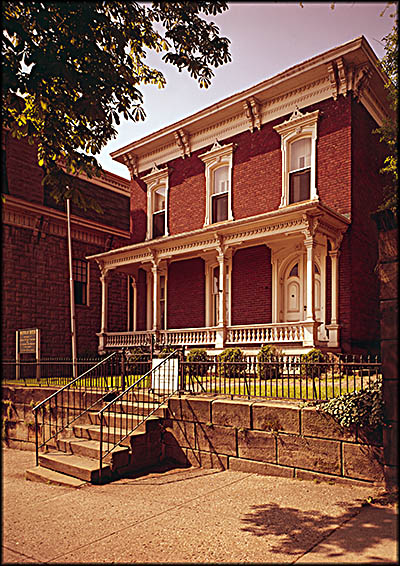

Sherman House Museum

Sherman House Museum

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

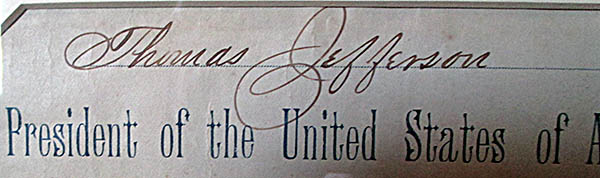

Hanging on the wall in one room is a document signed by Thomas Jefferson during his time as president.

Inside the Sherman House

Charles Sherman's Desk

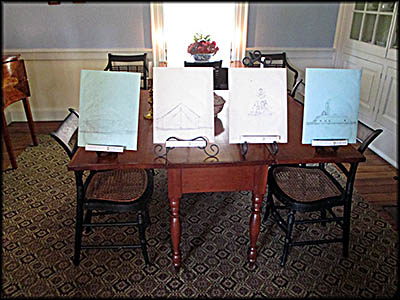

In the dining room are several sketches by William Tecumseh Sherman.

Family Photos

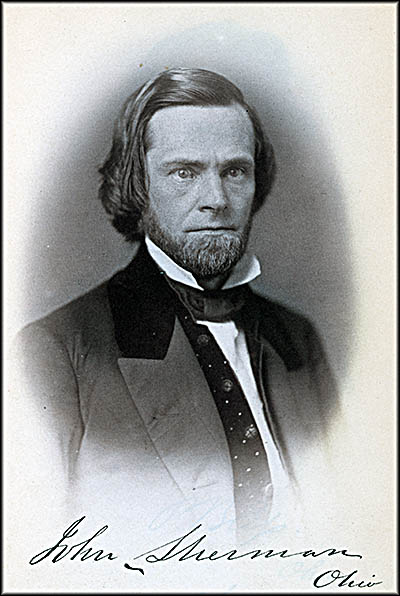

John Sherman

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

William Tecumseh Sherman

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Bedroom

Every house in Lancaster was required to possess two fire buckets.

Drawing by William Tecumseh Sherman

Cradle in which all but one of the Sherman children were rocked.

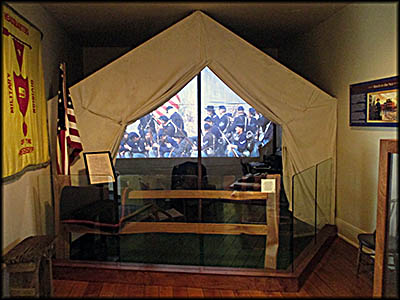

Tent Room

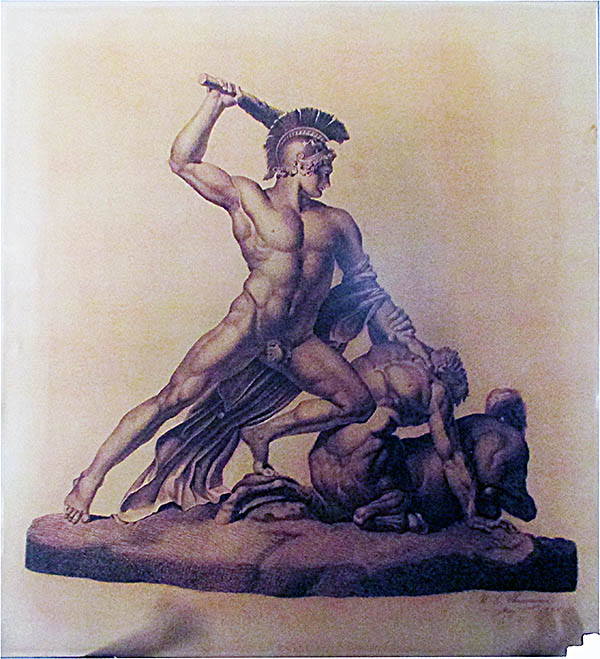

Bust of William Tecumseh Sherman

I really ought to have paid more attention to parking arrangements for the Sherman House Museum in Lancaster, Ohio, before traveling nearly two and a half hours to see it. Located on that city’s Main Street, I figured there’d be rear parking and went to around to what I thought was the museum’s rear looking for it. Failing to find it, I returned to Main Street, parallel parked, and walked to the top of the hill to cross the street at a crosswalk, it being a mighty busy thoroughfare even at noon on a Sunday.

