Thurmond and Nuttallburg, WV

Thurmond

This is the bridge we had to drive over to get to Thurmond. I took this photo after we crossed.

Thurmond Depot

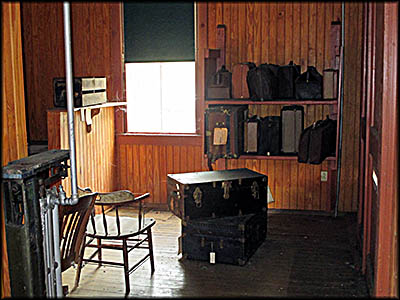

Baggage Area of the Thurmond Depot

Inside the Thurmond Depot

My visit to the West Virginian ghost towns of Thurmond and Nuttallburg was quite unexpected. It began with a phone call from my brother. He asked if I’d like to go whitewater rafting. This being something I’d always wanted to try, I readily agreed. Within a week I paid money to a company called Adventures on the Gorge that hosts whitewater raft trips on the New River as well as the upper and lower parts of the Gauley River. The New River, the easiest of the routes and the one my brother and I ultimately took, cuts through a deep gorge known as the New River Gorge over which is a bridge that is the third highest in the United States that I went over in a car and under in raft.

During the trip my brother and I shared a cabin with four others who were members of his ski club, two of whom I had met just a few days earlier and one at our destination. At the cabin four of us, myself included, stuffed ourselves into a small upstairs bedroom. The next morning I was informed that I had snored so loudly and consistently that one of my roommates fled to his RV to sleep while another went downstairs to escape the noise. It didn’t seem to matter at the time, because I was a bit anxious about going whitewater rafting, plus my brother and I would have the cabin to ourselves that night because the other four were doing an overnight trip at the Gauley River. The rafting turned out to be pretty boring over all because although running the rapids is exhilarating, the journey to get from one to the other is not.

During the trip my brother and I shared a cabin with four others who were members of his ski club, two of whom I had met just a few days earlier and one at our destination. At the cabin four of us, myself included, stuffed ourselves into a small upstairs bedroom. The next morning I was informed that I had snored so loudly and consistently that one of my roommates fled to his RV to sleep while another went downstairs to escape the noise. It didn’t seem to matter at the time, because I was a bit anxious about going whitewater rafting, plus my brother and I would have the cabin to ourselves that night because the other four were doing an overnight trip at the Gauley River. The rafting turned out to be pretty boring over all because although running the rapids is exhilarating, the journey to get from one to the other is not.

The next day my brother and I headed to Thurmond with the plan to visit Nuttallburg afterward. Traveling in an automobile in West Virginia is a peculiar experience. As we followed a truck down a backroad, it suddenly pulled off, let us pass, then began following us. A few miles later we stopped dead when we reached a bridge beside which was a large sign informing us that it was out due to construction. As my brother pulled over and prepared to turn around, the truck zipped right pass us, shooting over the bridge without hesitation. Well, if it was good enough for a local vehicle, it was good enough for us, so over we went.

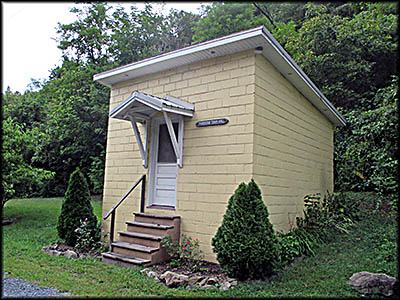

A few more miles and we stopped at a one-lane bridge that crossed the New River into Thurmond. After a brief discussion as to whether or not it was for pedestrians or vehicles, we decided to drive over it. Considering that I am writing these words, it clearly did not collapse. On the other side we parked at the Thurmond Depot, which is run as a museum by the National Park Service (NPS), which also caretakes some of Thurmond’s buildings. Despite the NPS’s control, the town is still governed by its five to seven residents from what must be one of America’s smallest townhalls, a photo of which can be found alongside this article.

A few more miles and we stopped at a one-lane bridge that crossed the New River into Thurmond. After a brief discussion as to whether or not it was for pedestrians or vehicles, we decided to drive over it. Considering that I am writing these words, it clearly did not collapse. On the other side we parked at the Thurmond Depot, which is run as a museum by the National Park Service (NPS), which also caretakes some of Thurmond’s buildings. Despite the NPS’s control, the town is still governed by its five to seven residents from what must be one of America’s smallest townhalls, a photo of which can be found alongside this article.

