Maritime Museum of Sandusky

The Chippewa was built in 1884 in Buffalo, New York. Before being converted to a passenger steamer, she was the revenue cutter William A. Fessendon. From 1923 to 1938, she ferried passengers to Lake Erie’s islands as well as Cedar Point.

1965 Myman Hardtop Sleeper Boat

Barometers

Crate of Liquor in the Rumrunners Exhibit

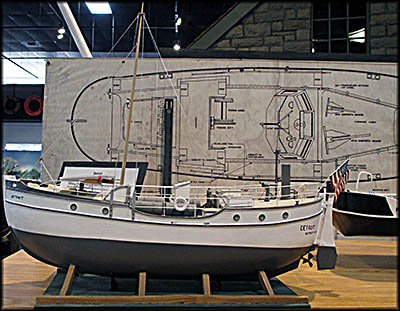

Detroit

Maritime Museum of Sandusky

Golden Age of Passenger Boats Exhibit

This Sharpie replica has an escaped slave on board.

Ice Cutters and Their Horse

Replica of the Cedar Point Lighthouse

Katie B

In a museum out building is a collection of outboard motors that enthusiasts won't want to miss.

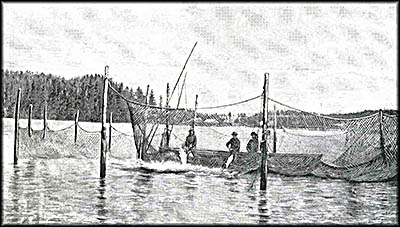

Pound Net

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Punt Boat

Pier #3 in Sandusky

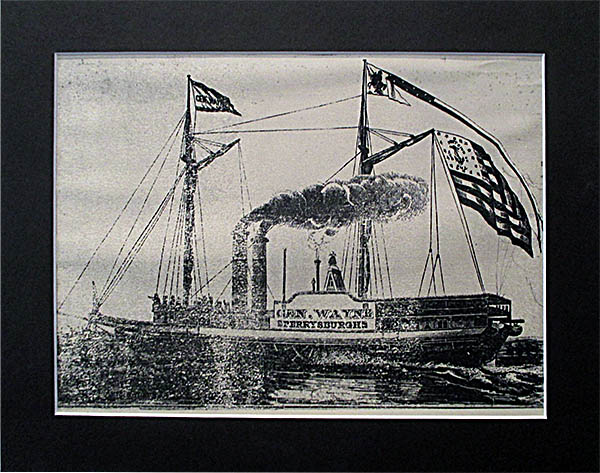

The General Wayne ended its life in a spectacular fashion: two of her boilers exploded.

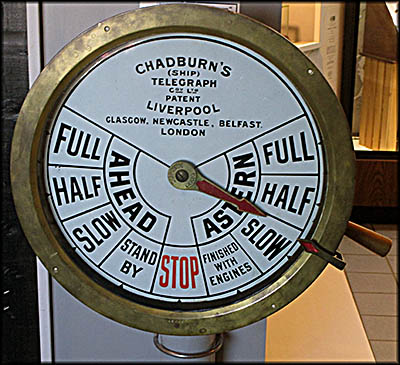

Telegraphs like this were found on the bridge. They sent a signal down to the engine room to tell the engineer what speed the captain wanted.

This tug model shows a boat with two lives. She began as Pete until sinking at its dock. Salvaged, she was rechristened the Tug Res-Q and made into a salvage vessel.

The William O. Bird began life as a revenue cutter and ended it as a fireboat.

The purpose of the Maritime Museum of Sandusky is to showcase the history of Lake Erie in general and Sandusky as a port in particular. It’s filled with models of boats associated with Sandusky or Lake Erie, one of which is that of the Detroit. This yacht, which had a length of thirty-five feet and a beam of ten feet, was constructed by the Matthews Boat Company in Port Clinton for William Scripp of Detroit. He wanted to show that its internal combustion engine was more than adequate for his one-masted sailboat to make its way from Lake Erie all the way to St. Petersburg, Russia. The Detroit’s captain, Thomas Fleming Day, agreed to command and pilot it for a different reason: he wanted to demonstrate it was perfectly safe to cross oceans in a small craft. Leaving Port Clinton on June 25, 1912, the Detroit sailed to St. Petersburg without an issue.

