Old Economy Village

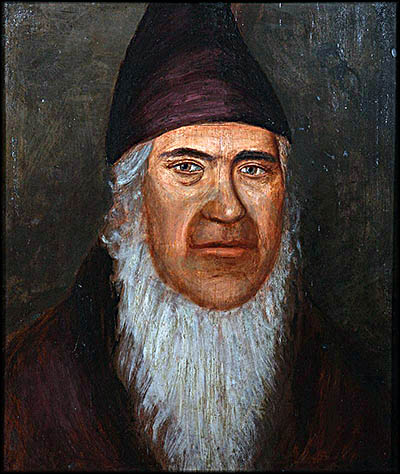

Phineas Staunton. George Rapp.

1835. National Archives.

1835. National Archives.

Visitor's Center

Inside the Feast House

Economy Church (now a Lutheran Congregation)

Ambridge, Pennsylvania, looks like your typical industrial town along the Ohio River. About half an hour drive northwest of Pittsburgh, if you just passed through, there is nothing obvious about its remarkable history. Within its borders is the remains Economy, which was founded by the Harmony Society in 1825. It’s now an historical site known as Old Economy Village.

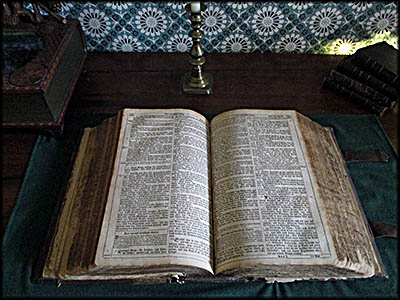

To trace the Harmony Society’s roots and why it built Economy, it’s first necessary to travel back in time to 1757 to the town of Iptingen in the Duchy of Württemberg, which is now a part of modern Germany. Here was born Johannes Georg Rapp. The son of a grape grower and farmer, he was educated in the town’s school and trained as a vine dresser and linen weaver. During his twenties while suffering from a prolonged illness, he spent his time reading the Bible that inspired a religious awakening in him.

He embraced Radical Pietism, not something the Lutheran Church to which he belonged taught. Pietism focused on inner spiritualism, charity, and mysticism, much of it based on the Book of Revelation. Its practitioners had little interest in traditional rituals and sacraments and believed the end of the world was near. Those who embraced Pietism were anabaptists, meaning they practiced adult baptism. Adherents of Pietism usually read the Berlenberg Bible, a work written in German filled with commentary that provided guidance for adherents of this theology.

Upon getting well, Rapp began preaching his new-found beliefs, drawing in quite a few followers. One was Frederick Reichert, a painter and stone mason who Rapp formally adopted as his son. (Rapp also had three natural children with his wife Christina Benzinger.) Rapp founded the Harmony Society in 1785, and in 1787 started a formal congregation that he claimed attracted ten thousand people. Unfortunately for him, religious freedom didn’t exist in Württemberg. The Lutheran Church investigated and tried him several times. At one of the trials he declared, “I am a prophet and called to be one.”

To trace the Harmony Society’s roots and why it built Economy, it’s first necessary to travel back in time to 1757 to the town of Iptingen in the Duchy of Württemberg, which is now a part of modern Germany. Here was born Johannes Georg Rapp. The son of a grape grower and farmer, he was educated in the town’s school and trained as a vine dresser and linen weaver. During his twenties while suffering from a prolonged illness, he spent his time reading the Bible that inspired a religious awakening in him.

He embraced Radical Pietism, not something the Lutheran Church to which he belonged taught. Pietism focused on inner spiritualism, charity, and mysticism, much of it based on the Book of Revelation. Its practitioners had little interest in traditional rituals and sacraments and believed the end of the world was near. Those who embraced Pietism were anabaptists, meaning they practiced adult baptism. Adherents of Pietism usually read the Berlenberg Bible, a work written in German filled with commentary that provided guidance for adherents of this theology.

Upon getting well, Rapp began preaching his new-found beliefs, drawing in quite a few followers. One was Frederick Reichert, a painter and stone mason who Rapp formally adopted as his son. (Rapp also had three natural children with his wife Christina Benzinger.) Rapp founded the Harmony Society in 1785, and in 1787 started a formal congregation that he claimed attracted ten thousand people. Unfortunately for him, religious freedom didn’t exist in Württemberg. The Lutheran Church investigated and tried him several times. At one of the trials he declared, “I am a prophet and called to be one.”

