INVENTION OF THE THOMPSON SUBMACHINE GUN

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

John Taliaferro Thompson, 1915.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

American soldiers with a Gating gun in the Philippines. Photo by George C. Dotter, 1899.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Thomas Fortune Ryan

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

George Harvey. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Solider with Thompson Submachine Gun

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

The Thompson submachine gun was a commercial failure. Were it not for the timely arrival of World War II, the company that produced this weapon, Auto-Ordnance, would have likely gone out of business. Its first gun went on sale in 1921 and by 1929 the company was $2,200,000 in debt. Why? When formed, the company planned to sell its guns to the world’s militaries. The trouble was, World War I had bankrupted nearly every participant in the conflict except for the United States, forcing them to slash their military budgets. The U.S. government had the funds to buy new weapon but decided to severely downsize the military instead. This forced Auto-Ordnance to sell to the civilian market, but the gun was too expensive for sales to be equal to a healthy military contract.

Some Thompson submachine guns were sold to police departments, but the numbers purchased weren’t spectacular. The New York Police Department, for example, bought a grand total of 10 for use by the riot police and to deal with car thieves. Two officers armed with these weapons could unleash 1,500 rounds per minute. The New York Herald gleefully reported it could “be made to spray like a hose, and this new method of massing fire enables even the inexperienced marksman to shoot with the effect of a Bill Cody. The spraying is done in the case of moving targets, and the action is as easy as that of a fireman spraying water on a blaze.”

Some Thompson submachine guns were sold to police departments, but the numbers purchased weren’t spectacular. The New York Police Department, for example, bought a grand total of 10 for use by the riot police and to deal with car thieves. Two officers armed with these weapons could unleash 1,500 rounds per minute. The New York Herald gleefully reported it could “be made to spray like a hose, and this new method of massing fire enables even the inexperienced marksman to shoot with the effect of a Bill Cody. The spraying is done in the case of moving targets, and the action is as easy as that of a fireman spraying water on a blaze.”

General William Rufus Shafter in Cuba During the Spanish-American War

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

M1911 Pistol

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

M1903 Springfield Rifle

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

Thompson Submachine Gun with 100 Round Drum

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

Soldiers Training with the Thompson Submachine Gun at Daniel Field, Georgia

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

This is a Krag-Jørgensen, the gun upon which the United States' first bolt-action rifle was based.

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

The U.S. Armory in Springfield, Massachusetts

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Thompson Machine Guns were included with the package of weapons sent to Britain as part of Lend-Lease in the days before the U.S. entered World War II.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Soldier showing how the Thompson submachine gun could complement U.S. armor. Photo by Alfred T. Palmer. United States. Office of War Information.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

The gun’s inventor, John Taliaferro Thompson, had in mind an entirely different purpose for his weapon. He’d envisioned it as “trench broom” for use in World War I. It would give an individual soldier the firepower necessary to counter fixed machine guns and to clear out a trench in short order. Thompson knew much about guns. Born in Newport, Kentucky, on December 31, 1860, he came from a military family. He attended Indiana University, then went to West Point from which he graduated in 1882. In 1884 he took the torpedo course at the Engineer School at Willets Point, New York. He updated his military education in 1890 at the United States Artillery School at Fort Monroe in Virginia.

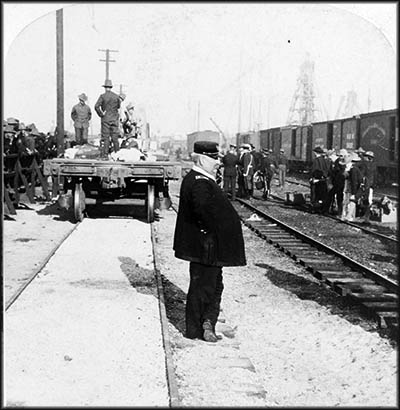

A career ordnance officer, when the Spanish-American War broke out on April 21, 1898, he was put under the command of Major General William Rufus Shafter, whose Fifth Corps was tasked with invading Cuba. Thompson went to Tampa Bay, Florida, to oversee the shipment of all the arms and ammunition the expeditionary force heading to Cuba needed. During his time in Tampa Bay, nearly 18,000 tons of ordnance went to Cuba on time and without any issues. A young lieutenant named John Henry Parker pointed out to Thompson that there were also fifteen Gatling guns at his deposal. Although Thompson had no orders to ship those, he saw their value and sent them anyway. Were it not for those guns being strategically placed, the Americans might never have taken San Juan Hill where future president Theodore Roosevelt led his famous charge.

