MR. FRANKLIN’S PRIVATEER

Copyright © 2012 by Mark Strecker.

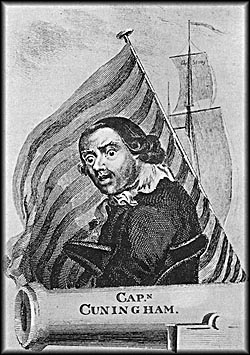

Captain Gustavus Conynhgam, Continental Navy

Engraving contemporary to the American Revolution, based on “the Original Sketch which was taken by an Artist of Eminence, and stuck up in the English Coffee House at Dunkirk”.

U.S. Naval Historical Center

Engraving contemporary to the American Revolution, based on “the Original Sketch which was taken by an Artist of Eminence, and stuck up in the English Coffee House at Dunkirk”.

U.S. Naval Historical Center

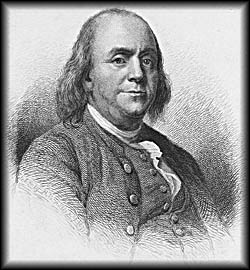

Benjamin Franklin

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Gustavus Conyngham’s career as a privateer captain during the American Revolution reads like an adventure novel, complete with setbacks and bad luck. This forgotten naval hero lived in Ireland but, after moving to Philadelphia, became a fiercely patriotic American. Virtually no documents exist that describe his life in Ireland, although we do know he came from the Protestant gentry class. The mass of records about his activities during the war provide ample details about his actions but offer little in the way of information describing his personality.

Conyngham initially began his war career as the captain of the merchant brig Charming Peggy, a vessel he took to Holland for the procurement of munitions. When he arrived, the Dutch refused to allow him to dock. He moored behind the island of Terheide and waited for two Dutch supply ships to bring him his goods. Before they arrived, a gale whipped up the sea and forced the Charming Peggy to move to Nieuport, where she entered a canal.

Four days later the supply vessels caught up, but a contrary wind and high tide knocked Charming Peggy onto a sandbar, where she became stuck. One of Conyngham’s men deserted and reported his position to the British consulate in Ostend. Although he managed to free his brig from its canal prison, the British caught him before he could make an escape to sea. They placed a guard on board with plans to take he and his crew into custody when they could arrange it, but before that happened, Conyngham and his crew overpowered the sentries and retook control.

Contrary winds kept Charming Peggy from making her way out. Rather than risk capture again, Conyngham and his crew abandoned ship and made their way into Holland. From there Conyngham traveled to France to make contact with Americans there in hopes of becoming gainfully employed in the American cause. He soon got his chance. A man named William Hodges purchased a vessel to serve as a privateer against British shipping in European waters and made Conyngham her captain.

Hodges took his orders from the American Commissioners, a group of Americans living in France composed of Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, and Arthur Lee. They had the task of clandestinely commissioning American privateers to sail European waters with the mission of capturing British merchant ships and bringing them into French ports. By doing so the American planners hoped to spark a war between the two great powers. Franklin took the most interest in Conyngham’s privateer career. He issued Conyngham his first commission, which gave him the rank of captain in the newly created Continental Navy. It also served as a letter of marque, giving him the legal authority to capture British merchant ships without the fear of being arrested for piracy.

His new vessel, the twelve-gun cutter Surprize, fitted out in Dunkirk’s harbor, the worst French port from which an American privateer could possibly launch an attack on British shipping. The 1763 Treaty of Paris forbade the French from arming it with defenses, kept it open to all British shipping, and created the position of a British inspector to ensure the French complied. Nonetheless, the Surprize departed on May 1, 1777. Conyngham disguised her as a smuggler but the ruse fooled no one: the British already knew her true purpose.

Three days later the Surprize took the British packet Harwick (a mail and general transport vessel) and, the next, another packet, the brig Joseph. Conyngham then did something either extraordinarily stupid or incredibly bold, depending on one’s point of view: he returned to Dunkirk with both vessels in tow! Before the British could mount protests and express outrage, Hodges took all the captured mail to Franklin and the other commissioners, who found this intelligence invaluable. The British protested vehemently. The French quickly seized the two packets and threw Conyngham and his crew into jail, confiscating Conyngham’s commission and sending it to Versailles, where it promptly disappeared. They released them in June after restoring the packets to the British in an effort to quiet them down.

