THE CAPTURE, TORTURE AND

ESCAPE OF SIMON KENTON

ESCAPE OF SIMON KENTON

"Young Kenton's Triumph Over His Rival"

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Frank Triplet (1885).

Digitized by Google Books.

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Frank Triplet (1885).

Digitized by Google Books.

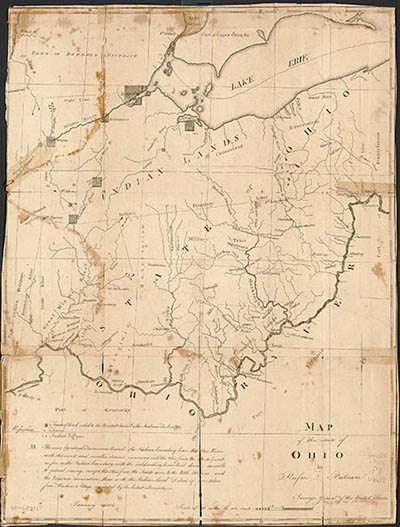

Map of the State of Ohio

Rufus Putman, Thomas Wightman, and Thaddeus Mason Harris. Boston: Manning & Loring, 1805. Library of Congress.

Rufus Putman, Thomas Wightman, and Thaddeus Mason Harris. Boston: Manning & Loring, 1805. Library of Congress.

Copyright © 2020 by Mark Strecker

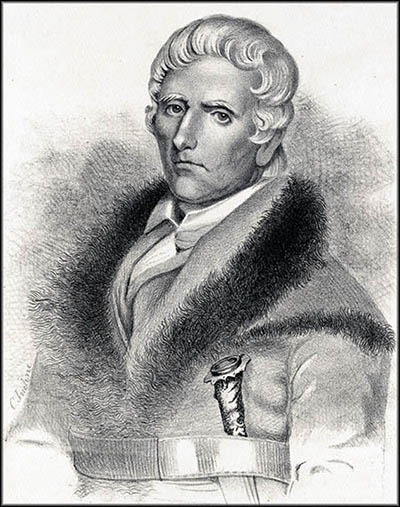

"Simon Kenton at the Age of 76"

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Frank Triplet (New York: N.D. Thompson Publishing Co., 1885). Digitized by Google Books.

Modified and enhanced by Mark Strecker.

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Frank Triplet (New York: N.D. Thompson Publishing Co., 1885). Digitized by Google Books.

Modified and enhanced by Mark Strecker.

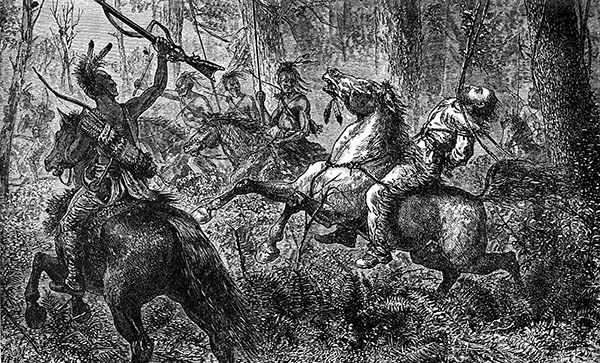

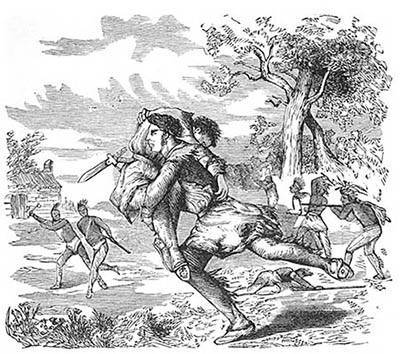

"Kenton Rescues Boone"

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Frank Triplet (New York: N.D. Thompson Publishing Co., 1885). Digitized by Google Books.

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Frank Triplet (New York: N.D. Thompson Publishing Co., 1885). Digitized by Google Books.

The Shawnee council members took up a warclub to signify their vote. Passing it on meant the prisoner would live. Striking it hard against the ground signaled death. Simon Kenton understood not a word of Algonquin, but seeing the warclub strike the ground more times than not, he knew he’d been sentenced to death. After more debate and another vote, the form of execution was decided. He would burn at the stake.

Kenton was no stranger to life threatening situations. His first such moment had occurred when he was just sixteen and living in Fauquier County, Virginia, where he was born on May 15, 1755. He’d accidentally killed a man in a fight and now he needed to flee into the wildlands of the West else he’d surely be executed for murder. (Later in life he learned the man hadn't died.) He’d gotten himself into this situation because of his adolescent lust for revenge. He was upset that Ellen Cummins, the woman he loved, had chosen to marry William Leachman, so on the day of their wedding he either challenged Leachman to a fight outside the church or confronted him during the reception. In the first case the source says Leachman beat Kenton soundly. In the second, Leachman’s brother lured Kenton outside where he and some friends beat Kenton. No matter which version is correct, the outcome was the same. Kenton wanted to fight Leachman.