The museum also has original boats. One of these was built in 1905 by the Matthews Boat Company. Made of cypress and white oak, it was built for hunting in wetlands and used by the Ottawa Shooting Club into the late 1970s. During its restoration, its rotted decking was replaced with plywood. For those who like to push buttons (and I’ve been known to be quite the enthusiast), the boat’s exhibit has an array of them that, when pressed, play sounds of some of the critters you’d find in a marshy area.

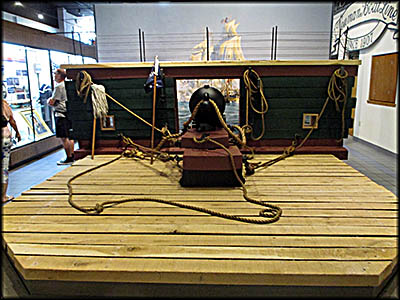

The museum has a scaled down replica of another type of craft known as the Great Lakes Sharpie. This was a sailboat equipped with one or two masts used for commercial fishing. Fisherman threw pound nets Over its sides, a way of catching fish en masse first developed in Scotland and introduced into Lake Erie in the 1850s. Sandusky fishermen aggressively spread their nets into Canadian waters, making their city a major exporter of fresh fish and causing a conflict with Canada, which didn’t take kindly to Americans fishing in its territorial waters.

Sometimes Sharpies carried more than just fishermen. The replica in the museum includes one taking an escaped slave to freedom. In it there is also baby doll, although whether it belongs to the escaped slave or fisherman or one of the two just liked to carry dolls around, I can’t say. The point is that Sharpies were sometimes, though not often, used as a means for the Underground Railroad to ferry escaped slaves to Detroit or Buffalo from which they could quickly reach Canada and permanent freedom.

Because Ohio bordered two slave states as well as Lake Erie, it had the most Underground Railroad traffic of any state, and Sandusky was one of the Underground Railroad’s prime destinations. Here some of the most active members of the Underground Railroad belonged to the Zion Baptist Church, which was founded in 1845 by free Blacks, some of them former slaves. After moving to Decatur Street, it was renamed the First Regular Anti-Slavery Baptist Church.

The museum also has original boats. One of these was built in 1905 by the Matthews Boat Company. Made of cypress and white oak, it was built for hunting in wetlands and used by the Ottawa Shooting Club into the late 1970s. During its restoration, its rotted decking was replaced with plywood. For those who like to push buttons (and I’ve been known to be quite the enthusiast), the boat’s exhibit has an array of them that, when pressed, play sounds of some of the critters you’d find in a marshy area.

The museum has a scaled down replica of another type of craft known as the Great Lakes Sharpie. This was a sailboat equipped with one or two masts used for commercial fishing. Fisherman threw pound nets Over its sides, a way of catching fish en masse first developed in Scotland and introduced into Lake Erie in the 1850s. Sandusky fishermen aggressively spread their nets into Canadian waters, making their city a major exporter of fresh fish and causing a conflict with Canada, which didn’t take kindly to Americans fishing in its territorial waters.

Sometimes Sharpies carried more than just fishermen. The replica in the museum includes one taking an escaped slave to freedom. In it there is also baby doll, although whether it belongs to the escaped slave or fisherman or one of the two just liked to carry dolls around, I can’t say. The point is that Sharpies were sometimes, though not often, used as a means for the Underground Railroad to ferry escaped slaves to Detroit or Buffalo from which they could quickly reach Canada and permanent freedom.

Because Ohio bordered two slave states as well as Lake Erie, it had the most Underground Railroad traffic of any state, and Sandusky was one of the Underground Railroad’s prime destinations. Here some of the most active members of the Underground Railroad belonged to the Zion Baptist Church, which was founded in 1845 by free Blacks, some of them former slaves. After moving to Decatur Street, it was renamed the First Regular Anti-Slavery Baptist Church.

The museum’s information sign says “the congregation members would hide, feed and clothe refugee slaves at the church while they waited for passage to Canada.” This I must dispute. With a name like “First Regular Anti-Slavery Baptist Church” run by city’s small Black population, only the dimmest slavecatcher would fail to make every effort to search the place thoroughly. And because of the Fugitive Slave Act, they had the right to ask local judges to issues search warrants, which many did. It’s more likely the congregants hid the runaways in their own homes or in the houses or farms of people not associated with the church.

