Warren G. Harding Presidential Sites

Museum

Warren G. Harding's House

Front porch from which Warren G. Harding gave most of his speeches while running for president.

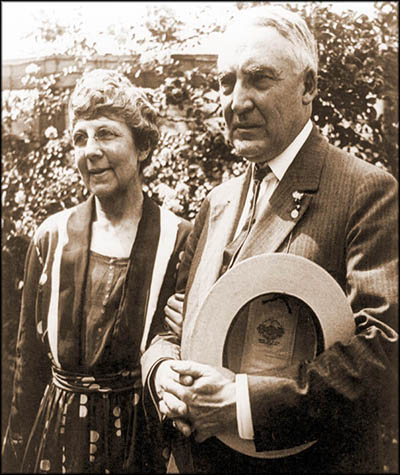

Florence and Warren Harding.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

President Warren G. Harding is probably best remembered for three things: using “A Return to Normalcy” as a campaign slogan, corruption during his administration, and dying while in office. Many historians consider him one of the worst American presidents of all time. Yet shortly after his death, Republican supporters formed the Harding Memorial Association to which Harding’s widow willed her and her husband’s house so it could be made into a museum. She died the year after Warren. The Harding museum temporarily closed its doors to the public in 2017 so it could be restored to what it looked like in 1920. Beside the house, construction of an accompanying museum/library began in 2019. The result is now known as the Warren G. Harding Presidential Sites.

When I reached Marion to see this updated museum, I discovered something anyone visiting this small city will want to know: it’s filled with an overabundance of one way streets. It took me little time to turn the wrong way down one of them, which I quickly realized when I saw traffic coming toward me. About half a block later, I turned onto another street, only to find it, too, was one way and I was still going the wrong direction! I turned into a bank’s parking lot and reversed coarse. It was in the nick of time. About a block later I passed a police car.

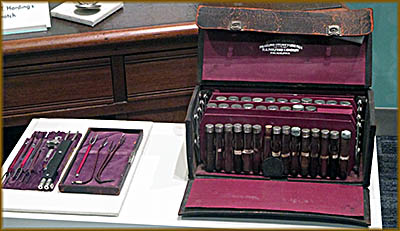

Harding was born near Blooming Grove, Ohio, on November 2, 1865. His parents moved the family to Caledonia, Ohio, in 1871, where his mother, Phoebe, and father, George, practiced homeopathic medicine. George had previously farmed and been a teacher before becoming a physician. Phoebe, a midwife, focused on treating women and children. According to an information sign in the museum, “homeopathic medicine treats the whole person—body, mind and spirit—with the smallest dose of medication needed to trigger the body to heal itself.” The concept came from German physician Samuel Hahnemann. This form of medicine failed to help two of the couple’s children, Carolyn and George, who both died on November 10, 1878, of yellow jaundice. A look at what a homeopathic a medicine bag contained in those days shows why. Substances such as mercury and arsenic aren’t conducive to good health.

When I reached Marion to see this updated museum, I discovered something anyone visiting this small city will want to know: it’s filled with an overabundance of one way streets. It took me little time to turn the wrong way down one of them, which I quickly realized when I saw traffic coming toward me. About half a block later, I turned onto another street, only to find it, too, was one way and I was still going the wrong direction! I turned into a bank’s parking lot and reversed coarse. It was in the nick of time. About a block later I passed a police car.

Harding was born near Blooming Grove, Ohio, on November 2, 1865. His parents moved the family to Caledonia, Ohio, in 1871, where his mother, Phoebe, and father, George, practiced homeopathic medicine. George had previously farmed and been a teacher before becoming a physician. Phoebe, a midwife, focused on treating women and children. According to an information sign in the museum, “homeopathic medicine treats the whole person—body, mind and spirit—with the smallest dose of medication needed to trigger the body to heal itself.” The concept came from German physician Samuel Hahnemann. This form of medicine failed to help two of the couple’s children, Carolyn and George, who both died on November 10, 1878, of yellow jaundice. A look at what a homeopathic a medicine bag contained in those days shows why. Substances such as mercury and arsenic aren’t conducive to good health.

