Oak Hill Cottage

Oak Hill Cottage (Front)

Oak Hill Cottage (Side)

Entrance Hall

Parlor

Sitting Room

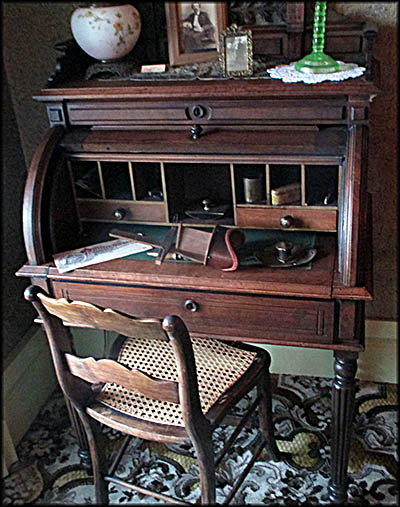

Doctor Johannes Aten Jones' Desk

Desk Lamp

Dolls in the Nursey that belonged the daughters.

Dining Room

Girl's Dress and Slip

Servants' Quarters

This wedding dress was worn by Ida Jones as well as her granddaughter and great-granddaughter.

Statue of Daniel Webster

During my childhood, my family often visited relatives in Indiana who had cottages on small lakes. These dwellings were not especially large, stood one story, and were meant to be lived in mainly during the warm months of the year. To my mind, cottages are small houses. Dictionary definitions back this. The Oxford English Dictionary says a cottage is “a small house, typically simple or basic in construction, such as is, or was formerly, intended to be occupied by a farm labourer, villager, miner, fisherman, etc.” And Dictionary.com says that a cottage is “a small house, usually of only one story.”

Oak Hill Cottage is the exact opposite of these definitions. Four floors in total including the basement, it’s filled with hand carved furniture and architecture. I was unable to determine why the man who had it built in 1847, John Riley Robinson, called it a cottage, nor could I find any evidence that term had a different meaning in the mid-nineteenth century than it does now. In any case, it was built on a hill and did have a white oak beside it until 1890 when that tree was cut down. The property originally consisted of ten acres, but in time it was broken into plots that were sold off to others.

The museum briefly mentions John Robinson in a short video shown at the start of the guided tour. It’s no surprise that Robinson gets little attention because it’s Doctor Johannes Aten Jones and his descents who occupied the house for 101 years, and everything in it belonged to them. But the Richland County Historical Society, which runs the museum, might do well to create an exhibit about Robinson because he seems liked an interesting fellow.

Oak Hill Cottage is the exact opposite of these definitions. Four floors in total including the basement, it’s filled with hand carved furniture and architecture. I was unable to determine why the man who had it built in 1847, John Riley Robinson, called it a cottage, nor could I find any evidence that term had a different meaning in the mid-nineteenth century than it does now. In any case, it was built on a hill and did have a white oak beside it until 1890 when that tree was cut down. The property originally consisted of ten acres, but in time it was broken into plots that were sold off to others.

The museum briefly mentions John Robinson in a short video shown at the start of the guided tour. It’s no surprise that Robinson gets little attention because it’s Doctor Johannes Aten Jones and his descents who occupied the house for 101 years, and everything in it belonged to them. But the Richland County Historical Society, which runs the museum, might do well to create an exhibit about Robinson because he seems liked an interesting fellow.

He was involved in all sorts of businesses including serving as the superintendent of the Mansfield & Sandusky City Railroad by which the was built. Robinson was also the proprietor of a flour mill and had connections with Wells Fargo. Although born in Connecticut in 1810, he opposed Lincoln going to war with the Confederate states. The bankruptcy of his railroad forced him to lose his Oak Hill Cottage to the Farmer’s Bank in 1861. Afterward he headed west, then traveled south to Batopilas, Mexico, where he ran a successful silver mine. This restored his fortune, and by the time he died in 1891, he was considered the richest man in Maryland.

After he lost the cottage, it was purchased by Harvey Hall, who sold it to Doctor Jones in 1864. The latter was a vertically challenged eye, nose and ear specialist who didn’t have a local practice but rather was a traveling physician. Before arriving at a town or city, where he usually rented a storefront or hotel rooms to serve as his office, he would put ads in the newspapers that he would arrive soon. It was during a visit to Mansfield that he treated Amanda Barr and, through her, met her younger sister, the seventeen-year-old Frances Ida Barr. Doctor Jones was thirty-one at the time, but such age gaps didn’t raise eyebrows in that era.