Hodges sold the Surprize. He then bought a twenty-five percent share in a new vessel, the 130-ton cutter Revenge, in partnership with Conyngham’s recently arrived cousin, David Conyngham, and the Continental Congress. The Americans claimed they planned to use her for smuggling. When told this by French authorities, the British ambassador, Lord Stormont, cynically noted that smugglers do not arm themselves with eighteen guns. The British no intention of allowing the Revenge to leave port unless the French to obtained a money security from her owners to assure them that she would not attack any British vessels, something Hodges insisted would ruin him. French officials wrote letter after letter to one another denying they knew anything about the Revenge’s use as a privateer. The British, unperturbed, sent a flotilla of five ships to guard the harbor to ensure the Revenge never emerged. If she did, they would burn her the moment she cleared the harbor.

Upon learning of this plan, the French “inspected” the Revenge twice and found neither arms nor any Frenchmen among the crew, a convenient lie. The French commandant at Dunkirk, M. de Guichard, slyly reported to Comte de Vergennes, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, that “if, in the country or the coast, or in the dunes during the night any Frenchman has been hidden, who may have found means of joining the smuggler, that is impossible for me to anticipate or prevent.” When Guichard received orders to stop Conyngham from leaving, he refused, arguing that since Dunkirk had no arms of any sort and that the Revenge did, he could do nothing to stop her.

She departed on July 17, 1777, with no molestation from the Royal Navy because she had supposedly disarmed. Although the British knew otherwise for certain, they did not care because the Revenge’s owners had provided them with the demanded security. A few days later she secretly arrived in another French port in which she picked up arms, acquired supplies, and signed up French crewmen. Although accounts differ, by the time she headed back to sea, she had between fourteen and twenty guns and a crew of about seventy men.

Four days later the supply vessels caught up, but a contrary wind and high tide knocked Charming Peggy onto a sandbar, where she became stuck. One of Conyngham’s men deserted and reported his position to the British consulate in Ostend. Although he managed to free his brig from its canal prison, the British caught him before he could make an escape to sea. They placed a guard on board with plans to take he and his crew into custody when they could arrange it, but before that happened, Conyngham and his crew overpowered the sentries and retook control.

Contrary winds kept Charming Peggy from making her way out. Rather than risk capture again, Conyngham and his crew abandoned ship and made their way into Holland. From there Conyngham traveled to France to make contact with Americans there in hopes of becoming gainfully employed in the American cause. He soon got his chance. A man named William Hodges purchased a vessel to serve as a privateer against British shipping in European waters and made Conyngham her captain.

Hodges took his orders from the American Commissioners, a group of Americans living in France composed of Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, and Arthur Lee. They had the task of clandestinely commissioning American privateers to sail European waters with the mission of capturing British merchant ships and bringing them into French ports. By doing so the American planners hoped to spark a war between the two great powers. Franklin took the most interest in Conyngham’s privateer career. He issued Conyngham his first commission, which gave him the rank of captain in the newly created Continental Navy. It also served as a letter of marque, giving him the legal authority to capture British merchant ships without the fear of being arrested for piracy.

His new vessel, the twelve-gun cutter Surprize, fitted out in Dunkirk’s harbor, the worst French port from which an American privateer could possibly launch an attack on British shipping. The 1763 Treaty of Paris forbade the French from arming it with defenses, kept it open to all British shipping, and created the position of a British inspector to ensure the French complied. Nonetheless, the Surprize departed on May 1, 1777. Conyngham disguised her as a smuggler but the ruse fooled no one: the British already knew her true purpose.

Three days later the Surprize took the British packet Harwick (a mail and general transport vessel) and, the next, another packet, the brig Joseph. Conyngham then did something either extraordinarily stupid or incredibly bold, depending on one’s point of view: he returned to Dunkirk with both vessels in tow! Before the British could mount protests and express outrage, Hodges took all the captured mail to Franklin and the other commissioners, who found this intelligence invaluable. The British protested vehemently. The French quickly seized the two packets and threw Conyngham and his crew into jail, confiscating Conyngham’s commission and sending it to Versailles, where it promptly disappeared. They released them in June after restoring the packets to the British in an effort to quiet them down.

Hodges sold the Surprize. He then bought a twenty-five percent share in a new vessel, the 130-ton cutter Revenge, in partnership with Conyngham’s recently arrived cousin, David Conyngham, and the Continental Congress. The Americans claimed they planned to use her for smuggling. When told this by French authorities, the British ambassador, Lord Stormont, cynically noted that smugglers do not arm themselves with eighteen guns. The British no intention of allowing the Revenge to leave port unless the French to obtained a money security from her owners to assure them that she would not attack any British vessels, something Hodges insisted would ruin him. French officials wrote letter after letter to one another denying they knew anything about the Revenge’s use as a privateer. The British, unperturbed, sent a flotilla of five ships to guard the harbor to ensure the Revenge never emerged. If she did, they would burn her the moment she cleared the harbor.