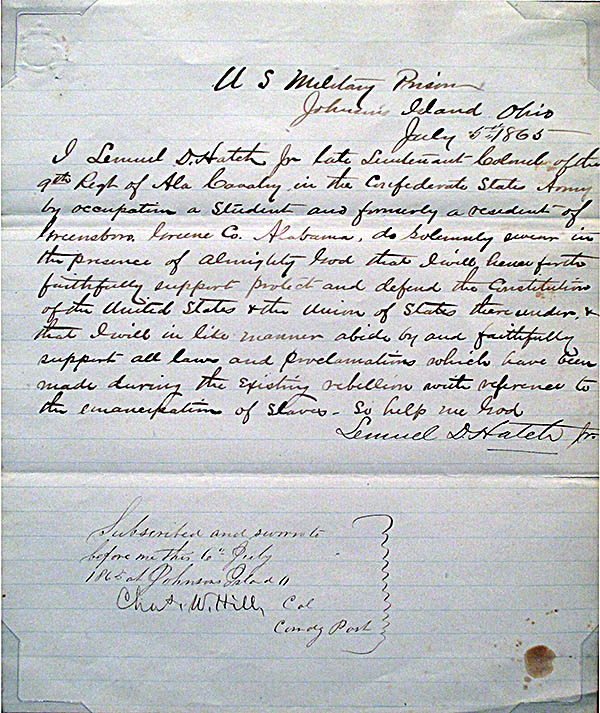

When the Civil War broke out over the issue of slavery, it quickly reached Sandusky Bay with the opening of a prisoner of war camp on Johnson’s Island that primarily housed Confederate officers. At first the prisoners were treated well, but overcrowding and other factors turned it into a hellhole where 200 prisoners or so died. Upon General Robert E. Lee’s surrender, some of the prisoners signed oaths of allegiance of the United States to secure their immediate release, which they called “Swallowing the Eagle.”

The Johnson’s Island prison became the object of a Confederate plot cooked up by Confederate officer John Yates Beall. The plan involved he and his men seizing the steam transport Philo Parsons while at the same time Charles Cole and some of Sandusky’s Copperheads (Southern sympathizers) would steal the only Union gunboat on Lake Erie, the USS Michigan, by drugging its officers and crew. Cole was caught before executing his part, so when he failed to a rocket indicating he was ready, Beall’s men on the Philo Parsons mutinied and insisted on heading to Canada. Here they tried and failed to burn the Philo Parsons. (A more detailed version of this account is relayed in Chapter 6 of my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio). While the prisoners would’ve welcomed Beall had he come, many plotted their own escapes. A few tried to walk across the frozen lake to Canada, a more dangerous prospect than they might have realized.

When the Civil War broke out over the issue of slavery, it quickly reached Sandusky Bay with the opening of a prisoner of war camp on Johnson’s Island that primarily housed Confederate officers. At first the prisoners were treated well, but overcrowding and other factors turned it into a hellhole where 200 prisoners or so died. Upon General Robert E. Lee’s surrender, some of the prisoners signed oaths of allegiance of the United States to secure their immediate release, which they called “Swallowing the Eagle.”

The Johnson’s Island prison became the object of a Confederate plot cooked up by Confederate officer John Yates Beall. The plan involved he and his men seizing the steam transport Philo Parsons while at the same time Charles Cole and some of Sandusky’s Copperheads (Southern sympathizers) would steal the only Union gunboat on Lake Erie, the USS Michigan, by drugging its officers and crew. Cole was caught before executing his part, so when he failed to a rocket indicating he was ready, Beall’s men on the Philo Parsons mutinied and insisted on heading to Canada. Here they tried and failed to burn the Philo Parsons. (A more detailed version of this account is relayed in Chapter 6 of my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio). While the prisoners would’ve welcomed Beall had he come, many plotted their own escapes. A few tried to walk across the frozen lake to Canada, a more dangerous prospect than they might have realized.

Lake Erie, which is an inland sea, is an exceedingly dangerous body of water to cross in any season. In the early days of Americans settlements along its shores, maritime traffic was limited supporting military outposts and the fur trade. The 1825 opening of the Erie Canal in New York changed all that. With easy access to the lake, people flooded upon it, many choosing to settle along its shores. A decade later, the Lake Erie & Mad River Railroad connected Sandusky to Ohio’s Miami-Erie Canal, which stretched from Cleveland to Cincinnati. This link caused Sandusky as a port to boom.

“Boom” is also a good way to describe the earliest steamboats and ships sailing on Lake Erie. Often using poorly constructed boilers with crews unfamiliar with how steam power worked, boiler explosions killed and estimated 1,800 people and destroyed 230 steam-powered craft between 1816 and 1848. The first steamboat to sail upon Lake Erie was the sidewheel Walk-in-the-Water. Buit in Buffalo, New York, it was launched on August 18, 1818. Just three years later on November 1, it was caught in a gale caught while departing Buffalo, and the wind smashed it onto a beach. Although all eighteen passengers survived, the $10,000 worth of cargo didn’t.