Briefly imprisoned, upon his release he was told stop preaching, but he didn’t. He looked to relocate to a different country, and after considering a few places, settled upon the United States. In 1803, he and a few others went to America, the rest following the next year. Rapp Americanized his name to George Rapp. Many Harmonists Anglicized their names as well, but despite this nod to their new homeland, nearly all of them only spoke the Swabian dialect of German and never learned English.

Rapp bought land in Pennsylvania’s Butler County where he and about 500 followers began building a farming community in 1805. This they named Harmony after the Pietist term harmonie, which, according to the book Old Economy Village, was “to live in peace and harmony with oneself, one’s fellow man, and one’s God.” Those who belonged to Harmony Society were pacifists.

They were also communists long before Marx published Communist Manifesto, which brought a more political meaning to the term. In 1805, the Harmonists gave all their property to the Society, which would in turn provide for all their needs. To make it legal and binding, they signed the “Articles of Association of the Harmony Society.” This was secular rather than religious document.

Rapp bought land in Pennsylvania’s Butler County where he and about 500 followers began building a farming community in 1805. This they named Harmony after the Pietist term harmonie, which, according to the book Old Economy Village, was “to live in peace and harmony with oneself, one’s fellow man, and one’s God.” Those who belonged to Harmony Society were pacifists.

They were also communists long before Marx published Communist Manifesto, which brought a more political meaning to the term. In 1805, the Harmonists gave all their property to the Society, which would in turn provide for all their needs. To make it legal and binding, they signed the “Articles of Association of the Harmony Society.” This was secular rather than religious document.

The desire to live communally was inspired by the churches established by Saint Paul, where everything was shared equally and no one owned personal property. One reason these early Christians did this was they thought Jesus was returning in their lifetime. The Harmonists had no desire to spread communal living outside their own group, and warned others that unless they had a deep religious devotion, it wouldn’t work anyway.

Inside George Rapp House

Rapp served as the Society’s leader and would remain so until his death in 1847 at the age of eighty-nine. Accused by some of being a tyrant, he was no cult leader. His religious beliefs and deep faith were sincere. The decision to encourage celibacy among Harmonists was an idea others suggested but he implemented. Celibacy was often ignored and became a major headache for Rapp when the second generation of Harmonists began eloping, which got them banned from the Society.

The tour guides I spoke to at the village seemed to think celibacy was only a suggestion, but some of the written sources indicate it was more rigidly enforced. Clearly it was ignored enough that the Society had its own school to which children attended to the age of fourteen. If they decided not the join the Society upon becoming adults, boys received $200 and girls $100 to, according to an information sign, give them “their start in life.”

Save for Rapp, Harmonists had no servants and did all the work themselves. In 1815, the Society sold the town of Harmony to Mennonites and established a new one in Indiana where they could expand their industries and further remove themselves from the rest of the world. This they named New Harmony. Here they focused on the profitable industries of making and selling wool and cotton cloth. To that end Frederick Rapp built steam powered mills.

The tour guides I spoke to at the village seemed to think celibacy was only a suggestion, but some of the written sources indicate it was more rigidly enforced. Clearly it was ignored enough that the Society had its own school to which children attended to the age of fourteen. If they decided not the join the Society upon becoming adults, boys received $200 and girls $100 to, according to an information sign, give them “their start in life.”

Save for Rapp, Harmonists had no servants and did all the work themselves. In 1815, the Society sold the town of Harmony to Mennonites and established a new one in Indiana where they could expand their industries and further remove themselves from the rest of the world. This they named New Harmony. Here they focused on the profitable industries of making and selling wool and cotton cloth. To that end Frederick Rapp built steam powered mills.

In those days Indiana was too distant to easily get raw materials to New Harmony’s mills, and this same limitation made it difficult to get finished products to markets to the east. So in 1825, the Society sold the town to Scottish industrialist Robert Owen. It bought new land along the Ohio River in Pennsylvania and began a new town dedicated exclusively to manufacturing called Oekonomie, German for “Economy.”

Economy focused on the manufacture of wool and silk textiles, although the latter never made a profit. Starting a third town from scratch amplified old frictions and resentments towards Rapp that had been simmering since their time in New Harmony. There it has been difficult to leave the Society, but in this new location, there were many German speaking communities nearby to which disillusioned members could move.