Thurmond traces its origins to the purchase of a large swatch of land in the New River Gorge by Morris Harvey after the Civil War. In 1873 he hired amateur surveyor Captain William Dabney Thurmond to map it. Unable to pay in hard cash, he instead gave Thurmond seventy-three acres, land that happened to be where the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad would put its mainline, which was on the northern bank of the New River. Thurmond started the town named after him where the Dun Loup Creek empties into the river.

It is because of the C&O that the town boomed like it did. By 1910, over 40% of its population worked for the C&O. While the majority of its profits came from hauling freight—there were sixty-seven coal mines in the New River Gorge and this was the only railroad to get it out—it also served as the biggest means of traveling through the region, with some fourteen to twenty passenger trains (statistics vary) going through during its heyday. In 1910 the town generated the C&O’s highest revenue.

It is because of the C&O that the town boomed like it did. By 1910, over 40% of its population worked for the C&O. While the majority of its profits came from hauling freight—there were sixty-seven coal mines in the New River Gorge and this was the only railroad to get it out—it also served as the biggest means of traveling through the region, with some fourteen to twenty passenger trains (statistics vary) going through during its heyday. In 1910 the town generated the C&O’s highest revenue.

Another big industry in Thurmond was the C&O yard at which its steam engines were repaired. Its trains also stopped in town to refuel, replenish water, and fill up with sand, this last being sprinkled onto slick tracks during foul weather. The C&O’s depot, built in 1904 after the original burned down, had two purposes: serve passengers and run the trains. The lower level was dedicated to the former. It contained, among other things, the baggage and waiting areas, restrooms, and the ticket office. The upper floor served home to the train master’s, conductors’, and dispatch offices as well as the signal tower.

One of the more interesting exhibits at the depot is about the symbols hobos riding freight trains left one another as messages. A triangle with two stick figure hands protruding from its angled sides reported that there was a man with a gun. An arch with a solid black dot meant authorities were on the alert. A stick figure cat represented a kind lady. A cross meant there was a religious talk with a free meal.

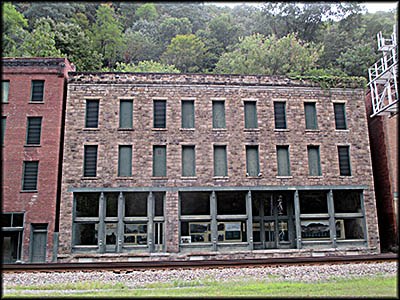

Because of the massive number of people who passed through or stopped at it, Thurmond had an outsized number of businesses one would not normally expect to find in such small town, which never had more than 500 permanent residents. There were, for example, two general stores, a restaurant (Mrs. McClure’s), a jeweler, and an office for the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency. Another industry in town was the Armour Meat Packing Company, which closed in 1937, its abandoned factory burning down in 1963. The town never had a proper main street. The closest it came was the strip of road between the tracks and the front of its main buildings.

One of the more interesting exhibits at the depot is about the symbols hobos riding freight trains left one another as messages. A triangle with two stick figure hands protruding from its angled sides reported that there was a man with a gun. An arch with a solid black dot meant authorities were on the alert. A stick figure cat represented a kind lady. A cross meant there was a religious talk with a free meal.

Because of the massive number of people who passed through or stopped at it, Thurmond had an outsized number of businesses one would not normally expect to find in such small town, which never had more than 500 permanent residents. There were, for example, two general stores, a restaurant (Mrs. McClure’s), a jeweler, and an office for the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency. Another industry in town was the Armour Meat Packing Company, which closed in 1937, its abandoned factory burning down in 1963. The town never had a proper main street. The closest it came was the strip of road between the tracks and the front of its main buildings.

Two hotels served Thurmond. One, the Thurmond (later called Lafayette) was a brick structure that contained, according to an information sign, “seven bathrooms, steam heat and 400 electric lights.” It burned down in 1963. A more impressive hotel was the three story Dunglen just up the New River. Built in 1901, it had 100 rooms and was the place where the coal barons who had come to see their mines stayed. It became infamous for its debauched gatherings, alcohol (which was banned in Thurmond itself), and gambling. It burned down on June 22, 1930.

It didn’t escape my notice that an awful lot of the town’s buildings had burned down, so I asked the park ranger at the depot museum about this. He said they had all burned because of arson, then expanded on that answer. It turns out that in West Virginia, or at least this part of it, when a person wants revenge, he or she has that person’s house or business burned down. The perpetrator is almost never caught because no one will talk. Even more astonishing, a friend of this ranger’s had had his house destroyed by an arsonist just months before. Apparently this is still happening!

