National Road & Zane Grey Museum

The famous Y-bridge in Zanesville.

Dawes Arboretum

PART 1: The Road to the Museum

It took me three tries to visit the National Road & Zane Grey Museum in Norwich, Ohio. My odyssey began in the fall of 2014 when my mom asked me to drive her down to southern Ohio in the latter half of October to see the Autumn leaves. I decided to go to the Zanesville area for this because I hadn’t been there in a long time. Before departing, I looked up local attractions and thought I might like to stop at the National Road Museum while there.

Using Yelp!, I found along our route the Amish restaurant Miller’s Dutch Kitch’n in Baltic, Ohio, which we stopped at for lunch. (The restaurant has since gone out of business.) Although neither its exterior nor interior reflected the Amish-style of architecture one would associate with such an establishment, its food was wonderful. Though I call it an Amish restaurant because that’s what Yelp! listed it as, I suspect it is run by Mennonites both because the “Amish” working there wear colorful clothing and it has an official website, something the Amish aren’t known for.

Our primary goal that day aside from looking at colorful leaves (which we in any case failed to find) was to visit a place called Dawes Arboretum where one can find flowers, interesting landscaping, and a pleasant place to walk. We spent so long there that we lacked the time to visit to the National Road Museum, so I decided would return another day to see it.

This did not happen until the last week of May 2016. For this venture, my aunt asked to come along because she is a huge fan of Zane Grey and has waited longer than forty years to visit the museum. Remembering how tasty Miller’s Dutch Kitch’n was, I decided we’d stop there for lunch. This, it turns out, was my first mistake of the day. My new and improved GPS decided the fastest way there was to take me through the back roads of Holmes County where, despite the fact I had it set to avoid them, it took me along unimproved roads, most of them dirt rather than gravel, forcing me to go a maximum of 25 mph. For what seemed like hours we wandered about in an area with no cell phone service and few electric poles. The dust was so thick my car changed from gray to brown. I can’t remember seeing a single human in this wilderness.

Using Yelp!, I found along our route the Amish restaurant Miller’s Dutch Kitch’n in Baltic, Ohio, which we stopped at for lunch. (The restaurant has since gone out of business.) Although neither its exterior nor interior reflected the Amish-style of architecture one would associate with such an establishment, its food was wonderful. Though I call it an Amish restaurant because that’s what Yelp! listed it as, I suspect it is run by Mennonites both because the “Amish” working there wear colorful clothing and it has an official website, something the Amish aren’t known for.

Our primary goal that day aside from looking at colorful leaves (which we in any case failed to find) was to visit a place called Dawes Arboretum where one can find flowers, interesting landscaping, and a pleasant place to walk. We spent so long there that we lacked the time to visit to the National Road Museum, so I decided would return another day to see it.

This did not happen until the last week of May 2016. For this venture, my aunt asked to come along because she is a huge fan of Zane Grey and has waited longer than forty years to visit the museum. Remembering how tasty Miller’s Dutch Kitch’n was, I decided we’d stop there for lunch. This, it turns out, was my first mistake of the day. My new and improved GPS decided the fastest way there was to take me through the back roads of Holmes County where, despite the fact I had it set to avoid them, it took me along unimproved roads, most of them dirt rather than gravel, forcing me to go a maximum of 25 mph. For what seemed like hours we wandered about in an area with no cell phone service and few electric poles. The dust was so thick my car changed from gray to brown. I can’t remember seeing a single human in this wilderness.

2 The only saving grace here is we passed through a little horse town in which I saw a harness and tackle shop. Because no retailer within 100 miles of my house carries a belt made with 100 percent leather, I decided to stop in to see if this shop sold them. When I asked an Amish man working there if they had any, he showed me a rack filled to the brim with them. He also offered to make me one if I didn’t like any of them. Overwhelmed with good choices, the one I chose was just $21! I can’t imagine Macys, Target, or JCPenny charging that for one.

Another hour’s travel after our stop at Miller’s Dutch Kitch’n, brought us to the National Road Museum. Much to our horror, we found it closed. This was my second mistake of the day. I had gotten its hours confused with another museum I had planned to visit in the same week. We nonetheless got out to look at the few displays on the ground. While doing this another car drove in. Those within had traveled two hours to get here and were as disappointed as us that it was closed. Their misfortune was our good fortune. It turned out one of them used to live in nearby Zanesville. He told us that his cousin ran the restaurant Muddy Misers Cool River Café there, and it was filled with authentic Zane Grey memorabilia. He also informed us of a park from which we would see Zanesville’s unique Y-bridge from far above.

