Motts Military Museum

Museum Exterior

In the center is a U.S. deputy marshal's badge behind which is an authentic piece of barbed wire used in North Dakota.

Inside the Museum

EVA gloves used for space walks outside the space shuttles.

This portable organ was used during World War I for services by Chaplain Raymond Prior Sanford.

World War Medical Kit

World War I Veterinarian Tools

This toy made by O&M Hausse under the name Elastolin was brought home from Germany by William "Bumpy" Bletcher, who served on the USS Enterprise.

Replica of a Civil War underwater mine, then known as a torpedo.

Confederate Grave Marker

This Civil War bayonet was made into a sickle used for harvesting wheat.

Shells and balls used during the Civil War.

Civil War Binoculars

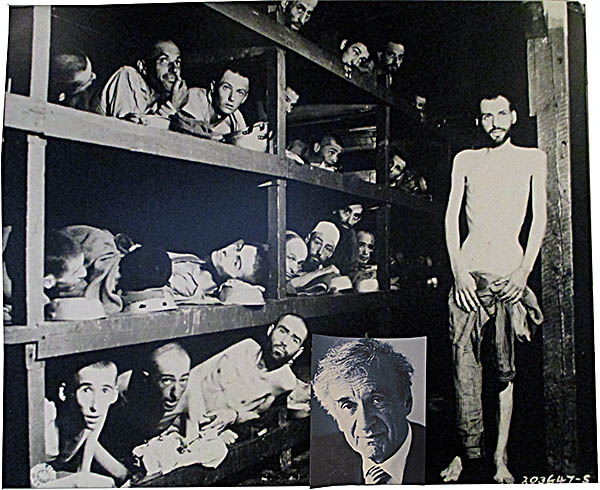

Russian Jews who died fighting the Nazis.

This photo by Sgt. Richard Kent was taken at Dachau. The insert is of one of the prisoners in the photo's background year later.

Colt M1911 Pistol used by Earl Beilhart during World War I.

Items from the 10th Mountain Division

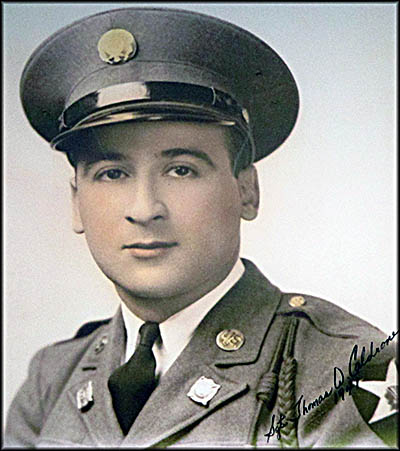

Sergeant Thomas W. Caldrone

Sally Durant Farmer's Uniform (reproduction)

MASH surgery from the Korean War.

Higgins Boat

Want to see George Washington’s hair? How about Lincoln’s? Or maybe you’d like to see a piece of cloth from the lining of President McKinley’s coffin? You find these somewhat morbid items and a whole lot more at Mott’s Military Museum in Groveport, Ohio. Washington’s hair, by the way, came from his adopted granddaughter, Eleanor Parke Custis, who gave it to Colonel Levin Powell. Lincoln’s hair was clipped in 1864 and given to one of his secretaries, Edward Duffield Neill. The piece of cloth from McKinley’s coffin didn’t really come from the coffin proper. Rather, it was from the roll of cloth used to line the coffin.

A museum staff member told me that its founder, Warren E. Motts, once housed his collection in his basement until his wife insisted he put it elsewhere, so he built this museum to display it. Even then, much of his collection is in storage because there’s just not enough room to display it all. Looking at the museum from the front, this doesn’t seem surprising, but it’s much bigger than it looks. I spent a good two hours going through it.

That the museum is jam-packed with historic artifacts primarily from the U.S. military is an understatement. If you are props master for a movie or television show looking for examples of authentic historic artifacts, this is the place for you. There is, for example, a badge for a deputy U.S. marshal in the Oklahoma Territory behind which is barbed wire from North Dakota.

On the day I visited, Mott himself and a curator were updating a display. They said they make it a point to label each item so visitor’s know what they’re looking at, and with one exception (it was some sort of radar control panel), that was true. Nearly everything in the museum is behind plexiglass, which was a bit frustrating for me because it prevented me from getting good photos of some of some of the objects mentioned in this travel log.

A museum staff member told me that its founder, Warren E. Motts, once housed his collection in his basement until his wife insisted he put it elsewhere, so he built this museum to display it. Even then, much of his collection is in storage because there’s just not enough room to display it all. Looking at the museum from the front, this doesn’t seem surprising, but it’s much bigger than it looks. I spent a good two hours going through it.