After graduating from Ohio Central College in Iberia, Ohio (now defunct), Warren moved with his parents to Marion. It was while here he met Florence Mabel Kling, the woman he’d marry in 1891. Born on August 15, 1860, in Marion, her parents were Amos and Louisa Bouton Kling. Amos was the richest man in town and gave his daughter all a child could desire. She learned about bookkeeping from working at the hardware store he owned. She was given horses and became an excellent rider. After high school she attended Miss Nourse’s School for Young Ladies, now the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music, where she trained as a classical pianist.

At the age of nineteen, she was impregnated by her boyfriend, Henry Atherton DeWolfe, who her father saw as a good-for-nothing. The resulting birth gave her and Henry a son, Marshall Eugene DeWolfe, who was born on September 22, 1880. Florence and Henry had a common law marriage, meaning that they lived as man and wife but lacked a marriage certificate. Amos Kling’s assessment of Henry had been right. An alcoholic, he disappeared for weeks on end. He and Florence divorced in 1884. Florence returned home only to have her father forcibly take custody of Marshall—which he never relinquished—and to tell his daughter he wouldn’t support her. She’d have to make her own money, which she did mainly by giving piano lessons.

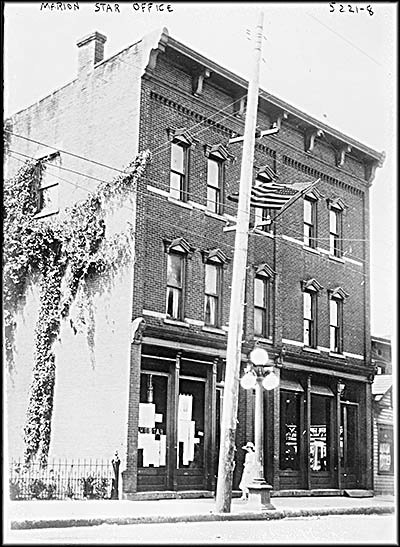

After college, Warren’s prospects were uncertain. He dabbled in a number of jobs including law and insurance, but none them turned into a career. Then one of the local papers, the Marion Star, came up for sale at a sheriff’s auction, so he and two friends raised some money and bought it for $300. Harding was just nineteen. Turning a failing newspaper into a profitable one is no easy task and for the first few years, Harding struggled to keep it afloat. At one point the bank repossessed the paper’s hand-cranked press, so he to purchase on credit a used cylinder press. Although more efficient, it had reliability issues.

At the age of nineteen, she was impregnated by her boyfriend, Henry Atherton DeWolfe, who her father saw as a good-for-nothing. The resulting birth gave her and Henry a son, Marshall Eugene DeWolfe, who was born on September 22, 1880. Florence and Henry had a common law marriage, meaning that they lived as man and wife but lacked a marriage certificate. Amos Kling’s assessment of Henry had been right. An alcoholic, he disappeared for weeks on end. He and Florence divorced in 1884. Florence returned home only to have her father forcibly take custody of Marshall—which he never relinquished—and to tell his daughter he wouldn’t support her. She’d have to make her own money, which she did mainly by giving piano lessons.

After college, Warren’s prospects were uncertain. He dabbled in a number of jobs including law and insurance, but none them turned into a career. Then one of the local papers, the Marion Star, came up for sale at a sheriff’s auction, so he and two friends raised some money and bought it for $300. Harding was just nineteen. Turning a failing newspaper into a profitable one is no easy task and for the first few years, Harding struggled to keep it afloat. At one point the bank repossessed the paper’s hand-cranked press, so he to purchase on credit a used cylinder press. Although more efficient, it had reliability issues.

The Marion Star first showed a profit in the mid-1890s, allowed Harding to invest in a linotype machine in 1895. He started a weekly newspaper to serve Ohio’s rural population, and hired more people so he had time for other pursuits such as politics. The Star moved twice during Harding’s ownership, the last being in a building bought in 1889 by he and his father. It no longer stands. As of this writing, the Marion Star is still in business. After his marriage to Florence in 1891, she took running the paper’s finances, one of the biggest reasons for its success.

