National Museum of the Great Lakes

National Museum of the Great Lakes

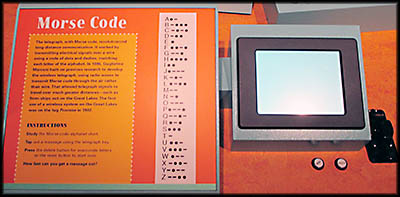

When you use the telegraph, what you sent shows up on the computer screen.

Inside the Museum

Unidentified Figurehead

Since finishing Shanghaiing Sailors and redirecting all my research and writing efforts to an entirely different subject, I don’t think I’ve gone to a nautical museum in quite a few years. I wanted to visit it for two reasons. First, I’d been to its old location in Vermilion, Ohio, and desired to see how it had changed after moving to Toledo. Second, I longed to tour the Col. James M. Schoonmaker, a lake freighter moored beside the museum that was not at the Vermillion location. Despite having lived all my life near Lake Erie, I’ve never had a chance to climb on board one.

The National Museum of the Great Lakes is a completely different place than the one in Vermilion and probably the only similarity between the two is that they share the artifacts on display. The museum has a number of interactive things here to engage children, although I’ll admit I couldn’t resist trying out a for few myself (especially the telegraph that, when you use it, shows the messages you output on a computer screen). In the main entry a movie plays repeatedly that gives you a good overview of the history of the Great Lakes, their diversity, and so forth. The screen sets in the middle of a circular room filled with information displays of each lake complete with 3-D maps that show a given lake’s depths. I rather like this sort of thing and spent quite some time combing over them. It’s amazing just how shallow, for example, Lake Erie is compared to the other four.

The National Museum of the Great Lakes is a completely different place than the one in Vermilion and probably the only similarity between the two is that they share the artifacts on display. The museum has a number of interactive things here to engage children, although I’ll admit I couldn’t resist trying out a for few myself (especially the telegraph that, when you use it, shows the messages you output on a computer screen). In the main entry a movie plays repeatedly that gives you a good overview of the history of the Great Lakes, their diversity, and so forth. The screen sets in the middle of a circular room filled with information displays of each lake complete with 3-D maps that show a given lake’s depths. I rather like this sort of thing and spent quite some time combing over them. It’s amazing just how shallow, for example, Lake Erie is compared to the other four.

I found the museum’s circular layout difficult to navigate. It is divided into a number of sections—Life Saving, Ship Wrecks, Ship Building, and so forth—but they blend into one another, and the confusing layout makes it easy to miss stuff. The museum also suffers from information overload. There are just too many signs to read for a person to reasonably get through without spending eight hours doing nothing else.

You certainly learn a lot here. During World War II, the Seeandbee, a side-wheeler steamer built in 1913 in Detroit, was converted into an aircraft carrier named the USS Wolverine for pilot training. From this and another converted lake vessel, the USS Sable, pilots such as George H. W. Bush learned how to take off and land on carriers. The Lyle gun was developed by Captain David A. Lyle in 1877 as a means of shooting a lifeline from the shore out to a distressed vessel. Its line was made out of waterproofed braided linen that had to be shot a few times to make it more flexible and to flake correctly (“flaking,” according to the museum’s sign, is a line “wound so it could be shot without tangling”). Another sign reported, “There are 326 lighthouses dotting the Great Lakes 10,900 mile coastline. That’s one lighthouse for every 33 miles—more than anywhere else in the world!”

I knew that a lot of ships were built on the lakes and that most of those shipyards have since closed, but I had no idea why. The main reason was the switch from wood to steel as a construction material. Steel ships last for so much longer than wooden ones they aren’t replaced that often, severely cutting into the number a yard needs to build in a year. That and the overall decline of manufacturing in the United States have caused the closure of many of them.

The Great Lakes once had a vibrant cruise industry, something I didn’t know. So what happened to it? Why are the lakes reduced to just a few car ferries and novelty cruises these day? A number of factors contributed to its extinction. One key event occurred in 1949. In that year, 128 passengers died on the Noronic when she burned at a dock in Toronto. This prompted the passage of stricter safety regulations that required companies running passenger vessels to retrofit their existing fleets or to build new ones. Because air and car travel had started to become the preferred means of transportation in Canada and the United States, this was not an economically viable option, so over a short time the lot of them went out of business.