That the museum is jam-packed with historic artifacts primarily from the U.S. military is an understatement. If you are props master for a movie or television show looking for examples of authentic historic artifacts, this is the place for you. There is, for example, a badge for a deputy U.S. marshal in the Oklahoma Territory behind which is barbed wire from North Dakota.

On the day I visited, Mott himself and a curator were updating a display. They said they make it a point to label each item so visitor’s know what they’re looking at, and with one exception (it was some sort of radar control panel), that was true. Nearly everything in the museum is behind plexiglass, which was a bit frustrating for me because it prevented me from getting good photos of some of some of the objects mentioned in this travel log.

Although the museum’s primary purpose is to display items from or related to military history, it does veer off into other topics. There is an exhibit, for example, about the American Freedom Train, which traveled across the United States from April 1, 1775, to December 31, 1776. Its cars were filled with important items from U.S. history on display to those who boarded. This train is what made Warren Mott’s career. He was a professional photographer, and being the official one for this trip was quite the coup.

Another exhibit with a decidedly civilian purpose is the one that looks at the history of U.S. space travel. Here, among other things, you can see information and photos of John Glenn, a pair of space shuttle Extra Vehicular Activity (EVA) gloves, and a tire from the space shuttle Discovery used when it landed on February 11, 1994. This particular mission launched on February 3 and included the first Russian cosmonaut to be sent to space by the United States.

I’ve always joked that no self-respecting history museum doesn’t have at least one piano or organ (or both), but what I saw here surprised me. It was a portable field pump organ used by Raymond Prior Sandford during World War I. Despite having written a book about that conflict (Americans in a Splintering Europe), I didn’t know such a thing existed. Sandford, the senior chaplain at a fort in Le Harve, France, used it for services. These organs could be folded into a case carried by a single person and taken into the field.

Another exhibit with a decidedly civilian purpose is the one that looks at the history of U.S. space travel. Here, among other things, you can see information and photos of John Glenn, a pair of space shuttle Extra Vehicular Activity (EVA) gloves, and a tire from the space shuttle Discovery used when it landed on February 11, 1994. This particular mission launched on February 3 and included the first Russian cosmonaut to be sent to space by the United States.

I’ve always joked that no self-respecting history museum doesn’t have at least one piano or organ (or both), but what I saw here surprised me. It was a portable field pump organ used by Raymond Prior Sandford during World War I. Despite having written a book about that conflict (Americans in a Splintering Europe), I didn’t know such a thing existed. Sandford, the senior chaplain at a fort in Le Harve, France, used it for services. These organs could be folded into a case carried by a single person and taken into the field.

Another World War I artifact on display is a set of instruments used by American veterinarians. With the exception of the movie Warhorse, few movies and television shows that take place on the front during World War I show just how important animal power was. The vehicles of the day couldn’t get through the crater-cover, muddy places that one had to traverse to reach the front lines, so animal power—primarily horses and mules—was used for that. So many horses died during that war that the British and French completely exhausted their supply, forcing them to buy more from the United States, which had a surplus.

I initially thought that a German-made wood and papier-mâché Medieval castle on display was a piece of folk art made by a solider, but it turned out to be a toy made by O&M Hausse. This company, based in Ludwigsburg, Germany, had a line of military figures and related items that it sold under the name Elastolin. The toy on display was brought home by William “Bumpy” Bletcher, who served on the USS Enterprise during World War I.

The Civil War exhibit is filled with a wide variety of items. There is a Confederate battle flag that came from Georgia (not shown because I couldn’t get a decent photo), a Civil War underwater torpedo (mine) replica made by Harold Stone, Jr. that he based on an original drawing, and a Confederate cross marker, which I wondered if someone appropriated it from someone’s grave. A staff member assured me it was a surplus one that was never used. In the Bible, Isaiah 2:4 says, “And they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.” Well, someone took this literally and shaped a Civil War bayonet into a sickle used to harvest wheat.

I initially thought that a German-made wood and papier-mâché Medieval castle on display was a piece of folk art made by a solider, but it turned out to be a toy made by O&M Hausse. This company, based in Ludwigsburg, Germany, had a line of military figures and related items that it sold under the name Elastolin. The toy on display was brought home by William “Bumpy” Bletcher, who served on the USS Enterprise during World War I.

The Civil War exhibit is filled with a wide variety of items. There is a Confederate battle flag that came from Georgia (not shown because I couldn’t get a decent photo), a Civil War underwater torpedo (mine) replica made by Harold Stone, Jr. that he based on an original drawing, and a Confederate cross marker, which I wondered if someone appropriated it from someone’s grave. A staff member assured me it was a surplus one that was never used. In the Bible, Isaiah 2:4 says, “And they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.” Well, someone took this literally and shaped a Civil War bayonet into a sickle used to harvest wheat.

