Montrose Historical & Telephone Pioneer Museum

Museum Exterior

This is a Model 1510 phone made by Sweden's Ericsson Telephone Company.

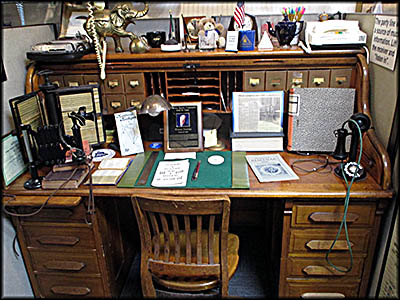

Wyman Jennings' Desk

Classic Bakelite Desk Phone

Candlestick Phones

This basket was made by Zulus in South Africa. It's made out of telephone wires.

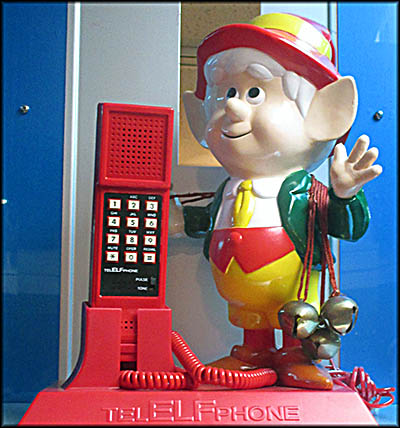

Ernie the Keebler Elf Phone

Harley-Davidson Phone

One of the many phone displays.

Superman's Telephone Booth

Periscope Phone

Telegraphs that you can play with.

Working at a Switchboard

Genuine Telephone Pole Insulator

Local History Room

Quilts

Syringe from the Pharmacy Exhibit

The Montrose Historical & Telephone Pioneer Museum in Michigan didn’t start out with its main focus on telephones. In 1980, a group of local citizens founded the Montrose Area Historical Association that bought the former Slade School building and, after renovation, opened it in 1983 as the Montrose Historical Museum. In 1990, it moved into the former Century Phone building next day, and was renamed the Montrose Historical & Telephone Pioneer Museum.

So where did the telephones come from? The core collection belonged to Wyman Jennings, whose personal history explains his interest in phones. In 1939, he and a partner, James Langston, bought the local phone company for $280—the equivalent of about $6,476 today—quite a bargain but not surprising considering the U.S. was still in the Great Depression. The purchase included the company’s telephones poles, lines, and switchboards.

So where did the telephones come from? The core collection belonged to Wyman Jennings, whose personal history explains his interest in phones. In 1939, he and a partner, James Langston, bought the local phone company for $280—the equivalent of about $6,476 today—quite a bargain but not surprising considering the U.S. was still in the Great Depression. The purchase included the company’s telephones poles, lines, and switchboards.

Wyman and his partner renamed their newly acquired concern the Public Service Telephone Company. In the years that followed, Wyman was a busy fellow. An early member of the local voluntary fire department, he spent twenty-five years on the Montrose School Board, championed the creation of the Montrose’s Jennings Public Library, and helped finance the construction of a new chapel in the Montrose Cemetery.

He sold the Public Service Company to Century Phone in 1972 for $1 million, then used part of this fortune to help finance the move of the Montrose Historical Museum to its current site. Upon his passing in 1997, much of his fortune went to the Jennings Foundation, which funds the museum to this day.

He sold the Public Service Company to Century Phone in 1972 for $1 million, then used part of this fortune to help finance the move of the Montrose Historical Museum to its current site. Upon his passing in 1997, much of his fortune went to the Jennings Foundation, which funds the museum to this day.

The museum’s building doesn’t look large from the outside, but this is deceptive. It’s much bigger than you’d expect and jam-packed with telephones in every direction you look. Usually small museums like this one are self-guided, but on the day my friend and I visited, we received a guided tour. We started with Michigan’s first telephone, a Willard. Patented in 1879, this wall phone was powered by a person’s voice that triggered induction to transmit sound. The Willard phone was an improvement on the Scottish-born Alexander Graham Bell’s original patent, which was issued on March 7, 1876. Many disagree that Bell was the first to invent the telephone, but he had better lawyers than everyone else, so he was able to successfully defend his right to the patent.

Michigan’s first phone comes from the town of St. Ignace, which is located at the lower tip of Michigan’s upper peninsula at the Straights of Mackinaw. Here in 1884, Judge C.R. Brown in partnership with his son, George, decided to start a telephone exchange in town. Two previous attempts had failed, but they were certain the Willard phone would be perfect for the venture. The plan was to connect a phone from the Mackinaw Lumber Company store to the Bay View House with three way stations. The phone line would follow the bay, making its length about a two-mile semi-circle.

