Victorian House Museum

The Victorian House Museum is a large twenty-eight room house once built for Brightman family of Cleveland, which consisted of Latham H. Brightman, his wife, and eight children. Completed in 1901, the house was designed by Cleveland architect Fenimore C. Bate who is known for his Queen Anne-style architecture (whatever that is) and designing Cleveland’s Grays Armory. Brighton’s new house cost him $10,000 to build, which is about $300,000 today. Latham had this sort of cash because of the success of his business, the Brightman Machine Company in Cleveland. Two years after the family moved in, it left for Cleveland. Latham claimed this was because his business had gotten too big for him to run from Millersburg, but it seems more likely his family, used to big city life, got bored with a rural one and demanded to go back the city.

H.C. Griggs, a partner in the Lee & Griggs Construction Company, bought the house in 1907 for just $8,700. It stayed in the Griggs family until 1971 when the Holmes County Historical Society (HCHS) purchased it for a mere $12,500, hardly much more than what it cost to build way back in 1901. Probably this bargain was given because at the time the house wasn’t in great shape. Its very last occupant, Lena Lee, had little money and only lived in two of the house’s rooms that were covered in black soot produced by a coal stove. It took the HCHS three years to restore the home to its Victorian splendor.

H.C. Griggs, a partner in the Lee & Griggs Construction Company, bought the house in 1907 for just $8,700. It stayed in the Griggs family until 1971 when the Holmes County Historical Society (HCHS) purchased it for a mere $12,500, hardly much more than what it cost to build way back in 1901. Probably this bargain was given because at the time the house wasn’t in great shape. Its very last occupant, Lena Lee, had little money and only lived in two of the house’s rooms that were covered in black soot produced by a coal stove. It took the HCHS three years to restore the home to its Victorian splendor.

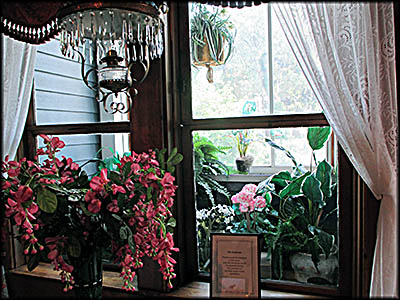

All hand-decorated ceilings have been restored by Winesburg artist, [sic] Alice Hatch. The cove is decorated with original plaster roses in rococo style. Not a petal was missing. The parquet floor is oak with walnut and cherry inlay and each room has a different design. There are four fireplaces in the house, no two alike. The wood here is quarter-sawn sycamore. All fireplace tiles are from Stroke-on-Trent, England. The cast iron interiors are very unusual.

Egad! This isn’t history, it’s interior design, a topic that interests me not in the least. Most of the first floor was like this, and while I’ll admit the rooms are beautiful and filled with impressive antiques, this isn’t the sort of thing I wanted to write about for this book. Fortunately the basement was a whole different experience. Here was a cornucopia of interesting historical artifacts such as brass measuring containers used by county agents to check measures by merchants, Mason jars, and a single person sauna cabinet. One exhibit was about the Willie Green Concert Band. Based in Millersburg and started in 1917, its members came from Holmes and surrounding counties. The band performed all across Ohio at patriotic events such as Memorial Day and the Fourth of July. With over fifty members, it played a variety of music that included popular and classical. Its members wore multiple uniforms, the type depending on the style of music they were asked to play.

You wouldn’t know it today, but Holmes County was once covered with forests of cherry, poplar, maple, black walnut, and white, red, and black oak trees that were cut down to fuel its considerable lumber industry. Lumbering spawned a number of mills to process the wood, which was shipped elsewhere despite the county’s mud-rutted roads. The largest of these mills was the Holmesville Lumber Company that furnished wood for Louisville bats and the PT boats used during World War II. It closed in 1961.

A robust lumber industry meant an influx of lumberjacks and mill workers who worked hard and often wanted to end their day in a saloon. Millersburg once had a row of drinking establishments. Rampant drunkenness across the United States prompted a backlash in the form of the Temperance Movement. One group trying to spread the philosophy of abstinence from alcohol were the Crusaders. In the early spring of 1874, some of Millersburg’s leading ladies, hearing about the Crusaders’ success in shutting down saloons in Hillsboro, Ohio, decided to do the same in their own town. Prayer meetings on the topic were held in churches and homes. A newspaper account reported that its local leaders were Reverend Badgely, Dr. Bigham, Mrs. John Kock, Mrs. P.B. Leadbetter, and Mrs. Rachel Albertson. Between thirty and forty people attended the early meetings.

