Schoenbrunn Village

Schoolhouse

Inside the Church

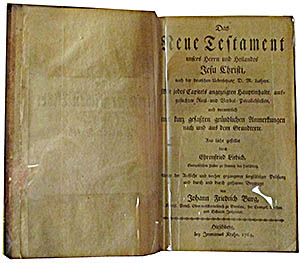

This was one of the German language Bibles on display in the museum, but I have no idea if it came from Schoenbrunn or not.

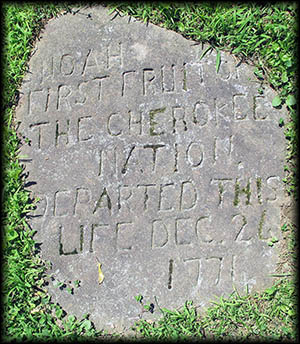

Wow, look at these old graves. They must be the oldest ones I have seen in Ohio. Except they are replicas.

In the early 1920s a Moravian minister living in Ohio, Reverend Joseph Weinland of Dover, decided someone ought to explore the lost settlement of Schoenbrunn, a place located on the outskirts of modern New Philadelphia. Weinland’s effort yielded a team of archeologists who excavated the site in the late 1920s, then built a selection of replica structures upon their original locations. Despite the fact I have serious reservations about constructing an historical site from whole clothe such as they had done, I decided to visit anyway partly because of the interesting history of the original village, but mostly because its official website (now gone) showed a variety of historical re-enactors wandering about the place, and I can’t resist a good historical re-enactment. Alas, the website didn’t quite capture the reality. Not a one of them showed up the day I visited.

Despite this, I did learn quite a bit of Schoenbrunn Village’s history. Moravian missionaries had founded this settlement as a place where they could educate and convert the native peoples of Ohio to their Protestant religion of Unitas Fratrum, or “Unity of Brethren.” This church, which began in Moravia, believed in pacifism, the singing of hymns, and the rejection of transubstantiation (the true presence of Jesus in the Eucharist), basing its core theology on the philosophy of John Hus, who thought the Bible should serve as the sole source for one’s spirituality and needed to be translated into the vernacular so all could read and understand it. The Catholic Church disagreed: it burned him at the stake for heresy. Persecution caused many of the Brethren, primarily German-speaking folk, to move out of Moravia to safer grounds, and some came to America. Here they established a number of settlements, including Nazareth and Bethlehem in Pennsylvania, and Old Salem in North Carolina.

Despite this, I did learn quite a bit of Schoenbrunn Village’s history. Moravian missionaries had founded this settlement as a place where they could educate and convert the native peoples of Ohio to their Protestant religion of Unitas Fratrum, or “Unity of Brethren.” This church, which began in Moravia, believed in pacifism, the singing of hymns, and the rejection of transubstantiation (the true presence of Jesus in the Eucharist), basing its core theology on the philosophy of John Hus, who thought the Bible should serve as the sole source for one’s spirituality and needed to be translated into the vernacular so all could read and understand it. The Catholic Church disagreed: it burned him at the stake for heresy. Persecution caused many of the Brethren, primarily German-speaking folk, to move out of Moravia to safer grounds, and some came to America. Here they established a number of settlements, including Nazareth and Bethlehem in Pennsylvania, and Old Salem in North Carolina.

The Brethren responsible for the founding of Schoenbrunn came from Pennsylvania and relocated to Ohio mainly to get away from the ongoing tensions between the Colonies and England that would soon erupt into the American Revolution. Under the leadership of Reverend David Zeisberger, they founded a new missionary settlement in Ohio’s Tuscarawas Valley where a Delaware chief, Netawates, had given Zeisberger land by a spring. Called Schoenbrunn—in German this means “a beautiful spring”—at its peak it housed around 400 white settlers and native people, the latter of whom made up the majority and were mostly Delaware, or Lenni Lenape, people. Although originally from the Atlantic coast, the Delaware had come to Ohio after being forced from their homeland by white invaders.

