McLeod Plantation Historic Site

McLeod Plantation Historic Site

This was originally the front of the main house, but it was designated as the back the 20th century.

This was originally the back of the main house, but it was designated as the front the 20th century.

Inside the Main House

Centuries Old Live Oak Tree

View of the "front" from

inside the main house.

inside the main house.

At McLeod Plantation, the live tour doesn’t go into the house, but you can download an app that takes you there along with eleven other places on the grounds. My traveling companion and I declined to do the app but did visit the house before our tour started. Within I was more amazed by what I didn’t see rather than what I did. It’s not furnished save for a couple of rugs, information signs and photos hanging on the walls. In several rooms there is a focus on the Gullah-Geechee people who still prosper in the region. A couple rooms contain some contemporary photos of them.

On my third visit to Charleston, South Carolina, I wanted to see McLeod (pronounced "McCloud)" Plantation Historic Site on James Island because I’d heard about it on the BBC World Service. That news organization aired a story about how visitors to the plantation were complaining that instead of focusing on the McLeod family, tours examined the lives of the plantation’s slaves. As a trained and sometimes active historian, I think it’s vital to examine history from the perspective of all its participants, so I applaud this. Having visited many a former slave plantation over the years, including Monticello, it is rare indeed that such places focus on anything but the plantation’s family and how it lived before the Civil War. Most of these houses are treated like pristine museums. Go to the dining room and you’ll see that the silverware and china laid out just so. In the parlor, notice this piece of original family furniture, and here in the hall is family chamber pot. This is not a bad thing so long as it’s contrasted with how the slaves made the money the family lived off of. The McLeod Plantation in any case does offer much information about its namesake family’s history.

Years ago on the History Channel there was a British-made television series called The Story of English that included a visit with the Gullah-Geechee people and their unique creole language that incorporates English and a variety of Central and West African languages. Called Geechee, it is the only African-creole language native to the United States. The Gullah-Geechees’ ancestors were kidnapped from West and Central Africa and forced to settle mainly on the sea and barrier islands along the coasts of South Carolina and northern Georgia. Gullah-Geechee culture is known for its woven baskets, handmade nets to catch fish, a unique musical tradition, and a rich spiritual religion. Their way of life these days is threatened by gentrification and the younger generation losing interest in their traditional culture.

William McLeod made his money the old fashioned way: he married into it. His wife was a Middleton, one of the area’s richest families. The Middletons owned nineteen plantations and 3,000 slaves. The McLeod family were considered middle class. At the outbreak of the Civil War, they had about 100 slaves. They were the fourth family to own the land when William purchased it in 1851. It was he who had the present house built in 1854. Even though the planation encompassed 3,700 acres, the family never employed an overseer. William grew sea island cotton.

Although it looks grand from the outside, the house is relatively small. The first floor is comprised of five rooms plus a kitchen added in the early 1900s. The second floor, which you can’t see because it has been repurposed as offices, has a hall, four bedrooms, and a bath,. The third floor is the smallest. It consists of just two rooms and a short hall. Here it is likely the house slaves lived. Presuming this to be the case, surely mother and son Isabella and Daniel Pickney occupied one of its rooms. Never one to miss an opportunity to employ child labor, the McLeods gave Daniel his own duties, one of which was to stand silently in the dining room or parlor swatting flies away from family members. Isabella’s duties included emptying chamber pots and serving as the nanny for William’s daughter, Anne.

William McLeod made his money the old fashioned way: he married into it. His wife was a Middleton, one of the area’s richest families. The Middletons owned nineteen plantations and 3,000 slaves. The McLeod family were considered middle class. At the outbreak of the Civil War, they had about 100 slaves. They were the fourth family to own the land when William purchased it in 1851. It was he who had the present house built in 1854. Even though the planation encompassed 3,700 acres, the family never employed an overseer. William grew sea island cotton.

Although it looks grand from the outside, the house is relatively small. The first floor is comprised of five rooms plus a kitchen added in the early 1900s. The second floor, which you can’t see because it has been repurposed as offices, has a hall, four bedrooms, and a bath,. The third floor is the smallest. It consists of just two rooms and a short hall. Here it is likely the house slaves lived. Presuming this to be the case, surely mother and son Isabella and Daniel Pickney occupied one of its rooms. Never one to miss an opportunity to employ child labor, the McLeods gave Daniel his own duties, one of which was to stand silently in the dining room or parlor swatting flies away from family members. Isabella’s duties included emptying chamber pots and serving as the nanny for William’s daughter, Anne.