Upon learning of this plan, the French “inspected” the Revenge twice and found neither arms nor any Frenchmen among the crew, a convenient lie. The French commandant at Dunkirk, M. de Guichard, slyly reported to Comte de Vergennes, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, that “if, in the country or the coast, or in the dunes during the night any Frenchman has been hidden, who may have found means of joining the smuggler, that is impossible for me to anticipate or prevent.” When Guichard received orders to stop Conyngham from leaving, he refused, arguing that since Dunkirk had no arms of any sort and that the Revenge did, he could do nothing to stop her.

She departed on July 17, 1777, with no molestation from the Royal Navy because she had supposedly disarmed. Although the British knew otherwise for certain, they did not care because the Revenge’s owners had provided them with the demanded security. A few days later she secretly arrived in another French port in which she picked up arms, acquired supplies, and signed up French crewmen. Although accounts differ, by the time she headed back to sea, she had between fourteen and twenty guns and a crew of about seventy men.

The Phoenix and the Rose Engaged by the Enemy's Fire ships And Galleys on the 16 August, 1776

“Engraved from the Original Picture by S. Serres from a Sketch of Sir James Wallace”

Library of Congress

“Engraved from the Original Picture by S. Serres from a Sketch of Sir James Wallace”

Library of Congress

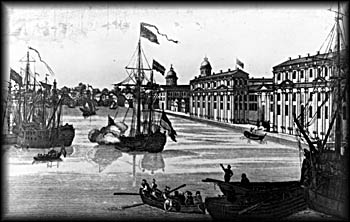

Philadelphie - la ville capitale de Pensylvanie province Nord-Americaine William Penn, à qui Charles II Roi d'Angleterre donna cette province entiére la planta en 1682 ...

Présentement chez Basset rue Saint Jacques au coin de celle des Mathurins, Tient Fabrique de Papiers. Library of Congress.

Présentement chez Basset rue Saint Jacques au coin de celle des Mathurins, Tient Fabrique de Papiers. Library of Congress.

Alexander Hamilton

Library of Congress.

Library of Congress.

Officially, Conyngham received orders from the Commissioners to sail directly to America and not to attack any ships unless in self-defense. Unofficially, the Commissioner’s secretary, William Carmichael, told him to wreak havoc upon British shipping in European waters with the caveat he avoid using Dunkirk for any reason. Conyngham, in his sparse and sometimes incomprehensible account, wrote that after leaving, the Revenge went east, then northeast into the Baltic, North and Irish Seas. There she captured and burned or ransomed several prizes. One of these, the brig Northampton, fell back into British hands. One of her prize crew admitted he and the others had come from a privateer under Conyngham’s command. So much for French assurances he meant no harm to British shipping.

The British protested to the French government, threatening to break off diplomatic relations and to destroy the French fishing fleet at the Grand Banks of Newfoundland if they did not do something about this situation immediately. Vergennes blamed the Admiralty of Dunkirk, saying it deceived him and he knew nothing of this. The French government arrested Hodges and threw him into the notorious Bastille to show its repentance. (Hodges would not remain there long; after his release he went to Spain to continue working with Conyngham.)

As the French tried to repair the diplomatic damage Conyngham had caused, he continued to capture British vessels at an unbelievable rate. In Spain, the British consul in Corunna, Herman Katencamp, complained Spanish harbor officials allowed Conyngham to bring his prizes there. When Katencamp finally got Corunna’s captain general to ban Conyngham from port, he fumed when the privateer captain boldly docked there anyway and proceeded to unrig his ship for refitting! Well, the king’s pilot replied, Conyngham’s vessel had become unfit for sea, and international law compelled him to allow a distressed ship to effect repairs.

By this time Conyngham had accomplished what he had set out to do. British shipping quaked in fear. Franklin wrote to the Committee of Foreign Affairs that Conyngham’s attacks had raised the insurance rates for packets traveling from Dover to Calais by ten percent. Silas Deane penned that Conyngham’s “expeditions caused a great sensation to the British Commerce; and for the first time since Britain was a maritime power, the River Thames and other of its ports were crowded with French and other ships taking in Freight, in order to avoid the risk of having British property captured.” Incensed, a group of English merchants purchased space in a variety of newspapers with an advertisement warning British merchant ships to watch out for American privateers, who, as the ad put it, would “prove ruinous to the commercial interests of this Kingdom.” It asked if someone in power would please do something about the situation.