You wouldn’t know it today, but Holmes County was once covered with forests of cherry, poplar, maple, black walnut, and white, red, and black oak trees that were cut down to fuel its considerable lumber industry. Lumbering spawned a number of mills to process the wood, which was shipped elsewhere despite the county’s mud-rutted roads. The largest of these mills was the Holmesville Lumber Company that furnished wood for Louisville bats and the PT boats used during World War II. It closed in 1961.

A robust lumber industry meant an influx of lumberjacks and mill workers who worked hard and often wanted to end their day in a saloon. Millersburg once had a row of drinking establishments. Rampant drunkenness across the United States prompted a backlash in the form of the Temperance Movement. One group trying to spread the philosophy of abstinence from alcohol were the Crusaders. In the early spring of 1874, some of Millersburg’s leading ladies, hearing about the Crusaders’ success in shutting down saloons in Hillsboro, Ohio, decided to do the same in their own town. Prayer meetings on the topic were held in churches and homes. A newspaper account reported that its local leaders were Reverend Badgely, Dr. Bigham, Mrs. John Kock, Mrs. P.B. Leadbetter, and Mrs. Rachel Albertson. Between thirty and forty people attended the early meetings.

Those who visit take a self-tour. Most large houses converted into museums that I’ve visited reserve the basement and top floor for offices and storage, so I was quite delighted to learn both were open here. I was less happy after reading the first information sign I came across on the ground floor in the parlor:

The Women’s Temperance Crusade, the first large scale organization of its type founded and run by women, formed shortly before Christmas 1873 and was launched mainly in small towns in southwestern Ohio and western New York. It soon expanded into at least to 911 communities across the nation’s states, territories, and Washington, D.C. Most of its members were concentrated in the Midwest. It succeeded in shutting down many saloons, prompting owners pushed back against the call to close down with arguments that sound familiar today. If you stop selling alcohol, jobs will be lost and tax revenues drop. Forcing saloon owners to shut their businesses down also infringed on their “personal liberty.” The National Brewers Association proposed that society should punish those who got drunk and caused problems, and not blame those who sold them the product. Some saw the Crusaders as dangerous to American society itself because women asserting political power challenged the male monopoly. This is one reason why women’s suffrage and temperance often went hand in hand.

The Millersburg-based Crusaders asked the saloon keepers to shut their establishments because of the damage it did to society. When that failed to work, they marched down Jackson Street and dropped to their knees in front of each saloon to pray, then sang a religious song. Although threatened with arrest as disturbers of the peace and, in one case, with a bucket of scalding water, they persisted. One saloonkeeper gave in, shut down, then dumped his liquor onto the street. The movement lasted for about two months until people lost interest upon the arrival the village’s annual Spring housecleaning. Although the Crusaders collapsed in 1875, from their organization arose the far more powerful and effective Women’s Christian Temperance Movement.

As I headed up the stairs to the Victorian House’s second floor, I saw four full color nineteenth century advertisements for the Sommers Piano Company. What caught my attention was that they were chromolithographs, a type of printing I’ve heard of but knew little about despite the fact I work in the printing industry. Chromolithographs are a more sophisticated type of lithography. Lithography was invented in the eighteenth century by Bavarian playwright Alois Senefelder. He wrote his scripts in reverse on limestone with greasy crayons that he covered with ink so he could readily produce copies. Involving the use of chemicals and water, at its simplest lithography is nothing more than an artist drawing on a stone surface in reverse with a greasy material.

The Millersburg-based Crusaders asked the saloon keepers to shut their establishments because of the damage it did to society. When that failed to work, they marched down Jackson Street and dropped to their knees in front of each saloon to pray, then sang a religious song. Although threatened with arrest as disturbers of the peace and, in one case, with a bucket of scalding water, they persisted. One saloonkeeper gave in, shut down, then dumped his liquor onto the street. The movement lasted for about two months until people lost interest upon the arrival the village’s annual Spring housecleaning. Although the Crusaders collapsed in 1875, from their organization arose the far more powerful and effective Women’s Christian Temperance Movement.

As I headed up the stairs to the Victorian House’s second floor, I saw four full color nineteenth century advertisements for the Sommers Piano Company. What caught my attention was that they were chromolithographs, a type of printing I’ve heard of but knew little about despite the fact I work in the printing industry. Chromolithographs are a more sophisticated type of lithography. Lithography was invented in the eighteenth century by Bavarian playwright Alois Senefelder. He wrote his scripts in reverse on limestone with greasy crayons that he covered with ink so he could readily produce copies. Involving the use of chemicals and water, at its simplest lithography is nothing more than an artist drawing on a stone surface in reverse with a greasy material.