Founded on May 3, 1772, Schoenbrunn lasted a mere five years. Standing at crossroads used by warring British and Colonial forces, its inhabitants thought it better to leave than become entangled in what became known as the American Revolution. Before departing in April 1777, Reverend Zeisberger destroyed the village’s church to prevent others from desecrating it, then moved to Goshochgunk, now Coshocton, Ohio, near which one can visit the historic Roscoe Village.

During its Mayfly-like existence, Schoenbrunn’s school aimed to teach its white and Native American children to read and write so they could understand the Bible. And here the Brethren did something radical for the day: rather than force the Delaware children to conform to white norms, they taught them in their native language. To make this easier, Reverend Zeisberger created the spelling book Essay of a Delaware-Indian English Spelling Book for the Use of Christian Indians on Muskingum River, a remarkable achievement considering that language previously had no written form. Zeisberger also, according to a plaque in front of the replica school, “translated a dictionary, sermons, hymn books, and liturgies into the Delaware language,” an Algonquian tongue.

Despite their enlightened view when it came to education, the village’s whites appear to have treated their native neighbors as second-class citizens. Why this conclusion? Because the only replica native houses in the village are small dirt floor log cabins with holes in the roofs to allow smoke to escape, while most of the much larger whites dwellings had fireplaces, wooden floors and, in a few cases, whitewash walls. The archeologists who excavated the Schoenbrunn site did so in the late 1920s, a time when most American whites viewed “Indians” as culturally and intellectually inferior. Although the village contained about sixty buildings, the archeologists only constructed a small handful, and of those, they chose to build mostly those that had belonged to the village’s white citizens, filling them with furniture and other evidence of habitation. The Delaware dwellings, in contrast, all look like hovels with no evidence of anyone having lived in them. Had this excavation occurred in the present day, one would hope more enlightened scholars would give a clearer picture of how the Delaware lived and their interaction with whites, something virtually nonexistent at present.

Founded on May 3, 1772, Schoenbrunn lasted a mere five years. Standing at crossroads used by warring British and Colonial forces, its inhabitants thought it better to leave than become entangled in what became known as the American Revolution. Before departing in April 1777, Reverend Zeisberger destroyed the village’s church to prevent others from desecrating it, then moved to Goshochgunk, now Coshocton, Ohio, near which one can visit the historic Roscoe Village.

During its Mayfly-like existence, Schoenbrunn’s school aimed to teach its white and Native American children to read and write so they could understand the Bible. And here the Brethren did something radical for the day: rather than force the Delaware children to conform to white norms, they taught them in their native language. To make this easier, Reverend Zeisberger created the spelling book Essay of a Delaware-Indian English Spelling Book for the Use of Christian Indians on Muskingum River, a remarkable achievement considering that language previously had no written form. Zeisberger also, according to a plaque in front of the replica school, “translated a dictionary, sermons, hymn books, and liturgies into the Delaware language,” an Algonquian tongue.

Despite their enlightened view when it came to education, the village’s whites appear to have treated their native neighbors as second-class citizens. Why this conclusion? Because the only replica native houses in the village are small dirt floor log cabins with holes in the roofs to allow smoke to escape, while most of the much larger whites dwellings had fireplaces, wooden floors and, in a few cases, whitewash walls. The archeologists who excavated the Schoenbrunn site did so in the late 1920s, a time when most American whites viewed “Indians” as culturally and intellectually inferior. Although the village contained about sixty buildings, the archeologists only constructed a small handful, and of those, they chose to build mostly those that had belonged to the village’s white citizens, filling them with furniture and other evidence of habitation. The Delaware dwellings, in contrast, all look like hovels with no evidence of anyone having lived in them. Had this excavation occurred in the present day, one would hope more enlightened scholars would give a clearer picture of how the Delaware lived and their interaction with whites, something virtually nonexistent at present.