Rapp was accused of living far better than the rest the Harmonists—remember, only he had servants—and a visit to his house in which much of the original furniture and his possessions still reside show the truth of this. One information sign noted “some members suspected that he was using the common treasury to pay personal bills.” Some Harmonists also disliked that fact any gifts given to them went to the common treasury. There was also a rumor Rapp was having an affair with a pretty young lady named Hildegard Mutchler. Though hard evidence is lacking, when she eloped to Jacob Klein in 1826, Rapp didn’t kick her out of the Society like he had others who’d done the same.

Economy focused on the manufacture of wool and silk textiles, although the latter never made a profit. Starting a third town from scratch amplified old frictions and resentments towards Rapp that had been simmering since their time in New Harmony. There it has been difficult to leave the Society, but in this new location, there were many German speaking communities nearby to which disillusioned members could move.

Rapp was accused of living far better than the rest the Harmonists—remember, only he had servants—and a visit to his house in which much of the original furniture and his possessions still reside show the truth of this. One information sign noted “some members suspected that he was using the common treasury to pay personal bills.” Some Harmonists also disliked that fact any gifts given to them went to the common treasury. There was also a rumor Rapp was having an affair with a pretty young lady named Hildegard Mutchler. Though hard evidence is lacking, when she eloped to Jacob Klein in 1826, Rapp didn’t kick her out of the Society like he had others who’d done the same.

After he announced that in the end of the world would come in mid-September 1829, Harmonists rejoiced and things calmed down for a period. But the trouble with prophecies is when they don’t come true, doubts are raised. The world didn’t end, so grumbling resumed. Then from Germany came a letter written by a Pietist named Doctor Johann George Göntgen that said an unnamed guest would be arriving in Economy who was a messiah! The person Göntgen referred to was Maximilian Bernhard Ludwig Müller, the self-styled Count Maximillian de Leon. The announcement initially excited the Harmonists, but after eighteen months when no one arrived, doubts about Rapp surfaced once more. By the summer of 1831, it seemed there would be a rebellion against his leadership.

Then in September 1831, word came that Count Leon had arrived in New York City from Germany. Leon claimed he could trace his ancestry back to Christ and that he was an alchemist who had learned the art of producing gold. (Rapp was also an alchemist.) It didn’t hurt that the count resembled the Christ figure seen in most Western European art. The count, if indeed he were even a German noble, believed that a new age was upon them in which all would share in great wealth. He certainly liked to live the high life.

President Jackson granted him permission to establish a colony in the United States. Leon and his forty followers, which included his wife as well as Dr. Göntgen, arrived in Economy on October 18. They were welcomed with a band playing. Leon was very charismatic and quickly won over many of the Harmonists. George Rapp soon took a dislike to him, and it didn’t take long before he realized the two had some serious theological differences. Nonetheless, he offered to allow the count and his followers to stay in Economy until next spring.

Many disillusioned Harmonists became followers of Count Leon. He also attracted outsiders. Frederick Rapp, meanwhile, didn’t like the count because he was a freeloader. In a short time, Leon and his followers had amassed $1,800 of debt (about $57,225 in today’s money) from Economy’s tradesmen and general store. Frederick threatened legal action if the count and his followers didn’t pay up. Although Leon offered to leave immediately, his Harmonist followers circulated a petition on January 25, 1832, calling for the Rapps to leave their leadership roles. This was made formal by Doctor Wilhelm Schmid on January 29.

Then in September 1831, word came that Count Leon had arrived in New York City from Germany. Leon claimed he could trace his ancestry back to Christ and that he was an alchemist who had learned the art of producing gold. (Rapp was also an alchemist.) It didn’t hurt that the count resembled the Christ figure seen in most Western European art. The count, if indeed he were even a German noble, believed that a new age was upon them in which all would share in great wealth. He certainly liked to live the high life.

President Jackson granted him permission to establish a colony in the United States. Leon and his forty followers, which included his wife as well as Dr. Göntgen, arrived in Economy on October 18. They were welcomed with a band playing. Leon was very charismatic and quickly won over many of the Harmonists. George Rapp soon took a dislike to him, and it didn’t take long before he realized the two had some serious theological differences. Nonetheless, he offered to allow the count and his followers to stay in Economy until next spring.

Many disillusioned Harmonists became followers of Count Leon. He also attracted outsiders. Frederick Rapp, meanwhile, didn’t like the count because he was a freeloader. In a short time, Leon and his followers had amassed $1,800 of debt (about $57,225 in today’s money) from Economy’s tradesmen and general store. Frederick threatened legal action if the count and his followers didn’t pay up. Although Leon offered to leave immediately, his Harmonist followers circulated a petition on January 25, 1832, calling for the Rapps to leave their leadership roles. This was made formal by Doctor Wilhelm Schmid on January 29.