Chromolithography, which became popular after the Civil War, uses multiple stones to create a single image. Each color has its own stone. If, for example, you have an image with fifteen colors, fifteen stones would will be used to produce it. It took up to twenty stones to produce the aforementioned ads hanging on the walls of the staircase. Chromolithographs often reproduced works of art so the average American could possess a quality reproduction of a painting at an affordable price. Books with inserted color pages printed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were often chromolithographs.

Also hanging on a wall in the museum is an excellent painting of three-year-old Carlotta Van Evera done by Ohio artist Silas Uhl. The accompanying information sign read in part that fifty-one “of his paintings are on the inventory of American paintings at the Smithsonian Institute.” This is a bit is misleading because it implies the Smithsonian possesses all those works. Curious as to which of Uhl’s works it possessed, I contacted it and asked. According to Alexandra Reigle, a reference librarian at the Smithsonian American Art Museum/National Portrait Gallery Library, Uhl’s paintings appear on the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s “Inventories of American Painting and Sculpture” and the National Portrait Gallery’s “Catalogue of American Portraits,” but the Smithsonian only owns two of his paintings, one of which is a portrait of Lewis Augustus Groff that hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

Also hanging on a wall in the museum is an excellent painting of three-year-old Carlotta Van Evera done by Ohio artist Silas Uhl. The accompanying information sign read in part that fifty-one “of his paintings are on the inventory of American paintings at the Smithsonian Institute.” This is a bit is misleading because it implies the Smithsonian possesses all those works. Curious as to which of Uhl’s works it possessed, I contacted it and asked. According to Alexandra Reigle, a reference librarian at the Smithsonian American Art Museum/National Portrait Gallery Library, Uhl’s paintings appear on the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s “Inventories of American Painting and Sculpture” and the National Portrait Gallery’s “Catalogue of American Portraits,” but the Smithsonian only owns two of his paintings, one of which is a portrait of Lewis Augustus Groff that hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

That a Uhl painting hangs in a Millersburg museum is not surprising. He was born near this village on June 20, 1841, and grew up in Holmes County. When the Civil War broke out, he joined the Union Army. He spent most of the war in West Virginia. Upon its conclusion, he went to Cleveland to study medicine while simultaneously taking art lessons from Alfred A. Hart. In 1868 Uhl chose art over medicine and opened a studio in Springfield as a portrait artist. He also taught painting and drawing. In 1873 he married Martha Phillips and eight years later the couple, accompanied by their four-year-old son Jerome Phillips, boarded the steamer City of Charleston bound for Europe.

In Paris he studied under several Parisian artists who no one but art historians have ever heard of, and in 1885 was accepted to the prestigious art exhibit known as the Salon. Upon his return to Springfield, he announced his intention to relocate to New York City where better commissions that paid his worth could be had. During his career he painted the portraits of Presidents Ulysses S. Grant, James A. Garfield, Grover Cleveland, and Benjamin Harrison. Although a superb artist, after his death on April 12, 1916, art historians have mostly ignored him. I speculate this is because his realistic paintings, good as they are, are unremarkable when compared to the innovative works of contemporaries such as Claude Monet, Gustav Klimt, and Vincent van Gogh.

In Paris he studied under several Parisian artists who no one but art historians have ever heard of, and in 1885 was accepted to the prestigious art exhibit known as the Salon. Upon his return to Springfield, he announced his intention to relocate to New York City where better commissions that paid his worth could be had. During his career he painted the portraits of Presidents Ulysses S. Grant, James A. Garfield, Grover Cleveland, and Benjamin Harrison. Although a superb artist, after his death on April 12, 1916, art historians have mostly ignored him. I speculate this is because his realistic paintings, good as they are, are unremarkable when compared to the innovative works of contemporaries such as Claude Monet, Gustav Klimt, and Vincent van Gogh.

The Victorian House’s top floor consists of a number of bedrooms and an ornate ballroom. One of bedrooms was converted into a doctor’s office in which there is a cabinet filled with forty-eight bottles from Millersburg’s now shuttered Hoffman’s Drugstore. I knew what a few items were for such as boric acid, but for the most part had never heard of any of them. So I chose several—curcuma longa, cassia buds, emery, ulmus, and sanguis—and looked them up in a couple of nineteenth dispensary books to figure out what pharmacists used them for.