The village’s cemetery, God’s Acre, has an even bigger problem. At first I found it quite thrilling to look at graves that dated from as early as 1771 until something occurred to me: why did they have their inscriptions written in English? After all, the village’s white inhabitants spoke German, not English. At the visitor’s center, I asked the only person working there if these were the original graves. She thought the ones you could barely read might be authentic, but after getting home I did some more digging and learned that the originals had had wooden markers. Thus I and anyone else visiting God’s Acre could come away thinking these tombstones first appeared in the eighteenth century whereas in reality someone put them there in the late 1920s, although the original bodies do rest underneath them.

Schoenbrunn failed in other ways as well. In its visitor’s center you will find a small museum in which a plethora of signs packed with an overwhelming amount of information. I personally think these ought to contain brief and concise intelligence, not entire essays. The museum’s artifacts, in contrast, needed better labeling. Did, for example, the old German-language Bibles on display come from the site itself, or from elsewhere? Finally, the exhibit containing manikins of a white man and a Native American working together looks cheesy and ought to go.

While those going through the museum may well find the sheer amount of text to read a bit too much, the village has the opposite problem. Just a few information plaques stand scattered about; instead, the museum hands you a poorly designed brochure filled with dense text and no map that you use as your guide, very cumbersome when you also want to take photos and explore the buildings.

Schoenbrunn failed in other ways as well. In its visitor’s center you will find a small museum in which a plethora of signs packed with an overwhelming amount of information. I personally think these ought to contain brief and concise intelligence, not entire essays. The museum’s artifacts, in contrast, needed better labeling. Did, for example, the old German-language Bibles on display come from the site itself, or from elsewhere? Finally, the exhibit containing manikins of a white man and a Native American working together looks cheesy and ought to go.

While those going through the museum may well find the sheer amount of text to read a bit too much, the village has the opposite problem. Just a few information plaques stand scattered about; instead, the museum hands you a poorly designed brochure filled with dense text and no map that you use as your guide, very cumbersome when you also want to take photos and explore the buildings.

With exception of a couple houses, the school and church, the log cabins all look pretty much the same inside and out; I quickly grew tired of trying to go inside each one. A pity, because the stories connected to them, if better conveyed to the visitor, would have made them more interesting. Take the Margaret and Richard Conner Cabin as an example. Shawnees had taken Margaret captive as a baby and raised her as one of their own. When Richard encountered her, she spoke no language other than the Shawnee’s Algonquian tongue. Deciding he wanted to marry her, Richard bargained with her Shawnee chief to purchase her for $200 and their first born child. One would think once he got away with Margaret he’d renege the latter part of the bargain, but, amazingly, he didn’t. Upon the birth of his first born, Jason, he and Margaret gave their child up as agreed, although four years later they bought him back for forty buckskins.

Now despite all my criticisms of Schoenbrunn, I don’t entirely blame the village’s problems on the Ohio History Connection (OHC), which runs it. Those currently working for and operating the OHC didn’t build this village, they just inherited it. And as a cash-starved non-profit, the OHC for the most part has to depend on volunteers for its historical re-enactors. This means that if they don’t show up (the reason we saw no one the day I visited), you don’t get to see them and it reduces your overall experience. Because of this, I recommend visiting Schoenbrunn during a scheduled event so you have something else to look at other than a repetitive collection of log cabins and some counterfeit gravestones.🕜

Now despite all my criticisms of Schoenbrunn, I don’t entirely blame the village’s problems on the Ohio History Connection (OHC), which runs it. Those currently working for and operating the OHC didn’t build this village, they just inherited it. And as a cash-starved non-profit, the OHC for the most part has to depend on volunteers for its historical re-enactors. This means that if they don’t show up (the reason we saw no one the day I visited), you don’t get to see them and it reduces your overall experience. Because of this, I recommend visiting Schoenbrunn during a scheduled event so you have something else to look at other than a repetitive collection of log cabins and some counterfeit gravestones.🕜