“Boom” is also a good way to describe the earliest steamboats and ships sailing on Lake Erie. Often using poorly constructed boilers with crews unfamiliar with how steam power worked, boiler explosions killed and estimated 1,800 people and destroyed 230 steam-powered craft between 1816 and 1848. The first steamboat to sail upon Lake Erie was the sidewheel Walk-in-the-Water. Buit in Buffalo, New York, it was launched on August 18, 1818. Just three years later on November 1, it was caught in a gale caught while departing Buffalo, and the wind smashed it onto a beach. Although all eighteen passengers survived, the $10,000 worth of cargo didn’t.

Another steamboat of note, the S.S. Anthony Wayne, was built in Perrysburg, Ohio, in 1837. On April 28, 1850, while passing Vermillion, two of its starboard boilers exploded, knocking its captain out of his bed. Although he survived, many crewmen and passengers were burned by scalding water. Eleven crewmen and between fifty to ninety passengers drowned when it sank.

Passenger traffic on the lake fell considerably after the Panic of 1857, but by the early 1870s it rebounded. During this time, resorts started up on many of the lake’s islands, making them popular warm weather destinations. One of these resorts was at Cedar Point. Although technically a peninsula, reaching overland was difficult. Those who wished to visit took a boat, one of which was the Young Reindeer. It ferried passengers there and back for 25 cents.

Cedar Point began is transformation from a resort into an amusement park when George Authur Boeckling purchased the peninsula in 1897. Within a decade of taking over, ferries couldn’t keep up with demand, so he had the steam-powered G.A. Boeckling constructed to accommodate them. Capable of carrying up to 2,000 passengers, it made its maiden voyage on June 26, 1909. Boeckling decided to accommodate automobiles by building a road to the park, a route now known as the Chaussee. Much of the original was destroyed just a few years after construction, so the route altered when reconstructed.

Passenger traffic on the lake fell considerably after the Panic of 1857, but by the early 1870s it rebounded. During this time, resorts started up on many of the lake’s islands, making them popular warm weather destinations. One of these resorts was at Cedar Point. Although technically a peninsula, reaching overland was difficult. Those who wished to visit took a boat, one of which was the Young Reindeer. It ferried passengers there and back for 25 cents.

Cedar Point began is transformation from a resort into an amusement park when George Authur Boeckling purchased the peninsula in 1897. Within a decade of taking over, ferries couldn’t keep up with demand, so he had the steam-powered G.A. Boeckling constructed to accommodate them. Capable of carrying up to 2,000 passengers, it made its maiden voyage on June 26, 1909. Boeckling decided to accommodate automobiles by building a road to the park, a route now known as the Chaussee. Much of the original was destroyed just a few years after construction, so the route altered when reconstructed.

During the Great Depression auto traffic nearly disappeared, so a trip to Cedar Point on the Boeckling was free in these lean times. Although the park suffered from lack of resources during the rationing of World War II, the Boeckling was well-maintained so she could pass inspections. By 1950 most ferries were diesel powered, a much cheaper and more efficient means of running a boat or ship, making the Boeckling more costly to operate than necessary, so it was retired in 1951 on Labor Day. Although many in Sandusky had much affection for it, businesses aren’t afflicted by nostalgia, so Cedar Point sold it to a Wisconsin building company that used it as a floating warehouse for the next thirty years.

When Cedar Point opened a beer garden, much of its lager was brewed in Sandusky by the Kuebeler-Stang Brewing and Malting Company, which had formed in 1896 with the merger of the city’s largest breweries. It could produce 350,000 barrels a day. At this time, too, the islands hosted a number of successful wine makers. All this ended with the implementation of Prohibition in 1920, which outlawed the manufacture and sale of all alcoholic beverages save for ones used for medicinal and religious purposes. Prohibition didn’t curb demand for alcoholic beverages.

But for states bordering Canada, plenty of the stuff could be found a across the border. Enterprising boat owners living along Lake Erie’s southern shore sailed there to acquire it, then sold it at inflated prices back home. Those who used their boats for this purpose were called rumrunners, many of whom were fishermen, who often sailed at known in operations known as “fishing for midnight herring.”