Curcuma longa is a tuberous root from the East Indies that, when consumed, makes one’s urine dark yellow. It was used to treat liver diseases, jaundice, emaciation, dropsy (the accumulation of excessive fluid such as one sees in congestive heart failure) and fevers. The British stopped using it for these treatments around 1825, instead employing it as a coloring dye. Cassia buds come from the cassia tree from the East Indies whose bark is a cheap substitute for cinnamon. This is what most of us eat today. It was believed cassia buds prevented heart disease, fought diabetes, and served as an antitoxin. Lycopodium is a moss that showed up in most pharmacies as a pale yellow powder. It was used as an ingredient in pill making and was thought to treat epilepsy, rheumatism, and problems with the kidneys and heart. Its use for these ailments was discredited by 1885.

Ulmus fulva came from the inner bark of the elm tree. It was used to treat diarrhea, dysentery, and problems with urinary passages. In the nineteenth century source I consulted, there was one recorded case that a boy of fifteen eating this died, but an autopsy revealed he had consumed the bark raw and it was probably that rather than any poisonous properties that killed him. There were two recorded cases where the chewing and swallowing of the bark resulted in the removal of a tapeworm.

Emery is an exceptionally hard mineral whose powder can wear down anything but a diamond. It was used to polish hard stones and metals and was clearly sold by the pharmacy for purposes other than personal consumption. There are two kinds of sanguis. One is dried bull’s blood. It seems more likely most pharmacies would have had sanguis dragonis, or dragon’s blood, which is a resin from a plant found in the Maluku Islands, Thailand, and other places in that region of the world. It was once used to reduce bodily fluids such as blood or mucus, but by 1885 its was primarily an ingredient in paint and varnish.

One of the rooms on the house’s top floor belonged to the maid. It was sparsely decorated because one didn’t want one’s servant to get above her station. Until the advent of modern technologies such as electric lights, washing machines, dryers, dishwashers, and so forth, upper class families in the United States usually required an army of servants to do the drudgery work so as to give the family leisure time. Some middle class families also employed servants.

Curcuma longa is a tuberous root from the East Indies that, when consumed, makes one’s urine dark yellow. It was used to treat liver diseases, jaundice, emaciation, dropsy (the accumulation of excessive fluid such as one sees in congestive heart failure) and fevers. The British stopped using it for these treatments around 1825, instead employing it as a coloring dye. Cassia buds come from the cassia tree from the East Indies whose bark is a cheap substitute for cinnamon. This is what most of us eat today. It was believed cassia buds prevented heart disease, fought diabetes, and served as an antitoxin. Lycopodium is a moss that showed up in most pharmacies as a pale yellow powder. It was used as an ingredient in pill making and was thought to treat epilepsy, rheumatism, and problems with the kidneys and heart. Its use for these ailments was discredited by 1885.

Ulmus fulva came from the inner bark of the elm tree. It was used to treat diarrhea, dysentery, and problems with urinary passages. In the nineteenth century source I consulted, there was one recorded case that a boy of fifteen eating this died, but an autopsy revealed he had consumed the bark raw and it was probably that rather than any poisonous properties that killed him. There were two recorded cases where the chewing and swallowing of the bark resulted in the removal of a tapeworm.

Emery is an exceptionally hard mineral whose powder can wear down anything but a diamond. It was used to polish hard stones and metals and was clearly sold by the pharmacy for purposes other than personal consumption. There are two kinds of sanguis. One is dried bull’s blood. It seems more likely most pharmacies would have had sanguis dragonis, or dragon’s blood, which is a resin from a plant found in the Maluku Islands, Thailand, and other places in that region of the world. It was once used to reduce bodily fluids such as blood or mucus, but by 1885 its was primarily an ingredient in paint and varnish.

One of the rooms on the house’s top floor belonged to the maid. It was sparsely decorated because one didn’t want one’s servant to get above her station. Until the advent of modern technologies such as electric lights, washing machines, dryers, dishwashers, and so forth, upper class families in the United States usually required an army of servants to do the drudgery work so as to give the family leisure time. Some middle class families also employed servants.

The museum’s information sign on the topic of servants concluded, “For the most part, these domestic workers had an appreciation for their work, with the opportunity to live in an upper class home and have job security.” Although a bit too sweeping a statement to be accurate in all cases, it is true that servants who worked in rural houses such as the one the Brightmans had were paid better wages than what they would have earned in a large city such as Cleveland. The paradox here is that while rural servants made more, they had far less places in which to spend their wages.