After he lost the cottage, it was purchased by Harvey Hall, who sold it to Doctor Jones in 1864. The latter was a vertically challenged eye, nose and ear specialist who didn’t have a local practice but rather was a traveling physician. Before arriving at a town or city, where he usually rented a storefront or hotel rooms to serve as his office, he would put ads in the newspapers that he would arrive soon. It was during a visit to Mansfield that he treated Amanda Barr and, through her, met her younger sister, the seventeen-year-old Frances Ida Barr. Doctor Jones was thirty-one at the time, but such age gaps didn’t raise eyebrows in that era.

Their first child was Ida. Born in 1864, she married Lucius Elliott from Racine, Wisconsin, then divorced him twenty years later at which point she and her daughters moved into Oak Hill. Here Ida lived for the remainder of her life. The next child born was Madelle. In 1905, she met widower George Widenmayer on a cruise, fell in love, and married him. She settled with him in Newark, New Jersey, where her new husband ran a brewery. The third daughter in age was Besse. Considered the adventuresome one, according to an information sign, “she moved to Honolulu in 1915, and at the age of 45 married Lewis Churchill King in 1921.” Upon his death in 1939, she moved to Hollywood where she played bit parts in movies.

The youngest daughter, Leile, was the family’s artist. Many of her paintings are still on the walls, and they are quite good. The information sign doesn’t mention her marriage but does say her married name was Barrett. She moved back into the house in 1943 and lived there until 1965 when she sold it and all its contents to the Richland Historical Society so they could make it in a museum. She died the next year at the age of eighty-three.

The youngest daughter, Leile, was the family’s artist. Many of her paintings are still on the walls, and they are quite good. The information sign doesn’t mention her marriage but does say her married name was Barrett. She moved back into the house in 1943 and lived there until 1965 when she sold it and all its contents to the Richland Historical Society so they could make it in a museum. She died the next year at the age of eighty-three.

I visited the museum on a rainy November day, allowing me to experience something few other museums offer: the sort of lightning one experienced in the nineteenth century. Nearly all the house’s lights are no brighter than the gas ones the house once used, and they even flickered. The poor illumination left many rooms dim if not outright dark, and I worried that my photos wouldn’t come out because flashes are forbidden. (This is fine—I never use them anyway because they wash out photos.) Fortunately my camera was up to the task, and I got enough good ones for use in this travel log.

After brief foray on a side porch, the guided tour begins in the parlor, which is by far the largest room in the house. It was only used for entertaining and special occasions such as weddings. At least two if not all the daughters married here. Ida certainly did, and both her granddaughter and great-granddaughter used her wedding dress. This is the sort of thing I support because I’m no fan of the wedding-industrial complex. The parlor was probably used during a visit by one of President Wilson’s daughters during World War I. When not being employed, its furniture was draped in sheets to keep off the dust.

A frequent visitor to the house as a child was Louis Bromfield, who later went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for his novel Early Autumn. Oak Hill Cottage is the inspiration for “Shane’s Castle” in his novel The Green Bay Tree, which gave the Friends of the Libraries U.S.A. an excuse to make it a Literary Landmark in 2000. Bromfield later bought Happy Farm, which he renamed Malabar Farm after the Malabar Coast in India. Now a museum and working farm, it’s about twenty-two minutes south of Oak Hill Cottage by car and well worth visiting.

After brief foray on a side porch, the guided tour begins in the parlor, which is by far the largest room in the house. It was only used for entertaining and special occasions such as weddings. At least two if not all the daughters married here. Ida certainly did, and both her granddaughter and great-granddaughter used her wedding dress. This is the sort of thing I support because I’m no fan of the wedding-industrial complex. The parlor was probably used during a visit by one of President Wilson’s daughters during World War I. When not being employed, its furniture was draped in sheets to keep off the dust.

A frequent visitor to the house as a child was Louis Bromfield, who later went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for his novel Early Autumn. Oak Hill Cottage is the inspiration for “Shane’s Castle” in his novel The Green Bay Tree, which gave the Friends of the Libraries U.S.A. an excuse to make it a Literary Landmark in 2000. Bromfield later bought Happy Farm, which he renamed Malabar Farm after the Malabar Coast in India. Now a museum and working farm, it’s about twenty-two minutes south of Oak Hill Cottage by car and well worth visiting.

