INVENTION OF THE RESEALABLE PAINT CAN

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

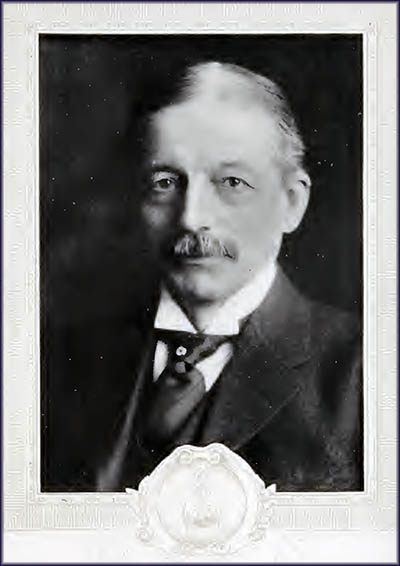

Henry Alden Sherwin. From What Fifty Years Have Wrought.

Digitized by Google

Digitized by Google

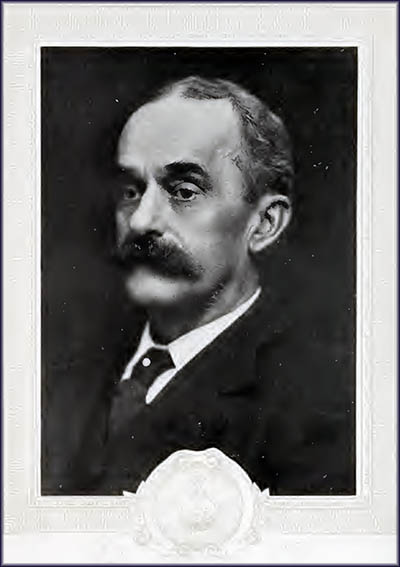

Edward Porter Williams. From What Fifty Years Have Wrought.

Digitized by Google

Digitized by Google

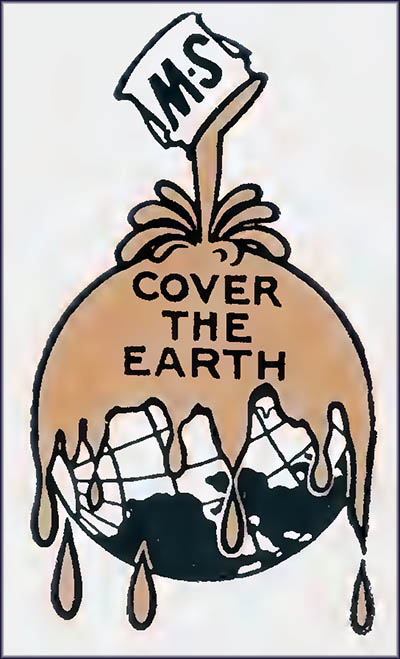

Sherwin Williams famous paint logo. From What Fifty Years Have Wrought.

Digitized by Google

Digitized by Google

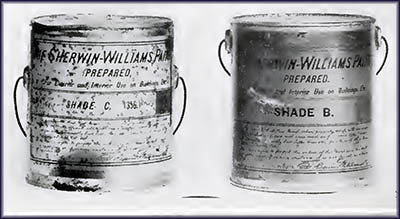

Early Sherwin-Williams paint cans. From What Fifty Years Have Wrought.