The museum’s website does have map showing the correct lot behind the house you can park in, but this presumes you can find the unnamed alley that accesses it. Google Maps, which is usually reliable, has the house in the wrong location and doesn’t show the alley. My suggestion is if you want to visit, use the parking lot for the Mexican restaurant beside the museum, or park along the street—although most spots have a one or two hour limit save for on Sundays.

The museum offers four guided tours on the days it’s opened, and I aimed to do the earliest one, which is at noon. Although I was a tad late, no one showed up for the first tour, so I received a one-on-one tour, or rather two-on-one tour. The two tour guides working that day, a husband and wife team, seamlessly swapped their commentary while showing me around. They were, like me, history enthusiasts, and it really showed.

The museum’s website does have map showing the correct lot behind the house you can park in, but this presumes you can find the unnamed alley that accesses it. Google Maps, which is usually reliable, has the house in the wrong location and doesn’t show the alley. My suggestion is if you want to visit, use the parking lot for the Mexican restaurant beside the museum, or park along the street—although most spots have a one or two hour limit save for on Sundays.

The museum offers four guided tours on the days it’s opened, and I aimed to do the earliest one, which is at noon. Although I was a tad late, no one showed up for the first tour, so I received a one-on-one tour, or rather two-on-one tour. The two tour guides working that day, a husband and wife team, seamlessly swapped their commentary while showing me around. They were, like me, history enthusiasts, and it really showed.

Even though the museum is called the Sherman House Museum, its main focus is on Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman. In addition to two bedrooms, the upper floor has several exhibit rooms dedicated to Civil War history, one of which contains an impressive number of artifacts from that conflict. Being no expert on William Sherman’s life other than the well-know stuff such as his famous (or infamous) March to the Sea, I learned much about him that I didn’t know.

For one, friends and family called him Cump, a shortening of his middle name. He had flaming red hair, something you’d never know looking at the black and white or tinted photos of him. A cantankerous fellow, he disliked dressing up: seeing his hair and clothes anything but unkempt was unusual. Born a Presbyterian, he wasn’t baptized until the age of nine, and then it was by a Catholic priest. He married a devout Catholic (his foster sister, Ellen Ewing), and was furious when one of his sons, Thomas, became a Jesuit priest.

Despite his often disagreeable personality, he was a cultured soul. He loved theater in general and Shakespeare in particular. He was an accomplished artist, a skill at which he far exceeded his mother. He loved maps. Despite the fact that during his time as general-in-chief of the U. S. Army in 1870s and 1880s he oversaw the wars against Native Americans and their forced relocation to reservations, in 1868 he helped craft a treaty that allowed the captive Navajos (who called themselves the Diné) return to their homeland, all be it with much reduced boundaries.

For one, friends and family called him Cump, a shortening of his middle name. He had flaming red hair, something you’d never know looking at the black and white or tinted photos of him. A cantankerous fellow, he disliked dressing up: seeing his hair and clothes anything but unkempt was unusual. Born a Presbyterian, he wasn’t baptized until the age of nine, and then it was by a Catholic priest. He married a devout Catholic (his foster sister, Ellen Ewing), and was furious when one of his sons, Thomas, became a Jesuit priest.

Despite his often disagreeable personality, he was a cultured soul. He loved theater in general and Shakespeare in particular. He was an accomplished artist, a skill at which he far exceeded his mother. He loved maps. Despite the fact that during his time as general-in-chief of the U. S. Army in 1870s and 1880s he oversaw the wars against Native Americans and their forced relocation to reservations, in 1868 he helped craft a treaty that allowed the captive Navajos (who called themselves the Diné) return to their homeland, all be it with much reduced boundaries.

Cump was the son of Charles Robert Sherman, who was born in Norwalk, Connecticut, on September 26, 1788. Not long after his marriage to the artistic Mary Hoyt, he moved her and their firstborn son, Charles, to Lancaster in which he set up a law practice. Two years later the War of 1812 broke out, a conflict in which he participated as major in the Ohio Militia.

During President James Madison’s administration, he was appointed the Collector of Internal Revenue for the Third District of Ohio, and he hired two men to collect the taxes on his behalf. The trouble was most paid in local bank scrip, but the government required that all money delivered to Washington be in notes from the Bank of the United States or one of which branches, none of which were in Ohio. Charles mortgaged his house and used much of his savings to pay the money owed, putting him into some serious debt. But being a lawyer, he figured he’d be able to recoup his losses and pay off his mortgage.