Scattered throughout the museum are personal recollections of American war experiences, sometimes told by a person’s son or daughter. Hebert Berstein from Brooklyn, New York, served in World War II as a platoon sergeant who was one of those who landed in Normandy on D-Day. After watching Private Ryan, his son, Paul, asked him how accurate the opening act was. “The sensation he recalled most vividly [wrote Paul] was the smell of thousands of fish rotting after being killed by the concussion of so many high explosives in the water. He never really cared for fish for as long as I knew him, and at that moment I suddenly realized why.”

After landing, Herbert was tasked with protecting the forward bases of P-47 fighter-bombers that were supporting Patton’s Third Army. He got his best meal in Europe from a French farmer “in exchange for K-rations, coffee, chocolate and cigarettes.” Although wounded by mortar fire in November 1944, he left the hospital prematurely just in time to participate in the brutal Battle of the Bulge, the last German offensive of the war.

He and other Jews in the unit celebrated Passover in Hermann Göring’s Veldenstein estate in Bavaria where he smoked one of Göring’s cigars. He helped to liberate several concentration camps, making him an eyewitness of the Holocaust. And while not all camps were death camps whose purpose was to exterminate Jews and other “undesirables,” they were horrid places to see nonetheless. Herbert achieved the rank of lieutenant before mustering out of the army.

After landing, Herbert was tasked with protecting the forward bases of P-47 fighter-bombers that were supporting Patton’s Third Army. He got his best meal in Europe from a French farmer “in exchange for K-rations, coffee, chocolate and cigarettes.” Although wounded by mortar fire in November 1944, he left the hospital prematurely just in time to participate in the brutal Battle of the Bulge, the last German offensive of the war.

He and other Jews in the unit celebrated Passover in Hermann Göring’s Veldenstein estate in Bavaria where he smoked one of Göring’s cigars. He helped to liberate several concentration camps, making him an eyewitness of the Holocaust. And while not all camps were death camps whose purpose was to exterminate Jews and other “undesirables,” they were horrid places to see nonetheless. Herbert achieved the rank of lieutenant before mustering out of the army.

The museum has an exhibit dedicated to the Holocaust and the liberation of the camps. One framed piece shows photos of Russian Jews who were killed fighting the Nazis. Another is a photo of Dachau taken by Sergeant Richard Kent of the U.S. Signal Corps Special Motion Picture Coverage Unit (SPECU) that shows prisoners in their barracks. The inset photo is of one of the prisoners in the original photo’s background as an older man.

Although the invasion of France is probably the most well-known event during World War II in Europe, a second front continued to be bloody: Italy. After its surrender in September 1943, the Germans continued to occupy the county, and they were especially hard to dislodge from the mountains where warfare often included moving using skis. To remove the Germans, the U.S. Army sent in the 10th Mountain Division. Hard fighting ensued when it took Campiano-Mancinella Ridge (Riva Ridge) as a precursor to attacking Mount Belvedere. During its six month tour in Italy, 1,000 of its 20,000 men died, and another 3,900 were wounded.

There is an exhibit about American Prisoners of War that highlights the experiences of several Americans during different wars. Sallie Durant Farmer was a U.S. nurse in the Philippines when the Japanese invaded the islands. She evacuated from the Bataan Peninsula to the well-fortified Corregidor Island. Here a tailor named Mr. Cheng made her a pair of coveralls and two khaki shirts, the only clothes (in addition to some skirts) she’d have for the next few years. When Corregidor Island fell on May 6, 1942, she became a POW.

Although the invasion of France is probably the most well-known event during World War II in Europe, a second front continued to be bloody: Italy. After its surrender in September 1943, the Germans continued to occupy the county, and they were especially hard to dislodge from the mountains where warfare often included moving using skis. To remove the Germans, the U.S. Army sent in the 10th Mountain Division. Hard fighting ensued when it took Campiano-Mancinella Ridge (Riva Ridge) as a precursor to attacking Mount Belvedere. During its six month tour in Italy, 1,000 of its 20,000 men died, and another 3,900 were wounded.

There is an exhibit about American Prisoners of War that highlights the experiences of several Americans during different wars. Sallie Durant Farmer was a U.S. nurse in the Philippines when the Japanese invaded the islands. She evacuated from the Bataan Peninsula to the well-fortified Corregidor Island. Here a tailor named Mr. Cheng made her a pair of coveralls and two khaki shirts, the only clothes (in addition to some skirts) she’d have for the next few years. When Corregidor Island fell on May 6, 1942, she became a POW.