Muddy Misers Cool River Café’s staff graciously let look at their Zane Grey displays even though we didn’t plan to eat or drink. Items included letters, photos, a gun or two, and all sorts of other things owned by Zane Grey. My aunt loved it; the trip was saved. After that we spent our remaining time in the area at Dawes Arboretum. I later learned Muddy Miser was a local eccentric who served as a father figure to Zane Grey and taught him much about the outdoors.

Another hour’s travel after our stop at Miller’s Dutch Kitch’n, brought us to the National Road Museum. Much to our horror, we found it closed. This was my second mistake of the day. I had gotten its hours confused with another museum I had planned to visit in the same week. We nonetheless got out to look at the few displays on the ground. While doing this another car drove in. Those within had traveled two hours to get here and were as disappointed as us that it was closed. Their misfortune was our good fortune. It turned out one of them used to live in nearby Zanesville. He told us that his cousin ran the restaurant Muddy Misers Cool River Café there, and it was filled with authentic Zane Grey memorabilia. He also informed us of a park from which we would see Zanesville’s unique Y-bridge from far above.

Muddy Misers Cool River Café’s staff graciously let look at their Zane Grey displays even though we didn’t plan to eat or drink. Items included letters, photos, a gun or two, and all sorts of other things owned by Zane Grey. My aunt loved it; the trip was saved. After that we spent our remaining time in the area at Dawes Arboretum. I later learned Muddy Miser was a local eccentric who served as a father figure to Zane Grey and taught him much about the outdoors.

PART 2: The Museum

National Road & Zane Grey Museum

My third attempt to get to the museum hit no snags. Circumventing Miller’s Dutch Kitch’n altogether, my mom, aunt and I headed directly for the museum. This time I’d first plotted out a decent route in case my GPS had other ideas. It took us about three hours to get there. Thankfully the parking lot had a good number of cars in it. I had come here not because of Zane Grey, an author whose books I don’t especially like, but rather because of my interest in the National Road. I thought it was a bit odd that the museum covered such seeming different topics, so I asked someone there about it. It turned out they are connected after all. Zane Grey was directly descended on his mother’s side from the man contracted to build the National Road, Colonel Ebenezer Zane, who is also considered the founder of Zanesville.

The person who sold us the tickets tried to entice us to visit the nearby John and Annie Glenn Museum (Glenn’s boyhood home), which seemed a bit odd to me. It turned out that in 2009 those in charge of it had taken managerial control of the National Road Museum, which is owned by the Ohio History Connection (formally the Ohio Historical Society). This is a good thing because OHC sites have fallen on hard times due to funding cuts and are, for the most part, not especially good these days.

The new management has, among other things, introduced guided tours, which came as quite a surprise to me since most OHC sites lack these. I am ashamed to admit that I forgot to record the name of our guide, who was informative, personable, and willing to talk about more than just the museum. We couldn’t have had a better person to give us our tour.

The history of the National Road begins shortly after the American Revolution when a large number of Americans moved into Ohio and the surrounding areas. Thick forests made it impossible for farmers to get their crops to markets in the East. Instead they distilled them into whiskey, which was much easier to transport. The National Road, envisioned by George Washington and his contemporaries, would remedy this issue, promote commerce, and help to connect the West to the East.

The person who sold us the tickets tried to entice us to visit the nearby John and Annie Glenn Museum (Glenn’s boyhood home), which seemed a bit odd to me. It turned out that in 2009 those in charge of it had taken managerial control of the National Road Museum, which is owned by the Ohio History Connection (formally the Ohio Historical Society). This is a good thing because OHC sites have fallen on hard times due to funding cuts and are, for the most part, not especially good these days.

The new management has, among other things, introduced guided tours, which came as quite a surprise to me since most OHC sites lack these. I am ashamed to admit that I forgot to record the name of our guide, who was informative, personable, and willing to talk about more than just the museum. We couldn’t have had a better person to give us our tour.

The history of the National Road begins shortly after the American Revolution when a large number of Americans moved into Ohio and the surrounding areas. Thick forests made it impossible for farmers to get their crops to markets in the East. Instead they distilled them into whiskey, which was much easier to transport. The National Road, envisioned by George Washington and his contemporaries, would remedy this issue, promote commerce, and help to connect the West to the East.

Congress began selling lands to raise the funds for the road in April 1802. Engineering began in 1806 when Colonel Ebenezer Zane won the contract to build it. It soon became apparent a leveled dirt road would not do—a bit of rain and wagons sank into it—so engineers tried covering it with logs (a corduroy road), but these just broke up. Finally a road construction technique developed by Scotsman John McAdam was used. Called macadam, it is a process in which layers of gravel are piled upon one another, the largest stones being at the bottom and the smallest at the top. The finished road went from Cumberland, Maryland to St. Louis, Missouri. Spanning nearly 700 miles, by 1840 it had become the most used road in America. Parts of it have become present day U.S. Route 40.