As to when the fatal encounter occurred, again the two primary sources we have about Kenton differ significantly. One puts it a few days after the wedding on April 6, 1771, and the other says it was months later by which time Kenton had grown to over six feet in height and bulked up. Both sources agree he found his opponent in an isolated place, challenged him to a fight, and this time grabbed Leachman by his long hair, securing it to a sapling. With Leachman hobbled, Kenton pommeled him to the point where he spat up blood and collapsed dead. Or so Kenton thought. Thirteen years later he learned Leachman hadn’t died after all.

During his journey west, necessity taught Kenton woodcraft. Arriving along the Cheat River, which is in modern West Virginia, he acquired a rifle and became a hunter and trapper. Going by the name Simon Butler, at Fort Pitt (modern Pittsburgh) he met a woodsman named Simon Girty who became a friend and mentor. In 1774 the two fought alongside one another during Lord Dunmore’s War, a landgrab by Virginia’s governor, John Murray, Lord Dunmore.

In 1768 the Iroquois granted the British all lands east and south of the Ohio River when they signed the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. The trouble was it wasn’t theirs to give away. The Delaware, Shawnee and Mingoes considered this their land. In addition to that, a 1763 royal proclamation forbade American colonists from settling west of the Appalachian Mountains, although those already living there, mostly French subjects, could remain.

The British didn’t want colonists moving into the area because they lacked the resources to defend and govern new settlers. Any American colonist who went there was a squatter who had no legal claim to the land. One of the reasons Americans rebelled against King George III in 1775 was a frustration that all that land on the other side of the mountains couldn’t be claimed. This was one of the reasons George Washington, a major land speculator, took up the cause of independence.

In 1774, militant white settlers stirred up by a propaganda letter written by fur trader George Croghan crossed the Ohio and massacred several Mingoes along the Yellow River. Those murdered included several family members of the Mingo war chief John Logan, whose Native American names were Soyechtowa and Tocaniadorogon. Up until this time Logan had been a good friend to settlers. Enraged, he attacked colonists along the frontier. Lord Dunmore used this unrest as an excuse to launch a military expedition against the Shawnee, who had nothing to do with Logan’s attacks, forcing them to capitulate and give up some of their land.

Kenton served as a spy during this conflict. After it ended, he and Thomas Williams headed down the Ohio River to the mouth of the Big Sandy River (between modern Catlettsburg, Kentucky, and Kenova, West Virginia) where they planned to winter and hunt. Early in the spring of 1775 they found good land in a place now known as Limestone, West Virginia. Here they settled and grew some corn. In the fall Kenton ventured south and encountered Michael Stoner, who’d come west the year before with Daniel Boone. Stoner informed Kenton that there were settlements to the south in Kentucky. Kenton and Williams visited these and decided to relocate.

In 1777 the Shawnee launched three attacks against Boonesborough, the settlement founded by Daniel Boone where Kenton was then living. During the first attack, Boone and thirteen others including Kenton were caught outside the fort with the Shawnee between them and the gate. During the ensuring fight, Boone was shot in the leg, the bullet breaking his bone and forcing him to collapse onto the ground. A Shawnee warrior raised his tomahawk to end Boone’s life, but it never struck home: Kenton shot the fellow, earning Boone’s praise.

In 1778 Boone led an attack on a Shawnee village along Paint Creek. An unexpected skirmish with Shawnee warriors on the way there prompted Boone to return home because element of surprise had been lost. Kenton and another man, Alexander Montgomery, stayed behind to spy on the Paint Creek settlement. For two days they watched. Then came a chance to steal two horses, which they did, a success that gave them a taste for horse thievery.

Around September 1, 1778, Kenton, Alexander Montgomery, and the flaming red-haired George Clark (the older brother of William Clark, he of Lewis and Clark fame) headed out to spy on the Shawnee town of Chillicothe. The name meant “principal town,” a place that served as a seasonal capital. The town Kenton and Montgomery spied upon was located along the Little Miami River near Xenia, Ohio, and has no relationship to the modern Ohio town of Chillicothe.

As to when the fatal encounter occurred, again the two primary sources we have about Kenton differ significantly. One puts it a few days after the wedding on April 6, 1771, and the other says it was months later by which time Kenton had grown to over six feet in height and bulked up. Both sources agree he found his opponent in an isolated place, challenged him to a fight, and this time grabbed Leachman by his long hair, securing it to a sapling. With Leachman hobbled, Kenton pommeled him to the point where he spat up blood and collapsed dead. Or so Kenton thought. Thirteen years later he learned Leachman hadn’t died after all.