He was appointed to the Ohio Supreme Court on January 11, 1823. His duties included working on a circuit court, and it was during one of these ventures he died in Lebanon of an unknown illness on June 24, 1829. He and his wife had eleven children, the youngest an infant, and because of Charles’ outstanding debt, Mary had no way to provide for all of them. Several younger ones were fostered out. Cump, aged nine, went down the street to the household of Thomas Ewing, Charles Sherman’s good friend. John, aged six, was sent to Mount Vernon to live with his father’s cousin for the next four years.

During President James Madison’s administration, he was appointed the Collector of Internal Revenue for the Third District of Ohio, and he hired two men to collect the taxes on his behalf. The trouble was most paid in local bank scrip, but the government required that all money delivered to Washington be in notes from the Bank of the United States or one of which branches, none of which were in Ohio. Charles mortgaged his house and used much of his savings to pay the money owed, putting him into some serious debt. But being a lawyer, he figured he’d be able to recoup his losses and pay off his mortgage.

He was appointed to the Ohio Supreme Court on January 11, 1823. His duties included working on a circuit court, and it was during one of these ventures he died in Lebanon of an unknown illness on June 24, 1829. He and his wife had eleven children, the youngest an infant, and because of Charles’ outstanding debt, Mary had no way to provide for all of them. Several younger ones were fostered out. Cump, aged nine, went down the street to the household of Thomas Ewing, Charles Sherman’s good friend. John, aged six, was sent to Mount Vernon to live with his father’s cousin for the next four years.

Although John’s impact on U.S. history is far less known than his older brother’s, it’s equally significant. Most U.S. history books have a chapter that talk about the rise of trusts and monopolies and how the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was designed to break them up. What these books fail to mention is that Sherman behind the act was Cump’s brother. And while the Sherman Antitrust Act wasn’t quite up to the task of reigning in the monopolies of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was the first of its kind. His contemporaries certainly didn’t realize its significance. John’s New York Times obituary from October 23, 1900, failed to mention it.

John started his political career as a Whig, then helped found the Republican Party in Ohio after the former’s implosion. A moderate, he had no interest in abolishing slavery outright. He figured keeping it from spreading would cause it to wither and die on its own. At the federal level he served for many years in the House of Representatives, and was appointed U.S. senator when Lincoln made Ohio senator Salmon P. Chase the Secretary of the Treasury. John spearheaded the legislation that allowed the federal government to issue greenbacks that weren’t redeemable for specie payments—the way the North financed the war. After the war, John stayed in Senate, although he repeatedly tried and failed to secure the Republican nomination for president. When William McKinley became president, he made John his secretary of state, but ill health forced John to resign from this post. He died on October 22, 1900.

In contrast to John, Cump, hated politics, an irony considering his foster father was a lifelong politician. Ewing used his political influence to gain Cump an appointment at West Point. Here Cump struggled with the discipline and found the courses difficult. Despite this, he graduated sixth in a class of forty-two. He would’ve been fourth, but he lost a couple slots because of an excessive number of demerits, some of them earned because he liked to cook in his dorm room notwithstanding the rule against it. Upon graduation in 1840, he decided to stay in the army despite Ewing’s objections.

John started his political career as a Whig, then helped found the Republican Party in Ohio after the former’s implosion. A moderate, he had no interest in abolishing slavery outright. He figured keeping it from spreading would cause it to wither and die on its own. At the federal level he served for many years in the House of Representatives, and was appointed U.S. senator when Lincoln made Ohio senator Salmon P. Chase the Secretary of the Treasury. John spearheaded the legislation that allowed the federal government to issue greenbacks that weren’t redeemable for specie payments—the way the North financed the war. After the war, John stayed in Senate, although he repeatedly tried and failed to secure the Republican nomination for president. When William McKinley became president, he made John his secretary of state, but ill health forced John to resign from this post. He died on October 22, 1900.

In contrast to John, Cump, hated politics, an irony considering his foster father was a lifelong politician. Ewing used his political influence to gain Cump an appointment at West Point. Here Cump struggled with the discipline and found the courses difficult. Despite this, he graduated sixth in a class of forty-two. He would’ve been fourth, but he lost a couple slots because of an excessive number of demerits, some of them earned because he liked to cook in his dorm room notwithstanding the rule against it. Upon graduation in 1840, he decided to stay in the army despite Ewing’s objections.

His early military career was neither distinctive nor, to his frustration, did it involve combat despite the fact he was serving during the Mexican-American War. After marrying, his wife pressured him to move back to Lancaster and work in a civilian job. The two were often apart because of Ellen’s insistence on living near family in Lancaster. Cump left the army in 1853 to become a banker first in San Francisco, then New York. The Panic of 1857 ended that career, and for a time he worked in law and real estate in Kansas.