Oak Hill Cottage is typical of an upper middleclass dwelling in that its first floor has a sitting room, a library, a dining room, a pantry, and a kitchen. The second floor has three bedrooms, one nursery, a large hall, and the claustrophobic servant’s quarters. At the far end of the second floor hall is a chapel complete with a large stained glass window. The Jones family were Congregationalists, the religion created by the Puritans, so the motifs are simple and glass has no images.

I have little interest in architecture or furniture other than I can admire an exceptional example. One such piece can be found in the bedroom that belonged to Francis Jones. Within is a massive hand made half-canopy bed said to have been a replica of the one that Marie Antoniette slept in. In the room designated as the “Girls’ Bedroom” you will see Ida’s aforementioned wedding dress placed behind bulletproof glass. Well, probably not bulletproof, but it’s well sealed.

Being a well-off family, the Jones also owned their own horses and vehicles, and these were kept in the family’s carriage house, which is across the street from the house’s northern side. At one point the carriage house was converted into a home, but the Richland Historical Society has been restoring it to its original state over the years and now uses it as its headquarters. We didn’t get to go inside.

We were allowed to go the cottage’s top floor, the attic, which is rare for old houses made into museums. Most of them use the top floor for storage or offices. Now this is an interesting place. When you reach it, it’s empty save for a door on either side of the room. On its far side the floor stops abruptly and beyond is an open chasm where you can see the chapel’s stained glass window. Behind the doors are spaces filled with items put into storage by the family, which, had we had a chance to rifle through them, probably would’ve been fascinating. The floor has an alarming creak to it, although we were assured was perfectly safe. Interestingly, said creak wasn’t there before the Covid Pandemic. The theory is that when the house was shut for eighteen months, the floor dried out.🕜

I have little interest in architecture or furniture other than I can admire an exceptional example. One such piece can be found in the bedroom that belonged to Francis Jones. Within is a massive hand made half-canopy bed said to have been a replica of the one that Marie Antoniette slept in. In the room designated as the “Girls’ Bedroom” you will see Ida’s aforementioned wedding dress placed behind bulletproof glass. Well, probably not bulletproof, but it’s well sealed.

Being a well-off family, the Jones also owned their own horses and vehicles, and these were kept in the family’s carriage house, which is across the street from the house’s northern side. At one point the carriage house was converted into a home, but the Richland Historical Society has been restoring it to its original state over the years and now uses it as its headquarters. We didn’t get to go inside.

We were allowed to go the cottage’s top floor, the attic, which is rare for old houses made into museums. Most of them use the top floor for storage or offices. Now this is an interesting place. When you reach it, it’s empty save for a door on either side of the room. On its far side the floor stops abruptly and beyond is an open chasm where you can see the chapel’s stained glass window. Behind the doors are spaces filled with items put into storage by the family, which, had we had a chance to rifle through them, probably would’ve been fascinating. The floor has an alarming creak to it, although we were assured was perfectly safe. Interestingly, said creak wasn’t there before the Covid Pandemic. The theory is that when the house was shut for eighteen months, the floor dried out.🕜

This bed is based on one that Marie Antoinette slept in.

The reason Doctor Jones chose to buy Oak Hill Cottage was because his new wife had always admired it from afar. As a medical specialist, Doctor Jones was firmly in the upper middle class if not upper class, so he certainly had the money to buy the house and introduce upgrades such as gas lighting and marble fireplaces. Francis Ida was an enthusiastic wall paperer, so much so that when the house was restored, layers upon layers of it were peeled off the walls and even from the ceiling! Remnants of a variety of wallpaper rolls were found in storage.

The couple had four daughters who lived and at least one who didn’t. While in De Moines, Iowa, Doctor Jones and Francis Ida had with them their four-month-old daughter, and here she died. Because Jones had come to offer his services as a doctor, it wasn’t practicable for he and his wife to return home right away to bury their daughter, so they had her embalmed and put into a sealed iron coffin. They buried her a few months later.

The couple had four daughters who lived and at least one who didn’t. While in De Moines, Iowa, Doctor Jones and Francis Ida had with them their four-month-old daughter, and here she died. Because Jones had come to offer his services as a doctor, it wasn’t practicable for he and his wife to return home right away to bury their daughter, so they had her embalmed and put into a sealed iron coffin. They buried her a few months later.