During his journey west, necessity taught Kenton woodcraft. Arriving along the Cheat River, which is in modern West Virginia, he acquired a rifle and became a hunter and trapper. Going by the name Simon Butler, at Fort Pitt (modern Pittsburgh) he met a woodsman named Simon Girty who became a friend and mentor. In 1774 the two fought alongside one another during Lord Dunmore’s War, a landgrab by Virginia’s governor, John Murray, Lord Dunmore.

In 1768 the Iroquois granted the British all lands east and south of the Ohio River when they signed the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. The trouble was it wasn’t theirs to give away. The Delaware, Shawnee and Mingoes considered this their land. In addition to that, a 1763 royal proclamation forbade American colonists from settling west of the Appalachian Mountains, although those already living there, mostly French subjects, could remain.

The British didn’t want colonists moving into the area because they lacked the resources to defend and govern new settlers. Any American colonist who went there was a squatter who had no legal claim to the land. One of the reasons Americans rebelled against King George III in 1775 was a frustration that all that land on the other side of the mountains couldn’t be claimed. This was one of the reasons George Washington, a major land speculator, took up the cause of independence.

In 1774, militant white settlers stirred up by a propaganda letter written by fur trader George Croghan crossed the Ohio and massacred several Mingoes along the Yellow River. Those murdered included several family members of the Mingo war chief John Logan, whose Native American names were Soyechtowa and Tocaniadorogon. Up until this time Logan had been a good friend to settlers. Enraged, he attacked colonists along the frontier. Lord Dunmore used this unrest as an excuse to launch a military expedition against the Shawnee, who had nothing to do with Logan’s attacks, forcing them to capitulate and give up some of their land.

Kenton served as a spy during this conflict. After it ended, he and Thomas Williams headed down the Ohio River to the mouth of the Big Sandy River (between modern Catlettsburg, Kentucky, and Kenova, West Virginia) where they planned to winter and hunt. Early in the spring of 1775 they found good land in a place now known as Limestone, West Virginia. Here they settled and grew some corn. In the fall Kenton ventured south and encountered Michael Stoner, who’d come west the year before with Daniel Boone. Stoner informed Kenton that there were settlements to the south in Kentucky. Kenton and Williams visited these and decided to relocate.

In 1777 the Shawnee launched three attacks against Boonesborough, the settlement founded by Daniel Boone where Kenton was then living. During the first attack, Boone and thirteen others including Kenton were caught outside the fort with the Shawnee between them and the gate. During the ensuring fight, Boone was shot in the leg, the bullet breaking his bone and forcing him to collapse onto the ground. A Shawnee warrior raised his tomahawk to end Boone’s life, but it never struck home: Kenton shot the fellow, earning Boone’s praise.

In 1778 Boone led an attack on a Shawnee village along Paint Creek. An unexpected skirmish with Shawnee warriors on the way there prompted Boone to return home because element of surprise had been lost. Kenton and another man, Alexander Montgomery, stayed behind to spy on the Paint Creek settlement. For two days they watched. Then came a chance to steal two horses, which they did, a success that gave them a taste for horse thievery.

Around September 1, 1778, Kenton, Alexander Montgomery, and the flaming red-haired George Clark (the older brother of William Clark, he of Lewis and Clark fame) headed out to spy on the Shawnee town of Chillicothe. The name meant “principal town,” a place that served as a seasonal capital. The town Kenton and Montgomery spied upon was located along the Little Miami River near Xenia, Ohio, and has no relationship to the modern Ohio town of Chillicothe.

"Kenton and the Renegade Girty"

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Frank Triplet (New York: N.D. Thompson Publishing Co., 1885).

Digitized by Google Books.

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Frank Triplet (New York: N.D. Thompson Publishing Co., 1885).

Digitized by Google Books.

"Kenton and Logan"

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Frank Triplet (New York: N.D. Thompson Publishing Co., 1885).

Digitized by Google Books.

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Frank Triplet (New York: N.D. Thompson Publishing Co., 1885).

Digitized by Google Books.

The three saw seven horses grazing in the open and decided to steal them. Each man mounted one and used it to round up the others. This proved a bit noisy and someone noticed, so the thieves headed toward the Ohio River at a place near modern Georgetown, Ohio, with the idea of crossing it to reach the safety of Louisville, Kentucky. Unfortunately for them, a near hurricane-force wind had so whipped up the river, making it impossible to get more than halfway across before being forced to turn back.

Instead of running for their lives to escape the pursuing Shawnee, they waited for the wind to die down. A second attempt to cross failed during which several horses escaped. Rather than cut their losses, the three split up to find the missing horses. Kenton had barely gone a hundred yards when he heard a whoop. He inexplicably dismounted and headed toward the source of the noise only to encounter three Shawnees and a white man on horses.

He raised his rifle and fired at the nearest man to warn his companions of their presence, but his powder was wet from his plunge into the river, so he got nothing more than a flash in his gun’s pan. Instead of trying to remount and gallop for his life, he ran on foot into a place with many fallen trees. One of the Shawnees came upon him and, dismounting, rushed Kenton with his tomahawk. As Kenton raised his rifle to block the oncoming blow, another Shawnee snuck upon Kenton from behind and grabbed him by the arms.

