Oberlin Heritage Center

Monroe House (Museum Entrance)

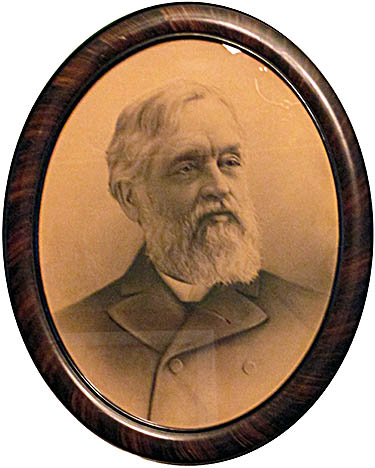

James Monroe

Guided tours are tricky things. Done right, they can really bring life into the place you are visiting. Done wrong and they can bore you to tears. Nothing is worse than a tour of a historical place that has gone wrong. Back in the early nineties I recall going through a plantation house in Virginia where the guide spent the whole time talking about different architectural features she pointed to with a large spoon. Another tour gone wrong involved a detailed account of where the dinnerware came from and its unique characteristics.

Fortunately the one I took at the Oberlin Heritage Center (OHC) in Oberlin, Ohio, was top notch. I specifically took the full tour that included three buildings: the Monroe House, a one-room school, and the Jewett House. Confined mainly indoors, this was just one of many tours the OHC offers. Others include tablet tours, bus tours (so long as you provide the vehicle), and a wide variety of walking tours such as “Scholars and Settlers History Walk” and “I Spy Oberlin: History and Architecture Scavenger Hunt.” Those who wish to avail themselves of one of these tours need to go to the front of the Monroe House where, after ringing a bell to get in, you will head to the modest gift shop.

Fortunately the one I took at the Oberlin Heritage Center (OHC) in Oberlin, Ohio, was top notch. I specifically took the full tour that included three buildings: the Monroe House, a one-room school, and the Jewett House. Confined mainly indoors, this was just one of many tours the OHC offers. Others include tablet tours, bus tours (so long as you provide the vehicle), and a wide variety of walking tours such as “Scholars and Settlers History Walk” and “I Spy Oberlin: History and Architecture Scavenger Hunt.” Those who wish to avail themselves of one of these tours need to go to the front of the Monroe House where, after ringing a bell to get in, you will head to the modest gift shop.

The tour my traveling companion and I took is about more than just those who lived there. It covers Oberlin’s history from its beginning until about the start of the twentieth century. And history is something Oberlin has much of. It began as the Oberlin Collegiate Institution, a center of higher learning that would be Ohio’s first school that award women bachelor degrees. It admitted men, women, whites and blacks and taught them in integrated classes. Founded by Reverend Jay Shepherd and Philo Stewart, those who chose to live here had to sign the Covenant of the Oberlin Colony. Although this document did not establish a communal society where all property was shared—Zoar Village being a good example of this sort of thing—it did call for limitations on what one owned and how much money one kept for oneself, though this bit was so vague there was surely much debate on what constituted enough. Tobacco and alcohol were forbidden save for medicinal purposes, as was tea, coffee, and “everything expensive that is simply calculated to gratify appetite.” The colonists’ original diet was so limited they couldn’t get the daily calories needed to construct an entire community from scratch, so the dietary restrictions were eased up.

Unlike most other Protestant religious communities founded in America, Oberlin welcomed people of other faiths. Its fierce opposition to slavery and open-mindedness about education attracted many outsiders, including abolitionist James Monroe, a Quaker who built the house that now bears his name. Although abolitionists such as Monroe all agreed that slavery was wrong and needed to end, not all were as open-minded. Most did not think blacks were equal to whites politically or biologically, and some wanted to send the whole lot back to Africa. Monroe was on the enlightened side of the abolitionist movement. He believed blacks and whites were equal in all ways and he had close black friends. While traveling with one African American friend, Monroe insisted on suffering any indignities inflicted upon him because of his race. If, for example, his friend had sleep in a barn instead of as a guest in the house, Monroe would do the same.