A career ordnance officer, when the Spanish-American War broke out on April 21, 1898, he was put under the command of Major General William Rufus Shafter, whose Fifth Corps was tasked with invading Cuba. Thompson went to Tampa Bay, Florida, to oversee the shipment of all the arms and ammunition the expeditionary force heading to Cuba needed. During his time in Tampa Bay, nearly 18,000 tons of ordnance went to Cuba on time and without any issues. A young lieutenant named John Henry Parker pointed out to Thompson that there were also fifteen Gatling guns at his deposal. Although Thompson had no orders to ship those, he saw their value and sent them anyway. Were it not for those guns being strategically placed, the Americans might never have taken San Juan Hill where future president Theodore Roosevelt led his famous charge.

After the war, Thompson debriefed men who had served in Cuba to determine why the American troops had had such a devil of a time against the Spaniards. He helped determine the culprit was the rifle the American soldiers were issued. The U.S. Army had given its infantry the Norwegian-designed Krag-Jørgensen, a gun first introduced in 1888 with a five-round magazine that had to be loaded one cartridge at time. The Spaniards, in contrast, used the far superior 1893 Mauser. The Army assigned Thompson to design a replacement for the Krag-Jørgensen and sent him to the Springfield Armory for that purpose. He based the replacement rifle on the 1893 Mauser, which evolved into the Springfield M1903, a gun that had the added advantage of using the new .30-’06 smokeless powder cartridge.

Next Thompson was tasked with replacing the Colt M1892 revolver because its .38 caliber round lack stopping power. The U.S. Army discovered this the hard way during its suppression of the Philippine Insurrection, a conflict sparked after the United States bought the Philippines from Spain at the conclusion of the Spanish-American War and made it a colony. To determine the best caliber for the replacement pistol, in 1904 Thompson and army surgeon Major Louis La Garde of the Medical Corps headed to the Nelson Morris & Company’s stockyards in Chicago where they shot a dozen or so cattle using different calibers of ammunition. At some point they also fired at human cadavers. From these tests they decided the best caliber would be .45. Next Thompson tested a variety of pistols. John Moses Browning’s new Colt semiautomatic pistol was chosen and issued as the M1911.

Next Thompson was tasked with replacing the Colt M1892 revolver because its .38 caliber round lack stopping power. The U.S. Army discovered this the hard way during its suppression of the Philippine Insurrection, a conflict sparked after the United States bought the Philippines from Spain at the conclusion of the Spanish-American War and made it a colony. To determine the best caliber for the replacement pistol, in 1904 Thompson and army surgeon Major Louis La Garde of the Medical Corps headed to the Nelson Morris & Company’s stockyards in Chicago where they shot a dozen or so cattle using different calibers of ammunition. At some point they also fired at human cadavers. From these tests they decided the best caliber would be .45. Next Thompson tested a variety of pistols. John Moses Browning’s new Colt semiautomatic pistol was chosen and issued as the M1911.

Thompson retired in 1914 after 32 years in the Army. He went to work for the Remington Arms Company for which he designed and oversaw the construction of the company’s Eddystone plant near Chester, Pennsylvania. According to Bill Yenne’s book Tommy Gun: How General Thompson’s Submachine Gun Wrote History, the factory produced the “3-Line Mosin-Nagant rifle for the Russians and the Enfield rifle for the British.” It was while working here and reading about the brutal trench warfare in Europe that Thompson conceived of the idea for his “trench broom,” a lightweight machine gun sized for a soldier to carry just like a rifle. For such a weapon to be made, the parts of a standard machine gun needed to be miniaturized and simplified. One issue some machines guns had was that their bolt opened prematurely, resulting in the weapon firing on its own. This needed to be avoided.

John Blish, who served for many years in the U.S. Navy, noticed that the breech block of rear-loading heavy guns tended to unscrew when less powerful loads of ammunition were fired. He thought the solution was to make the breech block out of one type of metal and the bolt out of another because being different, they would “adhere” together under pressure, which would slow the bolt and thus prevent it from opening when it ought not to. Blish called this phenomenon the Blish principle and patented a lock for small arms based on it. An excited Thompson decided this was just what he needed. In reality Blish got it all wrong. His new breech block worked because it had more mass, not some magical fusion of metals.