Others invested in fast speedboats that could outrun anything enforcement agencies had on the lake. One such person was John Zetzer, owner of the Port Clinton Marina along the Portage River. Equipping his boat Rum Runner with two 500 horsepower engines, he claimed he could reach Ontario in seventeen minutes. He sold his cargo to the likes of Al Capone and Detroit’s Purple Gang.

When Cedar Point opened a beer garden, much of its lager was brewed in Sandusky by the Kuebeler-Stang Brewing and Malting Company, which had formed in 1896 with the merger of the city’s largest breweries. It could produce 350,000 barrels a day. At this time, too, the islands hosted a number of successful wine makers. All this ended with the implementation of Prohibition in 1920, which outlawed the manufacture and sale of all alcoholic beverages save for ones used for medicinal and religious purposes. Prohibition didn’t curb demand for alcoholic beverages.

But for states bordering Canada, plenty of the stuff could be found a across the border. Enterprising boat owners living along Lake Erie’s southern shore sailed there to acquire it, then sold it at inflated prices back home. Those who used their boats for this purpose were called rumrunners, many of whom were fishermen, who often sailed at known in operations known as “fishing for midnight herring.”

Others invested in fast speedboats that could outrun anything enforcement agencies had on the lake. One such person was John Zetzer, owner of the Port Clinton Marina along the Portage River. Equipping his boat Rum Runner with two 500 horsepower engines, he claimed he could reach Ontario in seventeen minutes. He sold his cargo to the likes of Al Capone and Detroit’s Purple Gang.

Rumrunning from Canada into Ohio didn’t end with Prohibition. In 1967 the Ohio Department of Liquor put into service a 32 foot boat to go after liquor smugglers. The vessel looked like other craft of its type so as to be inconspicuous, but it had a secret. It was powered by two 320 horsepower engines that could take it up to 45 miles-per-hour, allowing it to catch just about anything on the lake. The engines sprouted arcs of water that looked like rooster tails.

The boat’s time as a revenue cutter was short. In the early 1970s it was given to the Ohio Division of Watercraft, but that agency deemed the vessel to large for its needs and put it into a drydock at the Venetian Marina in Sandusky. The City of Sandusky took possession of it in in 1976 and deployed it as a fireboat. It was rechristened the William O. Bird in honor of a Sandusky firefighter killed while doing his duty and furnished with firefighting equipment.

To see the William O. Bird you have to head outside via a door in a room with an exhibit about the history of Sandusky Bay’s shipping lanes and Sandusky’s coal piers. Here you’ll see an impressive model of Pier #3, construction for which began in 1937 by the Pennsylvania Railroad. To allow larger vessels to navigate the shallow Sandusky Bay, a new shipping channel was dug, a process that removed 2,500,000 cubic yards of soil, silt and sand. Coal was already being shipped from Piers #1 and #2, but this new one had a 117 feet tall electric coal dumper than could pick up and tip coal railroad cars over. It was known as “the Giant with the Gentle Hands.” The construction of Pier #3 was timely. World War II erupted soon after, and during this conflict over 14 billion tons of coal was shipped out of Sandusky for the war effort.🕜

The boat’s time as a revenue cutter was short. In the early 1970s it was given to the Ohio Division of Watercraft, but that agency deemed the vessel to large for its needs and put it into a drydock at the Venetian Marina in Sandusky. The City of Sandusky took possession of it in in 1976 and deployed it as a fireboat. It was rechristened the William O. Bird in honor of a Sandusky firefighter killed while doing his duty and furnished with firefighting equipment.

To see the William O. Bird you have to head outside via a door in a room with an exhibit about the history of Sandusky Bay’s shipping lanes and Sandusky’s coal piers. Here you’ll see an impressive model of Pier #3, construction for which began in 1937 by the Pennsylvania Railroad. To allow larger vessels to navigate the shallow Sandusky Bay, a new shipping channel was dug, a process that removed 2,500,000 cubic yards of soil, silt and sand. Coal was already being shipped from Piers #1 and #2, but this new one had a 117 feet tall electric coal dumper than could pick up and tip coal railroad cars over. It was known as “the Giant with the Gentle Hands.” The construction of Pier #3 was timely. World War II erupted soon after, and during this conflict over 14 billion tons of coal was shipped out of Sandusky for the war effort.🕜

Partial Deck of a Ship from the Battle of Lake Erie

Written oath by from Johnson’s Island prison camp by Colonel Chas. Wittill pledging allegiance to the United States. This was known as “Swallowing the Eagle” by Confederal prisoners of war.