National Museum of the U.S. Air Force

Fokker D.VIII

Caproni CA.36

B-10 Bomber

B-17 Bomber

U-2 Spy Plane

Apollo 15 Command Module Endeavor

B-2 Bomber

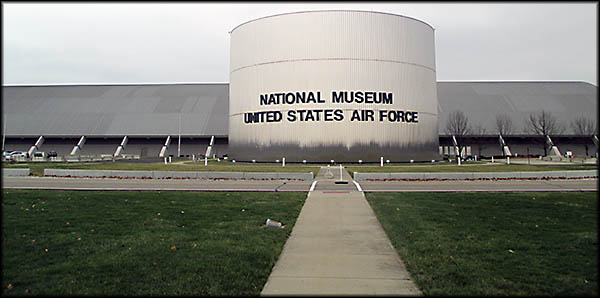

B-29 Bomber

Fall 1994. Dusk. Above me at a low attitude a triangular craft flew over my house that made no sound. I thought, “This is it. The aliens are coming to get me at last!” But no, it turned out to be a stealth fighter—the F-117A —whose existence had been revealed to the public just a few years earlier. My mom reported having had a similar sighting on another occasion during which she had also been awed by its silence. We decided that while visiting the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, we would make it a point to see this plane.

With my brother having come as well, we arrived at this epic-sized museum around 11:15 in the morning and foolishly decided to go through it before getting some lunch. We spent about four and half hours here, and even then we didn’t go everywhere. This is probably the largest museum in terms of square footage I’ve ever visited. To get through it all in one go, you need to possess a high amount of endurance. My brother and I both work out regularly and consider ourselves in excellent shape, but by the end of our visit we were exhausted. Worse, the floors are made of poured concrete, so our feet and backs and other body parts ached something awful. To alleviate this problem, the museum needs to invest in walkways constructed of a soft material like wooden blocks.

Those with a casual interest in aviation history should plan to spend between three to five hours here. Those who love planes and want to take a really good look at everything might want to consider dedicating a solid day or split their visit into a two day trip. Those who desire to read every single information sign in the place ought to plan on taking a good week because there are a mighty lot of them.

Those with a casual interest in aviation history should plan to spend between three to five hours here. Those who love planes and want to take a really good look at everything might want to consider dedicating a solid day or split their visit into a two day trip. Those who desire to read every single information sign in the place ought to plan on taking a good week because there are a mighty lot of them.

Although I’ve always had an interest in the history military and civilian aviation, I’m not the sort of enthusiast who knows a great deal about the more obscure craft. For someone like me, the museum if a treasure trove of new information. In World War I, the Allies used multi-engine heavy bombers designed by Italian engineer Gianni Caproni to attack their adversaries. In World War II, the Germans developed and used air-to-air missiles to shoot at B-17 bombers. During the Berlin Air Lift, Lieutenant Russ Steber brought his dog Vittles with him on many of the sorties he flew, prompting General Curtis LeMay of WWII fame to order a special parachute made for this loyal pooch.

The museum is set up as a series of four connected hangers arranged in chronological order starting with World War I and ending with the Cold War. Aficionados of aviation history won’t be disappointed. They will find everything from a WWI German Fokker D.VII to the P-26A fighter plane to a Huey helicopter (the Bell UH-1P Iroquois) as well as rare craft such as the Martin B-10, America’s first monoplane bomber with an all-metal fuselage.

The museum is set up as a series of four connected hangers arranged in chronological order starting with World War I and ending with the Cold War. Aficionados of aviation history won’t be disappointed. They will find everything from a WWI German Fokker D.VII to the P-26A fighter plane to a Huey helicopter (the Bell UH-1P Iroquois) as well as rare craft such as the Martin B-10, America’s first monoplane bomber with an all-metal fuselage.

Those interested in rockets will find a treasure trove of goodies in the Missile and Space room, including a Gemini capsule (not the one John Glenn used), the Apollo 15 command module Endeavour, and a large variety of missiles, including the Minute Man, America’s first solid fuel rocket ready to launch within a minute (thus its name). This area has an upstairs from which you can get a birds-eye view of the Cold War hanger from a small and not well-stocked snack bar. Hanging from the ceiling to the right is the U-2 spy plane, which my camera refused to focus on it. I had to take eight photos before I got a half-decent one. It’s as if it had stealth capabilities built into it.

It seems a pity that visitors can’t climb into the various craft on display, but you can hardly have people crawling all over and expect them to stay in pristine condition. There are a few exceptions. Visitors can walk through a detached section of a B-29 bomber’s fuselage as well as sit in the cockpits of a jet—minus the rest of the aircraft—and a jet trainer that no longer works. The museum also offers some interactive items, such as computer simulators for flying a plane, docking the Hubble Telescope with the space shuttle, and landing the shuttle itself.

I never did see the stealth fighter. It turns out the museum doesn’t have it. Instead it houses a different stealth plane, the B-2 bomber. Fortunately the museum’s many treasures offset my disappointment.🕜

It seems a pity that visitors can’t climb into the various craft on display, but you can hardly have people crawling all over and expect them to stay in pristine condition. There are a few exceptions. Visitors can walk through a detached section of a B-29 bomber’s fuselage as well as sit in the cockpits of a jet—minus the rest of the aircraft—and a jet trainer that no longer works. The museum also offers some interactive items, such as computer simulators for flying a plane, docking the Hubble Telescope with the space shuttle, and landing the shuttle itself.

I never did see the stealth fighter. It turns out the museum doesn’t have it. Instead it houses a different stealth plane, the B-2 bomber. Fortunately the museum’s many treasures offset my disappointment.🕜

The museum also has a surprise in store for visitors: between the World War I and World II hangers is a small room about the Holocaust called “Prejudice and Memory” that contains photos and memories from survivors who lived in the Dayton area. When approaching it from the correct direction, you will first see a concentration camp uniform belonging to Moritz Bomstein that he wore while in Buchenwald. Because “Prejudice and Memory” is in the heart of a museum of dedicated to aviation history, one of its information plaques mentions that during WWII the Germans often considered American bomber pilots shot down in German territory war criminals rather than prisoners of war, and as such threw them into concentration rather than POW camps.