INVENTION OF THE PADDED BICYCLE SEAT

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

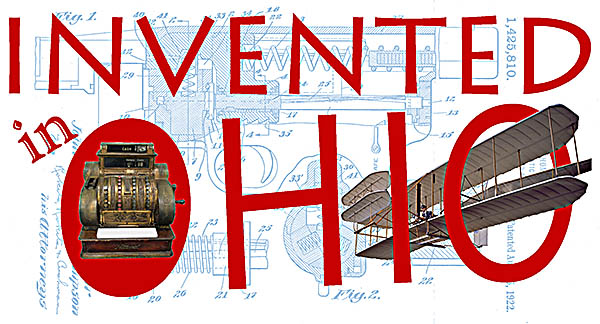

Arthur Lovett Garford. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

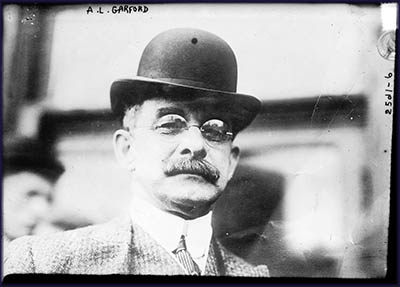

William Martin, Racing Champion, on His Ordinary (Penny-Farthing) Bicycle

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

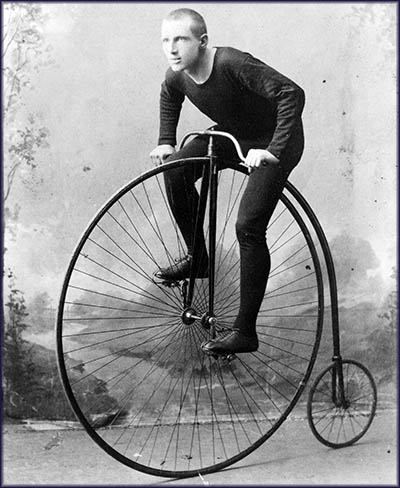

"Bicycling." L. Prang & Co., 1897.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

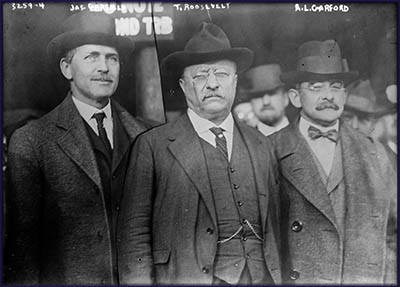

James Randolph (left), Theodore Roosevelt (Middle), and Arthur Garford (Right).

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

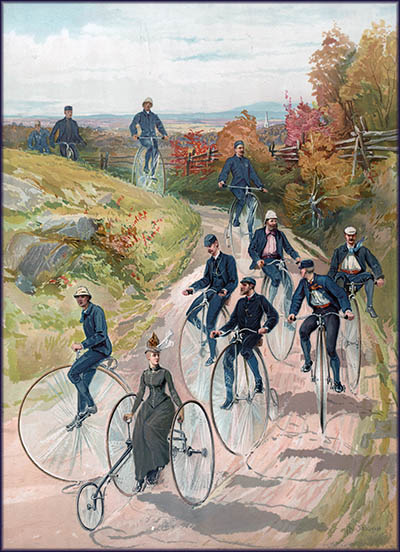

Garford Bike Seat

Lorain County History Center and The Hickories. Elyria, Ohio.

Lorain County History Center and The Hickories. Elyria, Ohio.

The earliest version of the bicycle, if you can call it that, appeared in Italy in 1418. Invented by Italian engineer Giovanni Jacopo Antonio de la Fontana, it had four wheels. In 1817, Karl Freiherr von Drais, a German aristocrat, invented what he called the dandy-horse, a device that more or less resembled a modern bicycle minus the pedals. After straddling it, a rider used his or her feet to produce motion by pushing along the ground. Made of wood, it weighed fifty pounds and, after sparking a brief fad in France and England, its use subsided.

The name “dandy-horse” never really stuck and for a time similar machines were known as velocipedes. The English word “bicycle” first appeared in print in 1868. Who invented the idea of powering the velocipede with pedals attached to the hub of the front wheel is hard to say with certainty, though it is known that in 1866 Frenchman Pierre Lallement received a patent in the United States for one. In May 1867, an ad appeared in the French periodical Le Monitor universal du soir for just such a one designed by a Parisian blacksmith named Pierre Michaux. He’d been financed by brothers Aimé, Marius and René Oliver from Lyon, who’d likely as not told Michaux what to build.

The name “dandy-horse” never really stuck and for a time similar machines were known as velocipedes. The English word “bicycle” first appeared in print in 1868. Who invented the idea of powering the velocipede with pedals attached to the hub of the front wheel is hard to say with certainty, though it is known that in 1866 Frenchman Pierre Lallement received a patent in the United States for one. In May 1867, an ad appeared in the French periodical Le Monitor universal du soir for just such a one designed by a Parisian blacksmith named Pierre Michaux. He’d been financed by brothers Aimé, Marius and René Oliver from Lyon, who’d likely as not told Michaux what to build.

Made of cast iron, the front wheel was only slightly larger than the rear one. It was so uncomfortable to ride that it became known as the boneshaker. Having no brakes, a rider stopped it by reversing the pedal motion. Soon enough, someone thought to build bikes out of hollow metal tubes to make them lighter. Next in the evolution of the bicycle came the ordinary, or penny-farthing, so called because a farthing was worth one-fourth of a penny, a metaphor representing the fact that the machine’s front wheel was nearly four times larger than the rear. This design was used in 1870 by English bicycle racer James Moore because it gave him a serious speed advantage. He also had the seat moved above the front wheel.