Unlike most other Protestant religious communities founded in America, Oberlin welcomed people of other faiths. Its fierce opposition to slavery and open-mindedness about education attracted many outsiders, including abolitionist James Monroe, a Quaker who built the house that now bears his name. Although abolitionists such as Monroe all agreed that slavery was wrong and needed to end, not all were as open-minded. Most did not think blacks were equal to whites politically or biologically, and some wanted to send the whole lot back to Africa. Monroe was on the enlightened side of the abolitionist movement. He believed blacks and whites were equal in all ways and he had close black friends. While traveling with one African American friend, Monroe insisted on suffering any indignities inflicted upon him because of his race. If, for example, his friend had sleep in a barn instead of as a guest in the house, Monroe would do the same.

Being a hub of several Underground Railroad routes, Oberlin became home to both free blacks and their fugitive slave brethren. One of the latter category was John Price, a man well known around town who for two years made a living by hiring himself out. On the morning on September 13, 1858, Shakespeare Boynton—the son of a local landowner—offered to hire Price as a field hand. Price agreed and got into his new employer’s buggy. It was a trick. Before long he was seized by a slave catcher posse headed by Anderson Jennings, the neighbor of Price’s owner in Kentucky. Knowing that keeping Price in Oberlin would not be a wise choice, the slave catchers took him eighteen miles south and imprisoned him in the Wadsworth House hotel in Wellington, Ohio.

At this time the Fugitive Slave Act was law, meaning that state and local officials were required to assist slave catchers. Fortunately civil disobedience in the face of unfair and immoral laws is a characteristic Americans have in excess, explaining why a biracial crowd of about 300 from Oberlin and Wellington surrounded the hotel demanding Price’s release. Three of their number, O.B. Wall, John Watson, and Charles Langston, tried free Price by convincing one of the captors, Jacob Lowe, to let Price go. They also asked a judge to issue a writ of habeas corpus, and tried to get the local constable to arrest the slave catchers for kidnapping. When none of these avenues of resolve bore fruit, some in the crowd barged into the hotel and freed Price, who was stashed away in the attic.

At this time the Fugitive Slave Act was law, meaning that state and local officials were required to assist slave catchers. Fortunately civil disobedience in the face of unfair and immoral laws is a characteristic Americans have in excess, explaining why a biracial crowd of about 300 from Oberlin and Wellington surrounded the hotel demanding Price’s release. Three of their number, O.B. Wall, John Watson, and Charles Langston, tried free Price by convincing one of the captors, Jacob Lowe, to let Price go. They also asked a judge to issue a writ of habeas corpus, and tried to get the local constable to arrest the slave catchers for kidnapping. When none of these avenues of resolve bore fruit, some in the crowd barged into the hotel and freed Price, who was stashed away in the attic.

Thirty-seven people were arrested for violating the Fugitive Slave Act. The State of Ohio countered by charging the slave catchers with kidnapping, though these were dropped. Of those who stormed the hotel, only one white man, Simeon Bushnell, and one black man, Charles Langston, went to trial. Both were found guilty, though their sentences were hardly punitive: Bushnell served sixty days, Langston thirty. Price fled to Canada where, according to one account, he died shortly thereafter. The incident became known as the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue. At least one those who participated in the event, Lewis Sheridan Leary, died a few years later in John Brown’s ill-fated raid on Harpers Ferry.

Upon leaving the Monroe House, the tour guide led us to Oberlin’s oldest building, a one room schoolhouse built in 1836–1837. Here whites and black children and young adults were educated together in violation of “Black Code” laws. Had those laws not existed, the integration of races was nonetheless a radical idea for this period in American history.