My traveling companions and I went on board the lake freighter Col. James M. Schoonmaker an hour before it was due to shut down for the day. As it turned out, we finished just as she was closing, so make sure you set aside plenty of time to see her. The Schoonmaker was launched in Ecorse, Michigan, on July 1, 1911. When sold in 1969, her new owner rechristened her the Willis B. Boyer. She remained this until the City of Toledo bought her in 1987 and changed her name back to its original. In 2006, the city began a restoration effort that finished in 2011. Maintenance and upkeep are still being done.

My traveling companions and I went on board the lake freighter Col. James M. Schoonmaker an hour before it was due to shut down for the day. As it turned out, we finished just as she was closing, so make sure you set aside plenty of time to see her. The Schoonmaker was launched in Ecorse, Michigan, on July 1, 1911. When sold in 1969, her new owner rechristened her the Willis B. Boyer. She remained this until the City of Toledo bought her in 1987 and changed her name back to its original. In 2006, the city began a restoration effort that finished in 2011. Maintenance and upkeep are still being done.

Aboard you go on a self tour by following yellow arrows on the deck. Starting near the bow, you head aft towards the crew’s quarters, galley, mess quarters, officer’s dining room, and engine room. Along the way there is a stop below to see one of the cargo holds. The first crew quarter we saw had been occupied by the chief engineer. Though small and sparse, I figured this was luxurious for this type of working vessel. The crew quarters were even sparser and contained some pretty uncomfortable beds. The crew’s mess was utilitarian, and the galley stainless steel. My jaw about dropped when we entered the officer’s dining room. Instead of plain metal walls painted with colors liable to drive a person insane, this room had wood paneling.

This little surprise was nothing compared to what we saw next. We headed forward to the forecastle and there into the Passenger’s Hall. To the left as you go through its hatch there is a wooden staircase of the type you would find in a Gilded Age mansion. Go down to the end of the hall you enter the oak-paneled grill room (so called because there is an electric grill in the center of its far wall). Here a sign informs visitors that the vessel’s original owner, William P. Snyder, used these quarters as a passenger lounge. The parts of the ship he inhabited were designed to be the sort of luxurious space he and his guests, who included Andrew Carnegie, would expect. The captain’s quarters and office were just as spectacular. I never imagined something like existed on a freighter, especially one as old as this.

Aside from being crafted as a space in which millionaires could feel at ease, this opulence it served a second, more insidious purpose. It reinforced a naval social hierarchy based on the English aristocracy. The crew were the peasants. The steward, chief engineer, and other skilled men were the middle class. The officers were the aristocracy (or gentlemen). The captain was the prime minister, and the owner the king.🕜

This little surprise was nothing compared to what we saw next. We headed forward to the forecastle and there into the Passenger’s Hall. To the left as you go through its hatch there is a wooden staircase of the type you would find in a Gilded Age mansion. Go down to the end of the hall you enter the oak-paneled grill room (so called because there is an electric grill in the center of its far wall). Here a sign informs visitors that the vessel’s original owner, William P. Snyder, used these quarters as a passenger lounge. The parts of the ship he inhabited were designed to be the sort of luxurious space he and his guests, who included Andrew Carnegie, would expect. The captain’s quarters and office were just as spectacular. I never imagined something like existed on a freighter, especially one as old as this.

Aside from being crafted as a space in which millionaires could feel at ease, this opulence it served a second, more insidious purpose. It reinforced a naval social hierarchy based on the English aristocracy. The crew were the peasants. The steward, chief engineer, and other skilled men were the middle class. The officers were the aristocracy (or gentlemen). The captain was the prime minister, and the owner the king.🕜

Lyle Gun

Col. James M. Schoonmaker Entrance

Col. James M. Schoonmaker Grill Room

Col. James M. Schoonmaker

Owner’s Stateroom

Owner’s Stateroom

Col. James M. Schoonmaker Bridge

Col. James M. Schoonmaker

Passenger Hall

Passenger Hall

Col. James M. Schoonmaker

Captain’s Office

Captain’s Office

Promotional Material for Lake Cruises