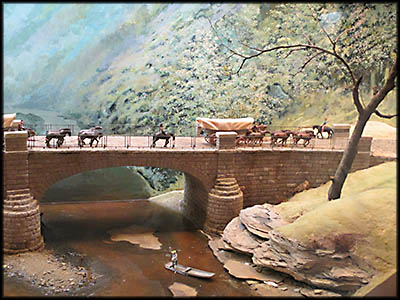

Along the museum’s outside wall snakes one of the most spectacular dioramas I’ve seen. Spanning 136 feet and showing the National Road as it once was, those who created it were master artists. The detail of its structures, painted backgrounds, and especially its figures is phenomenal. The figures in particular are a wonder to look at. Each has its own personality and is doing more than just standing there. One fellow, for example, is being pushing another into the Muskingum River.

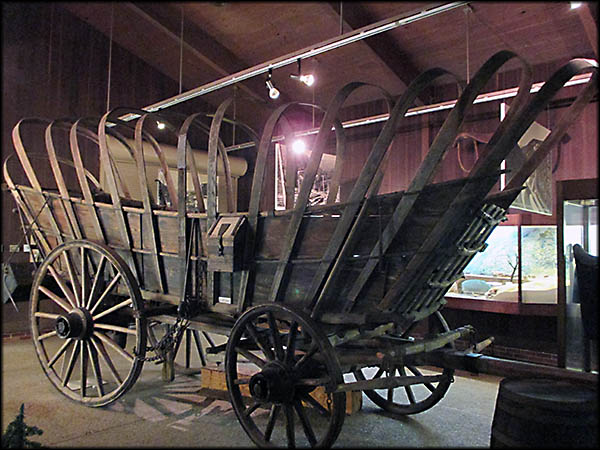

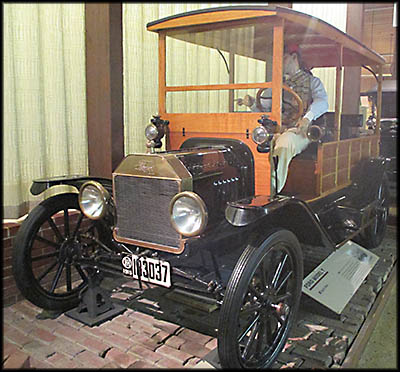

Although the museum is relatively small, the rooms dedicated to the National Road are packed full of vehicles, artifacts, art, and historical recreations of rooms complete with detailed manikins. One will find, for example, a 1908 Stanley Steamer, a carriage converted to a sleigh built in he early part of the nineteenth century, and, best of all, a real Conestoga wagon, a form of early nineteenth transport that was, as our guide put it, the 18-wheeler of its day. Conestoga wagons were large, extremely heavy, and needed eight horses and oxen (or a combination therefore) just to move. Their brakes were lined with shoe leather, explain why today we use the term “brake shoe” for our cars. Despite what some of our American history schoolbooks say, Conestoga wagons were not widely used west of the Mississippi because they were just too heavy to go across the grasslands, mountains, and deserts of the American West.

Along the museum’s outside wall snakes one of the most spectacular dioramas I’ve seen. Spanning 136 feet and showing the National Road as it once was, those who created it were master artists. The detail of its structures, painted backgrounds, and especially its figures is phenomenal. The figures in particular are a wonder to look at. Each has its own personality and is doing more than just standing there. One fellow, for example, is being pushing another into the Muskingum River.

Although the museum is relatively small, the rooms dedicated to the National Road are packed full of vehicles, artifacts, art, and historical recreations of rooms complete with detailed manikins. One will find, for example, a 1908 Stanley Steamer, a carriage converted to a sleigh built in he early part of the nineteenth century, and, best of all, a real Conestoga wagon, a form of early nineteenth transport that was, as our guide put it, the 18-wheeler of its day. Conestoga wagons were large, extremely heavy, and needed eight horses and oxen (or a combination therefore) just to move. Their brakes were lined with shoe leather, explain why today we use the term “brake shoe” for our cars. Despite what some of our American history schoolbooks say, Conestoga wagons were not widely used west of the Mississippi because they were just too heavy to go across the grasslands, mountains, and deserts of the American West.

His books translated well into movies. As of this writing, over 100 based on them have been made. In 1918, he moved to California, and in 1919 founded his own motion picture company, Zane Grey Productions. Not being a very good businessman, he sold his interests to Jesse Lasky, whose studio became Paramount Pictures. Many actors starred in the movies based on Grey’s books, including Gary Cooper and Roy Rogers. The most recent adaption, Riders of the Purple Sage, appeared in 1996. Starring Ed Harris and Amy Madigan, it was the fifth movie version of this work. There was also a television series called Dick Powell’s Zane Grey Theater that ran on CBS from 1956 to 1961.