Michigan’s first phone comes from the town of St. Ignace, which is located at the lower tip of Michigan’s upper peninsula at the Straights of Mackinaw. Here in 1884, Judge C.R. Brown in partnership with his son, George, decided to start a telephone exchange in town. Two previous attempts had failed, but they were certain the Willard phone would be perfect for the venture. The plan was to connect a phone from the Mackinaw Lumber Company store to the Bay View House with three way stations. The phone line would follow the bay, making its length about a two-mile semi-circle.

Naming their new business the American Private Line Telephone Company, they planned to put thirty-eight phones in town providing the total cost for the Willard patent and all the equipment didn’t exceed $800, and that the monthly maintenance cost didn’t surpass $40. Phones would be rented out for $2 a month. (In those days companies owned their phones and leased or rented them to customers.) Willard phones cost the company $10 each. Lines stretching more than a mile weren’t guaranteed to work unless they were “very straight.” Phones at noisy businesses such as factories and mills were provided with bells.

Because early phones like the Willard had such limited distance, someone came up with the idea of giving them extra power to extend this. At first hand cranks were used, then phones were powered with batteries. The earliest of these were wet cells—that is, they had a liquid acid mixture to generate power. One of the best types of batteries in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were powered by Fuller bichromate cells, in which zinc was put into a bath of dichromate of soda of potassium, water, and sulfuric acid. The chemical reaction generated about 2.14 volts. This was far more power than induction alone could generate, allowing more distance between phones.

Because early phones like the Willard had such limited distance, someone came up with the idea of giving them extra power to extend this. At first hand cranks were used, then phones were powered with batteries. The earliest of these were wet cells—that is, they had a liquid acid mixture to generate power. One of the best types of batteries in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were powered by Fuller bichromate cells, in which zinc was put into a bath of dichromate of soda of potassium, water, and sulfuric acid. The chemical reaction generated about 2.14 volts. This was far more power than induction alone could generate, allowing more distance between phones.

Wet cell batteries had a habit of leaking acid, which often destroyed whatever it made contact with, but fortunately dry cell batteries—ones that used solid chemicals to generate power—soon replaced them. Around 1894, the Bell System began sending power through the telephone lines themselves, eliminating the need for phones to have their own batteries. Other phone companies followed suit, and to this day landlines still provide the power used to transmit sound.

The museum has a staggering number of novelty phones, including ones made to look like classic cars, planes, at least one designed to look like a helicopter. Many licensed phones are here too. These include Ernie the Keebler elf, Elvis, the starship Enterprise, and a Harley-Davidson motorcycle.

The museum has a staggering number of novelty phones, including ones made to look like classic cars, planes, at least one designed to look like a helicopter. Many licensed phones are here too. These include Ernie the Keebler elf, Elvis, the starship Enterprise, and a Harley-Davidson motorcycle.

The museum also has equipment and tools used by phone companies. In the earliest days, telephone wires on poles were insulated with wax, although one imagines it melted off on exceptionally hot days. Another piece of equipment you’ll see are insulators, devices that sat atop telephone poles to keep the wires from touching the wood and thus grounding out.

Usually made of porcelain or glass, there is a collection of insulators in the museum with a twist: they’re all fakes. Rare ones can fetch a decent price, especially those that are colored light green, purple, deep amber, or threadless ones produced between 1850 and 1865. The ones in the museum’s collection of fakes were subjected to radiation to alter their color to increase their value.

Usually made of porcelain or glass, there is a collection of insulators in the museum with a twist: they’re all fakes. Rare ones can fetch a decent price, especially those that are colored light green, purple, deep amber, or threadless ones produced between 1850 and 1865. The ones in the museum’s collection of fakes were subjected to radiation to alter their color to increase their value.

Until the 1970s and 1980s, most telephone systems needed switchboards to direct calls from point A to point B. One example that the museum possesses was the first on Hawaii’s O’ahu island. It was built by Western Electric around 1890 and used by Hawaii Telecom, which started in 1883 as the Mutual Telephone Company. This was founded by Archibald Scott Cleghorn, a Scottish businessman who went native and married into the Hawaiian royal family. One of his legitimate daughters, Princess Kaʻiulani, was heir-apparent to the Hawaiian throne, but she never sat on it. In 1893, when she wasn’t quite eighteen, a coup by foreigners overthrew the monarchy and replaced it with the Republic of Hawaii, which soon became a U.S. territory.

The last part of the guided tour took us to a room dedicated to the history of Montrose. Here there are, among other places, replicas of a bank, a hardware store, and a pharmacy. Many of these businesses were started by brothers Charles and Clarence Haight, who arrived in Montrose in 1895 but didn’t stay all that long. Clarence moved to Flint in 1899, and Charles to Grand Rapids in 1901. A museum information sign says, “No one knows why these hard working brothers left Montrose.”