The Shawnees stuck two stakes into the ground, bound Kenton’s feet to them, then tied his upper body to a tree. As they did this, Montgomery came upon the scene. He fired at the Shawnee, missed, then took off running. The Shawnee pursued. Kenton heard a shot in the distance, and shortly thereafter Montgomery’s pursuers returned with his bloody scalp and shook it in front of Kenton’s face. They repeatedly struck him with ramrods and called him a thief.

The next morning they placed him on a wild colt with no saddle or bridle. A rope was slung underneath the beast to secure Kenton’s feet, another bound his arms, and a third went around his neck on one end, and the horse’s neck on the other. The horse was enticed to gallop through the thick woods. Unable to move or protect himself, the brush repeatedly slapped and cut Kenton. After the horse had calmed down, the Shawnee asked him if he wanted to steal horses now.

Instead of running for their lives to escape the pursuing Shawnee, they waited for the wind to die down. A second attempt to cross failed during which several horses escaped. Rather than cut their losses, the three split up to find the missing horses. Kenton had barely gone a hundred yards when he heard a whoop. He inexplicably dismounted and headed toward the source of the noise only to encounter three Shawnees and a white man on horses.

He raised his rifle and fired at the nearest man to warn his companions of their presence, but his powder was wet from his plunge into the river, so he got nothing more than a flash in his gun’s pan. Instead of trying to remount and gallop for his life, he ran on foot into a place with many fallen trees. One of the Shawnees came upon him and, dismounting, rushed Kenton with his tomahawk. As Kenton raised his rifle to block the oncoming blow, another Shawnee snuck upon Kenton from behind and grabbed him by the arms.

The Shawnees stuck two stakes into the ground, bound Kenton’s feet to them, then tied his upper body to a tree. As they did this, Montgomery came upon the scene. He fired at the Shawnee, missed, then took off running. The Shawnee pursued. Kenton heard a shot in the distance, and shortly thereafter Montgomery’s pursuers returned with his bloody scalp and shook it in front of Kenton’s face. They repeatedly struck him with ramrods and called him a thief.

The next morning they placed him on a wild colt with no saddle or bridle. A rope was slung underneath the beast to secure Kenton’s feet, another bound his arms, and a third went around his neck on one end, and the horse’s neck on the other. The horse was enticed to gallop through the thick woods. Unable to move or protect himself, the brush repeatedly slapped and cut Kenton. After the horse had calmed down, the Shawnee asked him if he wanted to steal horses now.

"A Western Mazeppa—Simon Kenton a Prisoner"

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Augustus Lynch Mason and John Clark Ridpath (New York: N.D. Thompson Publishing Co., 1885).

Digitized by Google Books.

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Augustus Lynch Mason and John Clark Ridpath (New York: N.D. Thompson Publishing Co., 1885).

Digitized by Google Books.

They took and their prisoner to Chillicothe, a three day journey during which Kenton was tied up spread-eagled each night to maximize his discomfort. Before entering Chillicothe proper, Chief Blackfish, the Shawnee war leader who had once adopted Daniel Boone, came to see Kenton. He asked the prisoner if he’d been stealing Shawnee horses. He had. Had Daniel Boone sent him? No. Blackfish said nothing more, preferring to spend his energy bloodying Kenton’s shoulders and back with a hickory switch.

Kenton was stripped naked and tied to a pole. About 150 people from the nearby town danced around him, whooping and striking him with switches or the palms of their hands. This they did for about three hours. Around midnight he was taken into Chillicothe.

While not all Native Americans practiced torture, it was unfortunate for Kenton that the warlike Shawnee did. The next morning they had another form of it for him. Two long lines of Shawnees about six feet apart formed. In their hands were switches, clubs, hoe handles, tomahawks, and other instruments designed to cause maximum pain as Kenton ran this gauntlet. A drum beat as his made his way through. Seeing two Shawnees with butcher knives, Kenton rammed through the line and ran east with the hope that it was true that if a man going through the gauntlet reached town, his ordeal was over.

Kenton was stripped naked and tied to a pole. About 150 people from the nearby town danced around him, whooping and striking him with switches or the palms of their hands. This they did for about three hours. Around midnight he was taken into Chillicothe.

While not all Native Americans practiced torture, it was unfortunate for Kenton that the warlike Shawnee did. The next morning they had another form of it for him. Two long lines of Shawnees about six feet apart formed. In their hands were switches, clubs, hoe handles, tomahawks, and other instruments designed to cause maximum pain as Kenton ran this gauntlet. A drum beat as his made his way through. Seeing two Shawnees with butcher knives, Kenton rammed through the line and ran east with the hope that it was true that if a man going through the gauntlet reached town, his ordeal was over.