Conyngham’s good fortune ran out when the true nature of privateer crews got the best of him. Although he had purely patriotic motives for attacking British shipping, his crew did not. Privateer crewmen joined for the money and nothing else. Conyngham’s crew therefore threatened to mutiny on two occasions. The first came when the Revenge’s crew spied the brig Grasiosa, an English-insured vessel known to have a cargo worth about £75,000. Conyngham reluctantly agreed to take her. When his prize crew took her to Bilboa, Spanish officials refused to allow her disposal. He went to the Court of St. Sebastians to secure her release for condemnation without success. The Spanish freed her and forced Conyngham to pay for damages. Not surprisingly, most of his crew abandoned him then and there since they would receive no pay.

From this point on Conyngham had trouble keeping a crew for more than one cruise at a time for lack of money. He could only offer payment based on prize money, but the British recaptured most of his prizes before they made it into a safe port for disposal, and when they did, he often found his agents unwilling to pay him in a prompt manner.

On May 31, 1778, the Revenge came across a Swedish brig named Henrica Sophia, a vessel carrying British goods but not under any sort of British command or ownership. Several of Conyngham’s crew knew that she carried a valuable cargo of dry goods. Conyngham realized if he refused to attack, his crew would probably mutiny. He conceded to their demand, but insisted those involved sign a deposition taking full responsibility for their actions. They agreed. After her capture, a prize crew headed to Boston but a British ship liberated her before she made it into port. The Swedish government, understandably livid, had no diplomatic relations with America, so it protested the capture to the French. The French replied that they could do nothing because they had no jurisdiction over America or Americans. The British used the incident to pressure the Spanish government into permanently barring Conyngham and his prizes from their ports.

This forced him to take the Revenge to the West Indies, where she had some success before the Marine Committee (the body that oversaw all American naval activities) ordered her to come to Philadelphia in early January 1779. There Congress looked into Conyngham’s actions to determine the legality of his taking of the Henrica Sophia. Because of the deposition he possessed, it decided not to charge him, but did order the auction of the Revenge to wash its hands of the controversial vessel. By this time Conyngham had captured or destroyed sixty vessels in under two years of cruising.

The British protested to the French government, threatening to break off diplomatic relations and to destroy the French fishing fleet at the Grand Banks of Newfoundland if they did not do something about this situation immediately. Vergennes blamed the Admiralty of Dunkirk, saying it deceived him and he knew nothing of this. The French government arrested Hodges and threw him into the notorious Bastille to show its repentance. (Hodges would not remain there long; after his release he went to Spain to continue working with Conyngham.)

As the French tried to repair the diplomatic damage Conyngham had caused, he continued to capture British vessels at an unbelievable rate. In Spain, the British consul in Corunna, Herman Katencamp, complained Spanish harbor officials allowed Conyngham to bring his prizes there. When Katencamp finally got Corunna’s captain general to ban Conyngham from port, he fumed when the privateer captain boldly docked there anyway and proceeded to unrig his ship for refitting! Well, the king’s pilot replied, Conyngham’s vessel had become unfit for sea, and international law compelled him to allow a distressed ship to effect repairs.

By this time Conyngham had accomplished what he had set out to do. British shipping quaked in fear. Franklin wrote to the Committee of Foreign Affairs that Conyngham’s attacks had raised the insurance rates for packets traveling from Dover to Calais by ten percent. Silas Deane penned that Conyngham’s “expeditions caused a great sensation to the British Commerce; and for the first time since Britain was a maritime power, the River Thames and other of its ports were crowded with French and other ships taking in Freight, in order to avoid the risk of having British property captured.” Incensed, a group of English merchants purchased space in a variety of newspapers with an advertisement warning British merchant ships to watch out for American privateers, who, as the ad put it, would “prove ruinous to the commercial interests of this Kingdom.” It asked if someone in power would please do something about the situation.

Conyngham’s good fortune ran out when the true nature of privateer crews got the best of him. Although he had purely patriotic motives for attacking British shipping, his crew did not. Privateer crewmen joined for the money and nothing else. Conyngham’s crew therefore threatened to mutiny on two occasions. The first came when the Revenge’s crew spied the brig Grasiosa, an English-insured vessel known to have a cargo worth about £75,000. Conyngham reluctantly agreed to take her. When his prize crew took her to Bilboa, Spanish officials refused to allow her disposal. He went to the Court of St. Sebastians to secure her release for condemnation without success. The Spanish freed her and forced Conyngham to pay for damages. Not surprisingly, most of his crew abandoned him then and there since they would receive no pay.