What the C&O gave Thurmond it also took away. In the mid-1950s it switched to diesel engines, which were much cheaper to operate and maintain than their steam counterparts. Now trains no longer had to stop for refueling, nor was the repair shop needed. Even worse for the town’s economy, many of the New River Gorge’s coal mines had by now shut down, significantly reducing the amount of freight the C&O had to transport from here.

It didn’t escape my notice that an awful lot of the town’s buildings had burned down, so I asked the park ranger at the depot museum about this. He said they had all burned because of arson, then expanded on that answer. It turns out that in West Virginia, or at least this part of it, when a person wants revenge, he or she has that person’s house or business burned down. The perpetrator is almost never caught because no one will talk. Even more astonishing, a friend of this ranger’s had had his house destroyed by an arsonist just months before. Apparently this is still happening!

What the C&O gave Thurmond it also took away. In the mid-1950s it switched to diesel engines, which were much cheaper to operate and maintain than their steam counterparts. Now trains no longer had to stop for refueling, nor was the repair shop needed. Even worse for the town’s economy, many of the New River Gorge’s coal mines had by now shut down, significantly reducing the amount of freight the C&O had to transport from here.

Nuttallburg, which like Thurmond is in the New River Gorge, is about six and a half miles from Thurmond as the crow flies but an hour away for land-based vehicles. The latter takes so much longer because a vehicle has to traverse narrow, winding roads with cliff edges. West Virginia is, as anyone who has traveled through it knows, pretty mountainous, and these natural wonders have a bad habit of blocking phone signals and GPS satellite links. So if you depend on either device for finding your destination such as we did, getting lost is inevitable, and that’s exactly what happened. A one lane road we traversed, for example, simply gave out and turned into a deep rutted path that only the most ambitious off-road vehicle would dare tackle. With a sheer drop to the right and the side of the mountain to the left, my brother had no choice but to back up to road we had turned off of.

I found it interesting that the worse shape a house or trailer is in, the more likely it is to have a No Trespassing sign or something similar posted. If you own such a structure, let me tell you a little secret: when I see a place of residence with junk like an old refrigerator on the porch, shutters falling off the windows, and paint either peeling or missing, I will not be bothering you. In fact, you would have to pay me a large sum of money just to risk knocking on your front door. And I assure you that you are not on any burglar’s list. Arsonists, I will admit, are another matter.

When we finally did get on track to Nuttallburg, it was via a one-lane road that was mostly gravel interrupted by short paved sections. We had come here for two purposes: to hike and to see the coal tipple, the function of which I learned by reading the NPS information sign about it. Coal tipples were usually at the bottom of a mountain into which coal from the mine above was sent via a long conveyor. The tippled sorted coal by size, then either stored it, dropped it into train cars, or sent it to the nearby coke ovens. Nuttallburg’s tipple is, thanks to the NPS, in very good condition. It was built in 1923–1924 by the Fordson Coal Company, which was run by Edsel Ford and owned by his father, Henry of Ford Motor Company fame.

Nuttallburg was founded by John Nuttall, an immigrant born in England in 1817 who moved to the United States in 1849. Starting at the age of eleven, he worked in England’s coal mines for nearly twenty years. Upon arriving in America, he spent his first seven years working in a silk mill. With his savings and help from in-laws, he opened his first mine in Pennsylvania, then two more in the New River Gorge in 1873. In 1920 Fordson Coal leased it and other area coal mines in an effort to obtain the fuel needed to run Ford’s River Rouge factory. Frustrated by a lack of cooperation with the railroads, Henry gave up control of the mine in 1928, although it continued to operate until 1958.

I found it interesting that the worse shape a house or trailer is in, the more likely it is to have a No Trespassing sign or something similar posted. If you own such a structure, let me tell you a little secret: when I see a place of residence with junk like an old refrigerator on the porch, shutters falling off the windows, and paint either peeling or missing, I will not be bothering you. In fact, you would have to pay me a large sum of money just to risk knocking on your front door. And I assure you that you are not on any burglar’s list. Arsonists, I will admit, are another matter.

