Salem Historical Society Museum

Freedom Hall

Inside Freedom Hall

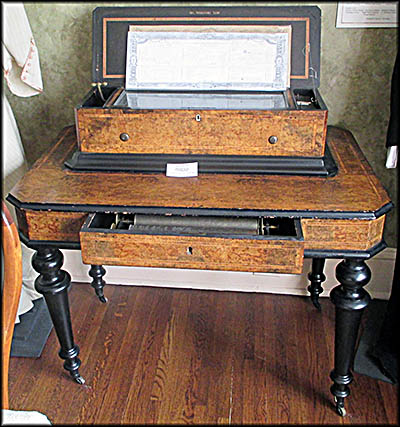

Music Box

The Salem Historical Society Museum runs a replica of this called Freedom Hall, which is a sort of oddity because most reproductions like this are built because the original is no more, but not so in this case. Now a private residence, the real Liberty Hall can be seen at 264 North Ellsworth Avenue, though remodeling over the years has made it look quite different than the museum’s version.

Freedom Hall has a reproduction of Sam Reynolds’ carpenter shop that was also used a meeting place for an organized abolitionist movement, about which more can be found in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio. In addition to other exhibits that include a 1950s barbershop and a retrospective of America’s wars and artifacts from local veterans. There is also an exhibit outlining the history of women’s suffrage, Salem being the first place in Ohio where that national movement met. On the second floor is a secret room in which slaves would have been hidden. I won’t spoil it by telling you where it is, but will report I couldn’t find it on my own.

A tour of the museum starts in the Pearce House on South Broadway Avenue that served as the residence and office for several doctors over the years. Beside it and also part of the tour is the Schell House, which was once owned by William D. Henkle, grandson of one of Salem’s cofounders. The purpose of both homes is to show how people once lived in Salem. There was, for example, a courting lamp that when lit allowed a male suitor to stay until all its oil burned out. A father not keen on who had come put far less fuel in it than someone he liked.

A tour of the museum starts in the Pearce House on South Broadway Avenue that served as the residence and office for several doctors over the years. Beside it and also part of the tour is the Schell House, which was once owned by William D. Henkle, grandson of one of Salem’s cofounders. The purpose of both homes is to show how people once lived in Salem. There was, for example, a courting lamp that when lit allowed a male suitor to stay until all its oil burned out. A father not keen on who had come put far less fuel in it than someone he liked.

Inside the Schell House

Mullins Boat

Mullins Trailer

Quaker Mule Tractor

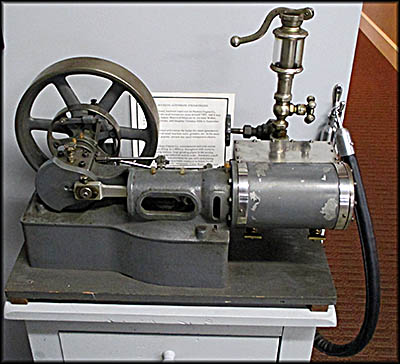

Buckeye Engine

Cabinet of Salem China

On South Lundy Avenue stands the museum’s newest building, the Dale Shaffer Research Library, whose exhibits focus mainly on Salem’s numerous former businesses and factories. Salem had an outsized industrial capacity compared to its relatively small size in large part because of its location along the railroad. In 1845, Zakok Street and Samuel Chessman helped organize the Pittsburgh & Cleveland Railroad, even taking places on its board of directors. They were understandably furious when it decided not to connect to Salem. Undaunted, they along with a number of partners raised the capital to build a rival road that would connect Pittsburgh to Rochester, New York, to New Brighton, Pennsylvania, then into Ohio where it would pass through Salem, Canton, Wooster, and Mansfield, allowing it to link up with the Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati Railroad. This venture, completed in 1852, organized as the Ohio & Pennsylvania Railroad and became part of the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1869.

Salem also had an electric trolley system. Salem Electric Railway was started Dr. J.M. Hole and his partners in 1889. It started running trolleys on May 23, 1890. Salem Electric Light & Power Company, owned by the Davis Company, took it over in 1892. It wasn’t the most robust streetcar system. One of its cars, “Old Dolly” or “Toonerville Trolley” (the latter inspired by a popular comic strip), had trouble getting to the top of Garfield Hill, a venture made harder when pranksters greased the tracks. Although profitable, fights with the city council over its license caused it to cease operation in 1912. A year later its lines were removed.

The region in which Salem stands is filled with a high-quality clay perfect for mass producing pottery and ceramics, and for a time it was a major center for this industry. In 1898 six potters started the Salem China Company to make whiteware using six kilns. After financial troubles caused by World War I, the company was taken over by F.A. Sebring in 1918, who sent out a force of twenty-five salesmen to sell its products. He invested in tunnel kilns, which send clay along a conveyor belt that have several zones of heat for better quality. The company continued to operate until 1968. Its name lived on until 2001.

The region in which Salem stands is filled with a high-quality clay perfect for mass producing pottery and ceramics, and for a time it was a major center for this industry. In 1898 six potters started the Salem China Company to make whiteware using six kilns. After financial troubles caused by World War I, the company was taken over by F.A. Sebring in 1918, who sent out a force of twenty-five salesmen to sell its products. He invested in tunnel kilns, which send clay along a conveyor belt that have several zones of heat for better quality. The company continued to operate until 1968. Its name lived on until 2001.

Probably the most diverse and innovative of all the manufacturers that once operated in Salem was the W.H. Mullins Company. One of its key products was the construction of statues made of stamped metal that looked as if they had been cast. It produced the statue of Diana designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens that once stood atop Madison Square Garden. The company was originally known as the Kittredge Cornice & Ornament Company, but when W.H. Mullins bought it out, he named it after himself. Success was not assured. The company was in debt and had to figure out how to keep its 100 workers occupied during an economic depression. It managed through all this and in time employed thousands, making a wide variety of metal items such as trailers, auto parts, metal ceilings, and even speedboats.

Many other companies, some long gone, others still in town but at some point purchased by larger firms, started in Salem. Buckeye Engine Company, which made steam engines and industrial pumps, operated from 1871 to 1920. Two stove companies, J. Woodruff and Sons and the Victor Stove Company, were here for many years. The Justice Machine Company made high end washing machines. In 1874, John Deming, who opened a store in Salem in 1862, bought a company owned by Levi Dole and Albert R. Silver that made tools for wagonmakers and blacksmiths. Rechristened the Silver and Deming Manufacturing Company, in 1890 it split in two and the part known as the Deming Company began making pumps. The Deming brand is currently produced by Crane Pump and Systems. An incomplete list of still more manufacturers that operated in Salem include Bliss, Butech, Quaker Mule Tractor, the Electric Furnace Company, Salem Tool Company, and the Major Tire & Rubber Company.🕜