John Blish, who served for many years in the U.S. Navy, noticed that the breech block of rear-loading heavy guns tended to unscrew when less powerful loads of ammunition were fired. He thought the solution was to make the breech block out of one type of metal and the bolt out of another because being different, they would “adhere” together under pressure, which would slow the bolt and thus prevent it from opening when it ought not to. Blish called this phenomenon the Blish principle and patented a lock for small arms based on it. An excited Thompson decided this was just what he needed. In reality Blish got it all wrong. His new breech block worked because it had more mass, not some magical fusion of metals.

While still working at Remington, Thompson decided to start his own company to produce his new gun. He approached Blish and offered him stock options in the new concern in exchange for the license to use the Blish lock. To this Blish agreed. Next Thompson approached his former assistant from the Ordnance Department, Theodore Eickhoff, to serve as his chief engineer. He secured financing from Wallstreet financier Thomas Fortune Ryan. Ryan didn’t need the money but agreed to invest so long as he had controlling interest. To this Thompson concurred, and thus was the Auto-Ordnance Corporation was founded.

Eickhoff and Thompson began work at Thompson’s house in Chester, Pennsylvania, to design the new gun. There are two ways to power a machine gun. The first is to siphon off some of the gas produced by the explosion of cartridge to automate the loading and firing of the next round. The second is to power it using the gun’s recoil. Thompson’s gun would use this latter type of power. His home workshop lacked the tools needed to build a proper prototype, so Eickhoff moved to Cleveland where he was given space in the basement at a machine tool factory ran by Ambrose Swasey and Worcester Reed Warner. The prototype Eickhoff made was designed like a standard rifle. It exploded during the testing caused by its .30-’06 cartridge. Without lubrication, it failed, and greasing ammunition is undesirable on the battlefield because it attracts dirt. Eickhoff suggested they switch to the smaller yet quite powerful rimless .45 caliber round developed for the M1911 pistol.

Eickhoff and Thompson began work at Thompson’s house in Chester, Pennsylvania, to design the new gun. There are two ways to power a machine gun. The first is to siphon off some of the gas produced by the explosion of cartridge to automate the loading and firing of the next round. The second is to power it using the gun’s recoil. Thompson’s gun would use this latter type of power. His home workshop lacked the tools needed to build a proper prototype, so Eickhoff moved to Cleveland where he was given space in the basement at a machine tool factory ran by Ambrose Swasey and Worcester Reed Warner. The prototype Eickhoff made was designed like a standard rifle. It exploded during the testing caused by its .30-’06 cartridge. Without lubrication, it failed, and greasing ammunition is undesirable on the battlefield because it attracts dirt. Eickhoff suggested they switch to the smaller yet quite powerful rimless .45 caliber round developed for the M1911 pistol.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Thompson returned to the Army. He was made Chief, Small Arms Division at the Ordnance Office and given the brevet rank of brigadier general. His new duty took him to Washington, D.C. where he met and was impressed by Oscar Payne, an engineer who worked for a patent attorney firm. Payne, Thompson and Eickhoff met in Washington, D.C. to discuss the next phase of the new gun’s development. Payne suggested rather than model it on a rifle, it ought to be more like a pistol.

Thompson put Payne on Auto-Ordnance’s payroll and sent him back with Eickhoff to Cleveland. There the two men reworked the gun. Payne found a belt-fed mechanism didn’t work well, so he temporarily changed it to a metal magazine. This functioned so well, he abandoned the belt-fed idea. The new prototype was dubbed the Annihilator. In the summer of 1918, Payne and Eickhoff took it into a woods near Cleveland one afternoon and found it worked near perfectly. At this stage someone thought to called it a submachine gun, a name that stuck. Its development had cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Thompson put Payne on Auto-Ordnance’s payroll and sent him back with Eickhoff to Cleveland. There the two men reworked the gun. Payne found a belt-fed mechanism didn’t work well, so he temporarily changed it to a metal magazine. This functioned so well, he abandoned the belt-fed idea. The new prototype was dubbed the Annihilator. In the summer of 1918, Payne and Eickhoff took it into a woods near Cleveland one afternoon and found it worked near perfectly. At this stage someone thought to called it a submachine gun, a name that stuck. Its development had cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Although the name “submachine gun” was new, the concept wasn’t. During World War I the Germans had developed a 9mm Bergmann MP 18/1 machine pistol for use in the trenches. The British, in contrast, wanted no such weapon in the infantryman’s hands for fear he would fire off all the rounds at once. Auto-Ordnance decided to name its new weapon the Thompson submachine gun. When the nickname “Tommy gun” came into use, the company trademarked it. Colt Patent Fire-Arms Manufacturing Company made the initial stock of 15,000 guns. Empty, the gun weighed 10 pounds four ounces. Its weight increased depending on the size of the magazine used, which came in three sizes: 20, 50, and 100. The 100-round magazine added three pounds two ounces to the gun’s weight.

Although the gun did have a single-shot feature, its key selling point was how fast it could fire rounds on full automatic. One problem with a gun with a such a high rate of fire as this is that its muzzle tends to climb. The Thompson’s accuracy is poor anyway, and this made it worse. To remedy this, a compensator placed at the end of the barrel was needed. Colonel Richard M. Cutts and his son invented one in 1926 that pushed the barrel downwards by venting gas upwards. The Lyman Corporation began selling it the next year.

In June 1921, a labor strike forced the Cosmopolitan Shipping Company to hire a strikebreaking engineering crew consisting of “cocky” Irishmen for its cargo ship East Side, which was bound for Dublin, Ireland, was docked at Pier 2 in Hoboken, New Jersey. One Sunday morning these engineers brought on board from launches 13 large sacks that they hauled up the ship’s side and put on deck. On Monday morning the sacks started disappearing. Fearing the engineering crew consisted of union plants who’d brought a bomb on board, two crewmen—William McNarney and Charles Mason—decided to take a closer look at one of these sacks. Cutting one open, they saw a gun butt. Colonel George Bartlett, Cosmopolitan’s general manager, was informed.

Although the gun did have a single-shot feature, its key selling point was how fast it could fire rounds on full automatic. One problem with a gun with a such a high rate of fire as this is that its muzzle tends to climb. The Thompson’s accuracy is poor anyway, and this made it worse. To remedy this, a compensator placed at the end of the barrel was needed. Colonel Richard M. Cutts and his son invented one in 1926 that pushed the barrel downwards by venting gas upwards. The Lyman Corporation began selling it the next year.

In June 1921, a labor strike forced the Cosmopolitan Shipping Company to hire a strikebreaking engineering crew consisting of “cocky” Irishmen for its cargo ship East Side, which was bound for Dublin, Ireland, was docked at Pier 2 in Hoboken, New Jersey. One Sunday morning these engineers brought on board from launches 13 large sacks that they hauled up the ship’s side and put on deck. On Monday morning the sacks started disappearing. Fearing the engineering crew consisted of union plants who’d brought a bomb on board, two crewmen—William McNarney and Charles Mason—decided to take a closer look at one of these sacks. Cutting one open, they saw a gun butt. Colonel George Bartlett, Cosmopolitan’s general manager, was informed.

He boarded to tell the engineering crew they were dismissed. He promised to pay them for the time they’d put in, but none of them collected their earnings because they’d have had to give their names. On Monday night, a launch came alongside the East Side and men tried to board, but the night watchman threatened to shoot them if they did. He called his fellow crewmen for help to repel these boarders. The men in the launch claimed the marine superintendent had authorized them to come on board. The watchman left to call to ask this official if there were any truth to that. There was not. By the time the watchman returned, the launch had gone.

On June 15, 1921, U.S. Customs agents came on board to find what they believed was a cache of arms purchased by Sinn Féin, an Irish independence political party that planned to give the guns to the Irish Republican Army. The IRA was a designated enemy of American ally Great Britain. Existing U.S. neutrality laws made it illegal to sell the weapons to this force. The sacks were well-hidden, and it took custom agents four searches before they found them stashed in a coal bunker. They seized 600 Thompson submachine guns worth $150,000.

An investigation by authorities determined that the guns had been sold to Frank Williams. When asked, he claimed they’d been stolen from him on June 11. He refused to explain why he hadn’t reported the theft. He claimed to have the invoices and to have sold the guns legally to James O’Brien from Dublin. Williams asked the U.S. government for his guns back because they were his property. They’d supposedly been taken to a warehouse in Hoboken, but when the driver who delivered them returned, he had no receipt. It turned out Frank Williams was an alias for Lawrence de Lacy, aka Lawrence Pierce, aka Frank Kernan. His brother was Edward de Lacy, who used the alias Fred Williams.