The National Museum had one more surprise for us. It has a room dedicated to pottery made in the area. It turns out that the abundant red clay from which the road was dug was also excellent for making ceramics. As a result, a number of pottery factories burst onto the scene, though in time they all went out of business. Potters sometimes took clay right from the road, which resulted in “potholes.” The museum’s pottery collection is quite impressive to say the least, a big compliment from me considering ceramics are my least favorite form of art.🕜

The National Museum had one more surprise for us. It has a room dedicated to pottery made in the area. It turns out that the abundant red clay from which the road was dug was also excellent for making ceramics. As a result, a number of pottery factories burst onto the scene, though in time they all went out of business. Potters sometimes took clay right from the road, which resulted in “potholes.” The museum’s pottery collection is quite impressive to say the least, a big compliment from me considering ceramics are my least favorite form of art.🕜

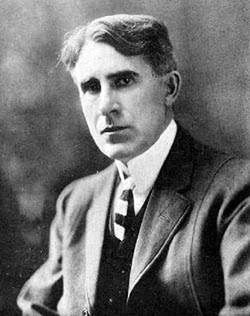

After exhausting the supply of National Road exhibits, we moved on to the Zane Grey section, which is considerably smaller in area but jam packed with artifacts from his life, including the room in which he wrote many of his books brought here from his home in California. Grey’s life is fascinating. His first name was Pearl of all things. Zane was his middle name. The son of an abusive father who had practiced many trades including dentistry, Zane himself always wanted to be a writer though he nearly became a professional baseball player instead. At his father’s insistence, he learned dentistry and set up a practice in New York City. This he hated. Here he started spelling as “Grey” rather than “Gray.” At the urging of his wife, Line Elise Roth (Dolly), he decided to become a fulltime writer, and throughout his career, his wife always typed out his manuscripts and corrected grammatical errors. Failing to find a publisher for his first novel, Betty Zane, which was about his great-great grandmother’s heroism during the American Revolution, he paid to have it printed using a loan from his wife, who had a small inheritance.

At first neither it nor his articles and non-Western books sold well. Nor, for the matter, did his first historical Western, The Heritage of the Desert. Distraught, he nearly wrote nothing else, but at his wife’s insistence he penned Riders of the Purple Sage. Which Ripley Hitchcock, the editor from Harper & Bros. who had bought Heritage, rejected. Fortunately Grey convinced Harper’s vice president to read it. This man and his wife liked it so much Harper published the book anyway, although Hitchcock made editorial changes. Released in 1909, it made Grey so popular that he eventually became America’s best selling novelist. His books sold better than those of contemporaries William Faulkner, Ernest Hemmingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Despite his success, terrible depression often gripped him. He also suffered from chronic money problems. Although he earned millions, his spendthrift nature often left him broke. When that happened, his wife saw to it that he wrote another book so he could refill the coffers. And though they had a happy marriage, he was a notorious womanizer. A keen fisherman and hunter, he often took his lovers with him for his outdoors adventures, sometimes complaining about them in letters to his wife!

At first neither it nor his articles and non-Western books sold well. Nor, for the matter, did his first historical Western, The Heritage of the Desert. Distraught, he nearly wrote nothing else, but at his wife’s insistence he penned Riders of the Purple Sage. Which Ripley Hitchcock, the editor from Harper & Bros. who had bought Heritage, rejected. Fortunately Grey convinced Harper’s vice president to read it. This man and his wife liked it so much Harper published the book anyway, although Hitchcock made editorial changes. Released in 1909, it made Grey so popular that he eventually became America’s best selling novelist. His books sold better than those of contemporaries William Faulkner, Ernest Hemmingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Despite his success, terrible depression often gripped him. He also suffered from chronic money problems. Although he earned millions, his spendthrift nature often left him broke. When that happened, his wife saw to it that he wrote another book so he could refill the coffers. And though they had a happy marriage, he was a notorious womanizer. A keen fisherman and hunter, he often took his lovers with him for his outdoors adventures, sometimes complaining about them in letters to his wife!

Zane Grey

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Posters for just a few movies

based on Zane Grey books.

based on Zane Grey books.

The room in which Zane Grey

wrote many of his books.

wrote many of his books.

Zane Grey Display

Pottery Room

National Road Diorama

Ford Model T Depot Hack

Stanley Steamer

This is Zane's first novel about the Ohio frontier based on his great-great aunt's life.

Conestoga Wagon