On March 26, 1832, a vote for leadership was held. The choices were Rapp or Leon. Rapp won two-thirds of the vote, but the Harmonists who voted for Leon, 256 out of 771, decided to depart with him. They formed the Philadelphia Society and planned to start their own town called Monaca.

Legal battles erupted. Frederick Rapp issued an eviction notice to Leon and his party ordering them to vacate their lodgings on February 1, but some of Leon’s followers blocked those assigned to remove him and his people. Six rebel members also filed criminal charges against the Society.

Those departing with Leon laid claim to their share of the treasury, leading to the March 6, 1832, agreement that gave those departing $250,000 (about $ 6,432,302 in today’s money) to be paid in three installments. Leon agreed to vacate the premises in six weeks. Those who filed charges against the Society were to drop them. By the time of the last payment on March 6, 1833, the criminal charges still hadn’t been dropped, so the money was withheld.

A mob of angry former Harmonists, both rebels and those who had left the Society before Leon’s arrival, marched on George Rapp’s house intent on taking the Society’s records. They broke into a tavern and threatened to burn down Economy. They didn’t get into Rapp’s house, and in the town itself nothing worse than some fistfights erupted. Imagine how much more ugly it might have gotten had they not all been professed pacifists!

Legal battles erupted. Frederick Rapp issued an eviction notice to Leon and his party ordering them to vacate their lodgings on February 1, but some of Leon’s followers blocked those assigned to remove him and his people. Six rebel members also filed criminal charges against the Society.

Those departing with Leon laid claim to their share of the treasury, leading to the March 6, 1832, agreement that gave those departing $250,000 (about $ 6,432,302 in today’s money) to be paid in three installments. Leon agreed to vacate the premises in six weeks. Those who filed charges against the Society were to drop them. By the time of the last payment on March 6, 1833, the criminal charges still hadn’t been dropped, so the money was withheld.

A mob of angry former Harmonists, both rebels and those who had left the Society before Leon’s arrival, marched on George Rapp’s house intent on taking the Society’s records. They broke into a tavern and threatened to burn down Economy. They didn’t get into Rapp’s house, and in the town itself nothing worse than some fistfights erupted. Imagine how much more ugly it might have gotten had they not all been professed pacifists!

After a final settlement was made, Leon and his followers built Monaca as planned, which caused the Philadelphia Society to go broke. Leon promised to refill the coffers by making gold, then said he couldn’t because of the local geology. This disillusioned his followers. When he decided to introduce church rituals uncannily like those practiced by the Roman Catholic Church, most of those who belonged to the Philadelphia Society bolted. If there is one thing anabaptists of that era hated more than anything else, it was the papacy. In addition to this, Leon had legal troubles. He had been charged with conspiracy and fermenting a riot in Economy. Before his trial took place, he departed for Louisiana where he founded a colony of German-speaking followers that lasted until the Civil War.

The Schism, as it became known, nearly bankrupted the Harmony Society. Fortunately it turned out that being communists was no barrier to becoming successful capitalists. After George Rapp died in 1847, R.L. Baker (whose German name was Gottlieb Romelius Langenbacher) and Jacob Henrici took over. Baker, who controlled the Society’s money, used it to invest in Pennsylvania’s oil wells. This made the Society a fortunate. He also bought into five major railroads and purchased land that would became the town of Beaver Falls.

When Henrici died on Christmas Day 1892, the Society was down to six members. John S. Duss took over. Claiming the Society was in financial trouble, he closed Economy’s bank and began liquidating many of its assets. He sold, for example, Economy’s Berlin Iron Works to the American Bridge Company for $4 million. This company eventually took over the town and in 1902 renamed it Ambridge. Duss’s wife, Susie, became the last person to head the Society in 1903, and in 1905 she formally dissolved it. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania tried to seize its assets, but because the original Harmonists had signed a secular contract, Mr. and Mrs. Duss successfully argued in court that they were the rightful heirs to the Society’s money. Pennsylvania did get the Society’s land and buildings in 1916. From 1921 on, these became an historical site and tourist attraction.

I began my visit the Old Economy Village at its Visitor’s Center where I paid an entrance fee, watched an introductory video, and went through two exhibits. From here I walked a couple blocks to the Old Economy Village site. A few of the buildings I passed are currently private but once served as homes to members of the Society.