From this point on Conyngham had trouble keeping a crew for more than one cruise at a time for lack of money. He could only offer payment based on prize money, but the British recaptured most of his prizes before they made it into a safe port for disposal, and when they did, he often found his agents unwilling to pay him in a prompt manner.

On May 31, 1778, the Revenge came across a Swedish brig named Henrica Sophia, a vessel carrying British goods but not under any sort of British command or ownership. Several of Conyngham’s crew knew that she carried a valuable cargo of dry goods. Conyngham realized if he refused to attack, his crew would probably mutiny. He conceded to their demand, but insisted those involved sign a deposition taking full responsibility for their actions. They agreed. After her capture, a prize crew headed to Boston but a British ship liberated her before she made it into port. The Swedish government, understandably livid, had no diplomatic relations with America, so it protested the capture to the French. The French replied that they could do nothing because they had no jurisdiction over America or Americans. The British used the incident to pressure the Spanish government into permanently barring Conyngham and his prizes from their ports.

This forced him to take the Revenge to the West Indies, where she had some success before the Marine Committee (the body that oversaw all American naval activities) ordered her to come to Philadelphia in early January 1779. There Congress looked into Conyngham’s actions to determine the legality of his taking of the Henrica Sophia. Because of the deposition he possessed, it decided not to charge him, but did order the auction of the Revenge to wash its hands of the controversial vessel. By this time Conyngham had captured or destroyed sixty vessels in under two years of cruising.

The Revenge’s new owners offered to retain Conyngham as her captain if he so desired. After getting assurances from the Marine Committee he would retain his rank in the Navy if he did, he agreed, using his second commission to keep the cruise legal. He sailed north and, on April 27, engaged the British warship Gallatea, which captured him. She took him and his crew to the notorious fleet of prison ships in New York City. There his jailors threw him into solitary confinement and gave him only water, although he did no go without sustenance altogether as prisoners in nearby cells offered him some small morsels of food.

The citizens of Philadelphia put together a petition asking Congress to do something about his treatment, as did his wife, Anne. Congress wrote to the British admiral in charge of the prison ship fleet in New York, Sir George Collier, warning him it would retaliate if he did not treat his prisoners better. Collier replied he had no inclination to do anything British subjects demanded, particularly when they employed such an uncivil tone. The Marine Commission also wrote to Colonel John Beatty and warned him if he did not treat Conyngham better, the Commission would handle a British officer the same way; when Beatty refused, they wrote another letter to him informing him they had retaliated using an officer named Lieutenant Hele.

On the day Conyngham’s jailors released him from his cell, they placed him in a hangman’s cart to give him a fright, then took him to a waiting ship that transported him to England for trial. He arrived at Falmouth on July 7. Authorities took him to Pendennis Castle where they threw him in a dungeon for forty-two days because he had committed some minor infraction against the rules. They transferred him to Plymouth and put in him in Old Mill Prison in August, where he would stand trial for treason. Until a judge heard his case, he had to stay apart from the rest of the prisoners, forcing him to spend seven nights in an unpleasant place called the “black hole.”

Benjamin Franklin started his own campaign to get the British to treat Conyngham as a prisoner of war and not a common criminal. To that end, he wrote to a Mr. Diggs, his agent in London (who also served Britain as a spy and embezzled most of the money Franklin sent him), to go to Conyngham and provide him with whatever he needed. The demands put on the British government worked: Conyngham, who had thus far remained in irons, lost those and received the same freedoms as other American prisoners.

With his movements no longer restricted within the prison itself, he promptly made several attempts to escape, one of which succeeded. He and fifty-three fellow Americans tunneled out. Once free, he made his way to London where he contacted Mr. Diggs, who, despite his duplicity, helped him escape. Conyngham and six others took a boat to France. From there he went to Holland, then back to France, by then a much safer refuge. Franklin sent Conyngham some money, warning, “You will be as frugal as possible, money being scarce with me, and the calls upon me abundant.”

Conyngham sailed with John Paul Jones for a brief time, but neither he nor Jones left any record of this period. Thereafter Conyngham took command another privateer, but this cruise resulted in his recapture. He wound back in Old Mill Prison. Here he languished (and his health decayed) until July 1781, when Franklin secured his release. Free, Conyngham left for France where he met his waiting wife. Despite the presumably happy reunion, he felt it his duty to go back to sea once more. He helped to outfit a new ship, the Layona, but before she launched, the war ended. He returned home as a war hero.