Isabella was the bastard daughter of a white planter and enslaved mother. She and Daniel were given to the William specifically so she could serve as nanny for Anne, who had a rough childhood. In 1859, when she was just six years old, her mother died. Next followed her stepmother. When the Civil War broke out, her father, although exempt from military service because of his age (he was forty-one), voluntarily joined the calvary and headed to Virginia to fight. Most planters became officers but William began and ended his career as a mere private. In February 1865 he headed home to see his family only to die of pneumonia at Moncks Corner, just twenty-nine miles to the north of James Island as the crow flies. Isabella became Anne’s surrogate mother. On her deathbed in 1935, Anne supposedly called out for the long dead Isabella.

In 1808 the United States barred the importation of slaves. It didn’t stop smugglers but did reduce the number brought to America to a trickle. This made slave women valuable as breeding machines. Camps for this purpose were created where girls as young as ten to twelve were subjected to repeated raping by enslaved men. Only the biggest and strongest men were used because they’d been so dehumanized their owners treated them like cattle instead of human beings.

Pregnancy, whether willing or not, didn’t exclude an enslaved woman from doing work. She still had to cook, churn butter, wash, clean, and so forth. Since wives of plantation owners rarely reared their own children, enslaved women did that, too. Some also served as wet nurses. They often had no assistance when giving birth, although other slave women would help if possible. Slave traders frequently bid on unborn slave children, and it wasn’t unknown for an infant to be snatched from its mother shortly after birth.

In 1808 the United States barred the importation of slaves. It didn’t stop smugglers but did reduce the number brought to America to a trickle. This made slave women valuable as breeding machines. Camps for this purpose were created where girls as young as ten to twelve were subjected to repeated raping by enslaved men. Only the biggest and strongest men were used because they’d been so dehumanized their owners treated them like cattle instead of human beings.

Pregnancy, whether willing or not, didn’t exclude an enslaved woman from doing work. She still had to cook, churn butter, wash, clean, and so forth. Since wives of plantation owners rarely reared their own children, enslaved women did that, too. Some also served as wet nurses. They often had no assistance when giving birth, although other slave women would help if possible. Slave traders frequently bid on unborn slave children, and it wasn’t unknown for an infant to be snatched from its mother shortly after birth.

Slaves who cooked the McLeod’s meals worked the kitchen, which was an out building far enough from the main house that if it burned it wouldn’t take everything else with it. Despite a proximity to such an abundance of food, slaves received very little of it. The Gullah slaves on the planation ate the stuff their masters wouldn’t, which is why neck bones, chitlins (made from intestines), and pigs’ feet became a part of their diet, as did red rice, black-eyed peas, and okra. To taste traditional Gullah fair, our guide, Olivia Williams, recommended eating at Hannibal’s Kitchen in downtown Charleston, or Gillie’s Seafood on James Island. We visited the latter, and although I despise seafood, Gillie’s had plenty of other fare and I got some excellent baked chicken smothered in barbeque sauce.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, sea island cotton was the most desirable type in the world, but getting the seeds out of it was exceedingly time consuming, limiting its value. Then came the cotton gin that automatically separated out the seeds, increasing this type of cotton’s value exponentially because it could now be produced in large quantities. Eli Whitney patented the cotton gin but it’s possible the idea either originated with Catherine Greene, widow of Revolutionary hero Nathaniel Green, or a slave named Sam. The McLeod Plantation’s original gin house is still on the grounds, although you can’t go inside it.

Everything changed for both masters and slaves when South Carolina seceded from the United States followed by ten other slave states. They had one reason for this and one only: to preserve slavery. It was only after the Civil War ended that Confederate survivors decided to rewrite history and developed the Lost Cause mythology. James Island quickly became a keystone to the defense of Charleston with McLeod Plantation, hidden from passing Union vessels and close to railroad supply lines, being one of its linchpins. In 1862 General States Rights Gist (that’s really his name) evacuated all civilians from James Island including the McLeod family. In 1863 he made the family’s plantation his headquarters.

One of the regiments that paraded through Charleston after Union forces occupied it was the all-black 55th Massachusetts (led, alas, but white officers—no one in the U.S. Army was enlightened enough to put African Americans in charge). The 55th settled on James Island and made McLeod Planation its headquarters. One of its privates, George Smothers, left his autograph on a third floor wall.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, sea island cotton was the most desirable type in the world, but getting the seeds out of it was exceedingly time consuming, limiting its value. Then came the cotton gin that automatically separated out the seeds, increasing this type of cotton’s value exponentially because it could now be produced in large quantities. Eli Whitney patented the cotton gin but it’s possible the idea either originated with Catherine Greene, widow of Revolutionary hero Nathaniel Green, or a slave named Sam. The McLeod Plantation’s original gin house is still on the grounds, although you can’t go inside it.

Everything changed for both masters and slaves when South Carolina seceded from the United States followed by ten other slave states. They had one reason for this and one only: to preserve slavery. It was only after the Civil War ended that Confederate survivors decided to rewrite history and developed the Lost Cause mythology. James Island quickly became a keystone to the defense of Charleston with McLeod Plantation, hidden from passing Union vessels and close to railroad supply lines, being one of its linchpins. In 1862 General States Rights Gist (that’s really his name) evacuated all civilians from James Island including the McLeod family. In 1863 he made the family’s plantation his headquarters.

One of the regiments that paraded through Charleston after Union forces occupied it was the all-black 55th Massachusetts (led, alas, but white officers—no one in the U.S. Army was enlightened enough to put African Americans in charge). The 55th settled on James Island and made McLeod Planation its headquarters. One of its privates, George Smothers, left his autograph on a third floor wall.

As the war came to a close, thousands of ex-slaves flooded James Island, leading to a humanitarian crisis. Congress created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedman, and Abandoned Lands to help deal with it. James Island was divvied up in parcels given to these former slaves. The Freedmen’s Bureau, as it became known, was tasked with establishing schools, helping to foster labor contracts, and taking care of the health of these new settlers. The Bureau set up its headquarters at McLeod Plantation. Then came a smallpox epidemic from Fall 1865 through Winter 1866 that reduced the total number of refugees from about 4,000 to 2,100. Unfortunately for the survivors, the island’s previous planation owners managed to get the government to give them their land back, ending this localized forty acres and a mule enterprise.

William McLeod II and other planters on the island returned to growing sea island cotton to restore their former prestige if not wealth. Jim Crow laws allowed them to exploit those African Americans who hadn’t left the island. William II’s son, William E. McLeod (born in 1885), had to abandon sea island cotton when the boll weevil decimated that crop. He replaced it with vegetable gardens and selling or renting parts of his land to others. Six former slave houses were moved closer to the main house, made more habitable with the addition of things such as wooden floors, and in the 1940s William E. rented them to descendants of the plantation’s original slaves for a mere $27 a month. Upon his death in 1990, the plantation’s new caretaker, Charleston County Parks, evicted them, one last indignity for the generations of African Americans who lived here.

In 1939 Gone with the Wind, the highest grossing movie in U.S. history (when adjusted for inflation), came out. This presented William E. and other plantation owners with an opportunity. The movie’s heavily romanticized version of life on a plantation transformed real ones into hot tourist destinations. Capitalizing on this, William E. added an elaborate porch to the back of his house to make it look like one seen in the Gone with the Wind. Now the house’s back became the front and vice versa. It was he who arranged for the house to become a museum after his death.🕜

William McLeod II and other planters on the island returned to growing sea island cotton to restore their former prestige if not wealth. Jim Crow laws allowed them to exploit those African Americans who hadn’t left the island. William II’s son, William E. McLeod (born in 1885), had to abandon sea island cotton when the boll weevil decimated that crop. He replaced it with vegetable gardens and selling or renting parts of his land to others. Six former slave houses were moved closer to the main house, made more habitable with the addition of things such as wooden floors, and in the 1940s William E. rented them to descendants of the plantation’s original slaves for a mere $27 a month. Upon his death in 1990, the plantation’s new caretaker, Charleston County Parks, evicted them, one last indignity for the generations of African Americans who lived here.

In 1939 Gone with the Wind, the highest grossing movie in U.S. history (when adjusted for inflation), came out. This presented William E. and other plantation owners with an opportunity. The movie’s heavily romanticized version of life on a plantation transformed real ones into hot tourist destinations. Capitalizing on this, William E. added an elaborate porch to the back of his house to make it look like one seen in the Gone with the Wind. Now the house’s back became the front and vice versa. It was he who arranged for the house to become a museum after his death.🕜

This kitchen was used by slaves to prepare meals for the McLeod family.

On the Grounds

(Cotton) Gin House

Different views of one of the out buildings.

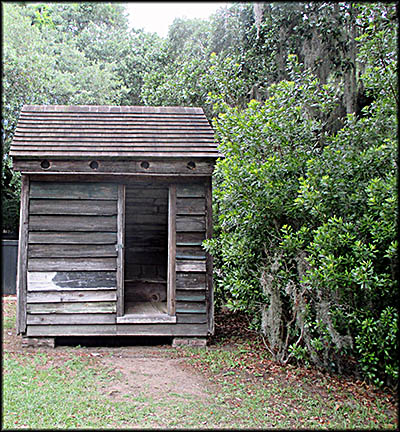

No indoor plumbing for the McLeod family. This is an outhouse.

These former slave quarters were modernized and lived in by the descendants of McLeod Plantation's slaves.