National Packard Museum

Museum Entrance

Inside the Museum

The National Packard Museum wasn’t originally on my agenda. When I arrived in Warren, I’d planned to visit the John Stark Edwards House, but despite the sign out front assuring me it was open, it wasn’t. This sometimes happens with museums staffed with volunteers. Across the street I saw the Warren-Trumbull County Library, so I went there to see if anyone there knew why the museum wasn’t open. Although they thought it strange no one was there, they had no idea why. Informed that library had its own museum, the Sutcliff, I headed upstairs to see that.

This one-room museum is a beautiful replica of a room in an upper-class Victorian home. It outlines the history of the Sutcliff family, abolitionists who worked for the Underground Railroad. The trouble was by this point I already had three chapters for my new book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio touching on this topic, so I decided not to include it. So where else could I go? Again the excellent library staff helped me. Why didn’t I check out the National Packard Museum just a few blocks away? This was definitely open. Because I live two hours away from Warren and had no desire to return at a later point, I decided to check it out.

The museum was founded by Theodore M. Martin, Jr.—Terry to his friends—who was born in Chester, West Virginia, on November 10, 1936. He moved his wife and children to Warren in 1963 when he took a job there at a cabinet making business. An antique car enthusiast, the first vintage auto he bought was a 1926 Buick sedan. In 1968 while visiting a car show in Hershey, Pennsylvania, he noticed that a 1900 Packard’s brass nameplate said, “New York and Ohio Company.” So far as he knew, Packard had been a Detroit car maker, so, intrigued, he looked into this. And lo and behold, the company had started in Warren. At the 1972 Hershey car show he posted a note that he wanted to buy a Packard. Someone sold him a one-cylinder Packard built in 1900, the first of many he would purchase.

The museum was founded by Theodore M. Martin, Jr.—Terry to his friends—who was born in Chester, West Virginia, on November 10, 1936. He moved his wife and children to Warren in 1963 when he took a job there at a cabinet making business. An antique car enthusiast, the first vintage auto he bought was a 1926 Buick sedan. In 1968 while visiting a car show in Hershey, Pennsylvania, he noticed that a 1900 Packard’s brass nameplate said, “New York and Ohio Company.” So far as he knew, Packard had been a Detroit car maker, so, intrigued, he looked into this. And lo and behold, the company had started in Warren. At the 1972 Hershey car show he posted a note that he wanted to buy a Packard. Someone sold him a one-cylinder Packard built in 1900, the first of many he would purchase.

The Packard Statue

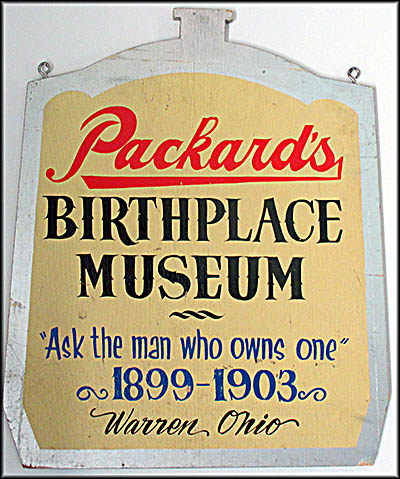

In 1974 he and his wife, Lorna, organized and ran the seventy-fifth anniversary celebration of Packard in Warren. It brought together about 200 people and almost 100 Packards. Attendees visited the place where the first Packard was built, toured Packard family homes and historical sites associated with the company, and viewed a slideshow. Lehigh University allowed its Packard Model A, the very first Packard ever produced, to travel to Warren for the occasion. In the same year Martin opened the Packard’s Birthplace Museum in part of his house’s kitchen and bathroom. Warren Packard III was on hand to cut the dedication ribbon. The museum had just one auto part, a Blackmore engine, on display.

In 1982 Martin bought a Packard Model F that he planned to restore and drive from San Francisco to New York City to honor a trip performed in 1903 in by a Packard Overland Car driven by E.T. Fetch. On June 20 of that year, Fetch along with passenger M.C. Krarup departed from a San Francisco garage owned by Packard agent Harold Larsalere. They took a ferry to Oakland, then drove to Porta Costa for a total of thirty-eight miles that first day. All went well save for an overheated bearing that might have been caused by sabotage. The two men nicknamed their car the Pacific.

In 1982 Martin bought a Packard Model F that he planned to restore and drive from San Francisco to New York City to honor a trip performed in 1903 in by a Packard Overland Car driven by E.T. Fetch. On June 20 of that year, Fetch along with passenger M.C. Krarup departed from a San Francisco garage owned by Packard agent Harold Larsalere. They took a ferry to Oakland, then drove to Porta Costa for a total of thirty-eight miles that first day. All went well save for an overheated bearing that might have been caused by sabotage. The two men nicknamed their car the Pacific.