The Japanese moved her to the Santo Tomas Internment Camp in Manila in July 1942 where she worked in its hospital. Here she wore a blouse and skirt in the day and her overalls at night, which protected her from lizards and mosquitoes. When her American shoes wore out, she switched to Filipino clogs. Given access to string, she knitted undergarments and socks using bamboo needles. She recalled that soap was rare and toilet paper rationed. Tooth brushes were made from pig bristles attached to bamboo and toothpaste from soda and salt.

Sergeant Thomas W. Caldrone was captured during World War II in the European Theater during the Battle of the Bulge. During his time as a POW, he was moved into three different prisoner of war camps (stalags). One German guard, realizing his country had lost the war and not keen on being captured by the approaching Russians, offered to help Caldrone and three others escape in exchange for getting him to America. They agreed, but the German SS caught them, then sent them to Dachau.

At Dachau a woman who spoke perfect English told them she was from Brooklyn and was here because she’d married a German solider. She offered to help them escape, which they accepted. They ran into the woods while she distracted the guards. From here they made their way to a nearby village where they headed to a certain house at which they’d receive fake papers. Before reaching it, fighting broke out between the Germans and Americans, and they thought it prudent to claim illness and checked into a German hospital for protection. During the fighting a German officer tried to surrender to Caldrone, but he refused to accept it. The arrival of Sherman tank in front of the hospital the next morning indicated they’d been liberated.

Two carvings made by Sergeant Carl Cossin show what life was like for him after being taken prisoner during the Korean War. He was one of the unfortunate American POWs who participated in what is today known as the Tiger Death March, so called because the sadistic Korean officer in charge, Major Chong Myong Sil, was nicknamed by the prisoners as the Tiger. Although the march began on October 8, 1950, the Tiger didn’t take command until October 31, and that’s when things got a whole lot worse. On November 1, he shot Lieutenant Cordus H. Thorton in the head, following that up with ordering the machine-gunning of sixteen wounded men couldn’t walk. By the time the Americans, a British marine and seventy-nine civilians reached a POW camp near Siberia, ninety-two American soldiers had died. At the camp itself the prisoners were plagued by lice, worms, and a terrible stench caused by “excrement from vermin.”

Outside and behind the museum building you can see a treasure trove of tanks, artillery, helicopters, one jet, one plane, and a Higgins Boat, few of which exist today. Designed by Andrew Jackson Higgins from New Orleans, the Higgins Boat was an armed troop carrier that could land directly on beaches, allowing navies to avoid the costly business of taking a port. Made of metal (unlike PT boats, which were wood), they were armed and large. They were used primarily in the Pacific to land on Japanese-occupied islands.🕜

Sergeant Thomas W. Caldrone was captured during World War II in the European Theater during the Battle of the Bulge. During his time as a POW, he was moved into three different prisoner of war camps (stalags). One German guard, realizing his country had lost the war and not keen on being captured by the approaching Russians, offered to help Caldrone and three others escape in exchange for getting him to America. They agreed, but the German SS caught them, then sent them to Dachau.

At Dachau a woman who spoke perfect English told them she was from Brooklyn and was here because she’d married a German solider. She offered to help them escape, which they accepted. They ran into the woods while she distracted the guards. From here they made their way to a nearby village where they headed to a certain house at which they’d receive fake papers. Before reaching it, fighting broke out between the Germans and Americans, and they thought it prudent to claim illness and checked into a German hospital for protection. During the fighting a German officer tried to surrender to Caldrone, but he refused to accept it. The arrival of Sherman tank in front of the hospital the next morning indicated they’d been liberated.

Two carvings made by Sergeant Carl Cossin show what life was like for him after being taken prisoner during the Korean War. He was one of the unfortunate American POWs who participated in what is today known as the Tiger Death March, so called because the sadistic Korean officer in charge, Major Chong Myong Sil, was nicknamed by the prisoners as the Tiger. Although the march began on October 8, 1950, the Tiger didn’t take command until October 31, and that’s when things got a whole lot worse. On November 1, he shot Lieutenant Cordus H. Thorton in the head, following that up with ordering the machine-gunning of sixteen wounded men couldn’t walk. By the time the Americans, a British marine and seventy-nine civilians reached a POW camp near Siberia, ninety-two American soldiers had died. At the camp itself the prisoners were plagued by lice, worms, and a terrible stench caused by “excrement from vermin.”

Outside and behind the museum building you can see a treasure trove of tanks, artillery, helicopters, one jet, one plane, and a Higgins Boat, few of which exist today. Designed by Andrew Jackson Higgins from New Orleans, the Higgins Boat was an armed troop carrier that could land directly on beaches, allowing navies to avoid the costly business of taking a port. Made of metal (unlike PT boats, which were wood), they were armed and large. They were used primarily in the Pacific to land on Japanese-occupied islands.🕜