His story has a regrettable ending. He tried in vain to receive his due pension as a captain in the Continental Navy, but Congress insisted that without his original commission, it could do nothing. It set up a committee over the matter. Despite the fact Franklin, an ailing old man by this time, wrote to that body verifying that he had given Conyngham the said commission, the Committee of Congress on the Conyngham Memorial decided in 1784 the missing commission only gave him a temporary rank of captain. He would receive no pension.

Hamilton, in his capacity as Secretary of the Treasury, pledged to bring the matter before Congress, but this went nowhere. Conyngham traveled to France twice looking for his lost commission, but it never appeared in his lifetime. It finally resurfaced in the early twentieth century as an item in a catalogue of a print-seller in Paris. It showed he had indeed possessed the rank and commission he had claimed. The very government he had fought so hard for had betrayed him; had it done the right thing, he would have received his well deserved pension.🕜

The citizens of Philadelphia put together a petition asking Congress to do something about his treatment, as did his wife, Anne. Congress wrote to the British admiral in charge of the prison ship fleet in New York, Sir George Collier, warning him it would retaliate if he did not treat his prisoners better. Collier replied he had no inclination to do anything British subjects demanded, particularly when they employed such an uncivil tone. The Marine Commission also wrote to Colonel John Beatty and warned him if he did not treat Conyngham better, the Commission would handle a British officer the same way; when Beatty refused, they wrote another letter to him informing him they had retaliated using an officer named Lieutenant Hele.

On the day Conyngham’s jailors released him from his cell, they placed him in a hangman’s cart to give him a fright, then took him to a waiting ship that transported him to England for trial. He arrived at Falmouth on July 7. Authorities took him to Pendennis Castle where they threw him in a dungeon for forty-two days because he had committed some minor infraction against the rules. They transferred him to Plymouth and put in him in Old Mill Prison in August, where he would stand trial for treason. Until a judge heard his case, he had to stay apart from the rest of the prisoners, forcing him to spend seven nights in an unpleasant place called the “black hole.”

Benjamin Franklin started his own campaign to get the British to treat Conyngham as a prisoner of war and not a common criminal. To that end, he wrote to a Mr. Diggs, his agent in London (who also served Britain as a spy and embezzled most of the money Franklin sent him), to go to Conyngham and provide him with whatever he needed. The demands put on the British government worked: Conyngham, who had thus far remained in irons, lost those and received the same freedoms as other American prisoners.

With his movements no longer restricted within the prison itself, he promptly made several attempts to escape, one of which succeeded. He and fifty-three fellow Americans tunneled out. Once free, he made his way to London where he contacted Mr. Diggs, who, despite his duplicity, helped him escape. Conyngham and six others took a boat to France. From there he went to Holland, then back to France, by then a much safer refuge. Franklin sent Conyngham some money, warning, “You will be as frugal as possible, money being scarce with me, and the calls upon me abundant.”

Conyngham sailed with John Paul Jones for a brief time, but neither he nor Jones left any record of this period. Thereafter Conyngham took command another privateer, but this cruise resulted in his recapture. He wound back in Old Mill Prison. Here he languished (and his health decayed) until July 1781, when Franklin secured his release. Free, Conyngham left for France where he met his waiting wife. Despite the presumably happy reunion, he felt it his duty to go back to sea once more. He helped to outfit a new ship, the Layona, but before she launched, the war ended. He returned home as a war hero.

His story has a regrettable ending. He tried in vain to receive his due pension as a captain in the Continental Navy, but Congress insisted that without his original commission, it could do nothing. It set up a committee over the matter. Despite the fact Franklin, an ailing old man by this time, wrote to that body verifying that he had given Conyngham the said commission, the Committee of Congress on the Conyngham Memorial decided in 1784 the missing commission only gave him a temporary rank of captain. He would receive no pension.

Hamilton, in his capacity as Secretary of the Treasury, pledged to bring the matter before Congress, but this went nowhere. Conyngham traveled to France twice looking for his lost commission, but it never appeared in his lifetime. It finally resurfaced in the early twentieth century as an item in a catalogue of a print-seller in Paris. It showed he had indeed possessed the rank and commission he had claimed. The very government he had fought so hard for had betrayed him; had it done the right thing, he would have received his well deserved pension.🕜