Two or three hundred Shawnee pursued him. At the outskirts of town, a Shawnee there carrying a blanket threw it around Kenton and forced him onto the ground. So worn and damaged was he from the previous tortures he’d suffered, he lacked the strength to resist. Rather than force him back into the gauntlet, the Shawnee gave him some food and water and took him to the council house, the point at which this article began.

Deciding to make his death a public spectacle, the place of execution was named as Wapatomika, modern day Zanesfield (not to be confused with Zanesville, another Ohio town entirely). As they headed to this destination, they passed through the Shawnee town of Pickaway, located near modern Springfield, where another council formed. It, too, saw fit to condemn Kenton to death. Next he came to Machecheek where he was beaten badly and left alone for a time. Seeing no guards, he ran for it. Though pursued, he soon lost those who chased him. About two miles away he came upon Shawnees on horseback who easily ran him down and returned him to town. As punishment, a group of young Shawnees took him to a creek where they dragged him through mud and water, nearly suffocating him.

In Wapatomika he ran the gauntlet once more, an experience that left him seriously hurt. Then came still another council to decide on his fate, which was a foregone conclusion. Before this meeting started, he was painted completely black. British agents Simon Girty, his brother James, and John Ward showed up along with several captives that included Mrs. Mary Kennedy and seven children, though they were taken away shortly after appearing.

Girty, who spoke Algonquin fluently and served as translator, failed to recognize Kenton because he’d been painted black. Likely, too, his face was swollen from the many tortures he’d received. Girty placed a blanket on the ground and commanded Kenton to sit on ii. When he failed to respond, Girty grabbed him by the arms and forced him to do so. He asked Kenton where he lived. Kentucky. How many men were in Kentucky? He didn’t know but did give then name of honorary officers who commanded no men. What was his name? Simon Butler, “Butler” being the last name he used because he still thought he was wanted for murder.

Suddenly Girty went from harsh interrogator to distressed friend. He hugged Kenton and began weeping, “calling him [according to the account written by John McDonald] his dear and esteemed friend.” Girty determined to save Kenton’s life and launched into a speech to the council in which he pointed out that he’d never spoken on behalf of an American before and never would again, but in this case he asked them to spare Kenton’s life. He reminded the Shawnee that he he’d never once requested anything in return for his service to the them.

American historians, especially those writing in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, almost always labeled Girty a “renegade,” a word here with racist implications. To their minds it was unconscionable that a white man would fight like a Native American and live among them. Never mind that many other Americans considered “heroes” did the same thing. The fact that Girty fought for the British during the American Revolution after seeming to have first chosen the Patriot side further blackened his name. Yet his relationship with Native Americans was nuanced, nor was he a traitor to the American cause because he’d never joined it in the first place.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1741, his father and stepfather were both killed by Native Americans. He fought in the French and Indian War and was taken prisoner by the Seneca for thirty-six months during which time he learned their language and ways. Upon his release in 1759, he became an interpreter for the British at Fort Pitt. Although he lived with native tribes at times, he didn’t hesitate to fight on the side of the colonists during Lord Dunmore’s War.

When the American Revolution broke out, he claimed to side with the Patriots but probably did so to subvert the cause. His time with them was in any case short-lived. In late 1777 the Mingo, Delaware and Shawnee formally allied themselves with the British, prompting the Continental Army’s commander at Fort Pitt to order the arrest of Girty and other suspected Tories. Upon hearing this, Girty and his associates made their way to Detroit and there formally came under the command of the British lieutenant governor, Henry Hamilton. Like many Loyalists, Girty settled in Canada after the war.

The Shawnee agreed to spare Kenton’s life and gave him over to Girty. He took Kenton to his wigwam and supplied him with items from his own stores. For about twenty days the two traveled freely from Shawnee town to town, giving Kenton’s many wounds time to heal.