They crossed the Sierra Mountains on June 24 via Placerville, California, Getting to the 7,300 feet summit of the Sierras was at that point considered by some in Placerville impossible for an automobile to manage, so imagine its citizens’ surprise when a Packard drove into town. As Fetch and Krarup headed back down out of the mountains, their bronze and iron brake heated up so much that water sizzled when dropped on it.

After reaching Reno, Nevada, the travelers headed to Wadsworth, Nevada, by crossing low sandy hills with no road. For a time they followed the Humboldt River. Weather and terrain proved daunting but not impassable. They reached Chicago on August 10 and New York City on August 21, sixty-one days after their departure. This was not the very first car to make a successful journey across America from coast to coast. That had been done earlier in the year by Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson and Sewall K. Crocker. Departing from San Francisco in a Winton on May 23, 1903, they drove it all the way to New York. After restoring his own Model F, which he called the Old Pacific II, Martin and a party of family members departed in June and retraced the Old Pacific’s trip in sixty-three days.

In 1989 Martin helped organize the Packard Museum Association to establish a larger museum dedicated to the history of the family and Packard Motor. Martin loaned much of his collection to this new venture, which opened its doors on August 22, 1989, in the Kinsman House. It moved to its current location on July 4, 1999, opening as the National Packard Museum. Martin died on February 10, 2019, at the age of eighty-two.

In 1989 Martin helped organize the Packard Museum Association to establish a larger museum dedicated to the history of the family and Packard Motor. Martin loaned much of his collection to this new venture, which opened its doors on August 22, 1989, in the Kinsman House. It moved to its current location on July 4, 1999, opening as the National Packard Museum. Martin died on February 10, 2019, at the age of eighty-two.

The museum’s collection of Packard cars is extensive. The thing that struck me most about them is just how big they were. Excluding stretched limos, which a number of Packards were made into, few modern American cars produced today come close to their size in length and width. One Packard on display measured 18 feet in length and 6½ feet in width. The closest 2020 car I could find to this is the Lincoln Continental. It measures 16¾ feet long and 6½ feet wide.

The 1956 Packard Patrician made its debut at dealerships on November 3, 1955. According to the accompanying information sign, it “offered a lavish interior with beautiful new color combinations, lush fabrics, and plush carpeting. Packard’s 1956 models were loaded with innovative features including a powerful V-8 engine, dual-range automatic transmission, and Torsion Level Ride suspension. Despite receiving glowing reviews from the automotive press, car sales plunged in 1956.” It was too much. Packard closed its Detroit factory that summer and merged with Studebaker out of South Bend, Indiana. Studebaker-Packard produced its last Packard in 1958, then in 1962 dropped “Packard” from its name. Studebaker went under in the United States the next year. Its Canadian operations shuttered in 1966.

In addition to showing off an impressive collection of cars, the museum has items once owned by the Packard family including dresses worn by Elizabeth “Bess” Packard and a Smith & Wesson .39 double action Perfected Revolver owned by James Ward Packard. A showpiece, Tiffany added diamonds, an ivory handle, and platinum and gold overlays to it, then shipped it to Packard in May 1910. According to the museum staff, it’s doubtful it that anyone ever fired it.🕜

The 1956 Packard Patrician made its debut at dealerships on November 3, 1955. According to the accompanying information sign, it “offered a lavish interior with beautiful new color combinations, lush fabrics, and plush carpeting. Packard’s 1956 models were loaded with innovative features including a powerful V-8 engine, dual-range automatic transmission, and Torsion Level Ride suspension. Despite receiving glowing reviews from the automotive press, car sales plunged in 1956.” It was too much. Packard closed its Detroit factory that summer and merged with Studebaker out of South Bend, Indiana. Studebaker-Packard produced its last Packard in 1958, then in 1962 dropped “Packard” from its name. Studebaker went under in the United States the next year. Its Canadian operations shuttered in 1966.

In addition to showing off an impressive collection of cars, the museum has items once owned by the Packard family including dresses worn by Elizabeth “Bess” Packard and a Smith & Wesson .39 double action Perfected Revolver owned by James Ward Packard. A showpiece, Tiffany added diamonds, an ivory handle, and platinum and gold overlays to it, then shipped it to Packard in May 1910. According to the museum staff, it’s doubtful it that anyone ever fired it.🕜

The original museum sign.

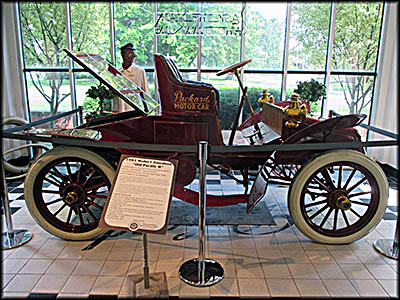

Old Pacific II

Packard Model F

1956 Packard Caribbean Hardtop

It is unlikely this Smith & Wesson pistol ordered from Tiffany's by James Packard was ever fired.