Mid-American Windmill Museum

It never occurred to me that there are windmill enthusiasts in this world, but I really ought not be surprised. There are aficionados for just about everything, including London buses, the breeding of candy/toffee ball-colored snakes, and the rehabilitation of the tarnished reputation of England’s King Richard III. In the early 1990s a windmill devotee founded the Mid-American Windmill Museum in Kendallville, Indiana.

After paying a modest entry fee for this unusual museum, I went into a room to watch a video about wind and windmills that was clearly made for children attending elementary school. And unless you bring kids of that age with you, I suggest skipping it. The video room is just one part of an historic barn that contains a wide collection of the windmills, model windmills of the sort one puts in one’s front yard, and a number of information signs. There are also buttons that activate select windmills. The vanes of one, for example, move inward at a sharp angle, this being a feature owners used to prevent an exceptionally powerful wind from doing damage. A volunteer gave me a tour of the barn’s contents. A retiree, she herself is a windmill enthusiast, at one point proudly telling me about the time someone wanted to piece together two different manufacturers of windmills for display and how that was just wrong and she put a stop to that! Her passion for windmills was infectious.

This mechanical tool has a surprisingly socio-economic history. In the days before flour was available year round in stores, one had to go either grind their grain by hand (a laborious and time consuming process) or, in areas with lots of rivers, have the local watermill do it. The drawback was that the mills owners had a monopoly that allowed them to charge exorbitant prices. Wind-powered mills began appearing as competition.

After paying a modest entry fee for this unusual museum, I went into a room to watch a video about wind and windmills that was clearly made for children attending elementary school. And unless you bring kids of that age with you, I suggest skipping it. The video room is just one part of an historic barn that contains a wide collection of the windmills, model windmills of the sort one puts in one’s front yard, and a number of information signs. There are also buttons that activate select windmills. The vanes of one, for example, move inward at a sharp angle, this being a feature owners used to prevent an exceptionally powerful wind from doing damage. A volunteer gave me a tour of the barn’s contents. A retiree, she herself is a windmill enthusiast, at one point proudly telling me about the time someone wanted to piece together two different manufacturers of windmills for display and how that was just wrong and she put a stop to that! Her passion for windmills was infectious.

This mechanical tool has a surprisingly socio-economic history. In the days before flour was available year round in stores, one had to go either grind their grain by hand (a laborious and time consuming process) or, in areas with lots of rivers, have the local watermill do it. The drawback was that the mills owners had a monopoly that allowed them to charge exorbitant prices. Wind-powered mills began appearing as competition.

The first windmill design appears in the historical record between 400 and 100 c.e. Invented in Iran, the Persian windmill had a horizontal sail wheel that powered a grinding mill. Brought to Europe by Muslims invading Spain as well as returning Crusaders, this design didn’t worked very well in less windy areas, so it was replaced by the post windmill, a type that had vertical sails much higher off the ground to better catch the wind. The Dutch, surely the one people we most associate with windmills (save, perhaps, for Don Quixote), invented the hollow post windmill, or wipmolen, used mainly to drain water. The Dutch also created the Smock Windmill, which had a moving wheel that could catch the wind from any direction. The first windmill in North America was erected about twenty miles away from Jamestown near the mouth of the James River. Built and operated by Sir George Yardley in 1620, it powered a grinding wheel.

The need for windmills wasn’t all that great in the early days of the American colonies and United States because the many rivers in the region made water the power of choice for grinding mills. It wasn’t until Americans began settling beyond the Mississippi that this changed, for here water was much scarcer. Now there was a need to extract it from underground sources.

The need for windmills wasn’t all that great in the early days of the American colonies and United States because the many rivers in the region made water the power of choice for grinding mills. It wasn’t until Americans began settling beyond the Mississippi that this changed, for here water was much scarcer. Now there was a need to extract it from underground sources.

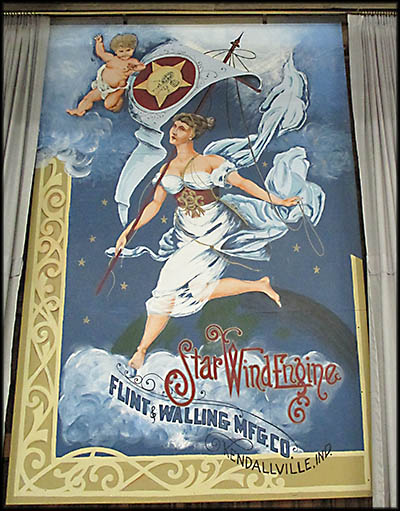

To do this job, a new kind of windmill capable of surviving the American West’s powerful windstorms appeared. Designed by Daniel Halladay, it received a patent in 1854. Unlike earlier designs, instead of sails it had four vanes that would fold if the wind wheel spun too fast. In time the appropriately-named Leonard Wheeler created a more efficient way of regulating a wind wheel’s speed that involved rudders and weights. The high demand for windmills in the American West created a windmill-making boom that, according to one of the museum’s information signs, made “Northern Indiana, Southern Michigan, and Northwestern Ohio … [a] major area of the manufacture of the self-regulating ‘American’ windmill.… Within a radius of 80 miles around Kendallville there were 94 windmill producers,” most of which lasted just a couple of years. Windmill sales plummeted during the Great Depression in part because rural electrification allowed farmers to replace their windmills with electric pumps.

Most of the above I learned in the barn. Upon leaving that and going outside. I made my way to a large red building whose purpose I couldn’t discern. Opening its door resulted in a not very loud but definitely annoying screeching sound. I had set off the burglar alarm. Surely this meant there must be something of value within. What treasures did it hold? Not much. It was a workshop that only someone with a need for lumber and windmill parts would want to raid. The alarm persisted, so I made myself scarce and headed to look at the outdoor exhibits.

The only windmill at the museum that had sails was the Roberson, which is a replica of the first one ever built in North America. It was far more interesting on the outside than in. Sadly, I didn’t find an monster made of out human cadavers within. The Aermotor power mill was nothing more than a standard windmill with its base enclosed by a building that contained nothing of particular interest. After a quick trip under a short covered bridge made for pedestrians, I decided to call it a day. That, and I wanted to get away before the police responded to the burglar alarm.

The only windmill at the museum that had sails was the Roberson, which is a replica of the first one ever built in North America. It was far more interesting on the outside than in. Sadly, I didn’t find an monster made of out human cadavers within. The Aermotor power mill was nothing more than a standard windmill with its base enclosed by a building that contained nothing of particular interest. After a quick trip under a short covered bridge made for pedestrians, I decided to call it a day. That, and I wanted to get away before the police responded to the burglar alarm.

This is the repair building.

It has a touchy burglar alarm.

It has a touchy burglar alarm.

This post windmill contained no monsters.

Stills from Frankenstein (1931)

Unless you have a passion for windmills greater than the Pope’s faith in God, or you live nearby, I wouldn’t recommend coming from a long distance just to visit this museum. However, if happen to be in the area like I was, then I’d say it is worth seeing. If you need a stopover on a long trip, here is as good a place as any. I suggest staying at Kendallville’s Holiday Express. It is a real hotel (that being a place in which the room doors are inside and not out). And it has the world’s most friendly staff. The rooms aren’t too bad, either. Mine had a good sized fridge (which froze my bottled water—oops), a microwave, and the obligatory coffee maker. When I went to breakfast the next morning, the staff asked me several times if I needed assistance—I didn’t—and even offered to get me some butter despite the fact I was only a few steps away from the supply. I did ask for one thing: a winning lottery ticket. This, alas, they didn’t have to give.🕜