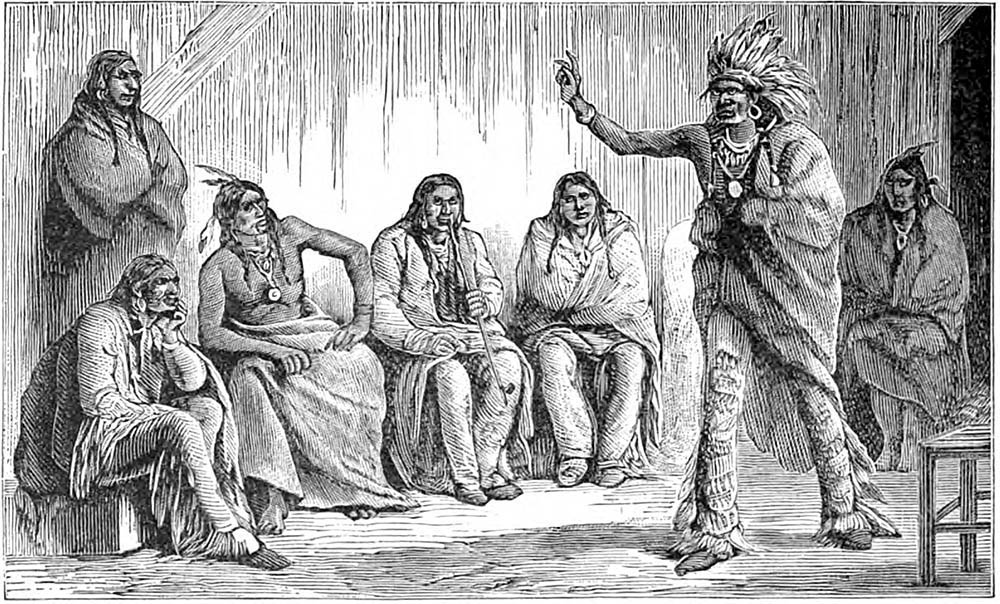

During this reprieve, a Shawnee war party launched an attack at a place near modern Wheeling, West Virginia, and there was soundly defeated. Returning home, its members decided to take their frustration at this failure out on the only colonist available to them. Girty and Kenton were at that latter’s home in a place called Solomon’s Town when a messenger named Redpole arrived to tell them they’d been summoned by the council at Wapatomika. Tellingly, Redpole shook Girty’s hand but refused Kenton’s.

The council reinstated the sentence of death upon Kenton. When Girty’s plea to rescind this decision was ignored, he tried another tact. At this time the British had an outpost at Lower Sandusky (modern Fremont, Ohio) at which they paid their Native American allies annuities. The British would surely give them a good reward for bringing them Kenton. Greed trumped revenge and the council agreed to take Kenton there.

Deciding to make his death a public spectacle, the place of execution was named as Wapatomika, modern day Zanesfield (not to be confused with Zanesville, another Ohio town entirely). As they headed to this destination, they passed through the Shawnee town of Pickaway, located near modern Springfield, where another council formed. It, too, saw fit to condemn Kenton to death. Next he came to Machecheek where he was beaten badly and left alone for a time. Seeing no guards, he ran for it. Though pursued, he soon lost those who chased him. About two miles away he came upon Shawnees on horseback who easily ran him down and returned him to town. As punishment, a group of young Shawnees took him to a creek where they dragged him through mud and water, nearly suffocating him.

In Wapatomika he ran the gauntlet once more, an experience that left him seriously hurt. Then came still another council to decide on his fate, which was a foregone conclusion. Before this meeting started, he was painted completely black. British agents Simon Girty, his brother James, and John Ward showed up along with several captives that included Mrs. Mary Kennedy and seven children, though they were taken away shortly after appearing.

Girty, who spoke Algonquin fluently and served as translator, failed to recognize Kenton because he’d been painted black. Likely, too, his face was swollen from the many tortures he’d received. Girty placed a blanket on the ground and commanded Kenton to sit on ii. When he failed to respond, Girty grabbed him by the arms and forced him to do so. He asked Kenton where he lived. Kentucky. How many men were in Kentucky? He didn’t know but did give then name of honorary officers who commanded no men. What was his name? Simon Butler, “Butler” being the last name he used because he still thought he was wanted for murder.

Suddenly Girty went from harsh interrogator to distressed friend. He hugged Kenton and began weeping, “calling him [according to the account written by John McDonald] his dear and esteemed friend.” Girty determined to save Kenton’s life and launched into a speech to the council in which he pointed out that he’d never spoken on behalf of an American before and never would again, but in this case he asked them to spare Kenton’s life. He reminded the Shawnee that he he’d never once requested anything in return for his service to the them.

American historians, especially those writing in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, almost always labeled Girty a “renegade,” a word here with racist implications. To their minds it was unconscionable that a white man would fight like a Native American and live among them. Never mind that many other Americans considered “heroes” did the same thing. The fact that Girty fought for the British during the American Revolution after seeming to have first chosen the Patriot side further blackened his name. Yet his relationship with Native Americans was nuanced, nor was he a traitor to the American cause because he’d never joined it in the first place.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1741, his father and stepfather were both killed by Native Americans. He fought in the French and Indian War and was taken prisoner by the Seneca for thirty-six months during which time he learned their language and ways. Upon his release in 1759, he became an interpreter for the British at Fort Pitt. Although he lived with native tribes at times, he didn’t hesitate to fight on the side of the colonists during Lord Dunmore’s War.

When the American Revolution broke out, he claimed to side with the Patriots but probably did so to subvert the cause. His time with them was in any case short-lived. In late 1777 the Mingo, Delaware and Shawnee formally allied themselves with the British, prompting the Continental Army’s commander at Fort Pitt to order the arrest of Girty and other suspected Tories. Upon hearing this, Girty and his associates made their way to Detroit and there formally came under the command of the British lieutenant governor, Henry Hamilton. Like many Loyalists, Girty settled in Canada after the war.

