The Smithsonian

Incan Bridge

Inside the National Museum

of the American Indian

of the American Indian

Incan Figurine

Incan Idol

Incan Bowl

National Museum of the American Indian

So far as I’m concerned, the best museum in America is the Smithsonian. Except it isn’t really a museum but rather a series of them, each dedicated to a given subject. And while most of these stand along the Mall in Washington, D.C., a few are scattered elsewhere, including the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, and the National Museum of the American Indian’s George Gustav Heye Center in New York City. Having visited the Smithsonian on the Mall sometime in the early 2000s—probably in 2004 or 2005—I’d always planned to return. On my agenda for this trip were the National Museum of American History, the National Museum of the American Indian, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture. As it turned out, I couldn’t obtain tickets for the last, which is just as well considering the vast amount of time I spent in the other two.

Unlike the other Smithsonian attractions, there wasn’t a line to get in National Museum of the American Indian due to a lack of interest. This is unfortunate because here visitors can learn about Native American culture, see art both past and modern, and immerse themselves in a part of U.S. history schoolbooks would do well to look at in much greater detail. The museum building—an architectural wonder—rises four floors, though only the third and fourth have exhibits. The first contains a few displays plus a small gift shop and a café that serves Native American foods, and the second has nothing but a much larger gift shop.

Exhibits are well designed and include numerous activities for children, always a good idea because they do have a tendency to get bored easily. One of my favorite galleries was The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire. Another one I especially liked was Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations that focuses on the mistreatment and forced removal of Native Americans to the west. One especially appalling idea the U.S. government once implemented was the hideous termination program that removed tribes from their reservations, confiscated their land, relocated them to urban centers, and withdrew their people’s special status. Fortunately resistance and public opinion put a stop to this. I think we owe the Native Americans much to this day, though what compensation we offer is never going to undo the damage done in terms in the loss of life as well as culture, history and language. I also believe the United States committed outright genocide against them. This idea is briefly mentioned, but there ought to be an entire exhibit dedicated to the subject.

National Museum of American History

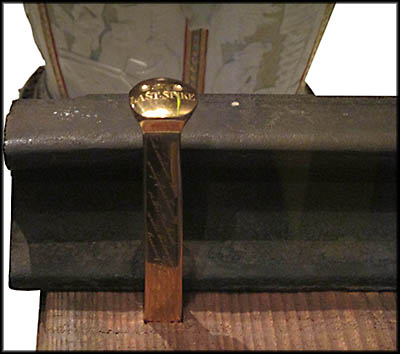

Other historic objects that caught my attention include Benjamin Franklin’s walking stick, the golden railroad spike used to connect the Union and Central Pacific Railroads that ushered in America’s first transcontinental railway, and two beams from the South Twin Tower brought down in the attacks of September 11, 2001. Surely the most precious object the museum possesses is the Great Garrison Flag that the flew over Fort McHenry during the British attack upon it in 1814. Its refusal to surrender inspired one witness, Francis Scott Key, to write the poem “Star-Spangled Banner.” When last I saw this huge flag (it is 30 by 42 feet), it was in sad shape. A sign noted it was due for restoration. And restore it the museum did. It now resides in a darkened gallery in all its glory where photography is forbidden.

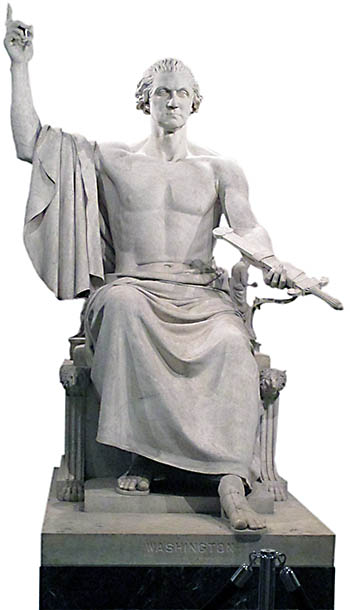

A somewhat unsettling statue George Washington by Horatio Greenough.

I spent five hours in the American History museum, and even then I rushed through several galleries. Some of my favorite exhibits include America on the Move, American Enterprise, and American Stories. The museum is loaded with artifacts from U.S. history, some more obscure than others. Take the George Washington Statue. It is a somewhat bizarre marble figure of George Washington portrayed as a half-naked Greek god with a perfect muscular body the real man never had. In 1832, Congress commissioned Horatio Greenough to sculpt this twelve-ton monstrosity for display in the Capitol rotunda. Unveiled in 1841, it received mixed reactions from the public. Some liked the symbolism of a god-like Washington while others were upset by its upper-body nudity. Clearly the latter opinion won out, because now you find it by the elevators on the second floor of the American History museum and not somewhere in the Capitol.

During my trip to Washington, D.C., I visited places beyond the Smithsonian. One of these was the Library of Congress, which is not a single building but rather three connected underground so once you pass through security you can move among them unhindered. The British burned down the original Library, and fires took their toll on its replacement. In 1886 Congress authorized the construction of a new building to hold its ever-increasing collection. Designed to look as if it came from the Renaissance, it opened in 1897 and is now known as the Thomas Jefferson Building. Here one can take a free guided tour, most of which you can’t hear due to the noise from the massive crowds wandering about.

This is an original can of Pringle's. It is significant because it says, "Potato Chips," not "Potato Crisps" as you see today. This is because of a lawsuit by traditional potato chip companies who cried foul that these perfectly-shaped munchies weren't real potato chips.

Near the Smithsonian is Ford’s Theater, the place in which Lincoln was assassinated, requires you acquire tickets ahead of time that dictate what time you can visit. The tickets are free, though you do pay a nominal transaction fee if you acquire them online. The theater has a small but informative museum in its basement and, depending on when you go, a Park Ranger gives a presentation in the theater proper. Unless you feel you absolutely must visit, I recommend avoiding it because overcrowding makes getting around more difficult than it is worth.🕜

Incan Jug and Cup

Trolley

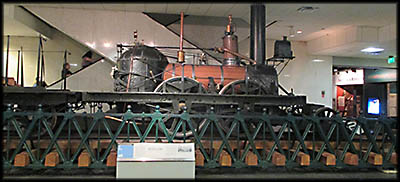

This is the John Bull locomotive, the oldest locomotive in America that can still run. It last did so in 1981.

This is the kitchen studio used by Julia Child for her television show.

Slurpee Cups from the 1970s

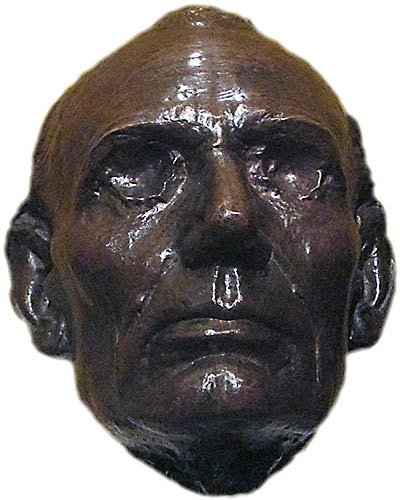

Lincoln death mask made in 1860 by Leonard W. Volk.

Library of Congress (Jefferson Building)

Ford's Theater

The golden spike used to unite the tracks of the Union and Central Pacific Railroads on May 10, 1869.