in official reports.

The Great Depression, which hit Morgan’s finances as hard as so many others, prompted him to go looking for evidence of his participation in the rescue. He wanted both recognition and financial compensation for the nightmares it had caused. Once again, his tenacity and hard work paid off. Victor Sincere founded a citizen’s group that gave Morgan a diamond-studded medal. He received a gold medal from the International Association of Fire Engineers as well as an honorary membership and degree from Case Western Reserve. The City of Cleveland gave him a watch and paid for his brother’s funeral in 1962.🕜

Those who made the first attempt to effect a rescue all fell unconscious from the gas. A second attempt was led by Van Duzen himself. Seeing his fellow rescuers started to collapse, he told one of his men, Martin Nelson, to get everyone out. Van Duzen fell to the floor, unconscious, injuring his hip. When those above realized the second rescue party wasn’t going to be returning, someone remembered Morgan’s new safety hood and thought it would be a good idea to get a few of them.

Few men were keen on volunteering for a third rescue attempt. Someone asked Morgan if he would go down. He agreed without hesitation, and along with Frank, Tom Clancy and Gilbert Martin Via, he took an elevator down 111 feet. He came across a door behind which he could hear pounding. Unable to open it, he smashed its glass window, retrieved a man behind, and brought him to the surface. The rescuers brought up two living men—one being Van Duzen—and four bodies. Cleveland’s mayor, waiting on the surface, congratulated Morgan.

Ten rescuers perished as did 12 tunnel diggers for a total of 22. Morgan’s heroism was virtually erased from the historical record. No newspaper this author could find mentioned his name save for one article in the African American newspaper The Monitor published in Omaha, Nebraska. The Cleveland Plain Dealer named the heads of the third rescue party as D.J. Parker and L.M. Jones. Much praise was heaped upon Van Duzen. Because of lingering gas, the effort to find twelve men who’d been buried temporarily stopped until all the gas could be vented out of the tunnel.

City Hall launched a probe into the disaster with idea of putting the blame on Vokes, Van Duzen, Johnston, and a city chemist for his failure to take a timely test for gas in the tunnel. Witnesses told a different story, pointing out that a lack of necessary equipment such as a telephone line had been the real cause. These unwanted facts prompted Mayor Harry L. Davis to shut down the probe, declaring it was no one’s fault. Three men, none of whom were Garrett or Frank Morgan, received the $500 Carnegie Hero Fund award for the rescue effort. Two of the recipients had rescued no one. Morgan wasn’t mentioned in official reports.

The Great Depression, which hit Morgan’s finances as hard as so many others, prompted him to go looking for evidence of his participation in the rescue. He wanted both recognition and financial compensation for the nightmares it had caused. Once again, his tenacity and hard work paid off. Victor Sincere founded a citizen’s group that gave Morgan a diamond-studded medal. He received a gold medal from the International Association of Fire Engineers as well as an honorary membership and degree from Case Western Reserve. The City of Cleveland gave him a watch and paid for his brother’s funeral in 1962.🕜

Ad for Garrett Morgan's Safety Hood

Chronicling America. Library of Congress

Chronicling America. Library of Congress

Garrett Morgan's gas mask patent, which he called a safety hood.

Garrett Morgan's Traffic Light Patent

Photo of Garrett Morgan bringing the first man he rescued out of the tunnel.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons