Maltz Museum of Jewish History

While not much to look at from the outside, the museum’ s interior is quite impressive.

The above photos are from

the “Israel: Then & Now” exhibit.

the “Israel: Then & Now” exhibit.

Entrance to the “An

American Story” exhibit.

American Story” exhibit.

The bland, rectangular exterior of the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage is deceptive: it contains a well-designed and sometimes stunning interior. My traveling companions and I expected it would take about an hour to go through, yet we emerged two and half hours later and could’ve gone longer. The first thing one sees upon entering is a roomy lobby that connects three different exhibits, two permanent, one temporary.

Of these we chose to start with “Israel: Then & Now,” which gives an overview of the history of modern Israel. The State of Israel traces its origins to the rise of Zionism, the desire to create an independent Jewish state in Palestine as a way to protect Jews from persecution. Popularized and promoted by Austrian journalist Theodor Herzl in the nineteenth century, it became a real possibility on November 2, 1917, when British foreign secretary Arthur James Balfour wrote a letter to Lord Rothschild (Lionel Walter) stating his government’s intention of supporting a Jewish state in Palestine so long as it preserved the civil and religious rights of those already living there. Balfour wanted a solid ally in that region of the world and thought a Jewish state would be just the thing.

But times changed and so did British policy. As caretakers of Palestine, the British decided to throttle back the emigration of Jews into it in an effort to placate the Arab population, who rejected the idea of having two states. In 1947 British colonial authorities in Palestine forcibly stopped 4,500 Jewish refugees from disembarking from the SS Exodus, a ship that had sailed from France. For the British it was a public relations disaster. It helped turn world opinion towards supporting a Jewish state in Palestine, and when one was declared on May 14, 1948, the United States and Soviet Union immediately recognized it.

Of these we chose to start with “Israel: Then & Now,” which gives an overview of the history of modern Israel. The State of Israel traces its origins to the rise of Zionism, the desire to create an independent Jewish state in Palestine as a way to protect Jews from persecution. Popularized and promoted by Austrian journalist Theodor Herzl in the nineteenth century, it became a real possibility on November 2, 1917, when British foreign secretary Arthur James Balfour wrote a letter to Lord Rothschild (Lionel Walter) stating his government’s intention of supporting a Jewish state in Palestine so long as it preserved the civil and religious rights of those already living there. Balfour wanted a solid ally in that region of the world and thought a Jewish state would be just the thing.

But times changed and so did British policy. As caretakers of Palestine, the British decided to throttle back the emigration of Jews into it in an effort to placate the Arab population, who rejected the idea of having two states. In 1947 British colonial authorities in Palestine forcibly stopped 4,500 Jewish refugees from disembarking from the SS Exodus, a ship that had sailed from France. For the British it was a public relations disaster. It helped turn world opinion towards supporting a Jewish state in Palestine, and when one was declared on May 14, 1948, the United States and Soviet Union immediately recognized it.

While a technical and stylist marvel packed full of information, “Israel: Then & Now” has a major flaw: it presents an Israel-centric version of events that whitewashes the negative effect the creation of this nation-state had has on Palestinians. No mention of their displacement during the War of Independence or the hardships suffered by those living in the territories conquered during the 1967 and 1973 wars is made. Nor is there a hint of United Nations Resolution 181, which proposed a two-state solution way back in 1947 but has so been rejected by Israeli mainly due to internal politics. The only controversy the exhibit is interested in is whether or not Jews living outside of Israel should have a say in its policies and future.

The strongest and most powerful exhibit in the museum is the permanent “An American Story,” which delves into the history of the Jews who settled in the Cleveland area. The earliest settlers came from the Bavarian village of Unsleben in the 1830s when Ohio was still more wilderness than not. Cleveland at this time was nothing more than a sparsely populated settlement. It did not begin its growth until the 1830s when canals and stagecoaches brought in new immigrant settlers. And it was not until 1880, according to an information sign, that “a flood of nearly 600,000 mainly Eastern European immigrants—including some 70,000 Jews—fueled the region’s growth as an industrial powerhouse in metals, motors and machine tools.”

Most immigrants from Eastern Europe had one thing in common: extreme poverty. With no savings, they were forced to live in numbers too great for the squalid tenement rooms they rented. Fortunately enlightened locals with the money to pay for their ideals decided to give this influx of immigrants aid. In 1886, for example, Hiram House on Woodland Avenue opened with the goal of helping newly arrived immigrants establish themselves and assimilate into American culture.

The strongest and most powerful exhibit in the museum is the permanent “An American Story,” which delves into the history of the Jews who settled in the Cleveland area. The earliest settlers came from the Bavarian village of Unsleben in the 1830s when Ohio was still more wilderness than not. Cleveland at this time was nothing more than a sparsely populated settlement. It did not begin its growth until the 1830s when canals and stagecoaches brought in new immigrant settlers. And it was not until 1880, according to an information sign, that “a flood of nearly 600,000 mainly Eastern European immigrants—including some 70,000 Jews—fueled the region’s growth as an industrial powerhouse in metals, motors and machine tools.”

Most immigrants from Eastern Europe had one thing in common: extreme poverty. With no savings, they were forced to live in numbers too great for the squalid tenement rooms they rented. Fortunately enlightened locals with the money to pay for their ideals decided to give this influx of immigrants aid. In 1886, for example, Hiram House on Woodland Avenue opened with the goal of helping newly arrived immigrants establish themselves and assimilate into American culture.