As Warren and Florence courted, marriage between them wasn’t a certain thing. Florence’s father threatened to kill Harding if he married his daughter in the false belief that Harding had some African blood in his ancestry. When they did get engaged, Harding needed a home for them. Construction on a new house began in the summer of 1890. Warren and Florence married in its reception hall on July 8, 1891. Her father boycotted the wedding and refused to speak to her for the next seven years. Despite being forbidden by Amos to do it, Florence’s mother slipped into the wedding, watched her daughter marry, and slipped out. Florence didn’t this until after her mother’s passing.

Many times after the death of a famous person, possessions either go to relatives or are sold off. Houses leave the family and it isn’t until a century or more later that they become museums. Because the Harding house was slated to become a museum even before Florence died, everything from its furniture to rugs to the toaster on the dining room table are original. To see the house you must have a guide. You’re also not aren’t allowed to take photos of its interior, so none accompany this travel log. A few can be found online here.

As Warren and Florence courted, marriage between them wasn’t a certain thing. Florence’s father threatened to kill Harding if he married his daughter in the false belief that Harding had some African blood in his ancestry. When they did get engaged, Harding needed a home for them. Construction on a new house began in the summer of 1890. Warren and Florence married in its reception hall on July 8, 1891. Her father boycotted the wedding and refused to speak to her for the next seven years. Despite being forbidden by Amos to do it, Florence’s mother slipped into the wedding, watched her daughter marry, and slipped out. Florence didn’t this until after her mother’s passing.

Many times after the death of a famous person, possessions either go to relatives or are sold off. Houses leave the family and it isn’t until a century or more later that they become museums. Because the Harding house was slated to become a museum even before Florence died, everything from its furniture to rugs to the toaster on the dining room table are original. To see the house you must have a guide. You’re also not aren’t allowed to take photos of its interior, so none accompany this travel log. A few can be found online here.

The Hardings were great animal lovers. After an artist was commissioned to paint a portrait of Warren, Florence asked him to do one of their beloved Boston terrier, Edgewood Hub. The painting of Warren went into the basement. Hub’s was placed above the fireplace in the library. Florence must have really loved that dog to leave it in there because it’s awful. During their married years, the Hardings had several other dogs as well as Florence’s horse, Billy, who drove her carriage to the newspaper office in exchange for a lump of sugar.

Contemporaries described Harding as affable, an excellent speaker, and that he looked presidential. Detractors said he was a slob, a drunk, and chronic gambler. When he decided to get into politics, he allied himself with the conservative wing of the Republican Party. It had the philosophy that government ought not interfere with Big Business. The progressive wing of the party, in contrast, felt government ought to protect the average person from Big Business. Harding didn’t always keep to the conservative wing’s policies, but when it came to union busting, he was an enthusiast.

The first office he sought was for county auditor in 1892. In this he failed. But with the backing of U.S. Senator Joseph B. Foraker, he was elected a state senator in 1899. After two terms of this office, he sought the Republican nomination for governor, ultimately settling for running as lieutenant governor with Myron T. Herrick at the top of the ticket. They won but lost a bid for reelection. In 1910, Harding ran for governor in his own right and lost. In 1914, he ran for and was elected one of Ohio’s U.S. Senators.

Contemporaries described Harding as affable, an excellent speaker, and that he looked presidential. Detractors said he was a slob, a drunk, and chronic gambler. When he decided to get into politics, he allied himself with the conservative wing of the Republican Party. It had the philosophy that government ought not interfere with Big Business. The progressive wing of the party, in contrast, felt government ought to protect the average person from Big Business. Harding didn’t always keep to the conservative wing’s policies, but when it came to union busting, he was an enthusiast.

The first office he sought was for county auditor in 1892. In this he failed. But with the backing of U.S. Senator Joseph B. Foraker, he was elected a state senator in 1899. After two terms of this office, he sought the Republican nomination for governor, ultimately settling for running as lieutenant governor with Myron T. Herrick at the top of the ticket. They won but lost a bid for reelection. In 1910, Harding ran for governor in his own right and lost. In 1914, he ran for and was elected one of Ohio’s U.S. Senators.