From 1859 to 1861, he served as the first superintendent of the Louisiana Military Academy, which later became Louisiana State University. For the first time in his life he found a career he loved. Ellen didn’t. She and five of their children spent most of the time in Lancaster. Having spent much of his military career in the South, he came to love the region and its people. He cared little about slavery and had no desire to see it ended, but when it became apparent Louisiana would secede, he left because he refused to foreswear his allegiance to the Constitution.

After briefly serving as president of the Fifth Street Railroad in St. Louis, he received an army commission as a colonel of the Thirteenth Regular Infantry. He led his force into the First Battle of Bull Run, but the Union defeat caused him to despair. At one point his pessimism about winning the war so overwhelmed him, his commanding officer, Henry Halleck, sent him to Lancaster to recover.

Then he met Ulysses S. Grant and everything changed. He served with Grant during that latter’s capture of Forts Donelson and Henry, then at Shiloh. Sherman convinced Grant to stay in the Army despite an apparent demotion after Shiloh. About this time Sherman once joked: “Grant stood by me when I was crazy, and I stood by him when he was drunk, [and] now we stand by each other.” Vicksburg was another critical point for Sherman’s mental wellbeing because for months it seemed impossible to take, but Grant’s dogged perseverance and some brilliant generalship by Sherman resulted in its capture on July 4, 1863.

From 1859 to 1861, he served as the first superintendent of the Louisiana Military Academy, which later became Louisiana State University. For the first time in his life he found a career he loved. Ellen didn’t. She and five of their children spent most of the time in Lancaster. Having spent much of his military career in the South, he came to love the region and its people. He cared little about slavery and had no desire to see it ended, but when it became apparent Louisiana would secede, he left because he refused to foreswear his allegiance to the Constitution.

After briefly serving as president of the Fifth Street Railroad in St. Louis, he received an army commission as a colonel of the Thirteenth Regular Infantry. He led his force into the First Battle of Bull Run, but the Union defeat caused him to despair. At one point his pessimism about winning the war so overwhelmed him, his commanding officer, Henry Halleck, sent him to Lancaster to recover.

Then he met Ulysses S. Grant and everything changed. He served with Grant during that latter’s capture of Forts Donelson and Henry, then at Shiloh. Sherman convinced Grant to stay in the Army despite an apparent demotion after Shiloh. About this time Sherman once joked: “Grant stood by me when I was crazy, and I stood by him when he was drunk, [and] now we stand by each other.” Vicksburg was another critical point for Sherman’s mental wellbeing because for months it seemed impossible to take, but Grant’s dogged perseverance and some brilliant generalship by Sherman resulted in its capture on July 4, 1863.

In 1864 the war became a stalemate, and it’s Sherman who came up with the strategy to change its tide in favor of the Union. Rather than defeat Confederate armies, he thought it best to destroy the South’s ability and will to wage war with the caveat that once the South surrendered, they should be forgiven and allowed to return to the Union. After taking Atlanta in September 1864, he cut his supply lines and began a march to the sea. His troops would live off the land.

Along the way he had telegraph lines chopped down to cut off communications, heated train rails red hot, then twisted them to make them unusable (“Sherman’s neckties”), and destroyed infrastructure necessary for the Confederate war effort, such as bridges, tunnels and plantations. He burned his way to Savanna where he took Fort McAllister. From here he headed to the Carolinas where General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered to him in Durham, North Carolina.

A recreation of Sherman’s field tent is found in the museum’s Tent Room, complete with a three minute video shown at its back. The tent room is on the house’s upper floor, where visitors can also see the cradle in which both Cump and nine of his brothers and sisters once rocked. In the children’s bedroom there are artifacts such as shoes designed to be worn on either foot and the bed the children slept in. An information sign notes that the house had no closets, though my tour guides reputed that by showing me the house’s sole one in Charles Sherman’s office. Few people wanted closets in their homes at that time because they counted as rooms, which increased their property taxes.🕜

Along the way he had telegraph lines chopped down to cut off communications, heated train rails red hot, then twisted them to make them unusable (“Sherman’s neckties”), and destroyed infrastructure necessary for the Confederate war effort, such as bridges, tunnels and plantations. He burned his way to Savanna where he took Fort McAllister. From here he headed to the Carolinas where General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered to him in Durham, North Carolina.

A recreation of Sherman’s field tent is found in the museum’s Tent Room, complete with a three minute video shown at its back. The tent room is on the house’s upper floor, where visitors can also see the cradle in which both Cump and nine of his brothers and sisters once rocked. In the children’s bedroom there are artifacts such as shoes designed to be worn on either foot and the bed the children slept in. An information sign notes that the house had no closets, though my tour guides reputed that by showing me the house’s sole one in Charles Sherman’s office. Few people wanted closets in their homes at that time because they counted as rooms, which increased their property taxes.🕜