Digitized by Google

Digitized by Google

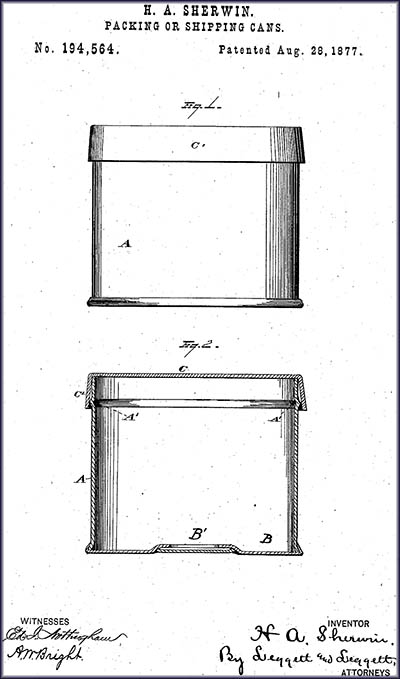

Henry Sherwin's Resealable Paint Can Patent

If you wanted to paint your house inside and out in 1866, you couldn’t go down to the local hardware or general store and buy it in a can. Premixed paint hadn’t yet been invented, nor had a reusable container in which to store it. Most house painters in this era were professionals who needed to buy a variety of supplies for a job. Brushes and vessels for mixing the paint were needed, as was turpentine, linseed oil, white lead, a marble slab and a pestle to grind the raw materials used for coloring into a fine powder. White lead was used for the base coloring, and a mixture of this and linseed oil was made into paste, then diluted by turpentine or mineral spirits. An exceptionally bright white could be made using nut oil.

On July 16, 1867, a patent was granted to D.R. Averill for a premixed metallic-based paint he’d developed for his business, the Averill Chemical Paint Company, which was located in Centerville, New York. Averill, who was originally from Newberg, Ohio, noted in his patent application that one of the drawbacks of the oil-based paints of the day was that painters had to purchase all sort of ingredients to just create their paint, each item being in its own package. If not mixed just right, the paint couldn’t be used. When mixed correctly, it had to be used quickly else the mineral portion used for color would settle to the bottom and no amount of stirring would get it to mix back in. You’d have to separate it out and regrind it. After a time, the paint also became “fatty,” making it useless.

On July 16, 1867, a patent was granted to D.R. Averill for a premixed metallic-based paint he’d developed for his business, the Averill Chemical Paint Company, which was located in Centerville, New York. Averill, who was originally from Newberg, Ohio, noted in his patent application that one of the drawbacks of the oil-based paints of the day was that painters had to purchase all sort of ingredients to just create their paint, each item being in its own package. If not mixed just right, the paint couldn’t be used. When mixed correctly, it had to be used quickly else the mineral portion used for color would settle to the bottom and no amount of stirring would get it to mix back in. You’d have to separate it out and regrind it. After a time, the paint also became “fatty,” making it useless.

Averill, proud of his invention, invited others to his factory to see how it was made. One visitor, Henry Alden Sherwin, wasn’t impressed. Born in Baltimore, Vermont, on September 27, 1842, Sherwin began his business career at the age of thirteen. In 1860 he moved to Cleveland to worked as bookkeeper at Freeman & Kellogg dry goods business. When that folded, he joined wholesale grocer Sprague & Co., which he found not to his liking. Departing from this, in 1866 he spent his life’s savings of $2,000 to form a partnership with Truman Dunham and G.O. Griswold.

Truman Dunham & Co. was a wholesaler and retailer of oils, paints, varnishes, and similar products. Sherwin knew absolutely nothing about this business, so he decided to learn everything he could. He later recalled, “I frequently put on old clothes and worked like a porter. I opened packages and examined their contents, found what they were for and how used, compared costs, and evenings studied all the books and catalogs I could find which in any way referred to these materials.” In 1869 the company erected a linseed oil factory. Sherwin wanted to expand the paint portion of the business. His partners balked, so he left with it.

Truman Dunham & Co. was a wholesaler and retailer of oils, paints, varnishes, and similar products. Sherwin knew absolutely nothing about this business, so he decided to learn everything he could. He later recalled, “I frequently put on old clothes and worked like a porter. I opened packages and examined their contents, found what they were for and how used, compared costs, and evenings studied all the books and catalogs I could find which in any way referred to these materials.” In 1869 the company erected a linseed oil factory. Sherwin wanted to expand the paint portion of the business. His partners balked, so he left with it.

To continue operations, he needed new partners. In January 1870 he formed Sherwin-Williams with Edward P. Williams and Alanson T. Osborne, who would serve as the firm’s head accountant. Williams, born on May 10, 1843, in Cleveland, invested $15,000 in the venture. He focused on the business side of the company and developed its sales staff. Born on April 11, 1845, in Rensselaerville, New York, Osborn came to Cleveland in 1862 and went to work for R.P. Meyers, which made tin plates, tinners’ supplies, and stoves. When he became a partner in the firm, it was renamed Myers, Osborn & Company. This he left in 1868. He didn’t stay at Sherwin-Williams all that long, either. He departed in 1882.