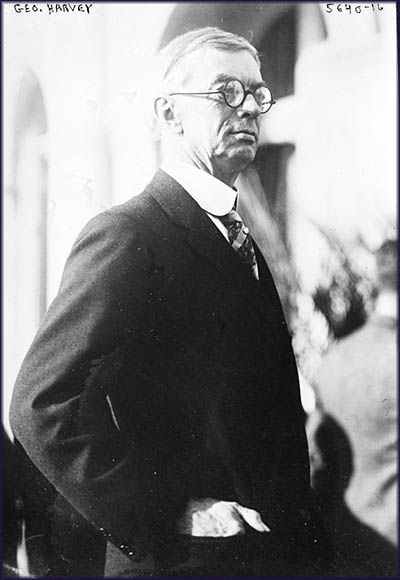

General Thompson, the sole dealer of gun sales, said he had no records of selling guns to Williams or of a sale of 600 guns at once. What he hadn’t realized was his son , who served as Auto-Ordnance’s vice president, had facilitated their sale. A year after the guns were seized, Marcellus and seven others were charged for violating American neutrality laws. When General Thompson and Marcellus’s father-in-law—George Brinton McClellan Harvey, the ambassador to the United Kingdom—found out, they were horrified.

Fortunately for the seven indicted, prosecutor incompetence and a changing political situation between Britain and Ireland resulted in the case being dropped. It’s likely Marcellus and his co-defendants knew exactly where those guns were going. The scandal was too much for Marcellus’s wife, Dorothy. She divorced him over it.

Low sales forced Thompson to leave Auto-Ordnance in 1928. Congress retroactively promoted him to the rank of brigadier general two years later. By 1939 Auto-Ordnance was on the verge of going out of business. Then World War II broke out and demand for a portable machine gun rose almost overnight. The French ordered 3,000. The British bought as many as they could get. Their commandos loved them. Just after John Thompson’s death on June 21, 1940, the U.S. Army, which had up to that point bought just 400 of Auto-Ordnance’s guns, put in the sort of order Thompson had hoped for in the beginning: 20,000. In 1942 the number ordered surpassed 300,000.🕜

On June 15, 1921, U.S. Customs agents came on board to find what they believed was a cache of arms purchased by Sinn Féin, an Irish independence political party that planned to give the guns to the Irish Republican Army. The IRA was a designated enemy of American ally Great Britain. Existing U.S. neutrality laws made it illegal to sell the weapons to this force. The sacks were well-hidden, and it took custom agents four searches before they found them stashed in a coal bunker. They seized 600 Thompson submachine guns worth $150,000.

An investigation by authorities determined that the guns had been sold to Frank Williams. When asked, he claimed they’d been stolen from him on June 11. He refused to explain why he hadn’t reported the theft. He claimed to have the invoices and to have sold the guns legally to James O’Brien from Dublin. Williams asked the U.S. government for his guns back because they were his property. They’d supposedly been taken to a warehouse in Hoboken, but when the driver who delivered them returned, he had no receipt. It turned out Frank Williams was an alias for Lawrence de Lacy, aka Lawrence Pierce, aka Frank Kernan. His brother was Edward de Lacy, who used the alias Fred Williams.

General Thompson, the sole dealer of gun sales, said he had no records of selling guns to Williams or of a sale of 600 guns at once. What he hadn’t realized was his son , who served as Auto-Ordnance’s vice president, had facilitated their sale. A year after the guns were seized, Marcellus and seven others were charged for violating American neutrality laws. When General Thompson and Marcellus’s father-in-law—George Brinton McClellan Harvey, the ambassador to the United Kingdom—found out, they were horrified.

Fortunately for the seven indicted, prosecutor incompetence and a changing political situation between Britain and Ireland resulted in the case being dropped. It’s likely Marcellus and his co-defendants knew exactly where those guns were going. The scandal was too much for Marcellus’s wife, Dorothy. She divorced him over it.

Low sales forced Thompson to leave Auto-Ordnance in 1928. Congress retroactively promoted him to the rank of brigadier general two years later. By 1939 Auto-Ordnance was on the verge of going out of business. Then World War II broke out and demand for a portable machine gun rose almost overnight. The French ordered 3,000. The British bought as many as they could get. Their commandos loved them. Just after John Thompson’s death on June 21, 1940, the U.S. Army, which had up to that point bought just 400 of Auto-Ordnance’s guns, put in the sort of order Thompson had hoped for in the beginning: 20,000. In 1942 the number ordered surpassed 300,000.🕜