From here we went to the Jewett House, a large Victorian-style affair built in 1884. The Jewett family, which hailed from Massachusetts, strongly believed in temperance and abolitionism starting at least as far back as Dr. Charles Jewett and his wife, Lucy Adams Tracy, who married on September 21, 1811. When the Civil War broke out, three out of Charles’ four sons enlisted in the Union Army. The youngest, Frank, was seventeen at the time, busy teaching, and discouraged by his father to take up the cause because his father felt sending three sons—John, Richard and Charles, Jr.—off to war was enough. John was killed at Chickamauga and other two were both badly wounded.

Upon leaving the Monroe House, the tour guide led us to Oberlin’s oldest building, a one room schoolhouse built in 1836–1837. Here whites and black children and young adults were educated together in violation of “Black Code” laws. Had those laws not existed, the integration of races was nonetheless a radical idea for this period in American history.

From here we went to the Jewett House, a large Victorian-style affair built in 1884. The Jewett family, which hailed from Massachusetts, strongly believed in temperance and abolitionism starting at least as far back as Dr. Charles Jewett and his wife, Lucy Adams Tracy, who married on September 21, 1811. When the Civil War broke out, three out of Charles’ four sons enlisted in the Union Army. The youngest, Frank, was seventeen at the time, busy teaching, and discouraged by his father to take up the cause because his father felt sending three sons—John, Richard and Charles, Jr.—off to war was enough. John was killed at Chickamauga and other two were both badly wounded.

After several years of globetrotting, Frank settled down in Oberlin to become a professor of mineralogy, chemistry, physiology and—get this—English composition. After the house that bares the Jewett family name was built in 1884, Frank and his wife, Sarah Frances Gulick, moved in. Called Fanny by family members, his wife was born in Micronesia, a collection of 600 islands in the Western Pacific. The daughter of missionaries, she spent most of her childhood in Hawaii. Lake Erie College in Painseville, Ohio, served as the place for her higher education. Deciding to teach, in 1880 she moved to Japan where her father was translating the Bible into Japanese. There she met Frank, who she married that same year in Yokohama.

Fanny was a prolific author of textbooks mainly about health and hygiene that sold over six million copies. She also gave lectures, one of them being the must-see “The Dangers of the Housefly.” As part of the Progressive Movement, several of the ideas she promoted have become staples of America: clean cities, proper nutrition (which the U.S. government promotes even if far too many people ignore it), food inspection, and keeping disease-carrying flies and mosquitos under control. Less successful was her opposition to tobacco use and spitting. In 1893 she and her husband helped find the Anti-saloon League, whose goal of ridding America of alcohol succeeded with the passing of the twenty-first amendment, then fizzled out when Americans made it clear they wanted to drink alcoholic beverages. Oberlin was a bit behind on repealing Prohibition: it did not allow the sale of hard liquor in restaurants until the until the 1980s.

Fanny was a prolific author of textbooks mainly about health and hygiene that sold over six million copies. She also gave lectures, one of them being the must-see “The Dangers of the Housefly.” As part of the Progressive Movement, several of the ideas she promoted have become staples of America: clean cities, proper nutrition (which the U.S. government promotes even if far too many people ignore it), food inspection, and keeping disease-carrying flies and mosquitos under control. Less successful was her opposition to tobacco use and spitting. In 1893 she and her husband helped find the Anti-saloon League, whose goal of ridding America of alcohol succeeded with the passing of the twenty-first amendment, then fizzled out when Americans made it clear they wanted to drink alcoholic beverages. Oberlin was a bit behind on repealing Prohibition: it did not allow the sale of hard liquor in restaurants until the until the 1980s.

While in Germany attending the University of Göttingen, Frank got to know Professor Friedrich Wöhler, the first person to create a pure sample of aluminum. The was important because aluminum, though well known, was notoriously difficult to separate from other substances. While teaching chemistry, Frank told his students: “If anyone should invent a process by which aluminum could be made on a commercial scale, not only would he be a benefactor to the world, but would also lay up himself a great fortune.”