The Shawnee agreed to spare Kenton’s life and gave him over to Girty. He took Kenton to his wigwam and supplied him with items from his own stores. For about twenty days the two traveled freely from Shawnee town to town, giving Kenton’s many wounds time to heal.

During this reprieve, a Shawnee war party launched an attack at a place near modern Wheeling, West Virginia, and there was soundly defeated. Returning home, its members decided to take their frustration at this failure out on the only colonist available to them. Girty and Kenton were at that latter’s home in a place called Solomon’s Town when a messenger named Redpole arrived to tell them they’d been summoned by the council at Wapatomika. Tellingly, Redpole shook Girty’s hand but refused Kenton’s.

The council reinstated the sentence of death upon Kenton. When Girty’s plea to rescind this decision was ignored, he tried another tact. At this time the British had an outpost at Lower Sandusky (modern Fremont, Ohio) at which they paid their Native American allies annuities. The British would surely give them a good reward for bringing them Kenton. Greed trumped revenge and the council agreed to take Kenton there.

"The Warrior's Party to Girty, Demanding Kenton's Death"

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Augustus Lynch Mason and John Clark Ridpath (New York: N.D. Thompson Publishing Co., 1885).

Digitized by Google Books.

Taken from Conquering the Wilderness; or a New Pictorial History & Life and Times of Pioneer Heroes and Heroines of America by Augustus Lynch Mason and John Clark Ridpath (New York: N.D. Thompson Publishing Co., 1885).

Digitized by Google Books.

Upon seeing the American, the man grabbed the axe his wife was using to chop wood, leapt at Kenton, and struck him with it in the shoulder, cutting deep and breaking a bone. His guards prevented this attacker from doing any more damage because they wanted their prize whole.

While traveling along the Scioto River, they came across James Logan, who had returned to fighting the Americans now that the British backed this cause. Despite his hatred of the whites, for reasons never made clear in the primary sources about this encounter, Logan took pity upon Kenton and determined that his death sentence should be revoked. To that end he sent two runners ahead to Lower Sandusky to speak on Kenton’s behalf, though after their return the fact that Logan spoke no more to Kenton caused him to conclude it had failed.

At Lower Sandusky Kenton had to attend still another Shawnee council. (One can’t accuse the Shawnee of not considering things carefully nor of being undemocratic since these meetings involved a vote of consensus.) A French-Canadian British captain and Indian agent named Pierre Druillard spoke to the council and told it that the British would be very grateful indeed if Kenton were released to him so he could be interrogated by the commanding general there. In return Druillard would personally give them one hundred dollars’ worth of tobacco, rum, or anything else they desired. And, of course, he’d return the prisoner to them at a later date so they could burn him at the stake. This offer was too good to be refused. Kenton was released into British custody. Probably Druillard had acted at the behest of his good friend James Logan. Certainly he had no intention of giving Kenton back to the Shawnee.

A boat took Kenton up the Sandusky River to Lake Erie and across that to Detroit. He arrived at the beginning of November. The British questioned him extensively but he gave nothing important away. Satisfied he had no more information, they granted him the run of Detroit, though he was forbidden to leave town. The latter prohibition was a mere formality. They well knew if he left, the Shawnee might get hold of and execute him.

Kenton’s shoulder wound healed up. He did some work for half-rations and found life quite pleasant. He wanted his freedom but saw no ready way to made his escape. Then American prisoners from Kentucky arrived in early Spring of 1779 that included two of his former comrades, Jesse Coffer and Captain Nathan Bullit. They, too, were given their liberty so long as they stayed in Detroit. The three discussed escape. The obstacles were daunting. To reach the safety of Kentucky they had to cross over 400 miles of wilderness filled with hostile Native Americans. This was in addition to many natural hazards such as cold and floods.

At twenty-three years of age, Kenton was quite the lady’s man, and he aimed his charm at Mrs. Harvey, the wife of an Indian trader. He thought she might be willing to help him and his compatriots to escape, though he well knew she might just as easily report him to the authorities, which would result in confinement. During a private moment he asked her for help. She said she had no money to give him. He replied that he and his friends possessed that. What they needed was for her to purchase the supplies they required for a journey across the wilderness. If they bought them, it would raise suspicions.

Agreeing, she acquired items such as moccasins, lead for bullets, and dried beef that she hid in a hollow tree outside of town. A gun would also be necessary, but a woman buying one would bring unwanted attention. Mrs. Harvey offered to give them her husband’s fowling piece if another one couldn’t be found, but an opportunity arose that made this a moot proposition. On June 3, 1779, a party of armed Native Americans came to town to party. They left their guns with Mrs. Harvey, so she chose the best three and hid them in her garden among the peas.