When we finally did get on track to Nuttallburg, it was via a one-lane road that was mostly gravel interrupted by short paved sections. We had come here for two purposes: to hike and to see the coal tipple, the function of which I learned by reading the NPS information sign about it. Coal tipples were usually at the bottom of a mountain into which coal from the mine above was sent via a long conveyor. The tippled sorted coal by size, then either stored it, dropped it into train cars, or sent it to the nearby coke ovens. Nuttallburg’s tipple is, thanks to the NPS, in very good condition. It was built in 1923–1924 by the Fordson Coal Company, which was run by Edsel Ford and owned by his father, Henry of Ford Motor Company fame.

Nuttallburg was founded by John Nuttall, an immigrant born in England in 1817 who moved to the United States in 1849. Starting at the age of eleven, he worked in England’s coal mines for nearly twenty years. Upon arriving in America, he spent his first seven years working in a silk mill. With his savings and help from in-laws, he opened his first mine in Pennsylvania, then two more in the New River Gorge in 1873. In 1920 Fordson Coal leased it and other area coal mines in an effort to obtain the fuel needed to run Ford’s River Rouge factory. Frustrated by a lack of cooperation with the railroads, Henry gave up control of the mine in 1928, although it continued to operate until 1958.

From the tipple you can hike half a mile up the mountain to see facility’s headhouse—the place from which the coal began its journey down the conveyor—but we had no desire to tackle this because it is really steep. Plus I had incorrectly thought it was a six mile journey. We did climb up the mountainside to see the remains of Nuttallburg itself as well as a nearby community known as Seldom Seen at which you will see nothing but a couple foundation blocks.

Not much is left of Nuttallburg, either. The crumbling remains of the coke ovens are still there, some of which you can go into. One of the first things John Nuttall did when he opened his mine was build these. These burned the impurities out of the coal, leaving behind the nearly pure carbon coke needed to make steel. I was told by one local person that when the coke ovens operated in the New River Gorge, everything was blackened by them. The ones here went idle around 1920, likely because new technologies to make coke made them obsolete.

Next to the ovens is the only structure we saw that still had some walls left: the company store. It is now overgrown with vegetation, as is everything else. The ruins of structures you can visit—and some we couldn’t see because of the overgrowth—are the White Church, White School (both of which are called this because of segregation, not their color), Small Home, Large House, Taylor House, and Large Home. For those who want to just sightsee, the coal tipple and coke ovens are the only thing worth looking at. It’s a steep climb to the other buildings and houses.

Getting to our cabin was not nearly as daunting as our journey to Nuttallburg since all we had to do was backtrack to the main road where our phones started to work once more. At the cabin we had a couple hours to ourselves before the others returned from their overnight trip. When they came back, they voted me out of the cabin and sent packing to the RV for the night so my snoring would not bother them.🕜

Not much is left of Nuttallburg, either. The crumbling remains of the coke ovens are still there, some of which you can go into. One of the first things John Nuttall did when he opened his mine was build these. These burned the impurities out of the coal, leaving behind the nearly pure carbon coke needed to make steel. I was told by one local person that when the coke ovens operated in the New River Gorge, everything was blackened by them. The ones here went idle around 1920, likely because new technologies to make coke made them obsolete.

Next to the ovens is the only structure we saw that still had some walls left: the company store. It is now overgrown with vegetation, as is everything else. The ruins of structures you can visit—and some we couldn’t see because of the overgrowth—are the White Church, White School (both of which are called this because of segregation, not their color), Small Home, Large House, Taylor House, and Large Home. For those who want to just sightsee, the coal tipple and coke ovens are the only thing worth looking at. It’s a steep climb to the other buildings and houses.

Getting to our cabin was not nearly as daunting as our journey to Nuttallburg since all we had to do was backtrack to the main road where our phones started to work once more. At the cabin we had a couple hours to ourselves before the others returned from their overnight trip. When they came back, they voted me out of the cabin and sent packing to the RV for the night so my snoring would not bother them.🕜

This is one of the most interesting and innovative exhibits I've ever seen (Thurmond Depot).

This is Thurmond's Town Hall.

Yard Master's Office (Thurmond Depot)

Thurmond Goodman-Kincaid Buiding

Coaling Tower (Thurmond)

Nuttallburg Tipple

The conveyor for the Nuttallburg Tipple goes up the mountainside. If you're feeling ambition, you can hike to the top.

Coke Ovens in Nuttallburg

Nuttallburg Company Store

This is all that remains of

Nuttalburg's church built for whites only.

Nuttalburg's church built for whites only.