Warren had an eye for pretty ladies. He had a long time affair with his friend’s wife, Carry Phillips, that went sour during World War I. An ardent supporter of Germany, Phillips attempted to blackmail Senator Harding into voting against going to war with Germany. She was at this point under surveillance by the U.S. Secret Service. When Harding ran for president in 1920, the Republican National Committee gave her and her husband $20,000, a promise of monthly payments, and a long trip to Japan if she kept quiet. The couple took the deal.

In late 1919, a prominent member of the Ohio Republican Party, Harry M. Daugherty of Washington Court House, put forth Harding as a possible presidential candidate. National leaders dismissed this. But during the convention no consensus candidate could be found, and on the tenth ballot Harding became the party’s nominee. He decided that instead of barnstorming across the nation, he’d campaign from the front porch of his house. Other presidents before him had done so with success, so it wasn’t a bad idea.

The Harding house’s original porch wasn’t an especially large affair. It was during Warren’s time as lieutenant governor that it was discovered that too many people standing on it at once caused it to sag, so it was replaced with a larger, sturdier one. Doing a front porch campaign called for a few modifications. Concrete was poured on top of the porch floor and tiles placed upon that. Done too quickly, the tiles began cracking, a state they are still in today. Harding was informed a hoard of people listening to his speeches in his front yard would kill his grass, and when it rained, it would turn to mud, so it was covered with gravel.

Needing a place for the press to work, Harding ordered a premade house kit—no one at the museum knows if it came from Sears or not—and this was put went up in two days. This small house, or really cottage, still stands today and in it one can find rotating exhibits. The one on display when I visited was about the history of women’s suffrage in Ohio, something Harding supported and voted for. No artifacts were to be found here, just a series of information signs.

In late 1919, a prominent member of the Ohio Republican Party, Harry M. Daugherty of Washington Court House, put forth Harding as a possible presidential candidate. National leaders dismissed this. But during the convention no consensus candidate could be found, and on the tenth ballot Harding became the party’s nominee. He decided that instead of barnstorming across the nation, he’d campaign from the front porch of his house. Other presidents before him had done so with success, so it wasn’t a bad idea.

The Harding house’s original porch wasn’t an especially large affair. It was during Warren’s time as lieutenant governor that it was discovered that too many people standing on it at once caused it to sag, so it was replaced with a larger, sturdier one. Doing a front porch campaign called for a few modifications. Concrete was poured on top of the porch floor and tiles placed upon that. Done too quickly, the tiles began cracking, a state they are still in today. Harding was informed a hoard of people listening to his speeches in his front yard would kill his grass, and when it rained, it would turn to mud, so it was covered with gravel.

Needing a place for the press to work, Harding ordered a premade house kit—no one at the museum knows if it came from Sears or not—and this was put went up in two days. This small house, or really cottage, still stands today and in it one can find rotating exhibits. The one on display when I visited was about the history of women’s suffrage in Ohio, something Harding supported and voted for. No artifacts were to be found here, just a series of information signs.

While well done, I didn’t learn a whole lot from it. The best part was the mini-biographies of women suffragettes who worked in or came from Ohio. Victoria Woodhull, born in Ohio’s Licking County, opened a Wall Street brokerage in New York City, became a newspaper publisher, and in 1872 was the first woman to run for president of the United States. Viola D. Romans was both a suffragette and a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. In 1932, she became the first woman to be elected as a representative in the Ohio House for her district. Georgia Hopley of Bucyrus was appointed by Harding as the nation’s first Prohibition agent, although she only did publicity.

Harding’s presidential campaign is considered by some the first modern one because he used new technologies and modern marketing techniques to get his message out, such as recording speeches on vinyl records. Although microphones existed and he used them elsewhere, he chose not to use one when speaking from his front porch because he didn’t want it to come between him and the crowd. His campaign slogans were a “A Return to Normalcy” and “America First.” “Normalcy” wasn’t coined by Harding—it first appeared in print in 1857—but it was a useful word for what he was promised. Harding pledged to end the remnants of the federal government’s controls over industry and the economy initiated during World War I. “America First” signaled, among other things, that he would crack down on the number of immigrants allowed in the United States from southern and eastern Europe.