On site some place have guided tours while others are self-guided. Visitors might notice that many of the houses and buildings are covered by grape vines. These were installed to allow the grapes to get direct sunlight and for indirect sunlight to reflected off the bricks to make the grapes sweeter for a better wine that Society sold for a profit.

The first guided tour I took was for George Rapp’s house. Afterwards, I explored his garden, then went to see the Baker House. During this guided tour, I was also taken to the store and wine cellar. The store held no surprises, but the wine cellar was something unexpected. I envisioned it be small, dank, dark and filled with racks of wine bottles. Deep underground, it’s quite large with a half-dome ceiling high overhead. Here are huge casks in which the wine was aged. Not single wine rack or bottle is to be seen. Casks were once brought to the surface on rails moved by a pulley and chain.

Next I ventured into the community kitchen and blacksmith’s shop. The blacksmith was in that day and I had a nice chat with him, though I can’t for the life of me remember what it was about. The Granary and Warehouse were closed, and I don’t know if they’re ever open to the public. Across the street outside of the museum site is the Society’s original church, which is now Lutheran. It has a clock tower that lacks a minute hand by design. The Harmonists had believed that those working hard needn’t worry about minutes. I finished the tour in the Feast Hall in which the museum the Harmonists once ran as well as many of the paintings they’d invested in can be seen.🕜

The Schism, as it became known, nearly bankrupted the Harmony Society. Fortunately it turned out that being communists was no barrier to becoming successful capitalists. After George Rapp died in 1847, R.L. Baker (whose German name was Gottlieb Romelius Langenbacher) and Jacob Henrici took over. Baker, who controlled the Society’s money, used it to invest in Pennsylvania’s oil wells. This made the Society a fortunate. He also bought into five major railroads and purchased land that would became the town of Beaver Falls.

When Henrici died on Christmas Day 1892, the Society was down to six members. John S. Duss took over. Claiming the Society was in financial trouble, he closed Economy’s bank and began liquidating many of its assets. He sold, for example, Economy’s Berlin Iron Works to the American Bridge Company for $4 million. This company eventually took over the town and in 1902 renamed it Ambridge. Duss’s wife, Susie, became the last person to head the Society in 1903, and in 1905 she formally dissolved it. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania tried to seize its assets, but because the original Harmonists had signed a secular contract, Mr. and Mrs. Duss successfully argued in court that they were the rightful heirs to the Society’s money. Pennsylvania did get the Society’s land and buildings in 1916. From 1921 on, these became an historical site and tourist attraction.

I began my visit the Old Economy Village at its Visitor’s Center where I paid an entrance fee, watched an introductory video, and went through two exhibits. From here I walked a couple blocks to the Old Economy Village site. A few of the buildings I passed are currently private but once served as homes to members of the Society.

On site some place have guided tours while others are self-guided. Visitors might notice that many of the houses and buildings are covered by grape vines. These were installed to allow the grapes to get direct sunlight and for indirect sunlight to reflected off the bricks to make the grapes sweeter for a better wine that Society sold for a profit.

The first guided tour I took was for George Rapp’s house. Afterwards, I explored his garden, then went to see the Baker House. During this guided tour, I was also taken to the store and wine cellar. The store held no surprises, but the wine cellar was something unexpected. I envisioned it be small, dank, dark and filled with racks of wine bottles. Deep underground, it’s quite large with a half-dome ceiling high overhead. Here are huge casks in which the wine was aged. Not single wine rack or bottle is to be seen. Casks were once brought to the surface on rails moved by a pulley and chain.

Next I ventured into the community kitchen and blacksmith’s shop. The blacksmith was in that day and I had a nice chat with him, though I can’t for the life of me remember what it was about. The Granary and Warehouse were closed, and I don’t know if they’re ever open to the public. Across the street outside of the museum site is the Society’s original church, which is now Lutheran. It has a clock tower that lacks a minute hand by design. The Harmonists had believed that those working hard needn’t worry about minutes. I finished the tour in the Feast Hall in which the museum the Harmonists once ran as well as many of the paintings they’d invested in can be seen.🕜

George Rapp House

George Rapp kept a hoard of gold and silver in his basement that eventually amounted to about $510,000, which is around $1,640,237. The Society sent some of the gold to a temple in Jerusalem where it was melted down to rebuild and decorate a temple.

George Rapp's Bible Holder

Bible in George Rapp's House

Baker House

Store

Wine Cellar

Community Kitchen

Print Shop

George Rapp's Garden

Grotto in Garden