In the latter part of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, if you wanted to find houses where an army of servants worked, you went to see Millionaire’s Row’s mansions on Euclid Avenue in Cleveland. The family occupied the center of the house and the servants the wings. The latter cooked, cleaned, laundered, and, when their long day finally ended, slept. The wings were purposely constructed using inferior materials and built with less craftsmanship because servants didn’t need luxury around them. They had to share baths and had their own plain, functional back staircase that contrasted with the decorative main one used by the family. Mansions were better to work in because they often had luxuries such as central heating, flush toilets, and electric.

People had a number of reasons to enter domestic service in the United States. For unskilled laborers it was an opportunity to learn a trade. For immigrants off the boat, it meant a steady wage as well as room and board. Servants had their own social status and pecking order. At the top of that hierarchy was the housekeeper, exceeded in rank only in the rare home that had a man who served exclusively as a butler. Next came the cook who, in addition to preparing meals, had to keep track of cooking expenses, oversee the kitchen staff, and be good at time management. Housekeepers and cooks achieved their ranks only after years of service and experience. Personal maids came next. Those at this rank needed to be able to sew, groom, and deal with wardrobe issues.

At the very bottom of the servant rung were kitchen and scullery maids. Unlike the housekeeper and cook, they rarely if ever interacted with the family, instead taking their orders from higher ranking servants. The next step up would be assistant cook, maids-of-all-work, and parlor maids. The highest ranking maid was the aforementioned personal one. The laundress was independent from the hierarchy and often lived outside the home. She usually came once a week. Few homes had a fulltime laundress, and as laundry businesses began to populate Cleveland, the need to hire a specific person to do this work disappeared.

In England servants usually came from the lower classes, and knowing their station in society after centuries of a strict social order, they rarely showed signs of open rebellion against those considered their betters. American servants weren’t so docile and rebelled where they could. Employers dreaded having servants indicate they were quitting by going through the front door and slamming it behind them. This was known as the “wooden damn.” White servants resented being called by that name because of its negative connotations associated with serfdom, indentured servitude, and especially slavery. In time even non-white servants resented this appellation, forcing employers to adopt euphemistic terms such as “the help.”🕜

In the latter part of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, if you wanted to find houses where an army of servants worked, you went to see Millionaire’s Row’s mansions on Euclid Avenue in Cleveland. The family occupied the center of the house and the servants the wings. The latter cooked, cleaned, laundered, and, when their long day finally ended, slept. The wings were purposely constructed using inferior materials and built with less craftsmanship because servants didn’t need luxury around them. They had to share baths and had their own plain, functional back staircase that contrasted with the decorative main one used by the family. Mansions were better to work in because they often had luxuries such as central heating, flush toilets, and electric.

People had a number of reasons to enter domestic service in the United States. For unskilled laborers it was an opportunity to learn a trade. For immigrants off the boat, it meant a steady wage as well as room and board. Servants had their own social status and pecking order. At the top of that hierarchy was the housekeeper, exceeded in rank only in the rare home that had a man who served exclusively as a butler. Next came the cook who, in addition to preparing meals, had to keep track of cooking expenses, oversee the kitchen staff, and be good at time management. Housekeepers and cooks achieved their ranks only after years of service and experience. Personal maids came next. Those at this rank needed to be able to sew, groom, and deal with wardrobe issues.

At the very bottom of the servant rung were kitchen and scullery maids. Unlike the housekeeper and cook, they rarely if ever interacted with the family, instead taking their orders from higher ranking servants. The next step up would be assistant cook, maids-of-all-work, and parlor maids. The highest ranking maid was the aforementioned personal one. The laundress was independent from the hierarchy and often lived outside the home. She usually came once a week. Few homes had a fulltime laundress, and as laundry businesses began to populate Cleveland, the need to hire a specific person to do this work disappeared.

In England servants usually came from the lower classes, and knowing their station in society after centuries of a strict social order, they rarely showed signs of open rebellion against those considered their betters. American servants weren’t so docile and rebelled where they could. Employers dreaded having servants indicate they were quitting by going through the front door and slamming it behind them. This was known as the “wooden damn.” White servants resented being called by that name because of its negative connotations associated with serfdom, indentured servitude, and especially slavery. In time even non-white servants resented this appellation, forcing employers to adopt euphemistic terms such as “the help.”🕜

Victorian House

This portrait of Richard P. White is by Silas Ulh. One of his paintings (not this one) can be found on one of the museum's walls.

Steam Bath

Bottles from Hoffman's Drug Store

Maid's Room

Ball Room

The Teisher family bear is in the house's lawn.

No self-respecting historical museum is without a least one piano or organ.

Barber Shop