Harding’s presidential campaign is considered by some the first modern one because he used new technologies and modern marketing techniques to get his message out, such as recording speeches on vinyl records. Although microphones existed and he used them elsewhere, he chose not to use one when speaking from his front porch because he didn’t want it to come between him and the crowd. His campaign slogans were a “A Return to Normalcy” and “America First.” “Normalcy” wasn’t coined by Harding—it first appeared in print in 1857—but it was a useful word for what he was promised. Harding pledged to end the remnants of the federal government’s controls over industry and the economy initiated during World War I. “America First” signaled, among other things, that he would crack down on the number of immigrants allowed in the United States from southern and eastern Europe.

Harding’s strategy worked. He won 26.17% more than his opponent in the popular vote. Despite being a tool of the Republican Party’s conservative wing, he did support some progressive policies. Realizing just how bad American roads were, he signed the Federal Highway Act in 1921 to encourage the construction of improved roads. He also felt the aviation industry needed some regulation to keep it safe, and after his death, Congress passed the Aviation Act to do implement this. At this time infant mortality was on the rise, so Harding signed the Infancy Protection Act that distributed federal funds for educating people about prenatal health and the proper care of infants. It was a success. Despite his opposition to unions and his coddling to the needs of Big Business, he did persuade the nation’s largest steel producers to limit their workdays to eight hours.

The biggest shortcoming of the Harding Presidential Sites is it that it has very little about the numerous personal and political scandals that erupted during his presidency. Not a word, for example, did I find about Nan Britton. Obsessed with Harding, at the age of twenty she wrote to him asking for a job. Unable to resist a pretty blond, he arranged a clerkship for her at U.S. Steel in Washington, D.C. Their affair, often consummated in closets, produced a daughter, Elizabeth Ann Christian. She was born on October 22, 1919. (Why Harding and Florence never produced a child may have to do with that fact that Florence suffered from chronic kidney disease, which can result in infertility.)

To his credit, Harding supported his daughter, often sending funds to his lover via the Secret Service. After his death, Nan sued to get a trust fund for Elizabeth that failed. To raise money, she wrote the salacious book The President's Daughter. This came out in 1928 and sold over 75,000 copies. When asked about her during the house tour, our guide said this book isn’t very accurate and may have been ghostwritten. Many disbelieved Harding fathered Nan’s child and even claimed he was infertile. A 2015 DNA test proved that he was indeed the father.

Upon occupying the Oval Office, Harding made some excellent cabinet appoints such as Charles Evans Hughes as secretary of state, Herbert Hoover as secretary of commerce, and Henry C. Wallace as secretary of war. Harding also made some spectacularly bad selections. The man he chose to run the Veterans Bureau, Charles R. Forbes, embezzled $250 million. This money was supposed to used for the construction of veterans’ hospitals and buildings. Forbes was allowed to resign and go abroad.

Harding appointed his campaign manager, Harry Daugherty, as attorney general. Some of Daugherty’s friends from Washington Court House set up a headquarters on K Street from which they took bribes, sold government appointments, arranged for pardons and paroles from the Justice Department, and did many other patently illegal things to make money. Dubbed the “Ohio Gang,” they also used the house as a brothel and speakeasy. Daugherty’s right-hand man and housekeeper, Jesse Smith, committed suicide when this scandal came to light. Daugherty was tried but hung juries left him a free man. His refusal to answer questions while testifying before Congress left his reputation ruined.

The biggest shortcoming of the Harding Presidential Sites is it that it has very little about the numerous personal and political scandals that erupted during his presidency. Not a word, for example, did I find about Nan Britton. Obsessed with Harding, at the age of twenty she wrote to him asking for a job. Unable to resist a pretty blond, he arranged a clerkship for her at U.S. Steel in Washington, D.C. Their affair, often consummated in closets, produced a daughter, Elizabeth Ann Christian. She was born on October 22, 1919. (Why Harding and Florence never produced a child may have to do with that fact that Florence suffered from chronic kidney disease, which can result in infertility.)

To his credit, Harding supported his daughter, often sending funds to his lover via the Secret Service. After his death, Nan sued to get a trust fund for Elizabeth that failed. To raise money, she wrote the salacious book The President's Daughter. This came out in 1928 and sold over 75,000 copies. When asked about her during the house tour, our guide said this book isn’t very accurate and may have been ghostwritten. Many disbelieved Harding fathered Nan’s child and even claimed he was infertile. A 2015 DNA test proved that he was indeed the father.