She left a ladder outside the garden, which was surrounded by a fence, so Kenton could acquire the them that night. Thus armed, Kenton and his two companions went to the hollow tree to get their supplies. They headed southwest at the suggestion of a Scottish Indian trader named McKinzie who had told Kenton on the sly that the best way to avoid Native Americans was to make for the Wabash River and follow it south into Kentucky.

They traveled mostly at night. Running out of food by the time they reached the Wabash, they went for days without eating because the prairie lacked any game. One day as they emerged from a thicket, they saw a Native American village, prompting them to dart back where they came from and hide. So hungry were they, Coffer and Bullit suggested surrendering in the hope they’d be well treated. Kenton dissuaded them of this idea.

That night they snuck around the village and by morning entered a woods in which they immediately saw a buck. Kenton shot it. Being far enough from the village to do so safely, they made a fire and cooked it up. Three days later they reached the safety of Louisville. Their trek had taken thirty days.🕜

While traveling along the Scioto River, they came across James Logan, who had returned to fighting the Americans now that the British backed this cause. Despite his hatred of the whites, for reasons never made clear in the primary sources about this encounter, Logan took pity upon Kenton and determined that his death sentence should be revoked. To that end he sent two runners ahead to Lower Sandusky to speak on Kenton’s behalf, though after their return the fact that Logan spoke no more to Kenton caused him to conclude it had failed.

At Lower Sandusky Kenton had to attend still another Shawnee council. (One can’t accuse the Shawnee of not considering things carefully nor of being undemocratic since these meetings involved a vote of consensus.) A French-Canadian British captain and Indian agent named Pierre Druillard spoke to the council and told it that the British would be very grateful indeed if Kenton were released to him so he could be interrogated by the commanding general there. In return Druillard would personally give them one hundred dollars’ worth of tobacco, rum, or anything else they desired. And, of course, he’d return the prisoner to them at a later date so they could burn him at the stake. This offer was too good to be refused. Kenton was released into British custody. Probably Druillard had acted at the behest of his good friend James Logan. Certainly he had no intention of giving Kenton back to the Shawnee.

A boat took Kenton up the Sandusky River to Lake Erie and across that to Detroit. He arrived at the beginning of November. The British questioned him extensively but he gave nothing important away. Satisfied he had no more information, they granted him the run of Detroit, though he was forbidden to leave town. The latter prohibition was a mere formality. They well knew if he left, the Shawnee might get hold of and execute him.

Kenton’s shoulder wound healed up. He did some work for half-rations and found life quite pleasant. He wanted his freedom but saw no ready way to made his escape. Then American prisoners from Kentucky arrived in early Spring of 1779 that included two of his former comrades, Jesse Coffer and Captain Nathan Bullit. They, too, were given their liberty so long as they stayed in Detroit. The three discussed escape. The obstacles were daunting. To reach the safety of Kentucky they had to cross over 400 miles of wilderness filled with hostile Native Americans. This was in addition to many natural hazards such as cold and floods.

At twenty-three years of age, Kenton was quite the lady’s man, and he aimed his charm at Mrs. Harvey, the wife of an Indian trader. He thought she might be willing to help him and his compatriots to escape, though he well knew she might just as easily report him to the authorities, which would result in confinement. During a private moment he asked her for help. She said she had no money to give him. He replied that he and his friends possessed that. What they needed was for her to purchase the supplies they required for a journey across the wilderness. If they bought them, it would raise suspicions.

Agreeing, she acquired items such as moccasins, lead for bullets, and dried beef that she hid in a hollow tree outside of town. A gun would also be necessary, but a woman buying one would bring unwanted attention. Mrs. Harvey offered to give them her husband’s fowling piece if another one couldn’t be found, but an opportunity arose that made this a moot proposition. On June 3, 1779, a party of armed Native Americans came to town to party. They left their guns with Mrs. Harvey, so she chose the best three and hid them in her garden among the peas.

She left a ladder outside the garden, which was surrounded by a fence, so Kenton could acquire the them that night. Thus armed, Kenton and his two companions went to the hollow tree to get their supplies. They headed southwest at the suggestion of a Scottish Indian trader named McKinzie who had told Kenton on the sly that the best way to avoid Native Americans was to make for the Wabash River and follow it south into Kentucky.

They traveled mostly at night. Running out of food by the time they reached the Wabash, they went for days without eating because the prairie lacked any game. One day as they emerged from a thicket, they saw a Native American village, prompting them to dart back where they came from and hide. So hungry were they, Coffer and Bullit suggested surrendering in the hope they’d be well treated. Kenton dissuaded them of this idea.

That night they snuck around the village and by morning entered a woods in which they immediately saw a buck. Kenton shot it. Being far enough from the village to do so safely, they made a fire and cooked it up. Three days later they reached the safety of Louisville. Their trek had taken thirty days.🕜

Daniel Boone

1876. Library of Congress.

1876. Library of Congress.