National Great Blacks in Wax Museum

National Blacks in Wax Museum

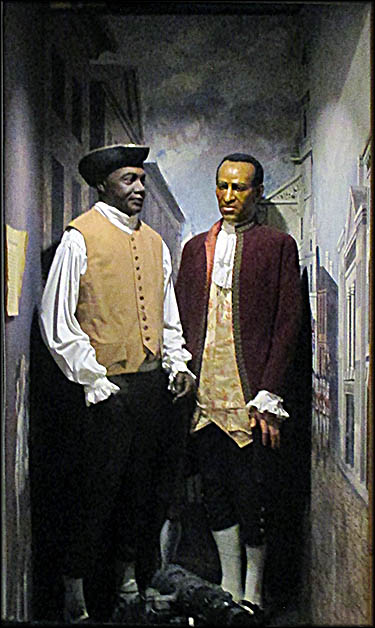

African Americans were prominent and quite important during the Colonial Era and the American Revolution.

Abolition and Women’s Rights

There is nothing I have visited quite like the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum, which is located in the heart of Baltimore. As its name implies, this is a wax museum. Art its figures are not, but they serve their purpose to show history in the third dimension. And they are far more real to one of the museum’s biggest target audiences, children, than to most adults.

Doctors Elmer and Joanne Martin opened this museum on Saratoga Street in 1983 with the objectives, according to the museum’s website, “to stimulate an interest in African American history by revealing the little-known, often-neglected facts of history, to use great leaders as role models to motivate youth to achieve, to improve race relations by dispelling myths of racial inferiority and superiority, [and] to support and work in conjunction with other nonprofit, charitable organizations seeking to improve the social and economic status of African Americans.” In the first two years they had 2,000 students visit. With so much traffic, by 1985 this former storefront could no longer easily accommodate so many. With the help of a $100,000 state grant and $100,000 in matched funds raised via donations, the museum moved into a former firehouse on East North Avenue. It is currently looking to relocate and expand once more.

Doctors Elmer and Joanne Martin opened this museum on Saratoga Street in 1983 with the objectives, according to the museum’s website, “to stimulate an interest in African American history by revealing the little-known, often-neglected facts of history, to use great leaders as role models to motivate youth to achieve, to improve race relations by dispelling myths of racial inferiority and superiority, [and] to support and work in conjunction with other nonprofit, charitable organizations seeking to improve the social and economic status of African Americans.” In the first two years they had 2,000 students visit. With so much traffic, by 1985 this former storefront could no longer easily accommodate so many. With the help of a $100,000 state grant and $100,000 in matched funds raised via donations, the museum moved into a former firehouse on East North Avenue. It is currently looking to relocate and expand once more.

The museum also explores the nooks and crannies of American history from which blacks tend to be left out. A good example is the Wild West, where African-Americans were buffalo soldiers, explorers, fur traders, trappers, cowboys, wranglers and homesteaders. Examples abound. The discovery of Arizona is attributed to fellow named Estevanico. Chicago was founded by Jean Baptiste Pointe Du Sable. Jim Beckworth was a mountain man who discovered one of the passes that allowed wagons to go farther west. Cherokee Bill was an infamous and much feared outlaw. According to one of the museum’s information signs, “so many blacks trekked westward between 1840 and 1890 that today there are more all-black towns in the West than any other section of the country.” One of which (though fictional) appears in the Netflix Western series Godless.

Torture and Branding

The museum highlights a number of black lives, most of whom Americans know little to nothing, about, at least not if they just read American history textbooks. Escaped slave Crispus Attucks was the first American to die in combat against the British during the American Revolution. Benjamin Banneker, a mathematical genius born in Maryland before the Revolution, was tasked by George Washington to layout the streets of the District of Columbia. Granville T. Woods, born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1856, became an engineer who took out fifty patents in his lifetime. He invented the “Synchronous Multiple Railway Telegraph,” which greatly increased the speed of communication for telegraphs and telephones. How that was done is well beyond me, but, according to the information sign, it “also allowed train engineers to be warned of trains in front or behind.”