Sherwin patented a new type of metal can used for packing and shipping in 1877. This resealable can wasn’t like the modern one we know today, but it was nonetheless quite an advancement. It had a flanged lid soldered on for shipping. The solder was soft enough that one could use a knife to cut through it, leaving the flanged lid undamaged so it could be used to reseal the can. In his patent application, Sherwin made it clear his can was perfect to hold paint. This invention would make Sherwin-Williams’s move into premixed paint a few years later far easier because buyers didn’t have to use it up right after opening the can lest it go bad. Sherwin-Williams’ Cleveland factory, built in 1872, produced its own cans, labels, paints, varnishes, and related products. Sherwin wanted to create a ready-mixed paint far superior to Averill’s.

Sherwin patented a new type of metal can used for packing and shipping in 1877. This resealable can wasn’t like the modern one we know today, but it was nonetheless quite an advancement. It had a flanged lid soldered on for shipping. The solder was soft enough that one could use a knife to cut through it, leaving the flanged lid undamaged so it could be used to reseal the can. In his patent application, Sherwin made it clear his can was perfect to hold paint. This invention would make Sherwin-Williams’s move into premixed paint a few years later far easier because buyers didn’t have to use it up right after opening the can lest it go bad. Sherwin-Williams’ Cleveland factory, built in 1872, produced its own cans, labels, paints, varnishes, and related products. Sherwin wanted to create a ready-mixed paint far superior to Averill’s.

A perfectionist who hated dirt and clutter, he thought little of Averill’s formula. Runny and not very opaque, it was made with linseed oil, zinc oxide, and other ingredients. Averill sued anyone using zinc-oxide in his paint, a plan that backfired. In 1881, his patent was rescinded as being too broad. Sherwin was delighted that other companies had based their premixed paint on Averill’s formula because neither it nor theirs sold well, allowing his company to get into the premixed paint market several years later with little competition.

Sherwin felt one of the biggest problems with Averill’s paint was that it used it low quality ingredients. In the mid-1870s, he and a company engineer, Henry Coventry, created a far better stone mill to grind ingredients, which the company used for the next fifty years with few modifications. Sherwin-Williams’ first ready-mixed exterior paint appeared in 1875 as a blue enamel. A line of interior paints, Osborn Family Paint, appeared in 1878. Sales weren’t stellar because the poor-quality premixed paints already on the market had a bad reputation. In 1880, a new line under the Sherwin-Williams name came out with a warranty guaranteeing it wouldn’t crack, peel, and would last longer than anything else on the market. The company launched a nationwide advertising campaign that yielded much profit and allowed it to expand.

Sherwin felt one of the biggest problems with Averill’s paint was that it used it low quality ingredients. In the mid-1870s, he and a company engineer, Henry Coventry, created a far better stone mill to grind ingredients, which the company used for the next fifty years with few modifications. Sherwin-Williams’ first ready-mixed exterior paint appeared in 1875 as a blue enamel. A line of interior paints, Osborn Family Paint, appeared in 1878. Sales weren’t stellar because the poor-quality premixed paints already on the market had a bad reputation. In 1880, a new line under the Sherwin-Williams name came out with a warranty guaranteeing it wouldn’t crack, peel, and would last longer than anything else on the market. The company launched a nationwide advertising campaign that yielded much profit and allowed it to expand.

The prime ingredient of Sherwin-Williams’ paints was lead despite the fact it was well known to be a dangerous poison. The company used it anyway because professional painters demanded it. They, too, knew it was deadly and just didn’t care, possibly because they assigned the hazardous work of grinding it up into a powder or sanding old lead paint down to their apprentices. Professional painters got quite upset if the paint they purchased was “adulterated” with a safer alternative to lead such as titanium dioxide. They demanded that legislators force honest labeling on paint cans. Several states passed such laws, though a federal one never materialized. The Sherwin-Williams logo had “Old Dutch Process” as part of its logo because it was a euphemism aimed at professional painters guaranteeing it had lead in it.🕜