The last part of the guided tour took us to a room dedicated to the history of Montrose. Here there are, among other places, replicas of a bank, a hardware store, and a pharmacy. Many of these businesses were started by brothers Charles and Clarence Haight, who arrived in Montrose in 1895 but didn’t stay all that long. Clarence moved to Flint in 1899, and Charles to Grand Rapids in 1901. A museum information sign says, “No one knows why these hard working brothers left Montrose.”

One exhibit in the local history room is filled with quilts. An information sign says that quilting became a fad in 1880s America. It’s at this time the Crazy quilt was invented, which consists of a patchwork of random colors and shapes, often taken from worn out clothes, blankets and other fabrics. Quilts were usually made from cotton and generally served the purpose of keeping their users warm.

Another exhibit is a collection of canning jars. In 1795, Napoleon Bonapart offered a prize of 12,000 fracs to anyone who found a way to preserve food for his men on the march. Nicolas Appert won in 1810 by developing a way to seal food in glass jars, the technique known today as canning. The modern type of canning jar, which has threads on its neck onto which one screwed a cap, was patented by John Landis Mason in 1858. The separate gasketed lid held on by threaded ring was patented by Alexander H. Kerr on May 10, 1910.

The most unusual collection at the museum consists of Vaseline glass, a type of transparent glassware that’s typically an ugly shade of yellow with a hint of green. I wouldn’t have paid attention to it had our guide not dimmed the lights and turned on a UV lightbulb, causing the collection to glow! So what’s the secret? It’s infused with uranium. I didn’t have a Geiger counter handy, but I was assured it doesn’t emit dangerous levels of radiation. I was also told it’s purely decorative—no one uses it as their dishes. As it turned out, the person who loaned this glassware to the museum was there that day, and she said she’d amassed had a much larger collection but had parted with most of it after moving into a smaller home.🕜

Another exhibit is a collection of canning jars. In 1795, Napoleon Bonapart offered a prize of 12,000 fracs to anyone who found a way to preserve food for his men on the march. Nicolas Appert won in 1810 by developing a way to seal food in glass jars, the technique known today as canning. The modern type of canning jar, which has threads on its neck onto which one screwed a cap, was patented by John Landis Mason in 1858. The separate gasketed lid held on by threaded ring was patented by Alexander H. Kerr on May 10, 1910.

The most unusual collection at the museum consists of Vaseline glass, a type of transparent glassware that’s typically an ugly shade of yellow with a hint of green. I wouldn’t have paid attention to it had our guide not dimmed the lights and turned on a UV lightbulb, causing the collection to glow! So what’s the secret? It’s infused with uranium. I didn’t have a Geiger counter handy, but I was assured it doesn’t emit dangerous levels of radiation. I was also told it’s purely decorative—no one uses it as their dishes. As it turned out, the person who loaned this glassware to the museum was there that day, and she said she’d amassed had a much larger collection but had parted with most of it after moving into a smaller home.🕜

Military Phone

Switchboard

Teletype Machine

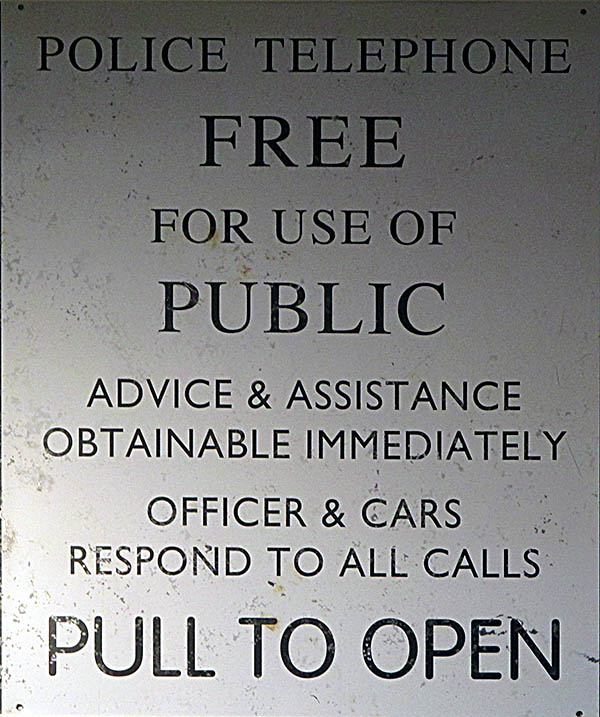

Plaque from a British police box. Or possibly stolen from the Doctor's TARDIS.

These fake telephone pole insulators were subjected to radiation to change their color.

Canning Exhibit

Vaseline Glass Under UV (Black) Light