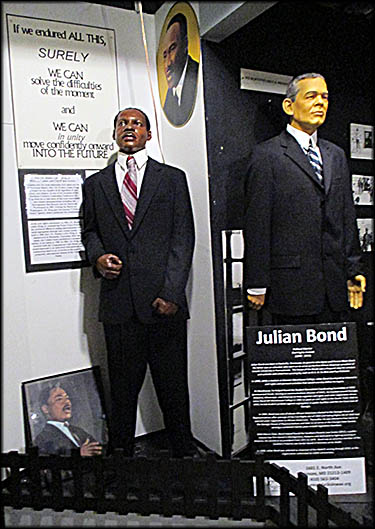

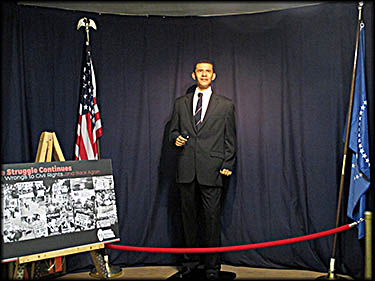

The museum’s main entrance hallway explores black history. Another hall is a peon to famous blacks in history such as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. Still another has wax figures of important contemporary or recently deceased African-Americans. This includes President Barak Obama, who has his own alcove and who African-American visitors stopped to revere with much pride. Another hall contains famous figures of the past who were black despite the fact history seems to have forgotten that fact. Probably the best known of these is Makeda, the Queen of Sheeba. Her union with King Solomon produced a royal line in Ethiopia that lasted until 1975.

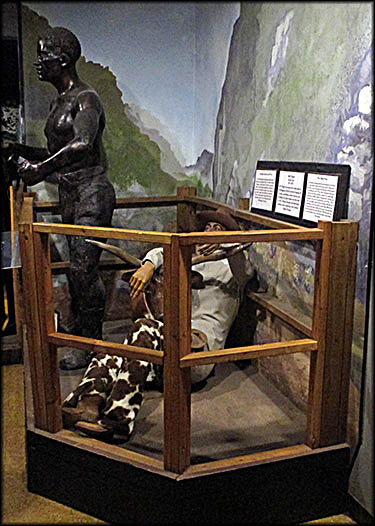

Despite ugly racist arguments to the contrary, blacks did not enjoy being slaves on any level. Henry Brown, for example, so hated this status he mailed himself in a crate made by a black carpenter from Richmond to Philadelphia. He then stood on said crate to preach against the evils of slavery. The most impressive part of this museum is its willingness to graphically demonstrate and explore the horrors of chattel slavery. One display shows a slave tortured by an iron mask, a device secured over the head with just enough holes to breath but not to take in food or water. It was placed on a slave who refused to be broken, forcing this victim to either starve to death or submit.

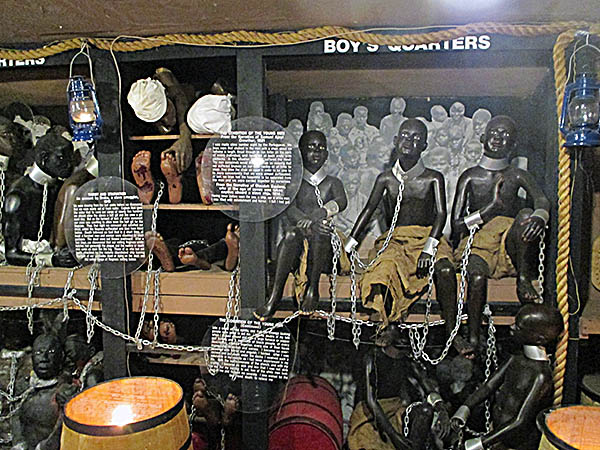

The willingness to cover the Middle Passage—the sea voyage from Africa to the Americas—without holding back its awfulness is one of the museum’s most powerful decisions. You descend down into the hold of a full scale model slave ship complete with a mirror on one side of the hull so, if you happen to be a person of color, you can see yourself as a slave. Here no punches are pulled. On board a transport vessel, the unskilled among the crew had the unwelcome task of feeding, exercising, and disciplining the slaves. They also died alongside them at the same appalling high rates. Some crewmen, when drunk, raped the women. One information sign reports an incident where a seaman raped a ten-year-old girl for three nights. It so damaged her psyche that her value dropped from 1.800 livres to 800 when she was sold at an auction.

Despite ugly racist arguments to the contrary, blacks did not enjoy being slaves on any level. Henry Brown, for example, so hated this status he mailed himself in a crate made by a black carpenter from Richmond to Philadelphia. He then stood on said crate to preach against the evils of slavery. The most impressive part of this museum is its willingness to graphically demonstrate and explore the horrors of chattel slavery. One display shows a slave tortured by an iron mask, a device secured over the head with just enough holes to breath but not to take in food or water. It was placed on a slave who refused to be broken, forcing this victim to either starve to death or submit.