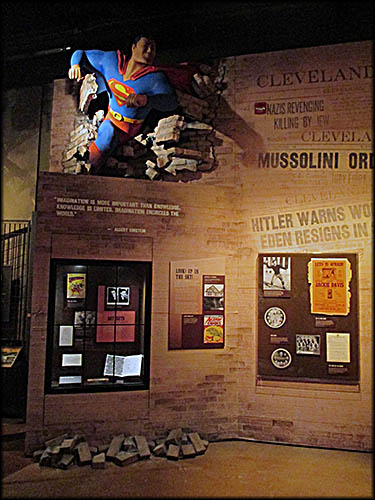

For decades to come Jews settled and did well in the Cleveland area. A mixture of displays and videos throughout the exhibit cover this very well. One of my traveling companions and I wandered into a miniature theater and got sucked into a documentary on Jewish entertainers. In another place if one looks up, one will see Superman smashing through a wall, which explains the stray bricks lying on the floor. This is because Superman’s creators, Joel Schuster and Jerry Siegel, were two Jews from Cleveland.

Despite all their accomplishments, American Jews still faced anti-Semitism. The Great Depression exacerbated the anti-Semitism that permeated American society. When Hitler rose to power in Germany, the United States kept its doors firmly closed to German Jews trying to flee because the American public wanted no more inside American borders. American anti-Semitism, awful as it was, was timid compared to that practiced in Nazi Germany, made worse when World War II broke out. By 1941 Hitler had decided that all Jews must be exterminated, and with this order the death camps were built.

An oblong room with a single entrance contains the displays about the Holocaust. Hanging on one wall is a television showing a film of the both the dead the survivors of death and concentration camps. So horrified was one of my traveling companions by this, she fled the room in disgust. This is by far the most moving and solemn place in the entire museum, and rightly so.

Despite all their accomplishments, American Jews still faced anti-Semitism. The Great Depression exacerbated the anti-Semitism that permeated American society. When Hitler rose to power in Germany, the United States kept its doors firmly closed to German Jews trying to flee because the American public wanted no more inside American borders. American anti-Semitism, awful as it was, was timid compared to that practiced in Nazi Germany, made worse when World War II broke out. By 1941 Hitler had decided that all Jews must be exterminated, and with this order the death camps were built.

An oblong room with a single entrance contains the displays about the Holocaust. Hanging on one wall is a television showing a film of the both the dead the survivors of death and concentration camps. So horrified was one of my traveling companions by this, she fled the room in disgust. This is by far the most moving and solemn place in the entire museum, and rightly so.

When I was younger I used to wake up at night hearing my mother screaming. I knew instinctively she was having a nightmare about the Holocaust. As I grew older and began to understand what my parents had suffered, I wondered if I, too, would have had the strength and faith to endure.

Louise Greenwald Gips stated,

My father, Isaac Greenwald, died in 1976. He had seen his entire family killed in the Holocaust. The Germans wiped them off the face of the earth. Only I am here to remember them.

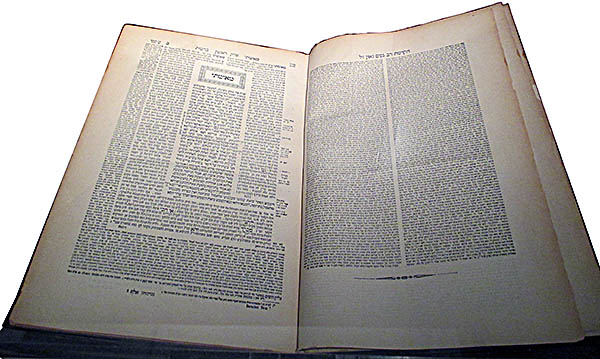

This Talmud was printed in Vilna, Lithuania.

The museum’s third exhibit, the permanent “Temple-Tifereth Israel Gallery,” contains Jewish art mainly from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It was in this exhibit that my memory was jogged. I knew the Talmud was a book important to the Jewish religion, but I couldn’t remember its purpose. An information sign explained it contains rabbinical rulings on a wide variety of subjects, the earliest of which date around 200 C.E. The Talmud on display was printed in Vilna, although I’ve no idea in what language it was written. Considering it came from Eastern Europe, I would not be surprised if it were Yiddish, about which the museum glaringly failed to mention in any significant way.

Yiddish, both as a language and literature, has a rich history, and until recently it has faced a severe decline, sparked by the murder of millions of its speakers during the Holocaust as well as the State of Israel’s decision to make Hebrew its national language. Non-Jews such as myself may not appreciate Yiddish’s contribution to America English, but it is quite extensive. Yiddish words we all use today include bubkes, schmuck, schmooze, and spiel.

Yiddish, both as a language and literature, has a rich history, and until recently it has faced a severe decline, sparked by the murder of millions of its speakers during the Holocaust as well as the State of Israel’s decision to make Hebrew its national language. Non-Jews such as myself may not appreciate Yiddish’s contribution to America English, but it is quite extensive. Yiddish words we all use today include bubkes, schmuck, schmooze, and spiel.

One of the most affecting things in this room were the quotes from Cleveland area Holocaust survivors and their relatives. Barbara Hertz Beder recalled,

After our visit, we I decided it would be appropriate to eat some Jewish cuisine. One of the places recommended to us by a museum staffer was Corky & Lenny’s Restaurant and Deli (now out of business), which is just two miles from the museum. We arrived around 1:45 on a Saturday afternoon and found it so crowded we had to wait for a table, always a good sign. I ate a delicious pot roast lunch while my traveling companions went with corned beef sandwiches, one of which also contained tongue.🕜

Here Superman is smashing into a display in the “An American Story” exhibit.

Holocaust Display

This Torah shield was made in Lubin, Poland, in 1776, but was found near Grondo in Belarus.

This miniature Torah ark was made in the year 1858 in Zhitomir, Ukraine. Unlike the one found by Indiana Jones, ghosts do not emerge and melt the faces of those who look at it.