Upon occupying the Oval Office, Harding made some excellent cabinet appoints such as Charles Evans Hughes as secretary of state, Herbert Hoover as secretary of commerce, and Henry C. Wallace as secretary of war. Harding also made some spectacularly bad selections. The man he chose to run the Veterans Bureau, Charles R. Forbes, embezzled $250 million. This money was supposed to used for the construction of veterans’ hospitals and buildings. Forbes was allowed to resign and go abroad.

Harding appointed his campaign manager, Harry Daugherty, as attorney general. Some of Daugherty’s friends from Washington Court House set up a headquarters on K Street from which they took bribes, sold government appointments, arranged for pardons and paroles from the Justice Department, and did many other patently illegal things to make money. Dubbed the “Ohio Gang,” they also used the house as a brothel and speakeasy. Daugherty’s right-hand man and housekeeper, Jesse Smith, committed suicide when this scandal came to light. Daugherty was tried but hung juries left him a free man. His refusal to answer questions while testifying before Congress left his reputation ruined.

These incidents paled in comparison to what Harding’s secretary of the interior, Albert Fall, was up to. In 1921, Harding transferred control of the Navy’s oil reserves at Teapot Dome, Wyoming, and Elk Hills, California, to the department of the interior, a move the Supreme Court later ruled he didn’t have the authority to do. Now in control these assets, Fall secretly sold leases for them in exchange for $100,000 in a loan he never had to repay and $200,000 in bonds—a value of just over $4.8. million today. Drilling rights for Teapot Dome went to the Mammoth Oil Company, and the rights for Elk Hills to Pan American Petroleum. Upon learning of this, Congress ordered Harding to revoke the leases, which he did. Fall went to prison for his actions in 1931.

Harding likely knew nothing about any of this corruption until it came to light by the investigations of others, but it nonetheless took a heavy toll on him. Disgusted, on June 20, 1923, he and a party of sixty-five headed to Alaska as part of a West Coast tour. In Seattle he nearly collapsed while giving a speech. Diagnosed with food poisoning, he headed to San Francisco. By the time he arrived, he was re-diagnosed with having had a heart attack and that he was suffering from bronchial pneumonia. On August 2, 1923, a cerebral hemorrhage did him in. That he had a heart attack, then a stroke at the age of fifty-seven isn’t surprisingly when one learns he was an exceptionally heavy smoker.🕜

Harding likely knew nothing about any of this corruption until it came to light by the investigations of others, but it nonetheless took a heavy toll on him. Disgusted, on June 20, 1923, he and a party of sixty-five headed to Alaska as part of a West Coast tour. In Seattle he nearly collapsed while giving a speech. Diagnosed with food poisoning, he headed to San Francisco. By the time he arrived, he was re-diagnosed with having had a heart attack and that he was suffering from bronchial pneumonia. On August 2, 1923, a cerebral hemorrhage did him in. That he had a heart attack, then a stroke at the age of fifty-seven isn’t surprisingly when one learns he was an exceptionally heavy smoker.🕜

Medicine Case

Marion Star Building

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Camera used by the Marion Star.

Museum Interior

This side saddle was given to Florence Harding by her father around 1870.

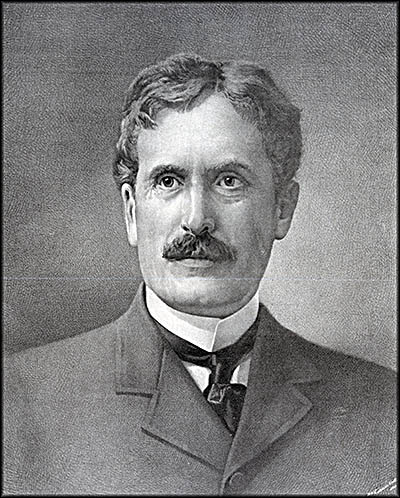

Myron T. Herrick

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Harding's Desk and Chair from His Senate Office

Harding Presidential Campaign Poster

During Harding's front porch campaign, police had to keep watch on the house. Several guardhouses like this replica were constructed to give police a refuge from the elements.