The willingness to cover the Middle Passage—the sea voyage from Africa to the Americas—without holding back its awfulness is one of the museum’s most powerful decisions. You descend down into the hold of a full scale model slave ship complete with a mirror on one side of the hull so, if you happen to be a person of color, you can see yourself as a slave. Here no punches are pulled. On board a transport vessel, the unskilled among the crew had the unwelcome task of feeding, exercising, and disciplining the slaves. They also died alongside them at the same appalling high rates. Some crewmen, when drunk, raped the women. One information sign reports an incident where a seaman raped a ten-year-old girl for three nights. It so damaged her psyche that her value dropped from 1.800 livres to 800 when she was sold at an auction.

Given the chance, slaves being sailed to the Americas would kill their captives.

Those Africans unlucky enough to survive the voyage were taken ashore, cleaned up, given necessary medical attention, then, says an information sign, “crammed with food, and filled with liquids in an effort to fatten them up.” This was called “fattening.” In South America, the next step was “seasoning” or “breaking.” Effort was put into forcing them to discard their culture, language, and even names, which was often accomplished by working them nearly to death. If this failed to do the trick, there was also the bullwhip used to flog those who refused to submit. Pregnant women were not exempt from this form of torture: a hole would be dug to accommodate her belly, then she would lie prone on the ground for her beating. Masters sometimes made pretty slave girls and women into their personal prostitutes. About thirty percent of slaves died in the first three years from this process, an even greater number than the usual fifteen to twenty percent who died during the voyage. The majority of broken slaves stayed that way.

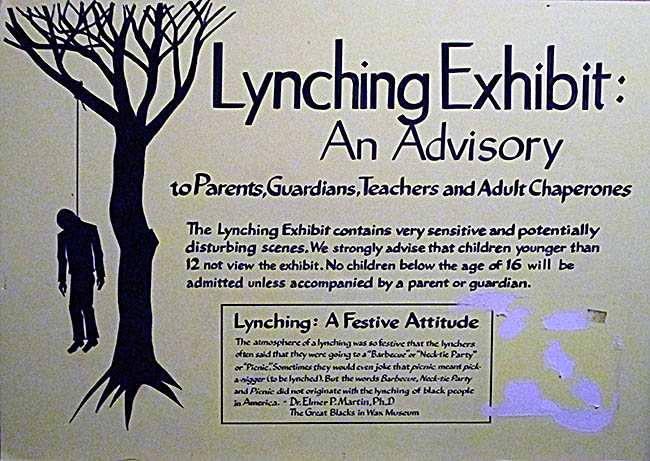

One section of the museum is forbidden to children under sixteen unless they are accompanied by an adult, guardian, or teacher. What could be even more heinous than the sights found in the slave ship? The gruesome history of lynching in the United States. Out of respect I did not take photos here. Lynching was used in both the North and South as a terror weapon to keep the African-American population submissive, and it went beyond a simple hanging. Often genitals were cut off, and it became so normalized in parts of Dixie, women and children sometimes gathered to watch.

Although President Harry Truman pushed for an federal anti-lynching law while in office, Congress never passed one then or since. Had it, the U.S. government could have prosecuted perpetrators if a state failed to do so. Probably the biggest reason lynching ended was the murder of Emmett Till in 1955. The massive publicity at the resulting murder trial made lynching so morally reprehensible that most Americans no longer wanted anything to do with it. The last known lynching of an African-American in the United States occurred in 1998 when three white supremacists chained James Byrd to the back of a truck and dragged him to death.🕜

Inside a Slave Ship

The iron mask would stay on until the slave submitted or died from lack of food and water.

Henry Brown mailed himself to freedom.

Jesse Jackson (left) and Julian Bond (right)

Queen of Sheba

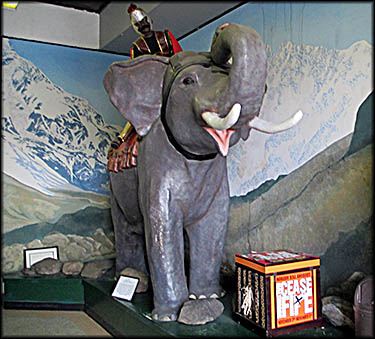

Hannibal Crossing the Alps to Invade Rome

President Barak Obama

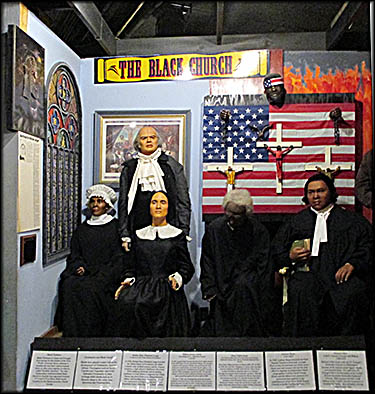

The Black Church

African Americans had a presence in the Wild West that is often overlooked.