These monster-sized bicycles were dangerous to ride. Falling off one could result in serious injury or death. Those who flipped over the front wheel and went flying through the air took a “header.” Some thought a tricycle would be a safer alternative, with most having chain connecting from the pedals to the front wheel. This innovated likely inspired what became known as a safety bike that had front and back tires of the same size and was powered by gears and a chain to give it the same speed as an ordinary.

These monster-sized bicycles were dangerous to ride. Falling off one could result in serious injury or death. Those who flipped over the front wheel and went flying through the air took a “header.” Some thought a tricycle would be a safer alternative, with most having chain connecting from the pedals to the front wheel. This innovated likely inspired what became known as a safety bike that had front and back tires of the same size and was powered by gears and a chain to give it the same speed as an ordinary.

Ever since the first boneshaker was introduced, much of the world had embraced bicycling, and the United States was no exception. Yet by the beginning of the 1890s, no one had thought to introduce a padded seat. The man who came up with the idea, Arthur Lovett Garford, was a bank clerk. Born on a farm near Elyria, Ohio, on August 4, 1858, he graduated from Elyria High School in 1875. At the age of 19, he took the position of cashier at the fine china importer Rice & Burnett in Cleveland where he worked until 1880. Returning to Elyria, he became a bookkeeper at the Savings Deposit Bank. He rose to the rank of a cashier, a position probably obtained in part because in 1881 he’d married the bank president’s daughter, Mary Louise Nelson.

While at the bank, Garford became a keen bicyclist, but he disliked the hard wooden seats. In 1889, he replaced his with one of his own design. Covered in leather, it was cushioned by a spring and could be tilted so a person could adjust it for maximum comfort. He made a few for his friends as well, and it proved to be so popular it was quickly adapted by bicyclists in Elyria. Realizing he had a winning product, Garford decided to sell his idea, but no one wanted to pay a fair price for it. Undaunted, he contracted a manufacturer to make them. He filed for his patent on August 10, 1889. William J. Edwards, who’d filed a similar patent on December 14, 1889, appealed that decision, but Garford prevailed. His patent was granted on July 8, 1890.

While at the bank, Garford became a keen bicyclist, but he disliked the hard wooden seats. In 1889, he replaced his with one of his own design. Covered in leather, it was cushioned by a spring and could be tilted so a person could adjust it for maximum comfort. He made a few for his friends as well, and it proved to be so popular it was quickly adapted by bicyclists in Elyria. Realizing he had a winning product, Garford decided to sell his idea, but no one wanted to pay a fair price for it. Undaunted, he contracted a manufacturer to make them. He filed for his patent on August 10, 1889. William J. Edwards, who’d filed a similar patent on December 14, 1889, appealed that decision, but Garford prevailed. His patent was granted on July 8, 1890.

Garford’s patent makes no mention of padding, though the version seen by the author at Garford's home in Elyria definitely had it. Nearly all the obituaries and biographical sketches published during Garford’s lifetime emphasize the padded seat was for comfort. An account in the second volume of the 1916 book A Standard History of Lorain County states that before switching to the safety bike, Garford rode an ordinary from which he fell repeatedly, one being serious. The reason for his new bike seat wasn’t for a more comfortable ride, but rather a safer one.

The bike saddles of the day had a habit of twisting, knocking a rider off balance and sometimes off the bike itself. Garford designed his saddle specifically so it would never twist. It could be adjusted to fit the rider’s needs. A spring made the ride safer because it cushioned jolts from running over, say, a pothole, keeping the rider firmly on the seat rather than being bounced upward.

The bike saddles of the day had a habit of twisting, knocking a rider off balance and sometimes off the bike itself. Garford designed his saddle specifically so it would never twist. It could be adjusted to fit the rider’s needs. A spring made the ride safer because it cushioned jolts from running over, say, a pothole, keeping the rider firmly on the seat rather than being bounced upward.

Garford couldn’t have patented his new invention at a better time. In the 1890s there was a bicycle craze in the United States and his seat sold in the millions, making him a very wealthy man. He formed the American Saddle Company that absorbed other bicycle saddle manufacturers and became the American Bicycle Company with him as its treasurer. By 1900, the company was worth $5 million He left it in 1901 to start another company, a pattern he repeated until his death on January 23, 1933.

Garford also dabbled in politics. In 1912 Theodore Roosevelt, having failed to secure the Republican nomination for president, started the Progressive Party, known better to history as the Bull-Moose Party. Garford joined and ran as the party’s candidate for Ohio governor and, two years later, for the U.S. Senate. He lost both times. A grateful Roosevelt gave the head of a moose he’d killed during a hunt to Garford as a reward. It hangs on the wall in Garford’s house in Elyria—the Hickories—which is now a museum.🕜

Garford also dabbled in politics. In 1912 Theodore Roosevelt, having failed to secure the Republican nomination for president, started the Progressive Party, known better to history as the Bull-Moose Party. Garford joined and ran as the party’s candidate for Ohio governor and, two years later, for the U.S. Senate. He lost both times. A grateful Roosevelt gave the head of a moose he’d killed during a hunt to Garford as a reward. It hangs on the wall in Garford’s house in Elyria—the Hickories—which is now a museum.🕜