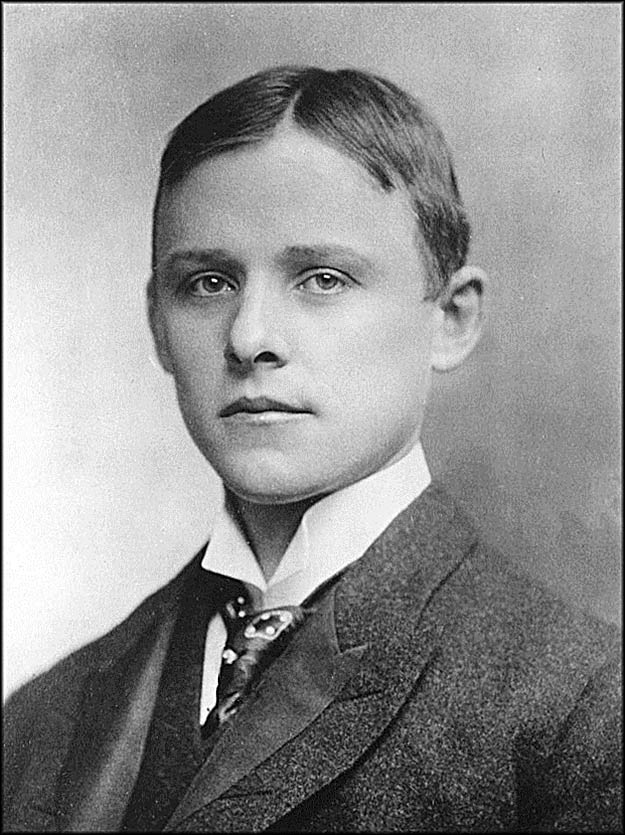

One student he mentored, Charles Martin Hall, succeeded in doing so. On February 23, 1886, he extracted pure aluminum from oxide ore using an electrochemical process that is well beyond the understanding of this writer, so those interested in how it was done can read the details here. Hall was just twenty-two when he discovered the process in his family woodshed with the assistance of his sister, Julia. A replica of the woodshed laboratory (if you can call it that) is found at the Jewett House, although the original was located at Hall’s family home. Within are two manikins representing Charles and Julia that are notorious for causing small children to cry and scaring people in general. The guide “warned” us about them before entering for that reason.

One student he mentored, Charles Martin Hall, succeeded in doing so. On February 23, 1886, he extracted pure aluminum from oxide ore using an electrochemical process that is well beyond the understanding of this writer, so those interested in how it was done can read the details here. Hall was just twenty-two when he discovered the process in his family woodshed with the assistance of his sister, Julia. A replica of the woodshed laboratory (if you can call it that) is found at the Jewett House, although the original was located at Hall’s family home. Within are two manikins representing Charles and Julia that are notorious for causing small children to cry and scaring people in general. The guide “warned” us about them before entering for that reason.

Charles Martin Hall

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

While Frank’s prophecy that the person who developed the process to separate aluminum from other compounds would become wealthy did come true, it took effort on Hall’s part to get there. His application for several patents on July 9, 1886, was delayed because a scientist in France named Paul L.T. Héroult had already applied for one using a similar process. Ignorant of Héroult’s research, Hall was granted his patents on April 2, 1889. To monetize his discovery, Hall needed investors, and these were not exactly knocking on his door. It was not until Summer 1889 that a group from Pittsburgh headed by Alfred Hunt put up the capital to start the Pittsburgh Reduction Company using Hall’s process. This company evolved into the mighty ALCOA and made Hall very rich. He spent much of his fortune supporting educational institutions and, upon his death in 1914, left nearly one-third to Oberlin College.🕜

Inside the Monroe House

Schoolhouse

Jewett House

Inside the Jewett House

Dictaphone (Inside the Jewett House)

Amazingly this phone in the Jewett House still works. While you cannot dial out, it will receive calls. The tour guide called and I dutifully answered, “Joe’s Bar and Grill.” I don’t think she was amused.

Replica of Charles Martin Hall’s woodshed workshop complete with manikins that freak people out.